Financial calculations made by government officials show that the budget gap will widen, and the government will try radical methods to close that gap.

According to government data on economic growth, the state and local budgets for 2013 were drawn up based on the nominal GDP of UAH 1.576 trillion and a 4.8% inflation rate. In 2012, budget of all levels were expected to receive UAH 474bn, given the nominal GDP of UAH 1.5 trillion. However, it is evident even now that Ukraine’s GDP for 2012 will not exceed UAH 1.4 trillion. Thus, the budgets are set to receive at least UAH 32 billion less than projected.

According to the government, various-level budgets will account for 29.4% (UAH 463bn) of the GDP in 2013. This means that, adjusted for inflation, the real receipts will drop by UAH 32.2bn. This sum is comparable to two annual budgets of Kyiv and 40 such budgets of cities like Zhytomyr or Sumy. It appears that in order to avoid tackling some hairy issues, the government simply “extended” to 2013 the 2012 state and local budgets which were previously approved but never fulfilled. This means that budget receipts and budget spending will essentially stay at the 2012 level, even though some disbursements will have to be increased, such as salaries in the government sector, utilities for government bodies, pensions, servicing and repaying sovereign debt, etc. Therefore, even if the country’s budgets at all levels receive, in 2013, their respective projected amounts of income (the same as in 2012), they will not rise above the expected 2012 level, which was never reached. Economists call this stagnation.

Therefore, the national finances in 2013 will depend on three key factors which emerged in the second half of 2012: decreasing budget receipts at various levels, issues with financing the Pension Fund, higher servicing costs for sovereign debt due to the replacement of cheap foreign loans (primarily from the IMF) with more expensive money accumulated by selling eurobonds on international financial markets and internal bonds at home.

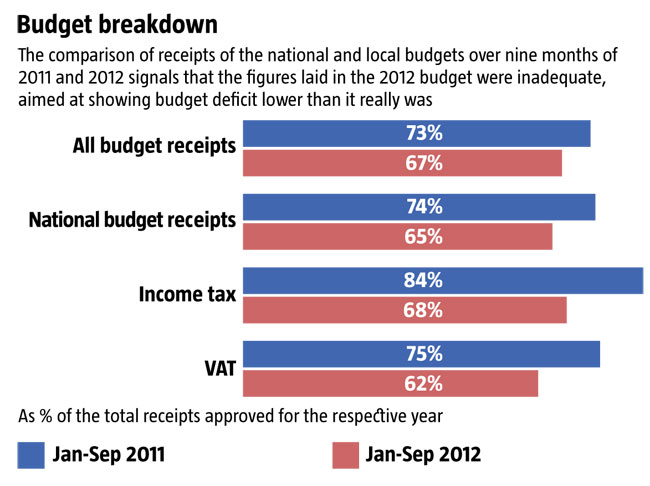

In 2012, there has been a perceptible problem of low state budget receipts (see Budget breakdown) caused by a decline in business activity which, in its turn, is seen as a consequence of crisis phenomena in the economy, deteriorating investment climate and a sharp reduction in loans issued to the real economy.

In January through September 2012, all budgets in Ukraine received a mere 67% of their expected annual income (78% over the same period in 2011). With 65%, the national budget performed even worse. Budget receipts from the income tax were at 68% and from the VAT at 62% over this stretch despite unprecedented pressure the tax administration has been putting on businesses. Clearly, the remaining third is unrealistic to collect in the last three months of the year as has been proved by budget performance in October and November. The reason is the inadequate economic policy and the government’s unwillingness to revise it amid deepening crisis. The national and local budgets were based on the 2012 forecast of 3.9% economic growth (higher than the actual 1.5% in January through October 2012 and possibly close to zero for the entire year) and 7.9% inflation rate (much higher than the actual a 0.3% deflation in the first 10 months). Such government forecasts may have to do with its reluctance to officially acknowledge the worsening budget gap problem and inability to fulfill its financial commitments.

