A swimmer’s performance depends on the water in which he swims, its temperature, chemical composition and waves. Banks similarly depend on the economic environment in which they operate.

Ukraine’s GDP remained over 5% short of the pre-crisis level in 2010-2012. The economy has been in downfall and recession the past three quarters, and experts, international financial organizations and rating agencies are not optimistic about 2013. The industries facing negative trends include processing, construction, transportation, steel production and chemistry, to name a few. These economic conditions are hitting the state budget hard. The budget deficit for 2012, less the deficit of NaftoGaz Ukrayiny, was twice that of 2011, reaching UAH 53.5bn. Four months into 2013, the budget deficit was UAH 16.2bn compared to only UAH 4.5bn over the same period in 2012. Meanwhile, budget revenues were lower in April this year compared to April 2012.

READ ALSO: The National Budget and Bureaucratic Brazenness

The fundamental problems of Ukraine’s economy show in the balance of payments. The current account deficit grew from USD $3bn to USD $14.8bn in 2010-2012, compared to USD $12.8bn in the crisis year of 2008. This is close to the balance of trade worth USD $14.8bn. In this case, where did the money come from to buy the imported goods and services? The government took funds from foreign-exchange reserves and borrowed money thus boosting government debt. In 2011-2012, the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) sold a net of USD $11.2bn from foreign exchange reserves, compared to USD $10.4bn in the crisis year of 2009. How did the crisis differ from the “recovery”? Moreover, foreign exchange reserves were higher back then. Another source of foreign currency is the growing government debt. It grew by almost USD $25bn from 2010 to 2012, adding another USD $4.7bn over the first four months of 2013. In 2009, government debt per capita was around UAH 7,000 or USD $864. Now, it exceeds UAH 12,000 or USD $1,480. Sooner or later, Ukrainians will pay this through inflation and devaluation.

Keeping the hryvnia exchange rate stable and inflation low has been the government’s strategic goal for the past three years—one that damaged both the economy and the banks. The government accomplished these political goals through a liquidity crunch in 2011 and 2012. The deficit of hryvnia that was manually kept out of the economy and artificial rise of the hryvnia exchange rate froze production, knocked GDP down and increased the debt burden on banks. The stable hryvnia cost Ukraine the stifled economy, a government debt 1.75-times larger than that of 2010, and the sale of foreign exchange reserves worth USD $11.2bn over the past two years. All these negative economic trends are damaging the banking sector. The artificial liquidity crunch in 2011-2012 boosted the cost of bank liabilities. From January-April 2013, banks earned 8.3% on interest rates, while spending 21.9% to cover interest on their own liabilities. Over 2012, interest income grew 3.7% while spending to cover interest charged on banks went up by 14.6%. This trend began in the last quarter of 2011.

READ ALSO: Only For the Chosen

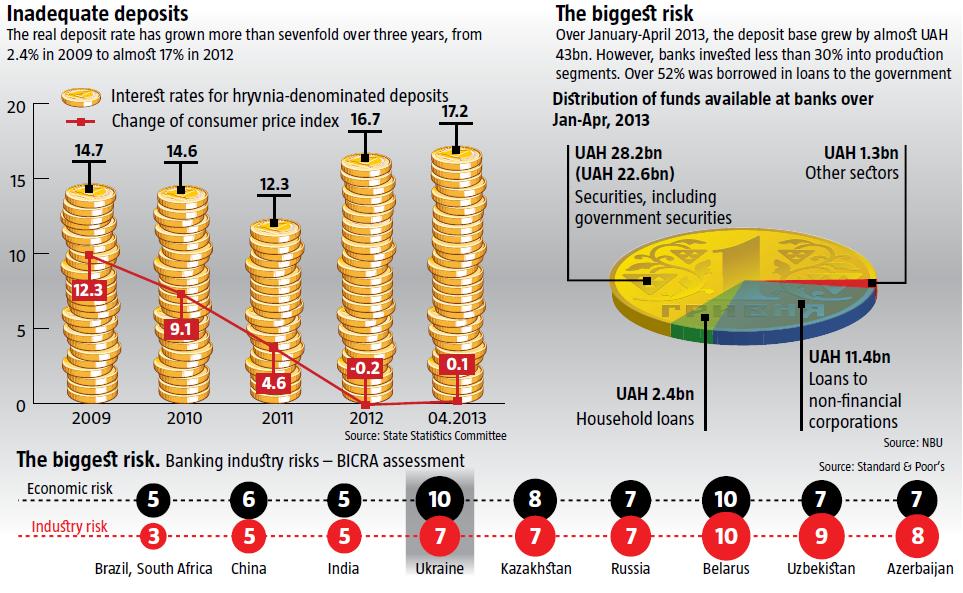

The deposit rate as a difference between the interest rate and inflation has grown seven times over the past three years, from the normal 2.4% in 2009 to almost 17% in 2012. This signals the extent of the manually created hryvnia deficit, deposit risk growth and lending to the production sector hampered by high credit interest rates. Over four months of 2013, the deposit base grew almost UAH 43bn. Household deposits increased 8% over this period. Less than 30% of this newly-drawn funding went to the production sector that creates the added value. Instead, over 52% was used as credit to help the government deal with its budget problems. The government spends this on social benefits rather than production. Where will it get the money to return it to banks under the current state of the economy and budget? Ukrainian bankers should keep this in mind when they channel their clients’ deposits into the Cabinet of Ministers’ default liabilities. They should remember the sad experience of the Cyprus banks that also invested their money into the Greek government’s bonds.

At least 70% of the banks’ resources should be channelled into the economy. However, this is not happening due to the huge risks involved. In terms of the economic risk that includes economic stability, distortions and credit risk, Ukraine’s banking sector has the worst possible rating of 10. Its industry risk is 7. Standard & Poor’s BICRA rates Ukraine’s banking at 9, one of the lowest among all post-USSR states with only Belarus lagging behind with 10.

READ ALSO: Fitch revises Ukraine's outlook to negative

Over the past four months, banks have drawn more deposits than they issued loans to non-financial corporations over sixteen months. Soaring credit interest rates on the one hand and huge risks in lending to the economy on the other have stifled the key function of the banking system, which is to channel free assets drawn from households into the economy. In this situation, banks need to cut their spending to stay afloat. Thus, many banks have already resorted to layoffs and network branch closures. Most of the UAH 2.3bn income the banking sector reported over the past four months came from cutting expenses, namely the reduction of contributions to provisions against operating losses (UAH 2.4bn), rather than the growth of income from lending. Meanwhile, subsidiaries of Western banks are leaving the Ukrainian market because they see no economic prospects of staying in the country.

Economic and industry distortions have accumulated some explosive ingredients in Ukraine’s banking system. The share of bad loans is 20% according to S&P and 35% according to Moody’s. The risk of hryvnia devaluation is pressing the banking sector. The gap between their liabilities and assets in foreign currencies is over UAH 6bn. Devaluation will cause direct losses proportionate to the depth of devaluation and the foreign-currency denominated liability to asset ratio. The intense drawing of free funds from the population and enterprises under huge real deposit rates and the channelling of these into unproductive consumption by the government (through government bonds), consumer or import lending is aggravating Ukraine’s economic crisis and increasing the risk of default of the banks’ liabilities.

READ ALSO: The Eurozone Crisis: What It Means For Ukraine

With this crisis in the economy, industry, banking and other sectors, banks will only be able to resume normal operation if the government’s economic policy changes dramatically, focusing on maximum employment of the population and economic growth boosted with bank lending.