About a year ago, The Ukrainian Week wrote about the rise in trade with Russia and the fact that a slew of Ukrainian sectors had grown more, not less, dependent on the Russia market. But at the end of 2018, claims that there was a “sharp increase in bilateral trade” began to be used as a propaganda tool by a variety of politicians who claim to be from the “party of peace.” Indeed, this was the main argument to “prove” that Ukraine could not grow without cooperating with Russia, even with the war, and that it was time to refocus on “traditional markets” once more. The question is, what is really going on in trade between Russia and Ukraine now. We decided to find out.

Which export goods are on the rise and which are declining? What kind of change is there in the dynamic of Ukrainian goods going to Russian markets and Russian goods coming to Ukraine? What kind of impact on the impression of “steep growth” in trade volumes with the enemy has the fact that prices for energy and raw materials have sharply gone up had, given that these commodities traditionally dominated in Ukrainian imports from the Russian Federation and have lately taken over a growing share of those imports?

A continuing decline

Exports of Ukrainian goods to the RF hit the bottom, US $3.59bn, in 2016, which was about one sixth of what it had been at its peak in 2011, US $19.80bn. In 2017, a correctional rollback could be seen: although the share of trade with Russia, now at 9.1%, continues to shrink, the actual value of these exports has risen to US $3.94bn. Moreover, this adjustment did not alter the underlying dynamic and quickly faded. In 2018, trade continued to be curtailed: according to the State Fiscal Services actual data on customs statistics, exports of domestic goods to Russia fell 7.7% from 2017 to 2018, bringing in US $3.65bn, very close to what it had been in 2016.

Just about the only major item in Ukraine’s exports to Russia that showed growth in deliveries in 2018 was alumina from the Mykolayiv Aluminum Plant, which is in fact a subsidiary of the vertically integrated Russian company Rusal, founded by Roman Abramovich and run by CEO Oleg Deripaska. The value of these exports grew 9.2%, from US $392mn to US $428mn. However, the volumes barely changed in the first 10 months of 2018 compared to the first 10 months of 2017: 1.40mn t vs 1.37mn t. The reason for the growth in value was a rise in the global price for a tonne of alumina from US $286 to $307.

The biggest items in Ukraine’s exports to the Russian Federation remain domestic machinery and equipment. For the first 10 months of 2018, they accounted for nearly 27.0% of all domestic exports to Russia. At this point, however, they amount to a mere shadow of their former multi-billion dollar turnover. As before, absolute numbers in most positions have been in a steady decline, even as the cost of a unit has gone up.

Derzhstat data for this period shows that, compared to the same period of 2017, the only growth has been in deliveries of electrical equipment, up 18.0%. Exports of ships and related items shrank another 7.8%, exports of locomotive engines were down 10.3%, optical instruments and apparatuses were down 20.9%, other heavy machinery – mostly mechanical and industrial equipment – was down 21.6%, vehicles and spare parts were down 30.0%, and deliveries of aircraft and parts have pretty much stopped.

As before, nearly a quarter of Ukraine’s exports to the RF remain ferrous metals and steel products, posting at 23.8% in the first 10 months of 2018. But overall volumes have also fallen: ferrous metals are down 9.0% and steel products are down 6.6%. Moreover, this has happened despite a substantial increase in prices for the main types of Ukrainian-made steel products that are shipped to Russia. For instance, uncoated hot rolled carbon steel sheet over 0.6 m wide was up on average at US $555/t in 2018 compared to US $484 in 2017, while cold-rolled product was up at US $562 vs US $534, coated product was up at US $667 vs US $567, and so on.

RELATED ARTICLE: Start with China

It appears, then, that the decline in trade among Ukrainian suppliers is the result of volumes shrinking faster than prices are rising – in some cases 50% and more. Shipments of coated steel product shrank from 108,500 t in 2017 to 71,700 t in the same period of 2008, while deliveries of angles and other profiled steel went from 314,100 t in 2017 to 184,600 t in 2018. The price for one tonne of seamless steel piping jumped from US $1,036 in 2017 to US $1,540 in 2018, but export volumes to Russia were down from 70,000 t in 2017 to 47,700 t in 2018.

In short, the volume of deliveries of Ukraine’s main export commodities to Russia not only has not grown, but has for the most part declined significantly in the last year. The main exports that bucked this trend were mainly secondary product groups (see Bucking trends) whose share of overall Ukrainian deliveries to Russia and of production volumes in their respective sectors is not significant.

All told, 2018 saw a further reduction in the dependence of Ukrainian manufacturers on Russian markets. Of course, some diehards continue to play Russian roulette, focusing on an uncertain market in a country with which Ukraine is at war. They could find themselves holding the short end of the stick if trade is officially stopped. However, the current volumes of trade do not represent a serious threat to the domestic economy as a whole, and so it comes down to a matter of private risk as business owners.

The nature of Russian imports

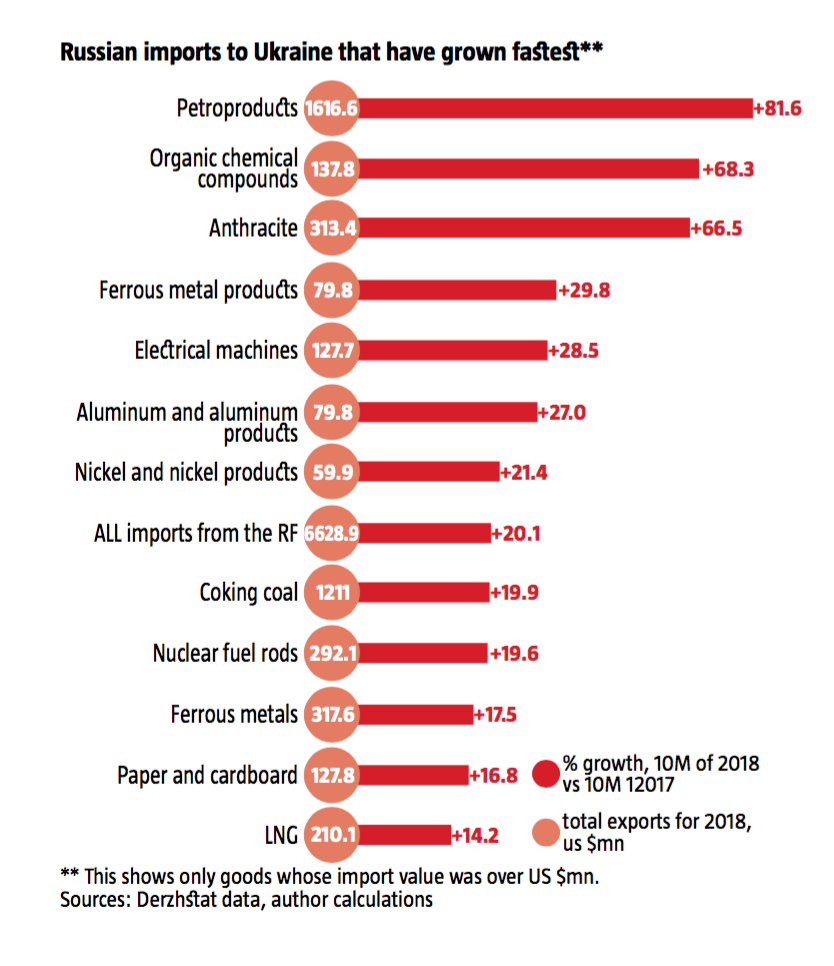

In contrast to Ukraine’s exports to Russia, Russian imports to Ukraine continued to grow strongly in terms of value, reaching US $8.1bn, which was almost 60% up from its low point in 2016. This trend is about to end. Whereas in 2017, Russian deliveries to Ukraine grew over US $2bn, in 2018 they grew only US $0.9bn. Moreover imports from all other countries to Ukraine are growing at a much faster pace, so the share of Russian imports is also slowly shrinking, from 14.6% in 2017 to 14.2% in 2018. The same is happening with the share of exports of Ukrainian goods to the RF.

