Last year, Ukrainian banks found themselves caught up in a liquidity crunch, provoked by the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU). Interbank overnight rates exceeded 50% while the average interest rate on hryvnia-denominated deposits was 25%. Interest rates are now lower. However, the underlying problems remain unresolved, going from serious to chronic.

EUROPEAN BANKS FLEE

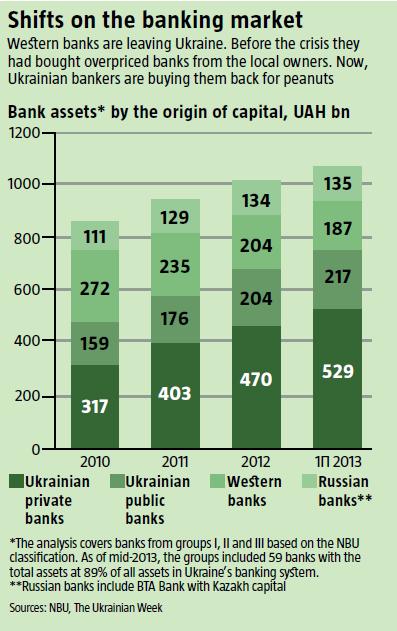

Despite the overall illusion of stability, the situation with individual banks and their groups seems much more worrisome. The banking market is undergoing redistribution: while some banks struggle to make ends meet, others are put up for sale, and some buy up their competitors on a massive scale (see Shifts on the banking market).

Over the past three to four years, around ten European banks have left Ukraine. The process continues. Bankers claim that a few more Western parent banks are looking for buyers for their Ukrainian subsidiaries. Recent examples include UniCredit’s UkrSotsBank and Raiffeisen Bank’s Aval.

According to one banker, when Europeans entered the Ukrainian market before the 2008-2009 crisis, they had no clear strategy for the local market. Their goal was the fat profit they could earn on the margin between cheap money borrowed in Europe and expensive loans issued in Ukraine. In the process, Western bank executives did not think about what they would do with their Ukrainian subsidiaries in the post-crisis recovery – at this point, they are not making the expected profit. It dropped from 13% in 2007 to 1.3% in the first nine months of 2013. Now, they are waiting in line to leave the market. The European debt crisis, coupled with the specifics of the Ukrainian business environment, seems to further encourage them to do just that.

READ ALSO: Foreign Banks Flee Ukraine

As a result, the assets of banks with Western capital (I-III groups based on the NBU classification) in Ukraine have shrunk by a third over the past two and a half years, dropping from UAH 272bn to UAH 187bn. European banks have taken technological innovativeness, the quality of services, liquidity, fairness and transparency with them.

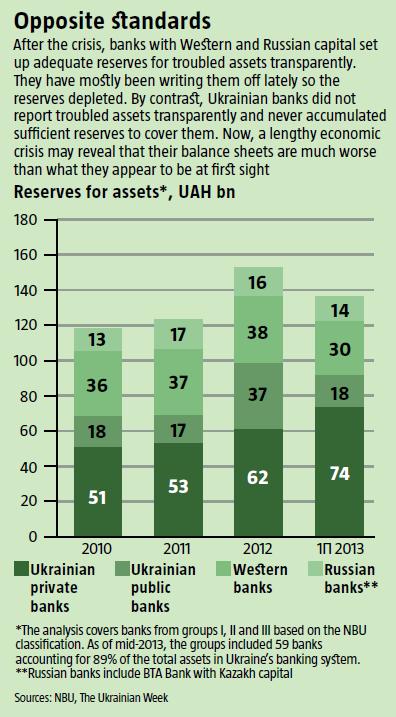

The dynamics in accumulating provisions for bad assets (see Opposite standards) is a perfect illustration of the loss of transparency. Right after the 2008-2009 crisis, most subsidiaries of European banks accumulated transparent provisions for bad debts and other toxic assets. By the end of 2010, they had almost UAH 55bn or 20% of total banking assets. They declared the provisions – and suffered relevant losses.

