On September 16, it was four years since Ukraine ratified its Agreement on Association with the European Union. It’s also nearly three years since the economic section on the deep and comprehensive free trade area kicked in at the beginning of 2016. Meanwhile, this entire time — and even more so now that the 2019 election year is on the horizon — retrograde forces in Ukraine have been persistently and consistently putting it out in the domestic press that the country’s economic shift towards the EU and the loss of supposedly traditional post-soviet markets — read the Russian Federation and its satellites — has supposedly had a catastrophic impact on Ukraine’s economy and its growth prospects. Unfortunately, skepticism about the competitiveness of “Made in Ukraine” products on European markets and tired clichés about nobody wanting Ukrainian goods with high added value there are also fairly common among those who have persistently and consistently been against any return to Russia’s orbit.

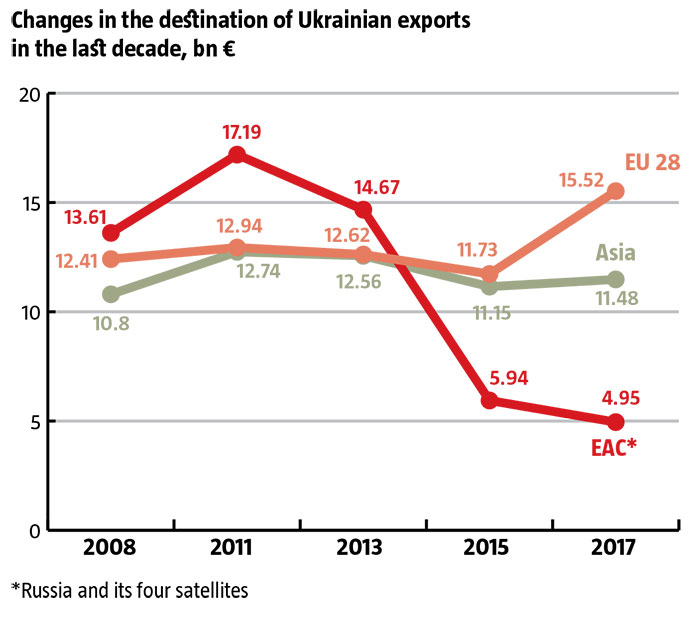

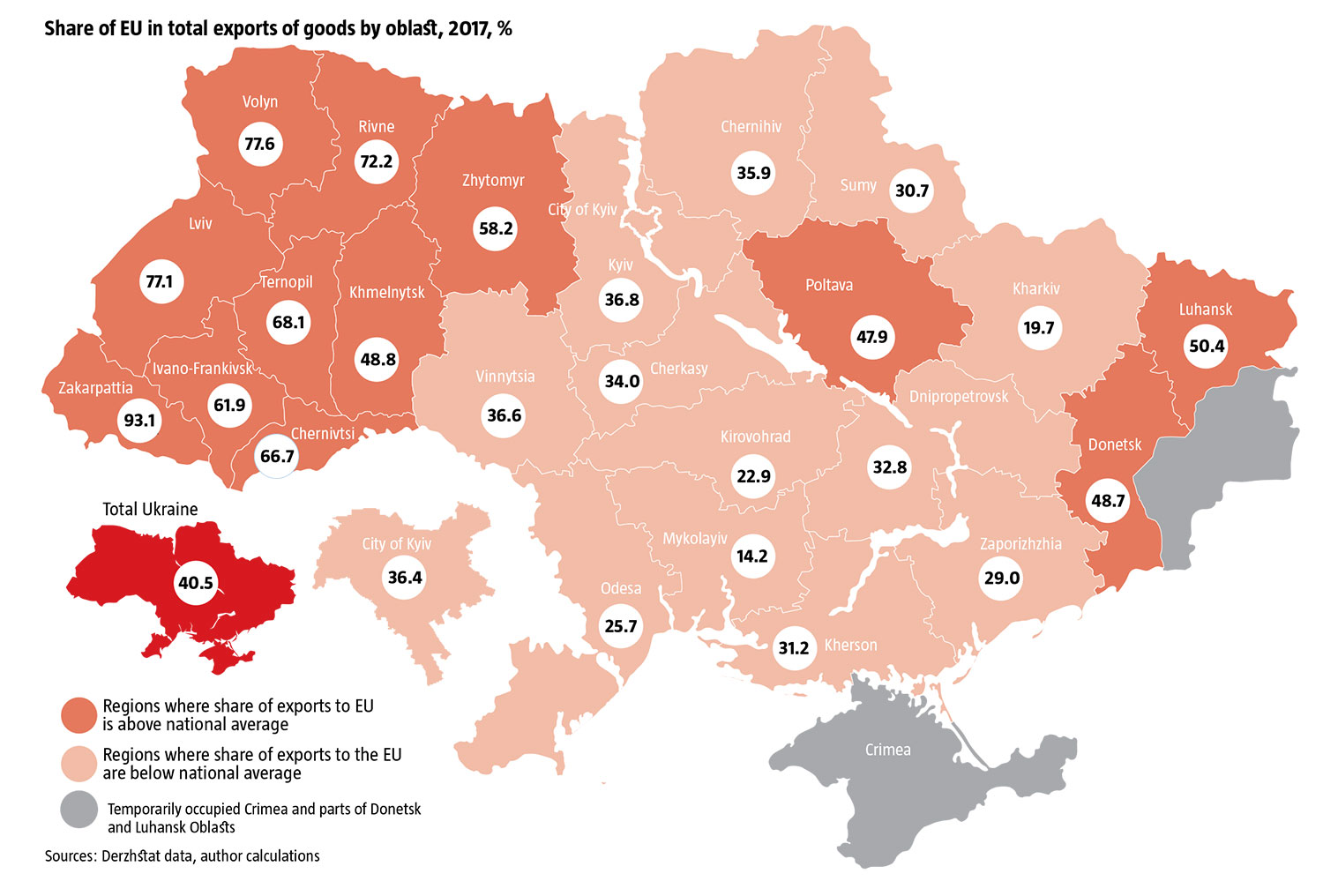

The actual dynamics of bilateral trade with the EU I recent years paint a completely different picture, especially regarding the growth of sales to EU countries. Exports to the EU hit their peak last year, when they passed the €15.5 billion mark. And they keep on rising. For the first eight months of 2018, they are up another 18.6% according to the State Fiscal Service. Their share of total exports has also gone up from 40.0% to 42.1%. Indeed, in 12 of the 25 non-occupied regions of Ukraine, exports to the EU are between 50% and 90% of total exports. What’s more, this is true not only of traditionally Europe-oriented western Ukraine, but also easternmost Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts, where exports to the EU also account for 50.0% of all exports and are higher than many regions in central Ukraine.

