Four years have passed since the last crisis in Ukraine’s banking sector. Banks have been able to fix their balances with moderate success and began to show some profits only last year. There was hope that the condition of Ukrainian banks would continue to improve. However, a number of foreign-owned Ukrainian subsidiary banks have been sold, high interest rates have persisted, and some financial institutions are already having trouble returning deposited money to its clients. All this points to gloomier prospects and more problems for the banking industry.

BALANCING ON THE EDGE

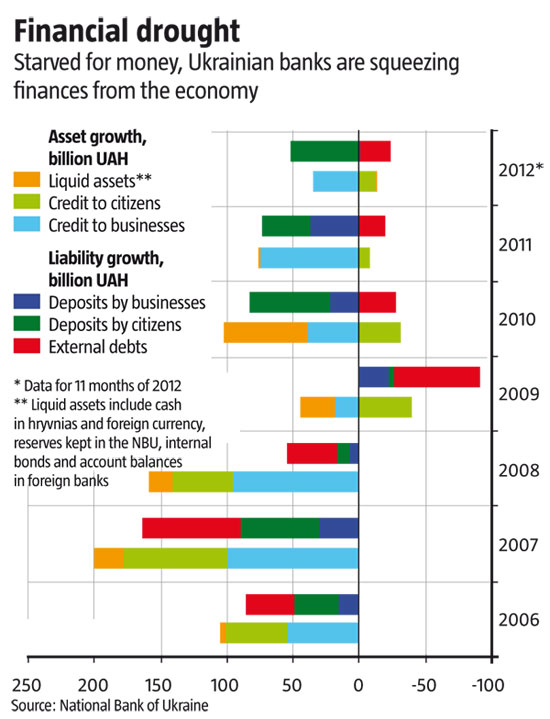

Ukrainian banks fundamentally suffer from a chronic deficit of financing. The key sources of financing are deposits made by individuals and businesses in addition to external loans. These account for 59% of all resources available to the banking industry, and any changes essentially redefine the terrain on the financial market (see the Financial Drought chart below). External loans were the main source of financing for the banking system prior to the crisis. It will take the banks a while to repay these – a mere 48% of December 2008 loans have been paid back as of the end of 2012. The situation is exacerbated by the disappointment of foreigners with Ukrainian banks and bankers. The latter may not see any large inflow of foreign capital for years to come, while old debts must be repaid in any case.

Not surprisingly, deposits took the lead as the main source of financing available to Ukrainian banks after the crisis. Lured by high deposit interest rates, Ukrainians deposited a lot of their money in bank accounts last year, but this may have simply revealed the maximum amount that they are willing to entrust to the banks. Moreover, people’s income will fall as the economy tumbles, which will force them to spend the money they now keep in financial institutions. Even a further increase in interest rates is unlikely to attract significant amounts of additional deposits.

Money deposited by businesses usually accounts for a large part of banking resources. Businesses make such deposits when they grow and need to have more circulating assets. However, there was no growth last year, so their accounts shrunk. Now there is every reason to expect economic decline or, at best, stagnation in 2013, so this source of financing will be unavailable.

Against this backdrop, it is interesting to see where banks channel the money they receive (see the Financial Drought chart). The short supply of money has essentially put an end to consumer lending. Banks are only getting their old loans paid back and issuing a tiny amount of new ones. All resources are being utilized to credit businesses. But this is not enough, and companies are choking with few circulating assets left after losses and taxes. Production volumes are falling, and factories have ceased to operate in many cases.

Not only businesses but also financial institutions themselves are lacking cash: they have not been able to increase their liquid assets (cash, foreign currency reserves, etc.) over the past two years. Thus, as the balance in the banking system improves, its liquidity and potential solvency is falling. Banks were able to maintain the status quo with liquid assets in 2011 but were forced to buy internal bonds in 2012, thus cutting into their hryvnia and foreign currency reserves. This exposes the system to additional risks, which may soon materialize.

NO RELIEF COMING

The National Bank would have to lend banks a helping hand in conditions of disrupted financing. In this situation, the central banks of most countries pour money into the system to boost economic growth. Developed countries have even gone a bit too far with this instrument in recent years. This does not apply to the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU), because its priority now is to ensure the stability of the hryvnia rather than economic growth. It would seem that the two macroeconomic objectives would have to complement each other, but the economic situation in Ukraine is such that they actually contradict each other. 2012 statistics confirm this and professional economists are aware of the issue, but the NBU’s management is turning a blind eye.

As a result, Ukraine’s banking sector has been operating in the following mode for more than a year now. Banks have been channelling all their financial resources into the anaemic business of their owners as a matter of first priority. The crumbs that remain have ended up on the interbank foreign currency market, which has expanded three to five times in the past two years. Realizing that any refinancing will be used to buy foreign currency, the NBU has issued credits only to loyal banks on specific conditions (such as purchase of internal bonds or crediting government projects) under which this money can never find its way to the currency market. The NBU knows exactly how much money (received interest rates, repaid loans, etc.) enters the banking system each month and has no problem calculating just the right volume of refinancing to avoid flooding the currency market with hryvnias and prevent uncontrolled hryvnia devaluation. Therefore, as long the hryvnia exchange rate is stable and devaluation expectations high, this scheme may work, even though it strips commercial banks of liquidity, as well as of a desire and capability to credit the economy.

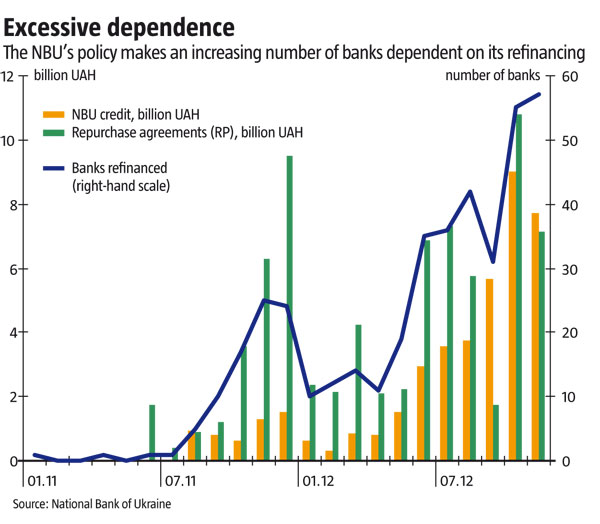

Of course, the National Bank issues many refinancing credits (see the Excessive Dependence chart), otherwise the banking system would have reached a critical point by now. But this money is not enough to secure even a short-term solution, to say nothing of economy-boosting credits. Refinancing volumes are rising, and as much as one-fourth of the banking system needed refinancing in late 2012. In these conditions, it is hard to predict which will happen sooner: a systemic crash of the banking system or NBU-orchestrated hryvnia devaluation.

SKYROCKETING INTEREST RATES

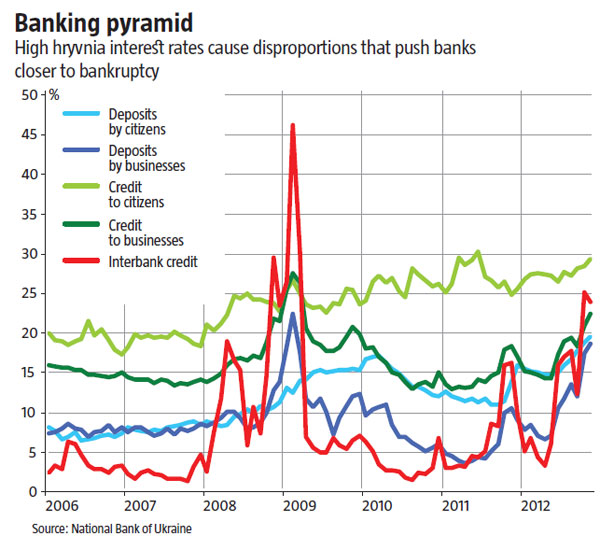

The condition of the banking sector is adequately reflected in interest rates. All key interest rates grew in 2011 and remained high in 2012, in some cases reaching historical highs (see the Banking Pyramid chart below). The interbank market is the first to react to a short or excessive supply of money in the system, and it posted the most significant increase in the cost of credit. The dynamics of interest rates in 2011-12 and 2008-2009 appear nearly the same: two shared waves and the same duration of the period leading up to a deep crisis. The only difference is the higher amplitude in 2008-2009 when the disproportions were bigger and the NBU had less time and knowledge to react properly. This comparison suggests that even if Ukrainian banks avoid massive problems in the near future, many of them will not survive until 2014, given the current trends.

