Peter the Great’s reaction to Ivan Mazepa’s geopolitical turn towards Sweden in 1708 was the plundering ofBaturyn, the capitalof the Cossack Hetmanate. The hetman’s residence moved to Hlukhiv, a town in Sumy Oblast, to bestaffed with people authorized by St. Petersburg. Central government bodies of the left-bank Ukraine, including courts, administrative and military authorities, moved to this borderline town as well.

Courts tend to be a reflection of society at all times, their archives often helping historians understand daily lifeand social deviations of the period they research. The most widespread cases settled in Ukraine’s courts of that time included conflicts over land, family, daily matters, thefts,as well as overaccusations of witchcraft or magic. In 1740, however, the new capital of the Cossack Hetmanate saw a process that startled the nation: the central court in Hlukhiv issued a death sentence and executed Pavlo Mishchenko, better known as Matsapura, one of the most cruel maniacs of the 18th century.

The casestarted with a letter the General Military Court in Hlukhiv received from the chancellery of Lubny, today’s Poltava Oblast, in the summer of 1740. The letter said that the town’s authorities were afraid to execute four criminals and asked the higherauthorityto deal with this. There was no hetman in Hlukhiv in 1740 while the Zaporizhzhian Army was commanded by the Hetman Government Command, a collegial body comprised of three Russians and three Ukrainians. The central authorities, including the General Military Chancellery and the General Court, thus had to issue the final verdict in the high-profile case. What was the administration in Lubny so afraid of?

Officially, the Lubny authorities said that they could not ensure proper guard for the prisoners as theirsecurity staff wasbusy witha harvesting campaign. Without proper security, the horrifying crimes committed by the inmates could have provoked riots in the town and led tostreet justice. A decision was takento send the convictsto Hlukhiv without delay.

Matsapura’s gang and its first crimes

Pavlo Shulzhenko was the lead villain. Better known as Matsapura, this bandit was originallyfrom Kolisnyky, a village in Pryluky region supervised by the Pryluky Garrison. Shulzhenko did not have a family and often wondered to other villages looking for work. A file from the 1740 case described Pavlo’s appearance: “tall, with light brown hair, grey eyes, long nose, shaved beard, wide shouldered, with traces of flogging.”

The oldest member of the gang was Mykhailo Mishchenko otherwise known as The Great. He was about 40 years old. Originally from the village of Rudivka under Pryluky Garrison, he was a widower.

The gang enrolled two young men – Yakym Pivnenko, 20, and Andriy Pashchenko, 15. All four came from broken families and had no stable income, so they were forced to work for other landowners. Pivnenko was an orphan, while Matsapura, Mishchenko and Pashchenko missed one of the parents.

Pavlo Shulzhenko-Matsapura, the gang’s leader and mastermind, began his criminal career with small theft and horsetheft. He served his first term in the Pryluky Garrison jailafter reaching for the property of flag sergeant Domoratsky, a low-level command position in the Cossack military hierarchy. That’s where Matsapura was flogged and released after the horses he had stolen were found. He then moved to the hamlet of Kantakuzivka in Pereyaslav area and carried on with his usual horse theft and petty theft for another three years. He ended up in jail in 1738 again after stealing from Andriy Horlenko, an officer in Stasivshchyna hamlet near Pryluky: Matsapura was caught for stealing four horses from this high official and jailed at the Pryluky Garrison Jail.

Released after a year in prison, Shulzhenko returned to his usual craft while growing crueler. In August 1739, he and his companion killed horilka traders around the village of Losynivka near Nizhyn, stealing nearly one ton of the booze and hiding the bodies in the reeds.

At the end of November 1739, Matsapura was caught again and jailed at the Pryluky Prison, a usual destination for a serious criminal. But the investigators failed to prove his murders. For the theft he was assigned to some special “community work” which none of the inmates were willing to do: he became an executioner at the Pryluky Prison. Matsapura served about three months in that capacity before escaping in February 1740 to join six companions in a gang that went to plunder and steal horses around the hamlet of Romanykha. The first victims of the new gang were horilka traders: three out of ten managed to flee during one attack while seven were killed and buried in the snow.The villains then went home to hide their traces. Shulzhenko stayed in Romanykha until Easter on April 6, 1740, then moved to the village owned by Count Tolstykh near Pyriatyn. Shortly before, some new local bandits had joined his gang. Their names were eventually established thanks to the testimony of some criminals: Ivan Chornyi, Panas Piven, Ivan Kochubei and shepherd Pavlo. Four more from around Zaporizhzhia Host, including Ivan Taran, Mykhailo Makarenko, Denys Hrytsenko and Martyn Revytskyi, joined their ranks soon – possibly haidamaky, the impoverished rebels of the right-bank Ukraine. Revytskyi’s brother Vasyl also joined the gang. Unlike his colleagues, he knew how to write and read. The criminals were racketeering the locals in Tolstykh’s village using burning sticks to torture their victims.

Baturyn casemate. Modern reconstruction

Massacre at the kurgan

After the inflow of new members, the gang moved to Telepen, a Scythian kurgan, a burial mound towering over Lemeshivka, a village on the Hnyla Orzhytsia river at the intersection of Chernihiv, Poltava and Kyiv oblasts. Once the bandits settled down, they began to terrorize the surrounding area. First, they killed three merchants who stayed for the night near the village of Mokiyivka. Two others were luckier: they paid for their lives with virtually all the merchandise, including about 1,700 liters of horilka and as many goods. The bandits sold horilka through trusted pubs and stolen horses at the markets. They hid the jewelry and spent part of the money on booze.

Apart from that, Matsapura’s gang killed witnesses. Near the village of Biloshapky, the villains killed a shepherd who recognized their leader as they returned from one of their raids. A similar murder took place near the village of Zhurivka where they beat two shepherds to death so that they wouldn’t report on the gang’s crimes.

More was coming. Soon enough the bandits kidnapped, raped and killed a woman from Zhurivka, then three more women. At one point, they even killed a pregnant woman near the village of Andriyivka. One of the bandits, Ivan Taran, suggested using the embryo for “magic”, so he cut it out and put it in his bag to later use in a horrifying ritual. They raped and killed another woman on the way close to the Valkivka village – Ivan cut the victim’s feet and put it in his bag, too.

That sadism climaxed with a magic ritual at Telepen: each of the 16 bandits had to toss and catch the heart Ivan cut out from the embryo. He said that whoever managed to do that would avoid any punishment for their crimes. The gang completed the bloody ritual and ate the heart and the body of the unborn girl.

The next day the young members of the gang, Pivnenko and Pashchenko, caught a woman and cut her breasts out – she bled to death in an attempt to escape. A few days later, a girl was caught near Telepen – each of the 16 sadists took part in a gang rape. They then cut her feet off and buried her body. One of them admitted at an interrogation that they committed another act of cannibalism after that by eating body parts of their victims.

At the end of May, Matsapura left most of his allies at Telepen and moved to the village of Mykhailivka in Poltava Oblast to join an old acquaintance, Klym Zaporozhets. They killed two traders near Mokiyivka and stole their horilka. After that the two gangs joined forces and moved towards Lubny. As they approached Kruhlyk, a town on the way, they attacked two merchants. One escaped while the other one was murdered.

Obviously, they could not have continued these massacres for much longer. For almost three months, the villains kept the whole Poltava area terrified. Eventually, the authorities had to do something.

In May 1740, the Garrison Administration in Pyriatyn received a complaint from the residents of Smotryky, a small village in the area, reporting that a gang of bandits was terrorizing the neighborhood. The local military squadron commander Dorosh Bozhko personally hunted down and caught three of the gang, including Mishchenko, Pivnenko and Pashchenko. Ivan Kucherevskiy, the master of stables for General Treasurer Andriy Markovych, caught the gang leader, Matsapura himself, for a petty theft. They were all arrested and immediately sent from Pyriatyn to Lubny where garrison authorities conducted an investigation and delivered verdicts on July 24, 1740: for murders and cannibalism the four criminals would be executed by “pulling their ribs out with hot tongs, horse-drawing and breaking wheel.”