Overall, Ukraine’s exports, including to other parts of the world, are largely well below, and even severalfold below, their previous peaks in 2008 or 2013. This demonstrates just how significant Ukraine’s reorientation on EU markets has been in the last few years (see charts).

Of course, these trends in bilateral trade since the AA and DCFTA came into effect are bringing more benefits to Ukraine than to the EU. Fears that Ukraine’s supposedly unprotected market will be flooded with European goods appeared completely groundless. The reality is quite different: Ukrainian exports to the EU grew from €12.62bn in 2013 to €15.52bn in 2017, an increase of 23.0%. Meanwhile, EU imports to Ukraine contracted by 9.6%, falling from €20.36bn to €18.41bn over the same period — and this despite the fact that reverse deliveries of natural gas, worth €0.64bn in 2013, nearly tripled to €1.70bn in 2017. If gas is taken out of the equation, then the balance of trade deficit for Ukraine fell from €7.1bn in 2013 to less than €1.2bn last year. What’s even more impressive is that the strongest growth in Ukrainian exports to the EU was not in raw materials but in finished products and parts, including for machine-building.

RELATED ARTICLE: System recovered. Now back it up

It seems, then, that the real threat is that Ukrainian manufacturers are succeeding on the European market and Ukraine’s economy is reorienting towards the EU once and for all. Hence the very active bombardment of negative statements about the lack of prospects for “Made in Ukraine” in the domestic press. Because this clear and growing success — inevitable difficulties with growing market share notwithstanding — will put an end to nostalgia over the mythical “lost paradise” on the “salutary” Russian and post-soviet markets whose purpose is to discourage potential domestic exporters who have not found the courage or opportunity to investigate niches on the EU market as well as the general public. The longer the opposite is proved, the sooner the arguments of those who favor the “inevitable return to traditional markets” will lose any sense whatsoever.

