Capital travels across the globe in the blink of an eye in pursuit of profit. A country that offers plenty of options for more efficient business or the production of new goods or services is the perfect destination. As soon as new ideas run out and managers relax – which is inevitable sooner or later – capital disappears. Emerging markets are going through this right now. Their economies are slowing down and there is no motive for capital to remain there.

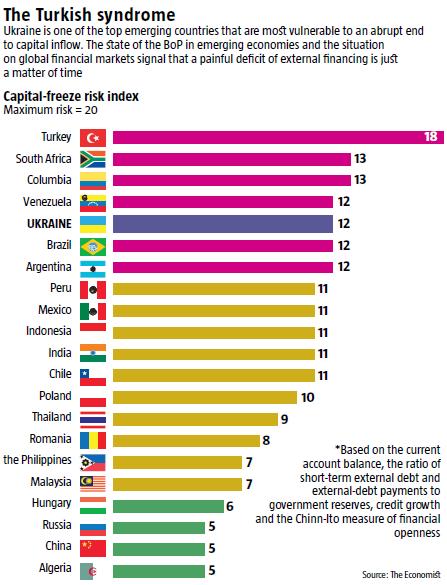

Earlier this month, the business magazine, The Economist, published the Capital-Freeze Index (see The Turkish syndrome). Its 20-point scale assesses the vulnerability of emerging economies to an abrupt halt of capital inflow based on four variables. These including the current account balance, the ratio of short-term external debt and external-debt payments to government reserves, credit growth and the Chinn-Ito measure of financial openness. Ukraine scored 12 points and landed fourth to seventh of 26, together with Brazil, Argentina and Venezuela. Its risk for a sudden stop of external financing is among the highest.

MISLEADING IMPROVEMENTS

Most experts note two negative aspects in Ukraine’s balance of payments. The first is the huge current account deficit. It seemed to decline slightly in the first half of 2013, but this improvement was orchestrated and temporary. The latest trade conflicts with Russia will already have a palpable negative impact on Ukraine’s trade balance by the end of 2013.

However, a bad deficit can always be covered with borrowings and the inflow of foreign investment. It does not necessarily signal that there are real problems. Countries can live with current account deficits for years, and many do.

The other negative factor is the outflow of foreign currency in cash from the banking sector, as Ukrainians buy it up. However, this, too, does not look all that critical: the leak of foreign currencies from banks in the first seven months of 2013 fell by 36% compared to the same period in 2012.

READ ALSO: Unnerving Business

With the abovementioned positive trends, many could have the impression (quite a few analysts actually do) that Ukraine’s balance of payments is in good shape. They ignore the fact that the government stopped borrowing from abroad five months ago or that Ukraine’s international reserves have dropped 12% since the beginning of the year to USD 21.7bn as red flags. Many expect the window of liquidity to open later and boost both borrowings and reserves. This is a misleading illusion. They fail to take into foreign borrowings of the private sector into account, which make the illusion of stability widely promoted by those in power null and void.

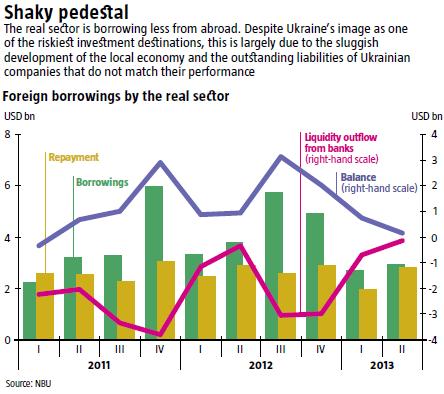

The taken loans and issued bonds by the real sector are a key element of Ukraine’s balance of payments (see Shaky pedestal). In 2011, net inflow of foreign currencies in the form of loans and bonds for the real sector covered 41% of the current account deficit. In 2012, it covered 47%. Ukraine was living in debt, but this was largely incurred by businesses.

But this year, things have changed. The non-financial sector has been borrowing less from abroad. Yet the volume of its repayment is not falling, as loans taken earlier are due. As a result, the net inflow of foreign currencies from corporate non-bank borrowings was negative in three of seven months in 2013. It covered only 11% of the current account deficit over January-July. The situation would be even worse if, on the orders of the government, state-owned companies and banks, including UkrZaliznytsia (the Ukrainian Railway), UkrAvtoDor (Ukrainian Roads), OshchadBank (Savings Bank) and UkrEximBank, had not gone to global markets as intermediaries seeking borrowings to support the budget. Some of them do not need funds for development. They mostly had UAH 8-10bn in cash on their bank accounts during the past three years. In December 2012, their balances grew to UAH 20bn but dropped to UAH 18bn by early August 2013. This signals that state-owned companies borrow abroad, then deposit the money in banks chosen by the government. These banks then buy government bonds. So far, statistics for borrowings abroad have looked good, but this will not last.

GLOOMY PROSPECTS

Manufacturing companies will have to repay more and more principal of the debt accumulated in previous years, but will be unable to continue to borrow in the amounts to which they have become accustomed. The first reason for this is the situation on the global financial market. While trillions of dollars still circulate there, searching for profitable businesses, the investment trend has been sustainably negative since the beginning of 2013. Capital is flowing out of developing countries on a massive scale, including from a number of Asian economies that had enjoyed rapid sustainable development and provided a lucrative return on investment in recent years. As a result, their currencies become devalued to adjust their financial systems to the new reality. The hryvnia is not following suit, so the expectation of devaluation may speed up capital outflow from the real sector. Economic decline, the sluggish development of the financial system, the huge current account deficit and openness to capital outflow will not make things better.

READ ALSO: After Them the Deluge

Ukraine could avoid this global outflow trend, since its appetite for foreign capital is meager on the global scale. But domestic business would need good fundamentals to stop it, which sadly, it doesn’t have. On the one hand, Ukrainian non-financial business had an adequate leverage ratio, i.e. the level of internal and external borrowings from banks with interest to equity, at the beginning of 2013. It was nearly 60% a normal standard of less than 100% and over 200% being critical. The interest-bearing external debt of the real sector that does not include trade loans and intercompany debt was USD 43.9bn at the end of 2012.

On the other hand, the ratio of internal and external debt to the operating results of Ukrainian enterprises looks much more depressing. In 2012, the debt to EBIDTA ratio was 3.1 for all non-financial companies with up to 3 being normal and over 4-5 being critical. Their interest coverage ratio (EBIT to interest payments), which shows how easily a company can pay interest on the outstanding debt, was 1.9 with over 1.5 being normal and less than 1 – critical.

READ ALSO: Mothballed Banks

Since Ukrainian enterprises reported 74% less gross earnings in H1 2013 compared to the same period in 2012 (down from UAH 29.2 to UAH 7.6bn), the abovementioned ratios may already sink to the critical point this year. As a result, Ukrainian banks and non-resident financiers will stop lending to local business. So, a halt in capital inflow to the real sector may be accompanied by a surge of bankruptcies in private business. Some red flags already signal this. This is hardly surprising: if it could develop, business would earn the income to repay its mounting loans. This would encourage financiers, including international ones, to lend money to business. Capital inflow would boost economic development. However, the government is hampering the development of entrepreneurship, so the impact of its policy is yet to be seen, particularly for the balance of payments.

It appears that the net borrowings of the non-financial sector that compensated the outflow of foreign currency in cash from banks in recent years (see Shaky pedestal) will inevitably plummet. Coupled with the current account deficit that will grow again after a temporary improvement and the massive buyout of foreign currencies by Ukrainians (in August, for the first time in the past five months, Ukrainians bought more foreign currency from banks than they sold), this could tip the hryvnia exchange rate. Manual methods will not work here. The only option for the government is to develop business. But to do so, it should admit its mistakes, reverse its budget and fiscal policy, and learn patience.