Most of the people I spoke with in Luhansk and Donetsk take no offence at the seemingly caustic catchphrase, “Thank you, people of Donbas, for the president…[the rhyme of the day which ends labelling the president with a vulgar term of no-endearment — transl.]” In the two years it has been in power, the government has managed to hurt its core electorate which is now beginning to understand that there is someone to be held responsible for their lost illusions. The impression is that Viktor Yanukovych & Co. will find no forgiveness here for their failed promise to deliver “a better life even today” simply because they are natives of the region. The level of discontent in Donetsk Oblast has yet to reach the critical point of open rebellion, but things are steadily moving in that direction.

THE ENEMIES WITHIN

“I always voted for Yanukovych, but he turned out to be (expletive),” Andriy Aloshknin, ex-coalminer from Antratsyt and now a general labourer in Luhansk, says emotionally in response to the question about what ordinary people in the Donbas think about the government they elected.

In the past year and a half, the sociopolitical attitudes have reversed here. In 2010, there was certain revanchist optimism – “our guys finally won.” In the first half of 2011, people grew indifferent to politics as such, and now the level of discontent with what would seem to be “their” government is beginning to reach critical heights. The current president and his fellow party members risk antagonising their core constituents. Speaking off the record, some regional leaders admit that the government is greatly concerned about Eastern Ukraine now – the Party of Regions is afraid of losing it in the next election.

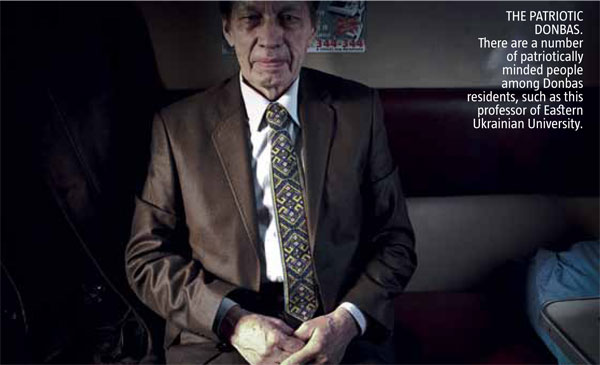

“I asked a fifth-year student who she will you vote for?” Serhiy N., professor at Vladimir Dal Eastern Ukrainian University says. (Most people in the Donbas are still traditionally afraid of openly calling a spade a spade. – Author). She replies: For the Communists. I ask: Why? She replies: Well, my grandfather said that's the right thing to do. This is unfortunately a very common situation here. The old vote following their habits, while the young either do not show up at polling stations or are totally indifferent. But not everyone is like that. More and more citizens are beginning to think with their heads. For example, I will support democrats no matter how bad they may be – they are still better than the so-called ‘our guys’. The key problem for many people is the lack of an alternative. Of course, some will rush to cast a ballot for the Communists, but people that know better are at a loss.

However, the idea “He is a son-of-a-bitch, but he is our son-of-a-bitch” which seems to have been fixed forever in their minds seems to be giving way, despite the fact that “Donbas does not change its mind.” In the past two years, the standard of living of the average citizen in the region plummeted. The gap between expectations and realities is too wide, especially against the backdrop of some people’s estates growing by leaps and bounds. “I hate this man Yanukovych,” an old Georgian taxi driver says almost spitting, “In 2010, I told all my passengers to vote for him. Now I am ashamed to look them in the eye. How can prices here be higher than in Kyiv? It feels like everything is being done at our expense. Do they think we are idiots or what?”

Paradoxically, two absolutely different perceptions of the current government and government as such coexist in the minds of Donbas residents. On the one hand, these people are utterly hostile to anyone or anything that symbolizes the government. “Vampires” is a description that can often be heard from the locals. On the other hand, next to this inborn anarchy characteristic of inhabitants of the steppe is absolute conformism that sometimes takes the shape of indifference. Most are now somewhere between indifference (people simply do not care who is in the government, because they reject it altogether) and naked hatred.

“WHAT WILL COME, WILL COME”

Even though many Ukrainians still vividly remember coalminers banging their helmets against the pavement in Kyiv in the early 1990s, it turns out that the real number of passionate citizens in the Donbas – and those who are aware of their interests and are willing to defend them – is minuscule. Most locals believe that fighting for their rights, especially in coal mines or plants, will destroy their income. Moreover, they simply do not stop to ponder the issue as they are too busy trying to survive in the current conditions which they view as a given. “When you work and keep silent, they put you in a good sector in the mine,” Oleksandr Syhyda, poet and former coalminer from the village of Atamanivka near Luhansk, explained. “You can even make a thousand dollars. And if you start saying too much, they won't fire you. Why should they? They'll simply assign you to a bad sector, and your salary, which depends on your output, will take a nosedive right away. So you can risk your life every day for UAH 1,500 a month and be freedom-loving or keep things to yourself and earn good money. Everyone makes the decision himself. But people have somehow got used to risking their lives – it comes with the territory.” Indeed, Donbas residents are surprisingly fatalistic. “What will come, will come” is a slogan that best reflects their thinking.

The surprising thing is that coalminers tolerate such inhuman working conditions, a large number of deaths and great risks. (Not all of them earn $1,000 a month.) However, the people with whom the author spoke are unanimous in admitting that mine directors are not alone to blame for accidents. “Trust me, in soviet times we had a great number of accidents like the one in the Sukhodolska mine (where 28 died in 2011. – Author),” Syhyda says. “There are even fewer now. The thing is that accidents were hushed up back then, even though they were just as bad. Note that they most often occur in August. Why? Because like in soviet times, miners have to have record amounts of coal mined ahead of Miner's Day. And it was back then that they learned to stuff rags into methane sensors so they wouldn't interfere with their work. You see, the alarm system goes off as soon as the concentration of gas in the air even slightly exceeds the norm. Accidents are caused most of the time by miners and their neglect for their own safety.”

“As harsh as it may sound, 90 per cent of coal miners are silent slaves,” says Kostiantyn Ilchenko, leader of the Solidarity Labour Movement from Sverdlovsk, Luhansk Oblast. “For example, Hennadiy Zimin, my colleague in the trade movement, fought the local coal and drug mafia and, as a result, became disabled and lost all his property. But he is probably the only one like that in the entire city. This crowd will never grasp anything. You talk to them and explain that they need to defend their rights because it's their money, and they are silent. As soon as their foreman has passed by, they pat you on your shoulder and say: “Good! You're doing everything right. You're defending us.” But when he comes back, they act as if they don't even know you. So what can activists change if, for example, our Joint Action trade union has 10-15 people in one enterprise – and not in every mine – while there are at least 200-300 working in one mine? But when they wake up, it will be quite something. And this will happen soon, because it is becoming increasingly difficult to survive.”

Donbas settlements are being swept by a wave of pent-up hatred which so far is vented only at kitchen tables after a few shots of vodka or during traditional chats over a meal before going down into the mine. It is also revealed in an increasing number of assaults and robberies committed against wealthy Donbas residents – council members, businessman and government employees. “The police now simply do not show the real crime statistics,” Ilchenko says. “And this is a very bad tactic, because most of the local residents are still an inert herd. But as soon as they grasp that it is possible, almost like back in the 1990s, to go to your neighbour who has meat in his fridge, poke a fork in his eyes and take his cutlets, things will turn atrocious. The Party of Regions itself does not understand what it is doing and what demons it is releasing. In the 1990s, people still had some illusions, so they somehow survived the hardships and six-month delays in salary payments. Now they have neither fear nor conscience – just a desire to somehow earn money in conditions when enterprises stand completely looted. As soon as someone does something openly, all of it will explode, and this criminal fire will be unquenchable.”

Crime is in general very characteristic of Donetsk Oblast. The reason is not even that it has Ukraine’s highest concentration of prisons. The underworld has permeated everything and has become synonymous with “manhood”. Criminals have mostly been sent to local prisons since soviet times. The official reasoning is that it is economical – relatives are nearby, so less is spent on food. Incidentally, the road to the local prison in the now infamous town of Sukhodolsk looks much better than its main street.

MONEY DONBAS-STYLE

In Luhansk, passengers pay the fare when they get off fixed-route buses, not when they board like in most Ukrainian cities. There seems to be a vestige of the Soviet Union in this. Can it be that these rules have something to do with the local mentality – that people perhaps perceive these vehicles as a kind of taxi? When you read the names of a bunch of streets, which probably have not changed since soviet times, this daring theory stops feeling like a mere intellectual pastime. The central street – Sovetska (Soviet) – sets the tone for world perception.

According to official statistics, a person in Donbas earns more than the average person in any other region besides Kyiv. The salaries of many people employed by metallurgic works or mines are indeed relatively high – UAH 7,000-8,000 in state-owned enterprises. Jobs in illicit mines are also valued: a coalminer can earn UAH 300-500 and a winchman UAH 150-200 a day. The private sector in Donetsk offers monthly salaries (paid unofficially) that are close to the rates in Kyiv – $500-1,000. But small towns are in a fix.

“It has been so since soviet times,” Syhyda says. “Coalminers spend their earnings on alcohol and their houses have fallen apart. Our people are changeable.” A typical sight in the Donbas is entire blocks of semi-abandoned houses, as well as ghost towns and settlements formerly inhabited by the employees of now closed or bankrupt mines and plants. The picture is apocalyptic.

Many people here hoped that when “their” government rose to power, they would be able to earn some money. Instead, the business climate in the region has greatly deteriorated in the past two years. The locals are unanimous: the people they elected are solving personal problems at voters' expense by channeling finances to any other pockets or regions besides theirs. “An acquaintance of mine saved some money and decided to open a private mine,” builder Sashko from Luhansk says. “To start with, he wanted to do everything honestly — and he did. But when he came to the tax administration to pay taxes for the first time, he immediately realized he had made a mistake. He calculated the sum and entered it in the declaration, but his tax inspector said ‘No, that won’t do’ and tripled the original amount. The message was: Either grease my palm or pay the triple amount honestly, as I said. Of course, he paid a bribe and shut down the mine the next day. And of course that was a formality – the enterprise turned into an illegal mine and has been operating ever since. He pays the right people in the tax police and the district administration when he needs to. Everything seems to be all right. No-one has bothered him yet, but they demand more with each passing month. He is thinking about shutting down his business.”

You can take either a tram or a fixed-route bus from Donetsk Train Station to the city centre. If you take the bus, you soon arrive at a shiny, contemporary business centre – Akhmetov City, as the locals call it. If you take the tram, in just 20 minutes you will find yourself in slums that can only compare to Brazilian favelas. This is a miniature image of the entire Donbas. The locals used to tolerate these contrasts but now they are outraged by them.