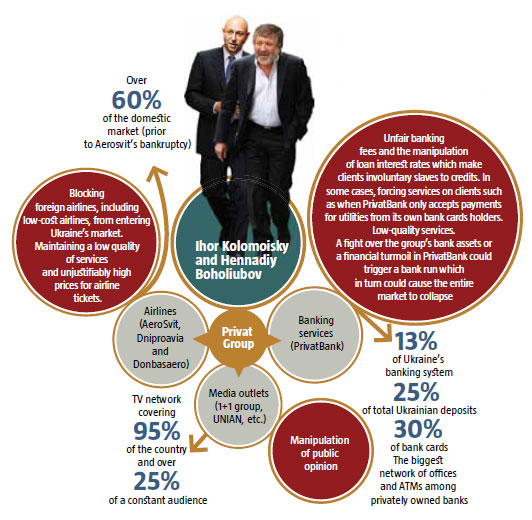

Recent events surrounding AeroSvit airlines and media reports about possible problems faced by PrivatBank have once again drawn attention to the fact that Ukraine’s economy is dependent on a handful of oligarchic groups. On the one hand, the essential monopolization of a series of markets by several structures causes serious problems for consumers and constantly manifests itself in the low quality of goods and services, high prices, delayed modernization and industries falling short of European standards. In this way, Ukraine’s oligarchic economy creates problems for Ukrainians even today. On the other hand, fights over assets between various oligarchic groups threaten to destabilize entire sectors and cause major problems for consumers and, on top of this, pose a threat to the economic and even political stability of the country as a whole. Thus, oligarchs’ problems may quickly turn into problems for most Ukrainians. This abnormal and excessive dependence of the country and its multimillion population on what happens to a handful of families, leads to the conclusion that the oligarchic model itself is the number one problem. If this problem is not solved, the steady and sustained development of Ukraine and its economy is impossible.

THE RIGHT OF THE POWERFUL

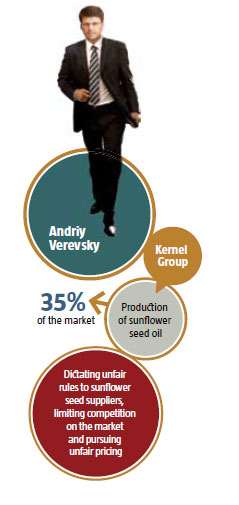

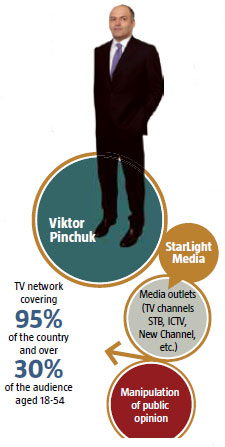

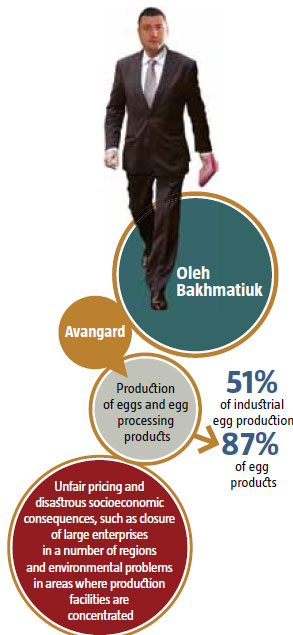

The Antimonopoly Committee recognizes a mere 7.2 per cent of Ukraine’s markets as being monopolized. The Deputy Head of the Antimonopoly Committee, Rafael Kuzmin, said at one point that there were no monopolists among the oligarchs close to the government. In their official statements, major players reject the honorary title of a monopolist and admit to controlling 35% of the market. This is precisely the threshold for declaring a company a monopolist. Such companies hide their other assets behind associated people or offshore structures or simply omit them from their books entirely – Ukraine still does not have a register of monopolists. However, playing hide and seek does nothing to change the real situation – the markets suffer from the high concentration of assets in the hands of oligarchs, which jeopardizes the interests of both citizens and the national economy.

READ ALSO: Government in the Service of Monopolies

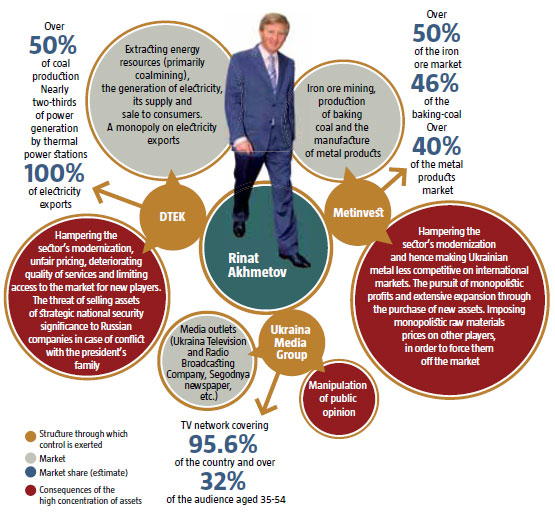

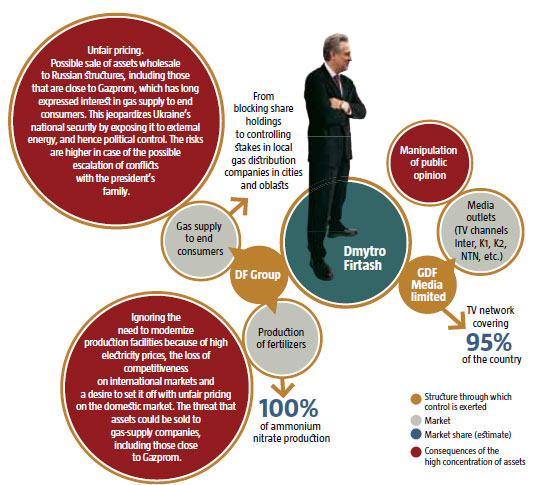

According to the State Statistics Committee, Ukraine’s nominal GDP was UAH 1.4 trillion or USD 175bn in 2012. In comparison, according to public sources, the assets of the top ten Ukrainian oligarchs are valued at USD 33bn. Rinat Akhmetov alone, is worth USD 15.3bn. The core assets of local oligarchs are concentrated in strategic sectors of the economy. And they continue to amass assets. For example, Dmytro Firtash has been actively buying regional gas distribution companies as he seeks to build up his gas supply empire. Akhmetov is pursuing a similar strategy with regional power distribution companies.

The dominant players, equipped with administrative resources and gradually devouring their competitors, do not have the key characteristic of progressive businessmen – the tendency to develop and modernize. For example, countries in the Middle and Far East, particularly China, are among the biggest consumers of Ukrainian metal products. However, China has been engaged in active protectionism in recent times, stimulating its own metallurgical plants to improve their technology and enhance the quality of their products. Meanwhile, Ukrainian metal products are losing competitiveness, partly because of the limited modernization of production facilities. Comparing how much oligarchs spend on bureaucracy, bribes, paid-for rallies, etc. with what they could usefully invest in enhancing the production efficiency of Ukrainian plants, the sad conclusion is that it is cheaper for them to invest in politics than in modernization.

Oligarchs have monopolized markets and have enough leverage to affect government decision-making. Therefore, they block higher quality standards, as was the case with the scheduled transition to Euro-4 and Euro-5 fuel in mid-2012: the transition was postponed indefinitely. Naftogaz Ukrainy and the Privat Group, which control a large share of oil processing facilities in Ukraine, have benefited from this situation, while car owners and enterprises that are forced to buy either expensive foreign fuel or Ukrainian-made products of dubious quality, have suffered.

On the poultry market, monopolism has led, above all, to higher end prices and smaller players being pushed out of the market. Yuriy Kosiuk, owner of the Myronivsky Khliboprodukt Holding, controls about 35% of Ukraine’s poultry market. His main competitor is Yevhen Sihal, owner of Agromax (Havrylivski Kurchata) and Party of Regions MP. The “chicken tycoons” try to establish their dominance on the poultry market in every possible way, such as pushing out independent players and having government regulations changed to gain an advantage. However, the share of imported chicken is growing. According to the Ukrainian Agrarian Association, its share grew from 8% in January-November 2011 to 15% over the same period in 2012. Chicken meat comes largely from the USA and Brazil. The situation with pricing is more than confusing: Brazilian chicken costs about the same as that produced in Ukraine, despite the additional cost of transportation from halfway across the planet.

READ ALSO: Dismantling the Oligarchs' Foundation

Another example of the monopolistic influence is roaming tariffs which remain high for Ukrainian consumers in comparison to the EU, where the so-called maximum European tariff is fixed at EUR 0.29 but is actually EUR 0.13 (UAH 1.3 per minute) in most European countries. Ukrainian subscribers pay many times more per minute. However, one of the most striking examples of joint lobbyism by mobile operators is the delay in the number of practices that have been adopted in developed countries to stimulate competition. The issue of transferring phone numbers across mobile carriers was fixed in telecommunication legislation back in 2009, but this service remains inaccessible to Ukrainians, evidently because it was blocked by the mobile operators themselves.

From time to time, PrivatBank plays nasty tricks on the financial market by exploiting its leverage. For example, in 2011, Ukrainians who had mortgages and were eligible for a tax rebate were shocked to learn that PrivatBank charged about UAH 500 for papers confirming their debt to the bank.

In 2011, Firtash’s company, which had monopolized the fertilizers market, began to unjustifiably raise prices on ammonium nitrate, while farmers had no option but to buy it.

Another illustration of consumer-unfriendly methods used by monopolist companies is the price hike of natural gas for public institutions, which forced them to shell out USD 750-1,100 per m3.

IN A PRECARIOUS POSITION

The fate of large business empires is very closely linked to the lives of millions of citizens and the national economy as a whole. Currently, companies owned by oligarchs are at the centre of foreign-currency flows to Ukraine, sales of Ukrainian goods on foreign markets, pricing, the development of a number of crucial large enterprises and entire sectors in several regions, etc. The main trait of most Ukrainian owners is their desire to concentrate the management of business processes. Asset concentration has reached such a scale that an ownership change can lead to the operations of an enterprise being suspended, goods and financial supply chains being broken, etc. The precarious situation of one monopoly or another will affect the welfare of the country. For example, recent events have shown that when a representative of the president’s Family wants to get a share of a strategic asset owned by an oligarch, an entire sector may be jeopardized. In the future, the stability of the national currency and thousands of jobs may all be at risk.

In hostile corporate takeovers, there are two main scenarios. In the best-case scenario, the new owner takes over strategic assets without significant resistance from the previous owner, who does not have the ability or desire to fight. In a more critical case, he puts up resistance, including through bankruptcy proceedings, the non-payment of salaries and stopping production facilities.

Bankruptcy proceedings launched against AeroSvit airlines in late 2012 stranded thousands of Ukrainians in Ukraine and abroad and exposed the dangers inherent in oligarchs’ fights over assets. Thousands of citizens found themselves at a dead end and a lack of proper reaction caused panic among passengers. Therefore, the redistribution of oligarch-owned property, first and foremost, hurts ordinary citizens and employees who are no longer being paid.

READ ALSO: Taming the Oligarchy

However, there are also examples when asset wars hurt entire sectors. In the spring of 2008, the fight over Volodymyr Matvienko’s assets greatly precipitated the bank crisis. At the time, his Prominvestbank was among the biggest banks in the National Bank classification. Private individuals kept more than UAH 11.9bn on his accounts. In October 2008, the bank began to experience financial difficulties after being targeted by a smear campaign. Almost simultaneously with the onset of the liquidity crisis on the financial market, the National Bank put temporary administration in Prominvestbank, and a chain reaction ensued – problems in other banking institutions, a moratorium on deposit withdrawal, etc. In time, Prominvestbank was sold to the Russian Vnesheconombank.

The elementary fear of losing their assets removes any desire oligarchs may have to develop their businesses, most of which flowed into their hands after the first redistribution of property in the late 1990s. Ukrainian oligarchs do not have any confidence that they will keep their assets in Ukraine in 2-3 years, much less so in 10-20 years. Under conditions of political instability, a ruling class has been formed in Ukraine, which acts on the “grab and run” principle. Thus, money is not being invested in strategic projects, which perpetuate primitive economic models with a low level of competitiveness. Oligarchs invest primarily in sectors which promise quick returns – raw material markets, financial and trade sectors, services, etc.

At first glance, owners who wish to develop their businesses could sell stakes to foreign investors, for example through an IPO, as one of the strategies to protect assets. For example, Kostiantyn Zhevago held an IPO of Ferrexpo (a Poltava-based mining and processing works) on the London Stock Exchange. However, companies close to the Privat Group began to purchase the company’s shares, which triggered a nasty corporate conflict. Fortunately for Zhevago, Ihor Kolomoisky pulled out of Ferrexpo almost immediately after the 2010 presidential election. The lesson is that even an IPO is no guarantee against corporate takeover attempts.

The AeroSvit story has shown that when the president’s Family and figures close to it try to enter any large financial-industrial groups as owners or co-owners or even simply put pressure on them, it may well paralyze one or more economic sectors. To protect their assets, owners resort to direct blackmail, even though it adversely affects consumers or employees. Those who control a large part of a market are able to paralyze it.

Therefore, a situation like AeroSvit’s bankruptcy, could well recur on any market controlled by a Ukrainian oligarch. For example, oligarchs can destabilize the energy market, which they control, as a way to protect themselves. This will have much more catastrophic consequences than the temporary collapse of an airline. The Privat Group controls a large share of the retail oil product market. Akhmetov’s DTEK now secures the generation of more than one-third of electrical energy and over half of charcoal in Ukraine. Firtash’s structures control natural gas distribution in a large part of Ukraine. Chaos in any of these sectors, which are critically important to the normal functioning of the country, could have extremely grave consequences.

The destabilization of Akhmetov’s metallurgical business or Firtash’s chemical business could significantly decrease exports and cut the flow of foreign currency to Ukraine, which could send the hryvnia reeling (the currency crisis of 2008 proves this point.). Equally evident, is the possible collapse of the financial sector if PrivatBank, which accounts for 13% of Ukraine’s entire banking system, runs into problems.

However, one of the biggest risks is that strategic assets, currently controlled by oligarchs, could go to Russian structures under certain political conditions. The latter have been collecting large assets from less successful Ukrainian oligarchs: the Industrial Union of the Donbas (formerly owned by Serhiy Taruta and Vitaliy Haiduk), Prominvestbank, and others. One of the key reasons why Russian capital dominates among foreign capital in Ukraine is the mental and geopolitical factor: Western investors cannot get accustomed to doing business Ukrainian-style. Thus, it is clear that if Ukrainian oligarchs sense their imminent defeat in the competition with their species, they will be able to sell their assets at any moment but only to Russian structures, which have enough skills and clout to keep and protect them in the realities of a post-Soviet Ukraine.

READ ALSO: Why Is Ukraine a Cage for Entrepreneurs?

However, the sale of assets to Russian oligarchs, who already have monopolies in a number of strategic sectors of Ukraine’s economy, will not only mean a loss of economic sovereignty but will also put preconditions in place for them to be used as beachheads from which Russians can work to get other attractive Ukrainian assets under their control and boost the Kremlin’s political influence on Kyiv. For example, Gazprom is interested in gaining access to gas distribution markets (namely the ability to supply gas directly to consumers) as much as or even more than to the transit gas pipeline. For Ukraine, this would mean cementing its gas dependence on Russia and a much greater risk of political blackmail. The Kremlin can reach this objective by purchasing Firtash’s assets. If the oil processing facilities owned by the Privat Group also go to Russian companies, the latter will gradually monopolize this market and exploit it to reap super-high profits and engage in political blackmail. A no lesser threat to national security is a scenario under which Akhmetov’s DTEK is purchased by the Russians. This would essentially mean buying Ukraine’s electrical energy and the coalmining industries at wholesale prices, and these are perhaps the last types of energy for which Ukraine does not have total dependence on Russia.

It is quite feasible to minimize these risks. For one thing, it requires that antimonopoly legislation and the Antimonopoly Committee finally begin functioning. In developed countries, monopolists are, at the very least, fined. This restricts their plans to conquer markets and forces them to invest in innovative technology and venture projects. The influence of dominating companies can be overcome through market liberalization, real control over pricing, improving the business climate, splitting monopolies where possible and having foreign investors buy stakes in monopolies. In any case, the necessary prerequisite for dynamic and sustained economic growth is the fragmentation of oligarchic conglomerates, the liquidation of artificial monopolies and strict government regulation (or even the nationalization) of all natural monopolies. This process should start with the de-oligarchization of political life, the self-organization of the Ukrainian majority into political forces of a new kind – ones that would not depend on oligarchs. They need to be based on diversified financing from such sources as membership fees and the donations of small and medium businesses.