Facts are stubborn things

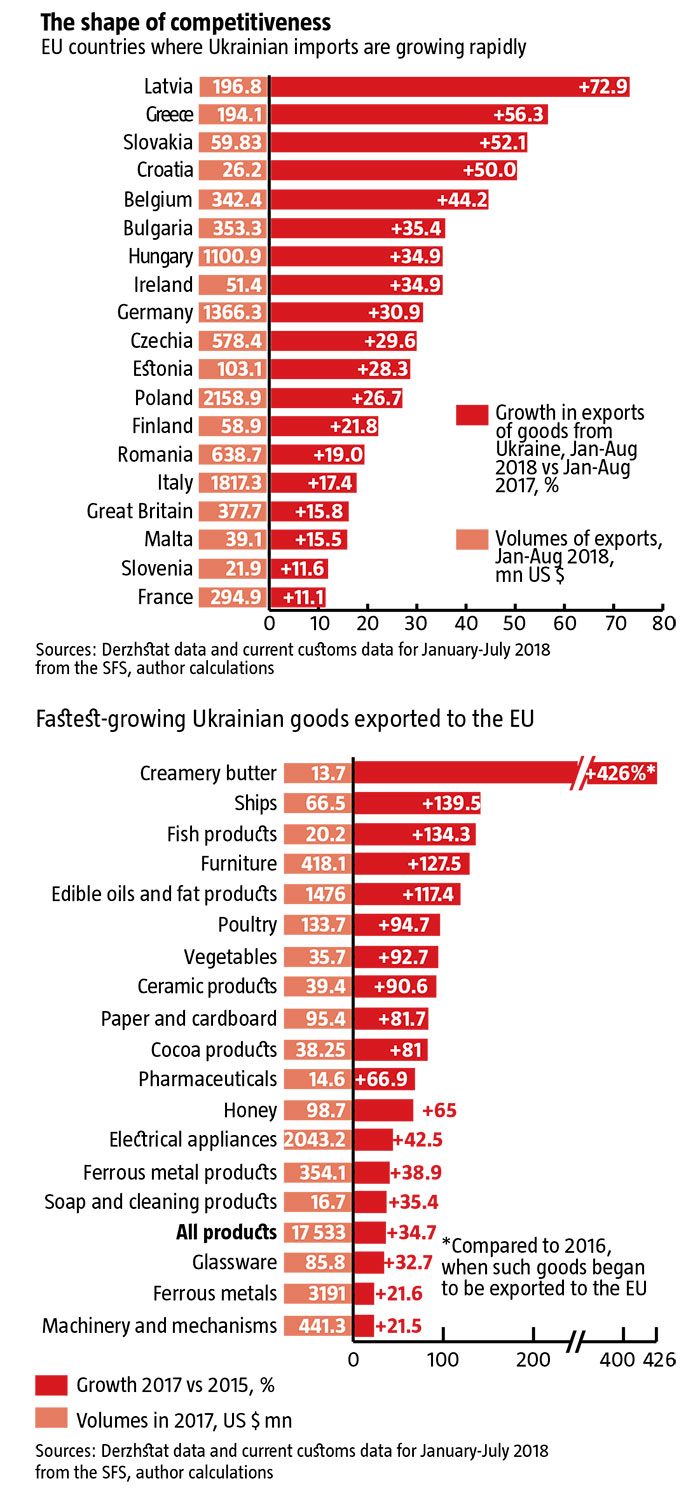

A cross-section of the kinds of goods that have been exported to the European Union in recent years gives a pretty good picture of the direction Ukraine’s export is developing in. For instance, in 2015, just before the economic section of the Association Agreement and DCFTA with the EU kicked in on Jan. 1, 2016, can be compared to 2017, which is the last full year for which export data is available. In individual cases, the most current trends can be seen from the figures offered by the State Fiscal Service (SFS) for trade over January–August 2018.

In particular, three branches of machine-building sector have seen significant growth in exports to the EU: electrical engineering, shipbuilding and the manufacture of machinery and mechanisms. The sharpest growth has been in shipbuilding, where exports to the EU grew 140%, from to $66.5mn in 2017. The most striking improvement in absolute terms was in electrical engineering, whose export sales grew from US $1.40bn in 2015 to US $2.04bn in 107, an increase of 45.7%. Despite talk about the EU needing nothing from Ukraine but raw materials, the overall export of equipment and machinery to EU countries in 2017 was US $2.70bn, a 15.3% share of all goods exported to the EU, compared to a 11.6% share of such products in Ukraine’s exports globally.

The same can be seen in metallurgy and chemicals. A closer look shows that finished Ukrainian goods with a higher added value are having an easier time breaking into EU markets than half-finished goods with a lower added value. For instance, ferrous metal products grew 38.9% from 2015 to 2017, but ferrous metals themselves and semi-finished goods only grew 21.6%. Exports of fertilizers from Ukraine to the EU dropped by nearly 67% from 2015 to 2017, while non-organic chemical products fell 20.4%. By contrast, deliveries of Ukrainian chemical products with higher added value and greater energy efficiency have been growing: pharmaceuticals have leaped 66.9%, plastics, polymers and products made of them have jumped over 53.0%, and soaps and detergents have gone up 35.0%.

Exports of Ukrainian-made furniture to the EU have skyrocketed nearly 130% in just two years, and were worth over US $418mn in 2017. Lately, more than UAH 1bn in furniture made in Ukraine is being delivered to the EU every month. Trends for other finished manufactured goods are also showing very positive growth: ceramic products have increased to US $144.1mn, up 90.6% over the last two years; paper and carton have risen 81.7% to US $95.4mn; and glassware has risen 32.7% to US $85.8mn. The list goes on.

Food exports are no exception. Low-added value products are slowly losing their positions, with grain exports growing only 5.0% from US $1.63bn in 2015 to US $1.72bn in 2017. Deliveries of food processing wastes and other food used for fodder inched up from US $490.0mn in 2015 to $500.0mn in 2017. Meanwhile, sales of fresh fruit and products made from them have gone up 14.7%, to US $126mn, and sales of honey have jumped 65.0% to US $98.7mn.

Although MHP owner and billionaire Yuriy Kosiuk has complained publicly about low quotas, exports of Ukrainian poultry to the EU skyrocketed 94.0% over 2015-2017. In fact, the EU accounted for 34.3% of all the earnings from exports of Ukrainian poultry worldwide — US $133.7mn. Exports of creamery butter began in 2016 and have been growing sharply, from US $2.6mn the first year to US $13.7mn by the end of 2017, and were already at US $7.6mn by mid-2018. Yet, until not long ago, dairy products also seemed to not have a place on EU markets. From 2015 to 2017, exports of edible oils and other fats jumped 120%, to US $1.48bn.

None of this is to deny that, in fact, Ukrainian exports to the EU continue to be based too much on raw materials and semi-finished products with a low added value. Still, this is less a problem of trade with the EU but the nature of Ukraine’s overall economy and exports. Indeed, the growing shift in Ukraine’s exports to the EU and general trends suggest that European integration is actually helping the country to move away from being primarily a source of raw materials. Besides, a large and wealthy market like the EU is the best incentive for domestic SMEs that are focused on producing goods with a higher added value to develop and expand. Working with distant and often very peculiar markets in doing business with Asia and Africa, not to mention South America, suits Ukraine’s big, generally oligarch-owned businesses. But they continue to largely exploit the country’s raw materials potential or else are openly developing their own strategy for deliveries outside the home market, because semi-finished goods are what their outdated decades-old — sometimes even a century old — factories can readily produce.

Looking at prospects

The AA and the reorientation of Ukraine’s economy towards EU markets is not the reason why the country’s exports continue to be dominated by raw materials and semi-finished products: this is what the country inherited from soviet days and has not managed to ameliorate. On the contrary, European integration is spurring the trend towards finished goods and a reduction in the share of commodities with low added value. The possibilities are enormous and the share of EU exports, which reached 42% in the first 8 months of 2018, could easily become greater. To gain even a few percentage points of market share in EU imports means to increase deliveries from Ukraine severalfold.

Moreover, there are plenty of niches in European markets where no domestic business has a presence, but very well could. So far, even though the EU is the country’s biggest trading partner, the volumes and types of Ukrainian goods that are delivered to bigger and wealthier EU members like France or Great Britain are still several times less than what the country sells to much smaller and poorer Moldova and Georgia. What’s more, Ukrainian exports to the economic core of the EU (Germany, France, Benelux and the UK), which represents more than half of its economic power and over 45% of its population, remain considerably less than exports to the Visegrad Four with their far weaker economies.

Exports to the biggest European countries also remain narrow profiled and co-production is still nascent, although this form of cooperation is common in the lion’s share of bilateral trade within the EU and proved to be the catalyst for economic integration into the Union for the most successful post-socialist economies. By contrast, Ukraine enjoys a substantial trade relationship only with Germany and the Visegrad Four.

All the complaints about nobody wanting “Made in Ukraine” is simply an indicator of how little willingness to change and flexibility there is among pro-Russian businesses. Those businesses that want to and make an effort are gradually finding opportunities and a place for themselves on different markets, without necessarily even competing head-on with European companies. Sometimes just competing with corporations outside the EU is enough. Deliveries to the EU have quotas and restrictions, but these are generally aimed at those very raw materials about which Ukraine’s fifth column so likes to make noise. Indeed, trade conditions with the EU are making it difficult for Ukraine to continue to be predominantly raw materials based and easier for the country to focus more on finished products.

RELATED ARTICLE: Not bad, but could be better

Slowly but surely, Ukraine is integrating into the production cycles of major transnational corporations. Hopefully, this practice will be expanded to the entire country in the nearest future, including the southeast, which is seeing the demise of its obsolete manufacturing sector. This is where entering European markets is putting pressure on the passive management of many companies that, until not long ago, were only focused on “traditional” post-soviet markets.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook