As previously projected by The Ukrainian Week, Russia is playing hardball to keep Ukraine out of the Association Agreement and FTA with the EU (see Caught in a Zeitnot). Talks on this issue between presidents Yanukovych and Putin and premiers Azarov and Medvedev have so far proven fruitless, while the official declarations of both countries that “there can be no trade wars between Ukraine and the Russian Federation in principle” merely cause confusion. However, they fail to hide the discrepancies between the pacifying statements and the worrisome reality. For instance, Vice Premier Yuriy Boyko, who chairs the Ukrainian working group allegedly set up to solve the troubles on the Ukrainian-Russian border, said on August 17 that most issues with Ukrainian goods stuck on the Russian border in cargo trains will soon be solved. However, more and more Ukrainian entrepreneurs are suspending exports altogether to avoid their goods being held up by customs officials for unlimited periods.

READ ALSO: Transit to Asiope

Meanwhile, the trade war is a hot topic in both the Russian-sponsored and a number of Ukrainian media, painting apocalyptic scenarios for Ukraine if Russia continues to block Ukrainian goods. By doing so, they are playing into the hands of its spin doctors whose aim is to persuade Ukrainians that the Russian and Customs Union (CU) markets are more important to Ukraine than European ones, and that Ukraine’s economy will not survive their loss. The most proactive promoters of this message include Sergey Glazyev, Advisor to Russia’s President for regional economic integration, and the father of Putin’s goddaughter, Viktor Medvedchuk. The latter has stated that “Ukraine has to understand that sooner or later, the Customs Union will implement protective measures if Ukraine opts for the Association Agreement rather than the Customs Union.” According to Glazyev, “this test was of a one-time nature… but we are preparing to tighten customs procedures if Ukraine should suddenly take the suicidal step of signing the EU Association Agreement.”

European officials do not hide their concern over Russia’s actions. The European Commission represented by Commissioner for Trade John Clancy called on “both sides to settle their differences within the WTO” and expressed the expectation that the EU’s trade concerns with both Russia and the Ukraine” are to be solved swiftly and in the “spirit” of WTO commitments. Moreover, some in the EU claim that it is not about the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, but about Moscow challenging the EU, as it is pushing Ukraine not to sign the Association Agreement. On August 28, the Committee on Foreign Affairs will hold a special extraordinary meeting. According to its Chairman, Elmar Brok, it is going to assess the political impact of Russia’s latest threats, should Ukraine sign the abovementioned document. A joint statement by a group of parties in the Euronest (EU and Eastern Partnership) Parliamentary Assembly, chaired by Jacek Saryusz-Wolski, claimed that the EU, as an interested party in the conflict, should act to protect Ukraine from Russia’s actions since they are hostile to both Ukraine and the EU.

Hannes Swoboda, President of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats group, joined his colleagues by saying that “Ukraine should have full independence to decide its foreign policy…it must have the right – without any external pressure – to enhance its relationship with the EU. And the EU must support Ukraine's ambition for closer ties.”

FEAR HAS BIG EYES

Attempts to intimidate Ukraine with trade warfare stem from a stereotype, whereby Russia is Ukraine’s most important economic partner and staying out of the CU will undermine Ukraine’s economy. This stereotype was established in the 1990s when Ukraine’s economic dependence on Russia, inherited from the USSR, was indeed significant. Now, its extent is greatly inflated.

Concerns are fuelled by overblown estimates of Ukraine’s potential losses, while the risks for Russia if Ukraine resolves to respond are overlooked. For instance, estimates of the possible decline of Ukraine’s GDP as a result of lower exports to Russia are exaggerated. They overlook the fact that the added value of most goods exported from Ukraine is often lower than the “intermediate consumption” of raw materials, components and fuels imported from abroad – also from Russia itself. Vivid examples of this include chocolate products with cocoa as the main imported ingredient, or mechanical engineering which has very close ties to Russian component suppliers. Steel or chemicals (especially the latter) are largely produced with raw materials, including ore, gas, oil and coal, imported from Russia or elsewhere. If Ukraine lost USD 2-2.5bn of its GDP by the end of this year under the worst-case scenario as estimated by the Federation of Employers of Ukraine, imports would also fall by at least USD 1bn. This would leave an actual GDP decline at USD 1-1.5bn or less than 1% of Ukraine’s current GDP.

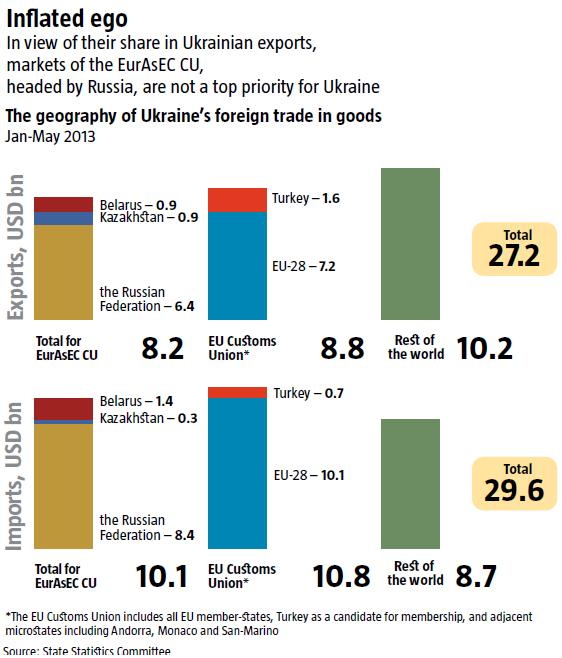

Another myth is that Russia or the CU is the biggest market for Ukrainian entrepreneurs, which they are not. The Russian and CU markets are far smaller, compared to the European one, which includes Turkey as a big importer of Ukrainian goods (see Inflated ego). Moreover, Russia’s share in Ukrainian exports was already plummeting before the trade warfare while that of the EU was increasing. Over Jan-May 2013, Russia’s share in Ukrainian exports shrank from 26.6% to 23.7% compared to the same period in January 2012, while that of the EU grew from 24.5% to 26.8%. Also, Ukraine’s exports are more diversified. According to the State Statistics Committee, EurAsEC (the Customs Union of Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan) and the EU accounted for under 1/3 of Ukrainian exports each in Jan-May 2013, while more than 1/3 is exported elsewhere. The share of such third markets largely includes Asia and Africa and is growing inexorably.

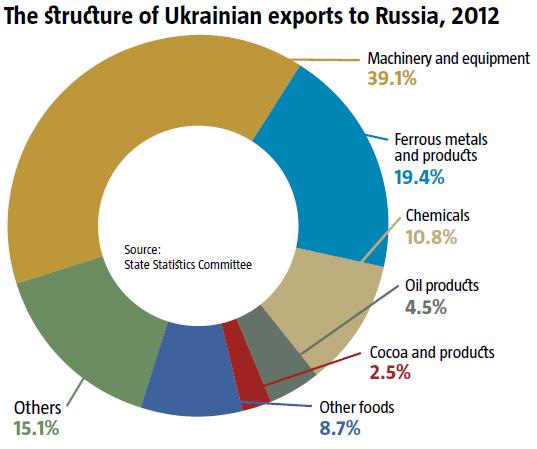

Despite significant risks for some Ukrainian producers, restrictions of exports to Russia, if Ukraine signs the Association Agreement, will not have a disastrous effect on Ukraine’s economy. In Jan-May 2013, Ukrainian steelworks exported just 13% of their output to Russia, chemical plants – 14.7%, and confectioneries – 22%. Ukrainian mechanical engineering sector is much more dependent on the Russian market. In Jan-May 2013, it exported 42.6% or USD 2.3bn of its total output worth USD 5.4bn to Russia. However, Russian producers are also heavily reliant on Ukrainian suppliers and have no substitutes for certain goods from Ukraine. Moreover, much of the industry’s products, even if made at facilities inherited from the USSR, are competitive in developed markets. The sector’s output accounts for 57.7% of Ukraine’s total exports to Estonia, 47.3% to Norway, 45% to Australia, 45.2% to Hungary, 35.4% to Latvia, 34% to Germany, 30.1% to the UK, 20% to Switzerland, 19% to Lithuania, 17.1% to the US and 17% to Finland, plus 21.7% to Iran, 8.2% to India and since the beginning of the year, 15.5% to China.

To partially solve its troubles with exports to Russia, Ukraine can re-orient towards other markets it already has and search for new ones. It should also focus on meeting domestic needs by cooperating with companies from developed countries. This, rather than the ongoing resuscitation of enterprises that are excessively focused on the Russian market, can help the development of mechanical engineering in Ukraine and offset losses on the Russian market. The Ukrainian mechanical engineering industry currently exports around USD 6-7bn worth of goods to Russia per year (USD 6.9bn in 2012 and far less this year, given the figures for the first six months of 2013). In 2012, Ukraine imported USD 22.4bn worth of mechanical engineering products. If it met at least half of its demand with domestically produced goods, with the localization of 40-50% of production, the output of the local mechanical engineering would grow by at least another USD 4-5bn. Plus, it would have a chance to develop cooperation with hi-tech economies, including European ones, whose governments do not to speculate on trade and economic relations for political purposes.

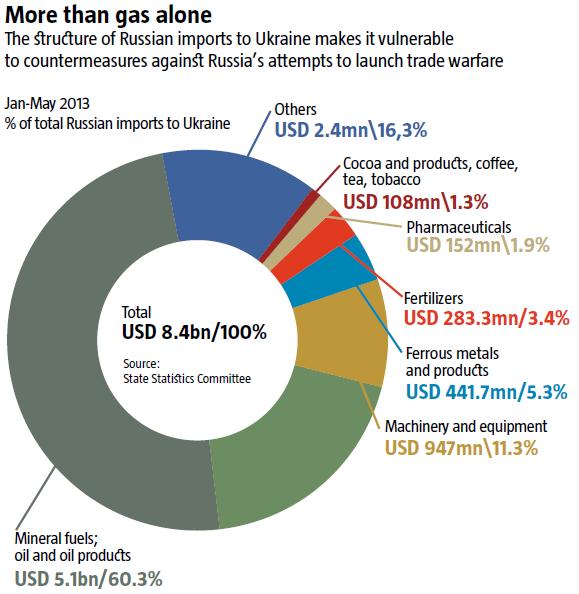

POTENTIAL FOR A RESPONSE

The initiators of trade warfare against Ukraine are confident that it will not respond in equal measure. They are used to Ukraine’s willingness to make concessions and in every new attack, accept Russia’s rules of the game. However, Ukraine could change this – and it has sufficient grounds to do so, making Russia more cautious. The first attempts have already been made. Ukraine has banned the import and transit of grain from the Siberian, North Caucasus and Southern Federal Districts. The official reason is foot-and-mouth disease in these districts. The Energy Minister, Eduard Stavytskyi, declared Naftogaz’s plans to further reduce the procurement of Russian gas and double the amount it buys from Europe from 2.5bn cu. m. in 2013 to 5bn cu. m. in 2014. Ukraine’s potential for discouraging Russia from abusing trade warfare comes from the high bilateral trade deficit. Over the first five months of 2013, Russia exported almost 25% more goods to Ukraine than Ukraine exported to Russia. Over 60% of Russian export to Ukraine is mineral fuels. The remaining 40% includes many goods which Ukraine could easily replace with domestic production, including ferrous metal products, fertilizers, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, as well as food, especially cocoa, coffee, tea and tobacco (see More than gas alone). Mechanical engineering products and related equipment join this lot as well.

Meanwhile, Russian exports of mineral fuels to Ukraine are vulnerable as well, especially oil, oil products, and coal. This is something Ukraine could easily replace with fuels imported from other countries. Several Western oil companies, such as Shell, BP, Chevron, ExonMobil, SOCAR or Arab companies, could replace Russian companies on the Ukrainian market with imported oil and oil products in the short run, or build modern oil refineries here in the mid-term provided that they have sufficient investment protection and incentives. As a result, Russia would lose a big chunk of its oil market. If squeezed even more on the gas market, Russia’s expansionist policy would be undermined. Russian coal could be replaced with that produced domestically. When all is said and done, Ukraine has been gradually diversifying its gas imports of late. If it imports 5bn cu. m. from Europe in 2014, Russia will lose over USD 2bn in exports compared to 2012. Once the offshore LNG terminal with its 5bn cu. m. capacity is launched, Russia will lose another USD 2bn in gas exports to Ukraine.

READ ALSO: Unconventional Prospects

Seeking solutions to the conflict with Russia under the WTO spirit is hardly efficient, given the length of the procedure and Moscow’s ability to cause more politically-motivated problems for Ukrainian exports. A more effective solution, especially after the signing of the Association Agreement with the EU, is to involve Brussels in negotiations. On the other hand, if the Association Agreement and DCFTA are signed and enacted, there will be no point in Russia continuing its trade warfare.

No matter what, the Russian market will remain extremely unreliable and one of the riskiest ones for Ukrainian suppliers. Thus, regardless of the outcome of the current trade warfare, Ukrainian companies should shed their excessive dependence on the Russian market. In view of this, the government would be wise to restrict any enterprise’s exports to Russia to 30%. This would rescue business and Ukraine from extreme scenarios in the future.