The loss was triggered by the local business practice. The oligarchs who owned the banks before selling them to Europeans used them to lend to their other businesses. These loans remained on the banks’ balance sheets as they were sold to Europeans before the crisis, which gave oligarchs an excuse to not repay the loans.

As a result, European owners wrote off half of their provisions over a period of two and a half years, since they could do nothing to collect the bad loans. This encouraged them to sell their loan portfolios to Ukrainian banks at knockdown prices. These turned into profitable assets in the hands of Ukrainian bankers and collection agencies who still remembered their loan collection practices from the 1990s. When, after the government changed in 2010, a campaign to oust Western subsidiaries from the Ukrainian market began, with the occasional use of administrative leverage, the exodus of Europeans became just a matter of time and price.

UKRAINIAN WILDLIFE

Now, Ukrainians are buying back Western subsidiaries with clean balance sheets, optimized cost efficiency and high liquidity buffers of an average of 0.2-0.6 of the bank’s capital. Such acquisitions ,coupled with NBU assistance to bankers it is close to, have boosted the share of Ukrainian banks on the market, their assets growing by 2/3 from the end of 2010 through mid-2013, and 36% for state-owned banks (see Shifts on the banking market).

READ ALSO: Capital Outflow

However, banks still have extremely low provisions for bad assets. A lengthy recession will only aggravate their troubles. Their liquid assets are also very low, with the ratio of cash and cash equivalent to total assets at 11% in private banks and 8% in state-owned ones. The total liquidity of private banks is essentially ensured by two major banks – PrivatBank and Delta. The former has increased its liquid assets to UAH 32.2bn over the past 18 months, including UAH 7bn on correspondent accounts in the central banks of Latvia, Russia and Georgia where it is actively expanding its network and UAH 15bn in other non-resident banks. Delta Bank has increased its liquidity to UAH 10.3bn, half of which is placed abroad. It is using part of its liquidity to buy smaller banks and increase its presence on the Ukrainian market.

THE WHIFF OF A NEW CRISIS

With the ongoing recession and the depressed macroeconomic situation, the risks inherent to private Ukrainian banks are beginning to crystallize. If at least one of the following factors comes to pass, it could undermine the current misleading stability.

One is the critical mass of problem banks borrowing on the interbank market and failing to repay the loans. They thus infect other banks, causing a domino effect. Another is panic among depositors who will rush to withdraw their money as soon as they hear any alarm bells. Some are ringing already: some banks, albeit mostly small, are having a hard time returning deposits to their clients. The third factor is the downward spiral of the economy that will make some borrowers insolvent and turn their loans into bad debts.

READ ALSO: Questionable Improvement

The government is not responding adequately to these challenges. In the first case, it filters out problem banks from the market by helping to leak information about their problems to other bankers. As a result, sound banks cap credit limits for the troubled bank and the system retains liquidity. However, the toxic bank finds itself up in the air: it is bankrupt de facto but neither the regulator nor the Deposit Insurance Fund seems to notice that, and the bank continues to operate de jure, albeit incapable of returning deposits. Moreover, it continues to accept deposits from unaware clients at interest rates that are far above average.

In the second case, the central bank keeps a lid on the news to prevent panic. Instead, it unfolds propaganda about safe banks and encourages people to deposit their money while the banks offer good interest rates. If a panic does indeed start, the NBU can impose a ban on deposit withdrawal.

READ ALSO: Bank Reserves Diminishing

The third challenge is a time bomb, but the government continues to turn a blind eye to it. While economic recession is slow, it allows banks to hide bad assets and avoid accumulating provisions for them. Meanwhile, more and more junk accumulates on their balance sheets. This is not surprising as the crisis has pushed most enterprises into losses, making them incapable of repaying their loans. Plus, the government keeps milking them through ever-increasing tax pressure to patch holes in the budget, and squeezes hryvnias out of the real and financial sectors to keep the exchange rate unchanged. Banks roll over loans to some companies in the hope of at least get interest from them. What will happen when they can no longer afford to pay even that?

The longer the recession, fueled by an ineffective government policy continues, the fewer banks will remain afloat. The current troubles of some small banks may be red flags for deeper problems. A systemic bank crisis could just be a matter of time.