Once again, a more detailed look at Russian imports to Ukraine shows that there, too, most goods are rising not in volumes but simply because prices per unit have gone up (see charts). The exception is energy, where growing dependence is really reaching a dangerous scale.

The most noticeable contribution to the growth of Russian imports was petroleum products, coking coal and anthracite. If we leave these three items out, Russian imports were actually down in 2018 compared to 2017. Although total deliveries of Russian goods to Ukraine grew US $0.9bn, petroleum products accounted for more than US $0.7bn of that and were up nearly double, from US $890.1mn to $1,616.57mn. This was because the cost of a tonne was up nearly 33% and volumes grew from 1.8mn t to 2.5mn t. The result was that the already extremely high share of Russian supplies of petroleum products grew even more noticeably: fully 38.4% of all such imports came from the RF. If Belarus is added, since it effectively exports Russian products, then Russian petroleum products account for nearly 80% of all such imports.

Second place for increased value of imports from the RF goes to coking coal, the raw material for preparing metallurgical coke, which is a critically important fuel for the domestic steel industry. Imports grew US $200mn, from US $1.01bn to US $1.21bn while the price remained almost unchanged, going from US $122.80/t to US $127.00/t. Meanwhile deliveries of ready met coke went down from 608,000 t to 505,000 t and its price also did not change. However, the share of Russian imports of coke to Ukraine jumped to 69% because alternative deliveries from Poland collapsed from 474,000 t in 2017 to 62,300 t in 2018.

Ukraine’s economy has also grown more dependent on anthracite from Russia. For the first 10 months of 2018, 2,920,000 t were delivered for US $313.4mn when during the same period of 2017 only 1,880,000 t worth US $184.24mn were delivered. What’s more, alternate deliveries from South Africa have also collapsed, from 456,000 t to 118,900 t, even though the price from RSA is US $101.80/t, while the price from RF is US $107.30.

Imports of nuclear fuel from Russia for Ukraine’s AESs also grew from US $244mn to US $292mn. Not long ago, the press reported that the contract for these deliveries was secretly prolonged. Meanwhile, procurements of alternate fuel rods from Westinghouse slipped from US $137mn to US $121mn, despite assurances from the Cabinet that the share of US fuel was supposed to be increased while Rosatom’s was to be cut. It’s clear that lately the diversification of nuclear fuel suppliers has been put on hold – as well as efforts to reduce Ukraine’s dependence on Russian anthracite.

Meanwhile, some types of Russian energy raw materials are slowly being squeezed out by American ones. Although an overly large share of all imported coking coal still comes from Russia (9,550,000 t of a total of 14,060,000 t), volumes have actually grown 16.1%. But imports from the US and Canada grew 42.8% from 2,920,000 t in 2017 to 4,170,000 t in 2018 as the price for quality American materials went don 6.7%/ t, in contrast to Russian prices, which went up more than 3%. Alternative deliveries of met coke from the US grew sharply to 79,700 t in 2018 from nothing in 2017, as did deliveries from Colombia, which were up from 28,600 t in 2017 to 49,400 t in 2018, thanks to the much cheaper cost of coke from those two countries: the US price was US $311/t.

Meanwhile Ukraine’s supposed growing dependence in 2018 on deliveries of a slew of strategic energy resources from Russia under other items turned out to be mostly caused by higher prices in 2018. This was the case with Russian deliveries of LNG, which grew in value because the unit price jumped from US $396 to US $498, while volumes actually declined from 465,000 t to 421,000 t.