Interest rates on hryvnia deposits are beating decade-old records. And this is the most massive resource available within the country. It looks as if banks are showing that they have only one option left as they seek sources of financing. And this single option is valued in hryvnias – interest rates on foreign currency deposits made by households are much lower than in 2008.

The high interest rates increasingly lose their effect with each passing quarter, while the rate of deposits received is falling. Interest rates on deposits made by businesses have been rapidly growing, but companies lack finances to serve their own needs, and so they watch skyrocketing deposit interest rates with an ironic smile. Interest rates on loans are, of course, also growing. Loans to physical persons became more expensive immediately after the crisis. For businesses, interest rates on loans are not growing as fast as on the deposits they make. All in all, despite a short supply of money and the need to survive, companies are not prepared to borrow money at the current rates and prefer to shut down and wait for better times. As a result, the economy and the standard of living in the country are falling. This hurt Ukrainians in the second half of 2012 and will continue to do damage in the future.

Interestingly, high interest rates have coexisted with a low inflation rate in Ukraine for quite some time. This is direct evidence that money is lacking both on the financial market, which defines interest rates, and on commodity markets, which define price levels. If money is lacking on both of these markets, neither the state nor citizens or businesses have it. This is a direct result of the NBU’s activity under Serhiy Arbuzov, who is an agent of the Yanukovyh regime’s “Family.” He has been moved to a government post and may eventually head the Cabinet of Ministers. In this case, it is frightening to imagine what the financial and political policy of the Family, which will likely maintain its control over the National Bank, may eventually lead to.

WHAT WILL BECOME OF THE BANKS?

Bankers will, no doubt, continue to scratch their heads over where and how to obtain financing. All current and potential creditors of Ukrainian financial institutions are gradually losing the motivation to trust them. Moreover, Ukrainian citizens and businesses as well as non-residents (largely European) are themselves experiencing problems, including loss of jobs, falling incomes, financial losses, etc. They will need money in order to overcome these hardships, so even this potential source is becoming depleted. The key rates will stay high as long as this fundamental trend persists. Therefore, the temporary drop in the interest rates the country saw in December 2012 raises more questions than it offers answers. If the increase in liquidity and the drop in rates were so insignificant and short-lived after the end of the election campaign and amid marked optimism on world capital markets, what will they look like when the situation is less favourable?

On the one hand, the NBU may continue its current policy of precisely measured refinancing. In this case, the high interest rates will continue to hurt bank balances. Some banks will go bankrupt, becoming completely dependent on the NBU and needing its refinancing for years to come. A worse outcome of this scenario would be a bank run and capital withdrawal abroad by bankers. Ukrainians know what this entails from the previous crisis.

On the other hand, the NBU could abandon the idea of maintaining the hryvnia’s exchange rate at any cost and instead carry out controlled devaluation which would reflect the macroeconomic situation. This move would have a double effect. First, resources would flow from the interbank currency market to credit, because there would be nothing to gain on that market if the hryvnia is adequately valued. Second, non-residents that have adopted a wait-and-see approach would start investing more actively in Ukraine’s economy. This would bring more money to the banking system. Moreover, the population would realize that an influx of money reduces the risk of bankruptcy and would be more willing to deposit money that it now keeps at home in cash. Furthermore, the NBU’s refinancing would reach its goal of lending credit to the economy, because bankers would no longer have reasons to channel the money they will be receiving elsewhere. An additional benefit is that refinancing may actually turn out to be unnecessary – as is known from the past, interest rates drop and banks’ liquidity rises almost overnight in this case.

Is there a possible third scenario? Theoretically, it does exist. But it would require the world economy to enter a phrase of rapid growth, Ukraine to greatly improve its investment climate, Ukrainians to begin trusting their government and Ukrainian businesses to come out of the shadows en masse. All of these circumstances are unlikely.