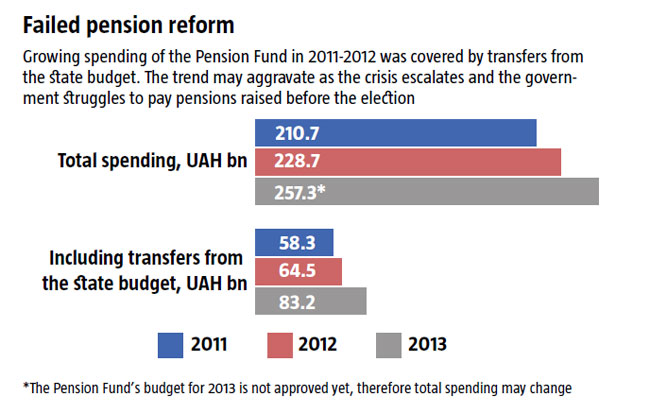

Dangerous trends have been observed in 2012 relating to the Pension Fund gap. In an election campaign boosting effort, the government significantly raised pensions, which cost the Pension Fund an additional UAH 9bn. It failed to collect this sum by the end of the year, so transfers to it from the state budget were increased by nearly UAH 7bn, including UAH 5.6bn in direct financing of the Pension Fund budget deficit (see Failed pension reform). In 2013, a total of UAH 83.2bn will have to be allocated to the Pension Fund from the national budget, which is UAH 17.3bn more than in 2009, the first “post-pension reform” year. Thus, the Ukrainian government is likely to resort, on multiple occasions throughout 2013, to such extravagant moves as a 15% “pension tax” on foreign currency exchange transactions.

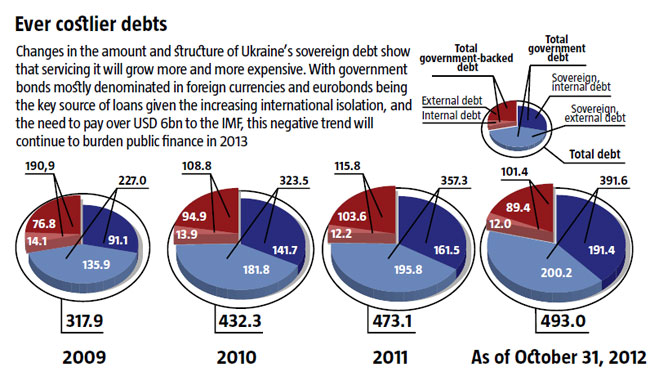

Virtually the only source available to the government to service and repay sovereign debt (and government-guaranteed loans if necessary) is Ukraine’s state budget. The government can make direct disbursements from the budget or use the so-called financing mechanism under which government loans are obtained to pay for outstanding debts. Ukraine’s sovereign debt continues to rise rapidly, increasing by UAH 34.3bn in the first 10 months of 2012, which is equal to about 10% of the state budget receipts projected for 2012. Thus, the Ukrainian government will have a bigger appetite for additional resources next year. It is already planning to borrow UAH 135.5bn, UAH 38.5bn more than planned for 2012. At the same time, the bulk of loans are even now being used to service and repay previously incurred debts, which are becoming increasingly expensive (see Ever costlier debts). For example, in 2012, close to UAH 66bn were used to repay sovereign debt and another UAH 30bn to service it (nearly UAH 96bn in total). In 2013, the respective sums will be UAH 81bn and UAH 35bn, a total of UAH 116bn. This is a significant amount under any circumstances and even more so in crisis time. State budget receipts, the only source for servicing sovereign debt, will be a mere UAH 361.5bn, UAH 12.5bn down from 2012.

Therefore, the state finances will be in dire straits in 2013 due to a number of negative factors which will create tension around formulating and fulfilling the chief functions of the state and local self-government bodies. The declining real budget income and an objective rise in protected spending, such as salary in the government sector, pensions and servicing and repaying sovereign debt, will greatly constrict the room for economic, social and political maneuvers for the government (even to benefit its favourites). In the present situation, financing even these protected articles may turn out to be problematic. Since the key creditor with which the Cabinet of Ministers will have to deal in 2013 is the International Monetary Fund, much will depend on Kyiv’s cooperation with the IMF.

The government is likely to try four different ways to resolve the situation. First, the hryvnia may be devalued through a monetary policy that will stimulate high inflation. The budget will then be essentially filled with devalued hryvnias, thus shifting the economic burden on the population. Second, fiscal and regulatory pressure on business may be stepped up. Third, non-standard ways to close the budget gap, such as a 15% tax on foreign currency exchange transactions, may be introduced. Fourth, budget programmes and social spending may be reduced.