The same is true of Russian deliveries of hot rolled sheet steel, where the value went from US $60.9mn to US $65.3mn because the price per ton went from US $535 to US $602, while deliveries contracted from 113,800 t to 108,400 t. This was also the case with unprocessed aluminum, where the same volumes were delivered both years, but the cost rose from US $2,150 to US $2,400/t. Similarly, the value of nickel imports went up nearly 50% although the volumes shipped from Russia remained the same.

What’s coming?

It seems that the short-term corrective growth in trade with Russia that was especially pronounced in 2017 is rapidly coming to an end. Ukrainian suppliers are dropping Russian markets faster than Russian ones are dropping Ukraine. Still, the growth that did take place was mostly the result of significant rises in commodity prices, while physical volumes grew only in exceptional cases. With the exception of a number of genuinely vulnerable sectors that represent a potential security threat for Ukraine, interactions between the two countries’ economies continue to go down.

Notably, Ukraine’s economy is in recovery mode, especially in the “growth belt” connected primarily to positive trends over recent years with the country’s EU neighbors. Meanwhile, the economic situation in the RF has grown steadily worse over 2014-2018, with 2017 GDP actually 0.6% smaller than in 2013. Since early 2018, Russia’s economy is also growing half as fast as Ukraine’s: according to Rosstat, H118 saw only 1.6% growth, whereas Ukraine’s GDP grew 3.4% and neighboring EU countries saw 4-5% growth.

This suggests that exports from Ukraine to the RF have fallen off less because of mutual sanctions and the war, than because of Russia’s own domestic economic problems. Rosstat reports that total imports to Russia fell from US $315bn in 2013 to US $227bn in 2017 and only grew 7.3% in the first 10 months of 2018. Those Ukrainian companies, sectors and regions that have not so successfully shifted to other markets have been suffering and will continue to suffer even more.

RELATED ARTICLE: Exports: A successful shift

Where Ukraine needs urgent and decisive state intervention is in the risky trend towards growing dependence on Russia for critical imports of petroleum products, LNG, anthracite, and coking coal. Moscow has shown more than once that it is very happy to take advantage of any weakness in its hybrid war against Ukraine. Examples include the crisis on the gasoline market in 2017, interruptions to deliveries of anthracite including fall 2018 for the Ladyzhynska TES, a key co-generation plant in Vinnytsia Oblast, which nearly caused the entire system to come to a standstill. The government still doesn’t seem to have drawn the necessary conclusions.

Moreover, those in power seem to be criminally inactive and even playing up the situation. Possibly it’s for the mercantile reasons of those at the top. Back in April 2017, MinEnergo submitted a draft resolution to the Cabinet to ban the import of heating coal from Russia, but the Government to this day has not approved the necessary decision. Later on, the Anti-Monopoly Committee blocked a decision intended to restrict the use of Russian anthracite in favor of using gas coal, which is extracted in Ukraine – without any appropriate response on the part of the higher ups.

With no proper response from the National Security Council or the Presidential Administration, Russian imports continue to completely dominate Ukraine’s petroleum product, LNG, coking coal, and non-ferrous metals markets. What’s more, the complete dependence on the Kremlin of the Russian business groups that control these deliveries and how easily this could be used in the hybrid war against Ukraine are completely being ignored. Should Russia stop delivering most of these goods, most of them can be found through other suppliers. However, when Ukraine is dependent 60-80% on deliveries from Russia, this is not something that can be done quickly. So preparations need to start today.

The path to resolving this problem is pretty obvious. All the Russian deliveries of strategic energy resources and industrial raw materials that could be stopped on a dime for political reasons constitute a serious threat to Ukraine’s national security: they can paralyze or disrupt stable energy supplies to Ukraine’s households and industries, and stop operations in major industrial sectors. This means that restrictions must be placed on the import of these critical items from Russia, to a maximum of 25-30%. In the meantime, the real, not nominal, source of imports must be taken into account. For instance it’s obvious that petroleum products and LNG from Belarus should be treated as imported from Russia, which is the sole source of all raw materials for its neighbors manufacturers.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook