Since 2009, more and more European banks have left Ukraine, including ING Bank, Home Credit Group, Сredit Europe Bank, Societe Generale, and Volksbank International. Swedbank sold SEB Bank assets to a Ukrainian businessman, and other banks simply left the retail market. The outflow of foreign capital is having a heavy impact on Ukraine’s banking system. The 2006-2008 credit boom and the surge of loans issued in foreign currencies were fuelled by cheap European money. However, the 2008-2009 crisis showed that the presence of private Western banks in Ukraine was a vacation from bigger troubles rather than a burden for the Ukrainian market. Capital inflow from Europe changed the face of the Ukrainian banking system for the better by improving bank service culture and giving Ukrainians broader access to loans than they had ever had. The tables turned when foreign banks began to lose ground to captive banks owned by oligarchs that mostly lend money to their own companies. This is a sign of the growing strain on business in Ukraine.

A WINDOW TO EUROPE

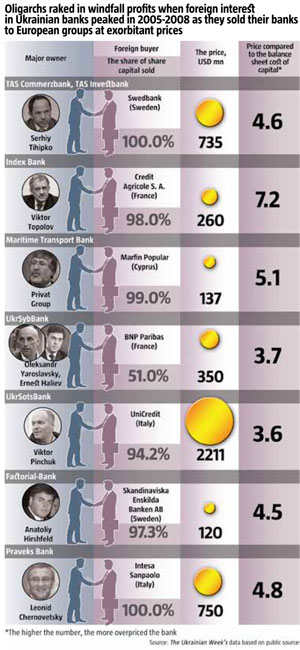

The financial sector is typically a barometer for changes in long-term investment expectations for Ukraine. Even though foreign capital had been present in Ukraine’s banking sector before the 1998 crisis, 2005 proved to be the real breakthrough year. Driven by post-Orange Revolution exuberance, European banks began to buy Ukrainian banks one after another, often paying sums that were several times higher than what the actual assets of the banks were worth at the time. In 2007, at least 10 Ukrainian banks found themselves in the hands of foreign owners. Good deals turned Ukrainian oligarchs into dollar billionaires overnight – mostly because of the overheated banking sector. The prices paid for banks ranged from 2.6 to almost 5 times their equity value – the latter was paid for Praveks Bank. To justify the gargantuan prices, the purchased bank was expected to provide sustainable rapid growth in assets at over 12% annually, a 20% annual ROE increase and a 15% equity value growth. The 2008-2009 crisis proved that these had been unrealistic expectations.

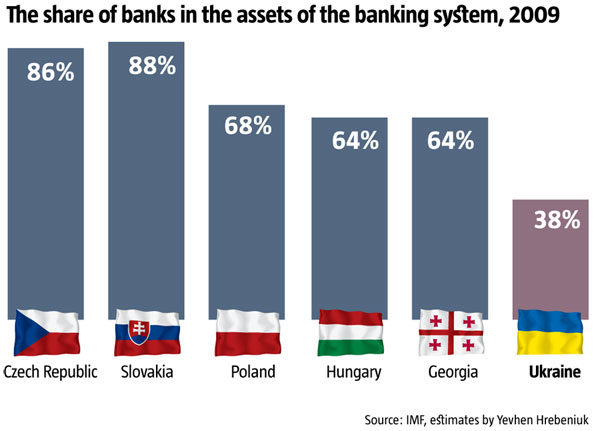

Eastern European countries quickly grasped the idea that opening their financial sector to foreign banking groups granted them the easiest access to Western investment into their economy. According to Raiffeisen Bank, the share of foreign capital is 73% in Central Europe and 83% in South-Eastern Europe. The Czech Republic and Slovakia have come the closest to foreign banks in terms of transparency. The share of foreign – mostly European – banks is close to 90% there and neither the government nor clients view this as a threat or a source of damage.

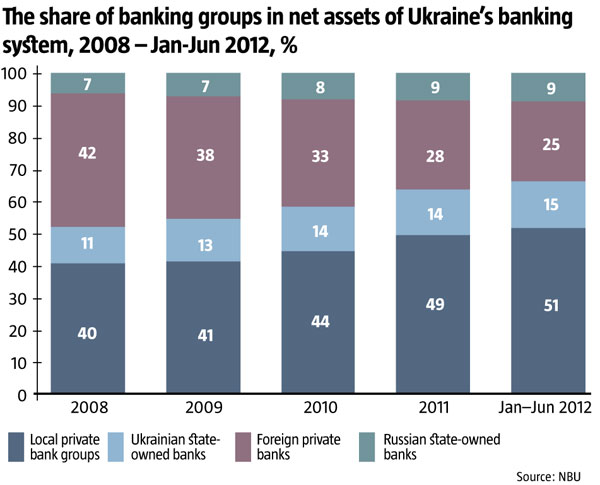

The massive inflow of European banking groups to Ukraine had a largely favourable impact on the economy. Unlike the mining industry, where most FDI comes from the oligarchs’ repatriated profits, European newcomers in the banking sector brought along new foreign direct investment. According to the National Bank of Ukraine, only 7.7% of the cumulative FDI into the share capital of Ukrainian companies went to the financial sector in 2004. In 2008, the figure was almost 30%. Over 2006-2008, nearly 42% of the $26 billion foreign direct investment in Ukraine went to the financial sector as foreign interest in Ukrainian banks peaked. European groups did not abandon their subsidiaries during the crisis. In 2009-2010, they invested over UAH 17bn of new share capital in the Ukrainian banking sector, which was 67% more than what the owners of local banks invested. Moreover, foreigners used subordinated debt much more intensely than the local bankers did. As a result, almost half of the UAH 34bn subordinated debt is that of foreign private banks.

Another obvious effect was the unprecedentedly broad access to retail lending available to average Ukrainians from 2005-2008. The mortgage loan portfolio alone swelled sevenfold over 2007-2008, even though foreign banks preferred to place foreign exchange risks on the borrowers. They issued the greater share of mortgage loans in dollars. As a result, the amount of bad loans soared in 2009-2010.

The inflow of European banks had a great indirect positive impact on the banking sector and Ukrainian economy overall. First, they brought in new standards of corporate governance and customer service. European banks in Ukraine have clear rules for risk management which, if violated, may result in the firing of the local executives. Thus, a foreign bank will never pick up deposits from the retail market to further issue them as loans to linked companies. By contrast, quite a few of their Ukrainian peers eagerly do this, revealing their likely status as captive banks of big business groups. Most European banking groups are public companies, their operations closely watched by shareholders. The statements of their Ukrainian subsidiaries are prepared and audited under international accounting rules identical to those used by their parent banks. Shareholders hold them accountable for the failures of Ukrainian executives, and their punishment may be falling stock prices.

The owners of European banks are groups that have no companies in other industries. Their interests lie in the orbit of the banking business. It is hard to imagine a situation where a parent bank based in Europe instructs its Ukrainian subsidiary to issue a loan to a specific company or to overlook the rules for issuing loans to one borrower or associated entities. Unlike them, most bank owners in Ukraine have other primary businesses and use their banks as donors more than anything else in times of crisis. Officially, they comply with the NBU’s restriction on lending more than 25% of the regulatory capital to one borrower. Yet, some sources suggest that the real level of insider lending in some captive banks may exceed 50% of the total loan portfolio. The regulatory authority does not monitor the entities of big business group owners deeply enough to determine this.

Subsidiaries of traded Western banks operate in compliance with high standards of corporate governance and treatment of minority stakeholders. UkrSotsBank which is part of the UniCredit group recently made an unprecedented redemption of shares from minority shareholders at their market price in accordance with the law.

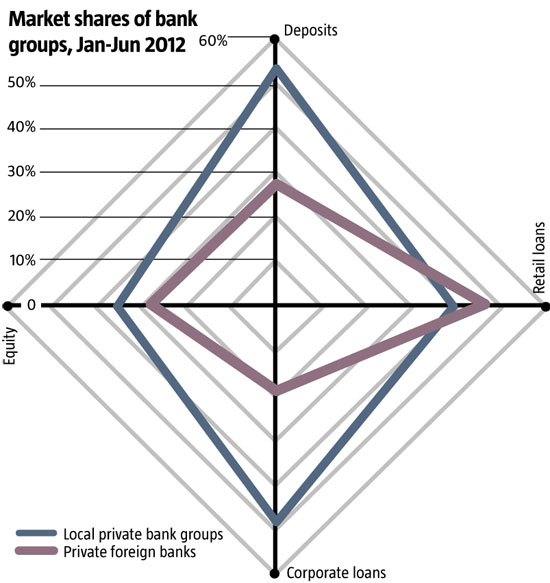

Unlike most private foreign banks that use their parents’ equity for retail loans, Ukrainian banks use deposits from individuals for that purpose. Hence the answer to whether the broad public is interested in the presence of private Western banks. The intense increase of the European share in the Ukrainian banking system over 2005-2008 has essentially squeezed captive banks to the sidelines. Some oligarchs even gradually switched to using universal European banks with high standards to service their companies. It was definitely cheaper for them compared to maintaining and developing a bank of their own.

OLIGARCHS OUST EUROPEANS

Since 2010, Ukraine has seen a reversal of the European banking trend. The growing pressure on businesses and resurgent fear of property loss have once again fuelled the demand for captive banks, just as they did in the 1990s and early 2000s. In a prime example, a German group recently sold its Ukrainian bank to a local oligarch. On the whole, the share of private Western banks save for state-owned Russian banks shrank from almost 42% in early 2009 to 25% in the first half of 2012, mostly in favour of local Ukrainian banks. A few more banks with European capital may end up in the hands of Ukrainian owners by the end of 2012.

The expansion of Russian state-owned banks including VneshEconomBank (VEB), VTB and others, has been a separate trend. State-owned banks operate in many countries and help the government to perform some social functions. Obviously, Russian state-owned banks have provided much broader access to loans for mostly big Ukrainian companies. This was a positive contribution to Ukraine’s economy. One of Russia’s most proactive banks is VEB which is, in fact, a quasi-bank regulated by a special federal act. Whenever a European government becomes a shareholder of a bank, it sets some restrictions on the growth of its assets, sometimes pressuring the bank to quit risky foreign markets. Quite the opposite for Russian state-owned banks: they are actively expanding abroad thanks to financial resources granted by the government at prices below market value. Essentially, this means that they are building networks in other countries at the expense of Russian taxpayers. Hence the question: what purposes does a foreign government serve by approving the expansion of its state-owned banks abroad? Russia’s first priority is to invest the huge amounts of cash it is earning on fuels (Russia’s current account surplus over the first six months of 2012 was $58 billion). However, the Kremlin is actually an insider to Russian state-owned banks, thus their unprecedented international expansion cannot be without political motivation.