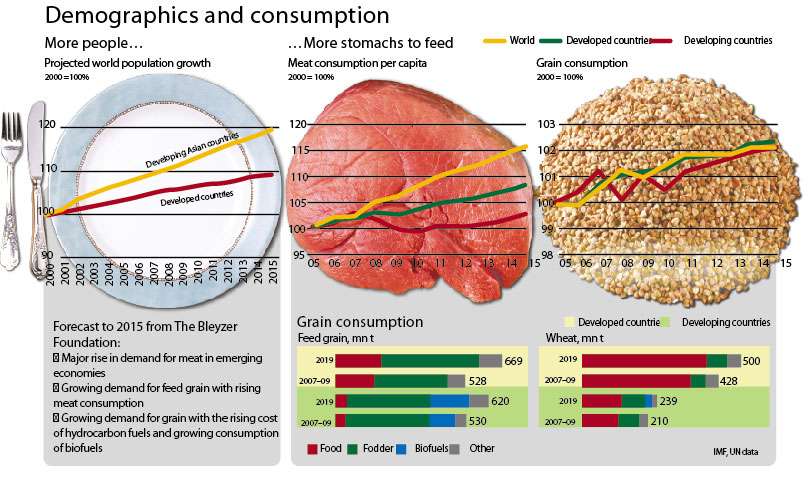

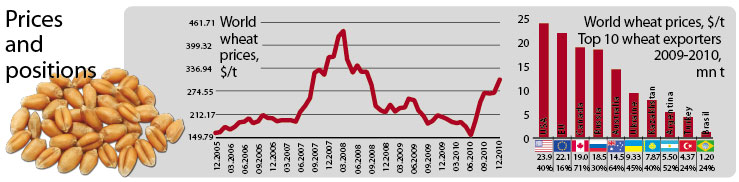

The latest numbers from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) confirm that the Food Price Index of 55 products has been steadily rising for more than eight months now. In January 2011, it had reached 231 points, 3.4% up from December 2010. The grain index hit a peak of 245 points. Over 2010, world prices for wheat skyrocketed 84%, followed by sugar, which surged 55%. These and other disturbing figures spurred talk about a global food crisis—and not without reason (see charts opposite).

For instance, the International Grains Council warns that, at 655mn t, global wheat consumption will exceed production, 651mn t, in the 2010/11 marketing year. Rising demand for food coupled with an unstable financial system, a race to devaluate among the main currencies, and the growing cost of fuels and other raw materials is creating sky-high risks of a food crisis. Prospects are strong that the combination of global devaluation and restricted emissions of currency could lead to a default crisis in many industries, including agriculture. Given that demand is already outstripping supplies by 4mn t in 2011, what a shrinking production of grain could lead to is fairly clear, using wheat is an indicator.

Economics and hot air

Economic theory has already come up with a new term: agflation, meaning the rapid growth of food prices against plummeting supplies as basic inflation remains low and incomes grow nominally for most households. This could lead to a future where growing potatoes will be more profitable than working in an office. Agflation will hit low-income countries and social groups the hardest—those who spend most of their earnings on food.

In Fall 2010, the governments of Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, Indonesia, and Philippines warned that they might run out of some basic foods in 2011. Robert Zoellick, President of the World Bank, called on global leaders to “put food first” among their priorities and “return to a form of gold standard” to prevent global inflation. Available estimates suggest that food production must go up 70% by 2050 to meet the demand of a population expected to hit 9.1bn by then—70% of it urban, compared to today’s 49%.

Among other things, a UN report published at the beginning of June 2010, listed the potential drivers of growing food production for the upcoming decades: Brazil, the Russian Federation, India, China and…Ukraine. Indeed, Ukraine was listed second after Brazil. “We could become part of the global food security program,” Premier Mykola Azarov said at a meeting with Inger Anderson, Vice President of the World Bank. “Ukraine can potentially grow over 100mn t of grain.” So, a global food crisis could turn into a golden opportunity for Ukraine. The catch is whether its Government can foster an environment that can make the most of this glimmering potential.

Practice and reality

In its February 18, 2011 issue, Ukrainskiy Tyzhden wrote that administrative pressure and a growing tax burden are fuelling agflation in Ukraine. So far, this country, with its huge agricultural potential is not only not making the tiniest effort to take advantage of this under the extremely favorable international situation, Ukraine has proved unable to even stabilize its own domestic food market. For instance, prices were officially frozen, but the result was that buckwheat, for one, disappeared from store shelves. To no one’s great surprise, a February survey by the Research&Branding Group showed that most Ukrainians expect a global food crisis to hit Ukraine, too: every third respondent is squirreling away staples.

Trends seen in 2010 confirmed that the ruling party, rather than increasing the potential of Ukraine’s farm industry, including export capacity, or setting up the necessary conditions for any of this, wants to merge Ukrainian farm industry into the existing raw materials monopolies controlled by homeboys or privileged outsiders (see previous article). This offers plenty of space for maneuvering, since Ukrainian and Russian tycoons have shown little interest in agri-business or socio-economic influence over farmland—until now.

The relatively low concentration of production in this sector makes monopolization that much easier. One way is to gain control over two aspects:

pricing policy and sales, primarily exports;

fixed assets and raw materials, including land and fertilizers.

The situation with fertilizers is pretty clear. Most nitrogen companies in Ukraine are already in the hands of Dmytro Firtash and his business empire (see Ukrainskiy Tyzhden #13). Control over the sale of foodstuff is now in the home stretch: Cabinet Bill №8053 contains only two amendments—but very critical ones—to the Law “On supporting agriculture in Ukraine.” In fact, they completely change the system for exporting agricultural products. Ukraine will now have a “state exports agent” selected by the Cabinet of Ministers—via a tender no doubt! This agent may be either state-owned or a commercial entity with a state stake, though the size of that stake is not specified. Art. 16 of the Bill basically grants this agent a monopoly over exports. Its only competitors will be growers themselves, but their exports cannot exceed production volumes. What’s more, this amendment covers exports of wheat, rye, barley, powdered milk, butter, buckwheat and sugar—and the Government can add other items to the list as it chooses. Analysts estimate that the prize is control over annual turnover worth UAH 70 billion, or nearly US $9 billion.

The legislation allowing control over fixed assets including land, firstly, is already drafted. Arts. 19 and 22 of the new Bill “On the land market” establish mechanisms for buying up land from individuals whose farmland is currently being leased for peanuts. If a State Land Fund is established based on a recent initiative, the “privatized” state will get to control all the land in the country that nobody supposedly owns or needs, as well as all the land that the Fund will be able to buy for taxpayer money. Without a proper land market and competition, including foreign investors, the potential of Ukraine’s farm industry cannot be properly developed—especially given the lack of progress in those industries long controlled and exploited by Ukraine’s oligarchs.

Whose top priority?

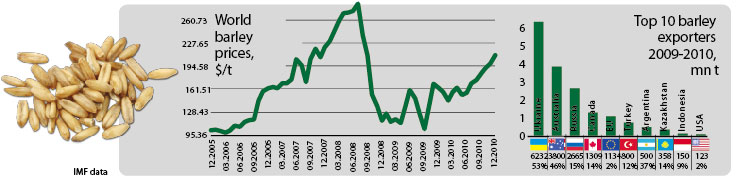

Big Business is most interested in the biggest segment of Ukraine’s farm sector, grains. Over the first six months of 2010, exports in the grain segment were worth US $1,130mn, almost 5% of the total, compared to only US $310mn of exports of dairy products and eggs. In the 2009/10 marketing year, Ukraine was the sixth biggest wheat supplier in the world, shipping 9.33mn t and the biggest exporter of barley, shipping 6.23mn t.

Though official 2010 trading results have not yet been published, it is already clear that the Government changed export policy significantly last year. On October 16, 2010, the Ukrainian Grain Association broke the news that customs officials were blocking ships with grain at all Ukrainian ports. On November 13, Mykola Myrkevych, president of the Association of Farmers and Private Landowners, accused the Government of establishing unjustified exports quotas. He said Ukraine could export up to 16mn t of the 41mn t of grain harvested last year. The UGA estimated the loss to the real sector at UAH 10bn. The government apparently did this to halt inflation on the domestic market and fill its own storehouses with grain at affordable prices. But what does such a policy have in common with promoting Ukraine’s agricultural potential?

The blocking of exports continued even after quotas were distributed among 28 companies on November 12 because the Economy Ministry was holding back licenses. Moreover, the Cabinet cut the timeframe for submitting applications for 2011 export permits in half—from 15 to 7 days after the announcement of registration. In that time, a company would also need to get a confirmation from the Ministry of Agriculture that there was grain available for export. Meanwhile, the practice of giving higher quotas to select companies, a widespread practice in the past, continues.

What happened last fall has important consequences, as businesses linked to the government monopolize food exports. The new political conditions are undermining old market players, who are having trouble meeting their liabilities before foreign partners. At the end of January, Serhiy Stoyanov, President of the Ukrainian Agrarian Confederation, noted that long-time importers of Ukrainian grain keep asking suppliers for long-term contracts. Everyone remembers how the Government suddenly introduced licensed quotas for exports without any transitional period in October 2010. But are any long-term deals possible under the current regulatory policy? Even an inquiry from the Grain and Feed Trade Association (GAFTA) received no response from Ukrainian officials, who withdrew nearly all representatives of NGOs from the commissions in charge of distributing grain quotas, making the process even less transparent.

At the end of December 2010, Agriculture Minister Mykola Prysiazhniuk announced that the Premier had told him to “effectively cancel” quotas by the beginning of February, but that never happened. Could that be because not all market participants have been corralled under an inside operator yet?

An unvarnished conclusion

The medium term prospect is this policy will lead, not so much to the development of Ukraine’s agricultural potential, as to an even deeper fusion of Big Business and Big Government, especially in the farm sector.