Given how scandalous the case was, the Lubny Chancellery soon asked higher authorities in Hlukhiv, the Hetmanate’s capital, to take over the inmates and execute the verdict. On August 3, 1740, the General Military Chancellery approved the request. The Hetmanate’s central government body took over the case and ordered a transfer of the criminals to Hlukhiv Garrison Prison.They spent August interrogating the inmates with torture and beating, while searching for the rest of the gang across all of the Cossack Hetmanate’s provinces. Three respective requests from the military chancellery and search groups of the Hetman’s cavalry guard were in vain. Eventually, the criminal cases on Matsapura from 1735 and 1738 were sent to Hlukhiv from Pryluky Military Chancellery. The investigators managed to find his one-time companions involved in those episodes.

Trial and verdicts

On September 30, 1740, the General Military Court in Hlukhiv confirmed the verdict from Lubny. The four criminals were to be executed at the Telepen Kurgan where they had committed their most hideous crimes. Soon enough, on October 4, 1740, a special assembly of the General Military Chancellery chaired by James (Jacob) Keith[1]confirmed theexecutionmeasures but changed the location – the intention was to make the execution as public and demonstrative as possible. Telepen, a burial mound outside of any city or town, was not good for this. The verdict against two youngest criminals was executed without delay: Pivnenko was executed during a fair in Pryluky on October 26, while Pashchenko faced death at Telepen the following day. Both had their legs and arms cut off, their bodies placed on wheels and limbs spiked on sticks.

Interrogations of two older villains carried on. The interrogators tortured Matsapura and Mishchenko into revealing new horrendous details of their crimes: 9 out of 16 bandits participated in cannibalistic rituals, encouraged by their companion Ivan Taran. He presented himself as magician from his time as haidamakaand told his allies that his rituals would help them avoid punishment. In fact, 12 bandits from the gang were never caught. Moreover, their leader managed to escape from the Hlukhiv prison on November 30. When his guardian fell asleep, Matsapura got out of his jail cell. He used a horse bone and a piece of wood to open his chains on the way and reached the village Oblozhky where he spent some time hiding in a barn before the villagers caught him and handed him over to the authorities.

After the investigators learned all possible details of the gang’s crimes, an order came on December 18 to prepare for execution of the two bandits. On December 22, 1740, one of the first maniacs in the nation’s history was executed in Hlukhiv. The executioner cut off Matsapura’s fingers, toes, nose and ears and spiked him. His companion, Mykhailo Mishchenko, was quartered and wheeled at another location.

Professor Mykhailo Slabchenko, a researcher of Cossac khistory, claimed that Matsapura’s execution was exceptional: it was rare in the Hetmanate that similar crimes were not punished by death on a breaking wheel.

Later, General Deputy Treasurer Jakiv Markovych wrote in his Home Protocol of another member of the cannibal gang executed in Hlukhiv. Vasyl Malchenko, a professor at the Hlukhiv Gymnasium in the early 20thcentury, specified that the sadist was burnt alive, burning metal poured into his throat. He wrote in his memoirs that the locals around the former Hetmanate capital used matsapuraas a swearword for a long time after that.

Making it into books

The horror story of maniac Matsapura had every chance to be forgotten if it had not been for Ivan Kotliarevskiy, the pioneer of modern Ukrainian literature who mentioned him in his best-known parody poem Eneyida. Kotliarevskiy used the word matsapura for Maksym Parpura, a philanthropist from Konotop who published Kotliarevskiy’s poem in St. Petersburg in 1798 without the author’s consent. Eventually, the poem became a canon of modern Ukrainian language. In the new edition of the poem 11 years later (1809), Kotliarevskiy placed Parpura in hell for “publishing something he does not own”:

A certain matsapura person

Was roasting, skewered on a spit.

Hot copper pouring over,

They crucified him on a stick.

He twisted all his soul for profits,

Sending to print what he didn’t own –

Without shame or God in mind,

Oblivious of Eighth Commandment,

He went on profiteering from others.

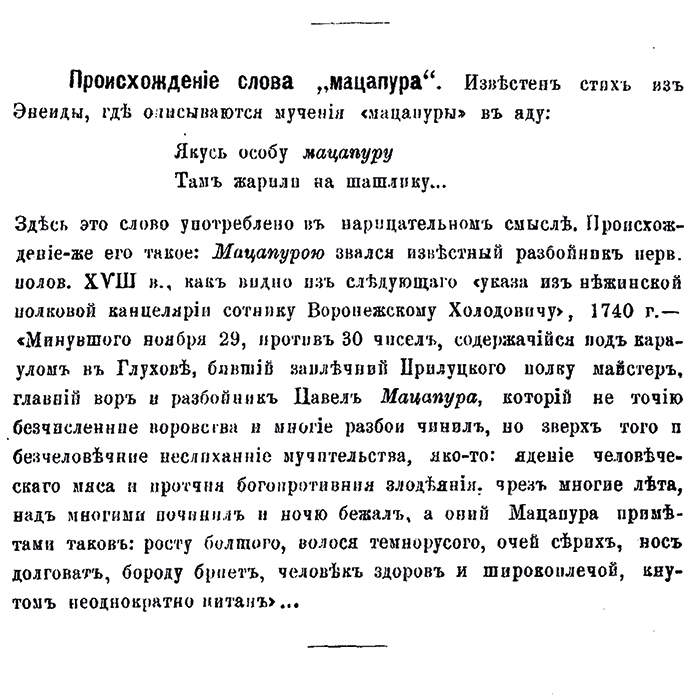

In 1901, Kyivska Starovyna, a journal of Kyiv and Ukrainian history, published a short note explaining the origin of the strange word matsapura used by Kotliarevskiy in his poem.

Etymological footprint. Kyivska Starovyna, a history and linguistics journal, describes how Pavlo Matsapura’s last name turned into a word for violent villains in the 18th century

Kharkiv historian Mykola Horban looked at the case from an academic perspective and published a historical essay titled Bandit Matsapurain 1926. As he analyzed investigation archives, he pointed to the ritual nature of the gang’s crimes, the dehumanization of impoverished landless villagers in the repeatedly colonized Northern Poltava region, and the organization of the gang inspired by the haidamaky units.

The authorities of that time employed significant resources to hunt down the criminals. But they could have escaped into the territory beyond their control – to the right-bank Ukraine as haidamakyrebels, for instance. Meanwhile, the regime of Russian Empress Anna Ivanovna and Ernst von Biron was more concerned with persecuting old believers around Starodub, a city that had been part of the Cossack Hetmanate in Nortern Ukraine but is in Russia today, or casting the participants of the Ice House Clown Wedding entertainment show Anna initiated. Eventually, as a result of the war with the Ottomans de facto occupying forces of 75 Russian units in 1737 and 50 in 1738, all maintained at the expense of the local population, intervened into the left-bank Ukraine.

The case of the most notorious Ukrainian cannibal does not fit into the romanticized image of the late Cossack Hetmanate period. In the spring of 1740, Matsapura’s gang terrorized remote villages and hamlets in Pryluky, Lubny and Pereyaslav garrisons. The sadists killed 27 people and committed hideous crimes of cannibalism. The latter were always accompanied by ugly rituals initiated by the self-proclaimed magician, haidamakaIvan Taran. The horrors stopped when the backbone of the gang, four out of its 16 members, were arrested. The demonstrative execution of these violent criminals brought a fair end to this terrible story.

[1] James (Jacob) Keith fought for the independence of Scotland. He was colonel in the Spanish army and general-in-chief of the Russian Military, one of the first Masons in Ukraine and Russia. Keith headed the Hetman Government from July 6, 1740 through 1741, de facto acting as the Hetman of the left-bank Ukraine appointed by the Russian tsar. In 1747, he switched to the Prussian army and became field marshal there. From 1749 to 1785 he was Governor of Berlin. Keith died in the Seven Years’ War.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook