Every year the Finance Ministry answers a number of questions. The key one is: How can we take as much money as possible from the economy? Bureaucrats have argued that this is necessary to meet social needs. The second most important objective is maximising spending on government purchases. The argument is that the budget should not be spent on consumption needs; rather, it has to be used to develop the economy. Next comes increased spending on bureaucrats themselves. This process is usually not discussed openly: money is allocated in seemingly unrelated budget lines and comes through various channels. There is not enough money to satisfy appetites, so some agencies clash fiercely over who gets the bigger share. To them, obtaining a bigger piece of the budget pie means having more influence on society, making the staff more dependent on their decisions and increasing their power. At this point opportunities arise to manipulate things, particularly tax regulations. Bureaucrats know no limits; they do not consider anyone equal to themselves. But these priorities are harmful to the economy.

Maximising money extracted from the real sector is the first and foremost task that goes beyond national markers and borders. Think about the experience of Sweden, France, Italy, Germany and other European countries which embraced social ideas in the 1970s through the 1980s and increased bureaucrats’ financial clout. Their national budgets reached over 50% of their GDP at the time. This led to slower development, unheard-of levels of unemployment and the devaluation of their national currencies. Sweden is often held up as an example of an ideal socialist model, but its GDP fell, the budget deficit reached 13-14% of the GDP and unemployment exploded from 1.5 to 13 per cent for four years running, starting from 1990. All of Western Europe eventually cast off paternalism and did so in a resolute fashion. Nevertheless, the budget models of European states are still more social than those in southeastern Asia or North America.

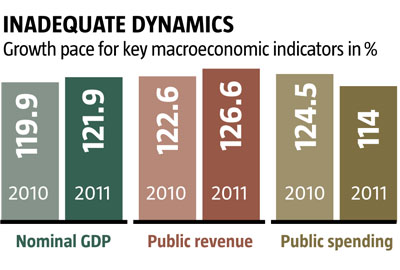

The Ukrainian government is taking money out of the real economy – the receipts of the national budget increased much faster than Ukraine’s GDP in 2010-12 (see Inadequate dynamics). Ways in which the government can fill the budget are well-known: tax receipts and non-tax duties; failure to reimburse of the VAT to exporters; internal and foreign loans (to finance outrageous deficits of national budgets); sale, rent or profitable use of government assets (enterprises, real estate, shares of stock, foreign currency, etc.).

The tax ordeals have already been analysed, but the current leaders crave more. They have continued the policy of taking out extraordinary loans and have driven short-term national debt to unacceptable heights, plunging the state into the so-called debt trap. In 2009-10, the budget deficit amounted to around one-third of its spending, while the total amount of loans obtained by or with the involvement of the government was UAH 100 billion and UAH 140 billion, respectively. Ukraine’s budget deficit was around 9-10 per cent of its GDP in these years, similar to the situation in the USA and France. But Ukraine is not like any of these two countries: they received 2-3 per cent loans that would mature in 15-30 years, while Ukraine took out short-term foreign-currency loans with sky-high interest rates. The example of “older brothers” inspired other countries – hopelessly indebted nations like Greece, Portugal and Ireland – to take anti-crisis measures. They cranked up financing of budget deficits up to 11-14 per cent. The results are well-known.

But ingenious government officials in Ukraine came up with another, more refined way to extract resources for bureaucratic needs. During the 2008 crisis, a law on the Stabilization Fund was passed on the initiative of then president Viktor Yushchenko. This law permitted attracting resources by way of issuing and selling government bonds. These monetary instruments are outside the budget and are used by the government with no need for parliamentary approval. Banks that were nationalised after they went bust during the crisis were found to be useful for these transactions. They sell government bonds and lend financial resources thus attained to contractors working on government-commissioned construction projects or use them to cover the debts of government corporations. The Stabilization Fund is in its essence no different than a budget deficit. Government loans taken out without any supervision are another trick used by bureaucrats to, among other things, underreport the budget deficit. In fact, transactions with money held in this fund contradict the Constitution, but this legal and economic violation persists.

Living on credit leads to a bad ending and paying the interest rates we are paying now is a recipe for disaster. The process started in 2011 and will peak in 2012. Another negative consequence is that most of the loans were provided by Ukrainian banks. So if the government had not obtained them, this money would have gone to the real economy, helping it to grow. Moreover, crediting of enterprises is a process in which financial institutions select the most efficient sectors and projects. It helps carry out structural changes in capital distribution and thus improve the national economy. Now these processes are postponed indefinitely.

There have been also other negative consequences. Under government pressure and in the absence of alternatives financial institutions were forced to set unjustifiably low loan interest rates: 6-7 per cent in hryvnias did not permit them to match the real value of resources. At the time, the NBU’s interest rate fluctuated between 8 and 9.5 per cent, while hryvnia deposits cost no less than 10-11 per cent. Only government-owned banks were eventually forced to issue cheap loans – the NBU supplied them with newly issued hryvnias. As a result, the banking system plunged into a critical condition: a lack of payment instruments propelled the interest rates from 2-4 per cent to 20-30 per cent in two years. On the corporate crediting market, the Cabinet of Ministers drove up the interest rates to 35-40 per cent – something we have not seen in the past decade. A deficit of loans halted the redistribution of capital among sectors and preserved the old structure of the economy, while the extra-high interest rates devoured corporate profits.

Foreign loans have also been overblown – they jumped from $5 billion to $6.2 billion in 2009-10. This money was used to fix the imbalance between the country’s foreign-currency income and expenses. The illusion of a budget surplus was created. In 2010 and the first half of 2011, the NBU reported growing foreign currency reserves. But the government’s excessive appetite for international loans drove up the interest rate on sovereign Eurobonds (up to 11-12 per cent) and blocked access to this market for private Ukrainian companies.

In 2012, Ukraine must pay off the debts it has accumulated, and the volume of excessive (deficit) budget financing has to be greatly reduced. This year, nearly UAH 100 billion (about UAH 90 billion in 2011) must be spent to pay off earlier debts and interest. The Ukrainian government plans to attract new loans in sufficient amounts to finance the payment and servicing of the total national debt. The budget deficit is projected at UAH 45 billion. Thus, the country needs a total of some UAH 140 billion in additional resources. Ukraine is in a fix: sources of financing are lacking; credit ratings are going down; and the debt is growing due to higher interest rates. Ukraine has essentially crossed the critical line after which new loans are not available in volumes that would suffice to pay off and service old debts. As it searches for money, the government cuts the financing of current needs and, as always, revises its social commitments. It is presented as the heroism of power-loving bureaucrats in a hardship, as if the lack of financial resources were generated by objective factors. What can the consequences be? Fiscal bodies will perform more arm-twisting on enterprises and financial institutions, and the banking and credit market will be bled white due to excessive borrowing by the government. Also, the NBU may turn on the money presses if the budget is under-fulfilled, and the expected consequences in terms of inflation will result.

Another utterly harmful way to increase budget receipts is unregulated use of profits generated by government-owned enterprises and the income from their privatization. The government had a burning desire to build stadiums, hotels, airports and highways with budget money. The national budget is not accumulating resources for this purpose, and private funds should have been the source of investment. But, this is not a problem for the current leadership. It took away profits from state-owned companies as if they were their private property and channeled them into projects that the power-wielding clan needs. That these actions undermine the financial condition and harm the companies (and their counterparties) is of no concern to anyone. Ukrtransgaz is a vivid case in point. The company manages the country’s main gas transportation system and secures gas delivery to Europe. It reaps significant profits but cannot, as is known, finance upgrading and fixing the gas transport system, because its profits are used in a non-transparent system arranged for Naftogaz Ukrainy, a company that is formally operating at a loss.

A different principle reigns in privatization: no-one cares about money; government-owned companies are sold for less than half of their value; ownership rights are transferred to the “correct” people. The main thing is for the procedure to be absolutely legal. Undesirable potential bidders are disqualified through specially formulated conditions, and privatization auctions turn into a farce.

This is how they are ruling – fleecing some and giving gifts to others. Moving like a bull in a china shop, they are ruining businesses and squandering finances and social wealth.

The second most important task for bureaucrats is to channel budget money into government purchases by hook or by crook. This is where every minister has things to do. He needs to find the “right” suppliers and contractors and make as much ministerial money flow to them under contracts as possible. Moreover, businessmen have infiltrated government structures, so there is no need to search for anyone: they have their own companies that play solo at one-participant competitions to place government orders.

In 2011, salaries in the education system and health care and ordinary pensions were frozen to fulfil this task. (The government backed down only after government buildings were picketed.) Later, in the second half of 2011, payments to Chornobyl disaster victims, Afghan war veterans and “children of the war” were reduced. It is easy to see that social payments are going to be further curtailed as national budget receipts go down.

What is wrong with bigger volumes of government purchases? Even discounting corruption (which leads to overpriced products and services and wasted budget resources which go into private pockets), these orders are inefficient. Government officials that manage budget money are, by definition, pseudo-customers: they place orders on behalf of the state and pay with money that is not theirs. Thus, the quality of goods and services is usually unacceptable. If the contractor is a government-owned company, the unexacting nature of the customer is multiplied by the irresponsibility of the contractor.

What are the main contractors for the Cabinet of Ministers? These are state-owned companies such as Ukravtodor (received some UAH 9 billion of budget money in 2011), Ukrzaliznytsia (Ukrainian Railway) and other companies managed by the Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure (over UAH 9 billion), companies run by the Ministry of Energy (over UAH 11 billion), and so on. Money flows with little or nothing to show for it. This is not surprising, because part of it fails to be spent on services, and government orders sometimes fail to be fulfilled. And who can control the execution? Ministries and other government agencies? One hand washes the other.

Moreover, there is a trend for government purchases to concentrate in the centre with central government bodies placing orders for increasingly pompous projects. This coincided with Euro 2012 preparations, but megalomania is still there to be seen. Furthermore, not all projects are connected to the football championship. German economist Walter Eucken once noted: “Where a centralised administration is largely in charge of the economy, gigantic investment objects are usually constructed. This was the case in Germany after 1936, in Russia after 1928 and in such dissimilar societies as the Inca Empire … and Ancient Egypt.” The megalomania that devours huge sums of money hampers development by diverting resources away from other social needs. Schools and hospitals are no longer a priority.

Finally, the third objective pursued by bureaucrats is increasing spending on their own official needs and personal welfare. The government keeps setting records in financing its needs: spending on government agencies has been growing at a much higher rate than budget receipts. The power structures – prosecutors’ offices, the police, the security service, the tax administration and the Presidential Administration – lead the pack. (This list does not include lavish decoration of housing and aircraft for top officials.) Despite an existing budget deficit, spending on power structures has been increasing nearly 50 per cent a year. Whence this generosity? What have they done to deserve it, and does it reveal the priorities of the government? Other government agencies – financial, industrial and agricultural –are not far behind. It appears that bureaucrats have sensed that the pendulum of power has swung from democracy to bureaucracy and want to compensate for what they was unable to obtain earlier. Interestingly, spending in public administration offices is going up, but the government claims that the number of government employees and their total pay are being reduced. This may be mere populism, or the government may not want to share with ordinary people of which there is an abundance in the government apparatus.

Thus, the current budget redistribution model can best be characterised in such terms as hyper-centralised, brazen, parasitic and unjustifiably spending-heavy. Unfortunately, it drives out competitive companies by preferring only certain structures and figures. Fundamentally, this is a pro-crisis, deficit-based model which limits, in any macroeconomic conditions, opportunities for productive accumulation of capital, its structural modernization and efficient use.

Structural changes in Ukraine’s budget system that would greatly relieve financial stress and minimise this system’s negative impact on the economy can be summed up as follows:

A lower budget share in the country’s GDP. This means cutting government loans, no delays in VAT compenzation, payment of accumulated VAT arrears, more modest government purchases, no subsidies to unprofitable state-owned companies (including utilities companies and the coal mining industry) and lower expenses on material, technical and social provision for government apparatus members.

The Stabilization Fund, which increases the national debt in a non-transparent way, should be scrapped and the government prohibited from using sovereign loans to pay the debts incurred by state-owned corporations and banks.

A non-deficit budget definitely needs to be adopted. After our trade balance and the balance of payments are fixed, we need to have a surplus budget, which will permit us to gradually pay off foreign debts, give the economy more investment and credit resources and reduce our foreign national debt and expenses on its servicing.

National debt management needs to be optimised, above all, through restructuring our current commitments.

The share of government purchases in budget expenses and Ukraine’s GDP should be reduced by half or two-thirds and later set on the European level of no more than two per cent of the GDP. To this end, the functions of clients and contractors in special industrial, large infrastructure and road construction should be delegated to the private sector. Government monopolies should be divided into 10-15 independent regional companies which ought to be placed in a competitive context. Government purchases of more than one million hryvnias should be placed through a bidding procedure. Competitions need to be held to reduce costs and so on.

Demonopolised state-owned corporations should be privatised through an open procedure by way of selling shares of stock in separate packages at international auctions. Artificial limitations for participants and transfer of controlling interest should be banned. Timely and complete information delivery about privatization processes has to be secured.

The share of spending on government apparatus in the budget should be reduced every year. To this end, regulations need to be introduced that govern their calculation. Government bodies should be stripped of the right to incur capital expenses every year.

Reduced government spending needs to be coupled with several measures in the interests of society. First, less money should to be taken out of market circulation by lowering the budget to 23-24 per cent of GDP. This will permit relieving fiscal pressure and introducing a defined contributed pension system. Second, it is worthwhile to start spending two to three times more on human development: education, science, culture, computer science, health care, environment and the housing and communal services sector all of which are now neglected. Third, a much smaller share of corrupt budget transactions will help reduce social differentiation.

Budget spending cuts in unproductive areas could yield stunning results:

Debt management optimization will reduce expenses from UAH 100 billion to UAH 55-60 billion (which will save 2.7-2.8 per cent of GDP).

With no money going into the Stabilization Fund, the economy will receive at least UAH 25 billion more per annum (1.6 per cent of GDP).

A ban on financing budget deficit with receipts from privatization will yield UAH 10 billion or 0.7 per cent of GDP. Transparent privatization auction procedures will bring another UAH 8-10 billion (0.7 per cent of GDP).

A ban on subsidising unprofitable state-owned and communal enterprises will save up to UAH 40 billion (2.7 per cent of GDP).

Decreased financing of government purchases will free UAH 40-50 billion (3.0-3.8 per cent of GDP).

Less spending on the bureaucratic apparatus will bring UAH 8-10 billion (0.6-0.7 per cent of Ukraine’s projected GDP in 2012).

Thus, the overall savings may reach UAH 190-200 billion (12.7-13.3 per cent of GDP). To compare, total budget spending will be at about UAH 450 billion (29-30 per cent of GDP) in 2012. This means that over 40 per cent of national wealth is now being wasted! Together with financing sovereign debt liabilities, this accounts for nearly 60 per cent of the national budget.