What’s going on? The answer to this on Ukraine’s politics, as well as economy interests many — especially as information about the economic situation in the country has lately been quite controversial. On one hand, the GDP grew the fastest in Q2’2019 over the period since the 2014-2015 crisis, the average wage has been growing in double digits for several years now, portfolio investors believe in Ukraine and bring in billions of dollars while global rating agencies improve Ukraine’s credit rating. On the other hand, some voices speak of the looming global economic crisis. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s industrial output has been falling for months, the budget is chronically underfunded, inflation stays above the targets set by the National Bank, and the dollar started rising sharply in early October, even if from a low level. So where is Ukraine?

The foundation of stability

After the 2014-2015 crisis, one could often hear that Ukraine had reached macroeconomic stability. What does this mean? Stability in the currency market means that there are no sharp fluctuations in the exchange rate, such as the ones Ukraine saw in 2008 or 2014. Stability in public finance reflects moderate state budget deficit that is under control and the government’s capacity to borrow to fund it further. Stability in the financial sector means that there is no panic among bank depositors, the inflow of deposits is stable and there is some bank lending. These are macroeconomic signals and factors of stability. They create a foundation that helps the economy grow. The rest is up to economic agents, i.e. enterprises and companies. They should invest, decrease costs and increase revenues in such favorable conditions. In other words, they should increase productivity as the key fundamental and long-lasting factor of economic growth.

Have economic agents been performing their part all this time? Generally yes, but their success is uneven. The analysis of official statistics on the dynamics of the real GDP and employment leads to that conclusion. If the State Statistics Bureau compiles data before and after the loss of Ukraine’s territory correctly, its statistics help to trace the change in productivity by industries. This helps to figure out the fundamental resilience of Ukraine’s economy by contrast to the superficial factors of the current market situation.

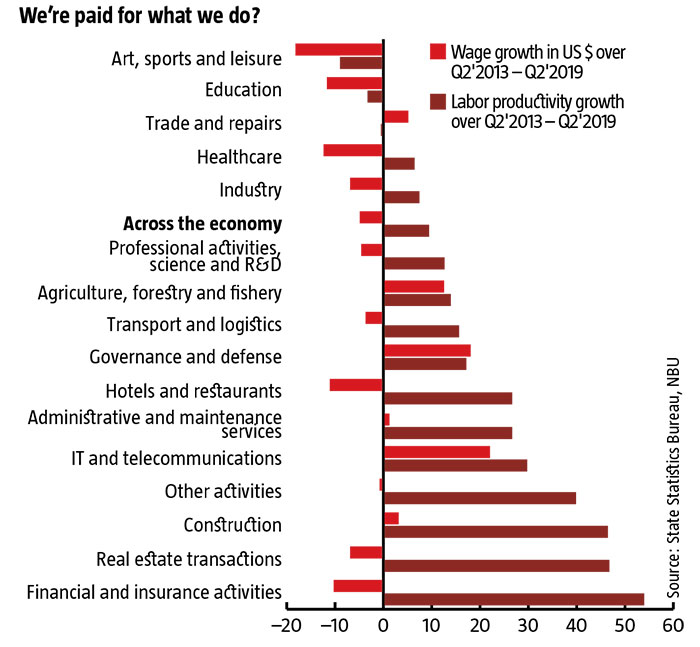

The State Statistics Bureau’s data for Q2`2019 shows that Ukraine’s real GDP has declined 7.2% since the same period in 2013. Added value has grown in nine sectors out of seventeen, IT and telecommunications leading the growth, and fallen in the rest. Employment has fallen the total of 15.1% in all sectors. This means that the actual labor productivity across the economy — the amount of the physical product produced per one person employed — has increased 9.2% (see We’re paid for what we do?). This fairly good result signals that the latest crisis has actually benefitted the economy. While being very shallow, this crisis forced enterprises and industries to learn from their mistakes and become stronger. As a result, the productivity of Ukraine’s economy today is better than it was six years ago. This is good.

Wages versus productivity

Average wages are another side of the coin. Economic theory says that the wage should reflect labor productivity. In Ukraine, wages have been growing for several years in hryvnia. Sometimes, this leaves one with an impression that this growth is unjustifiably fast. Statistics show that this impression in not ungrounded. According to the State Statistics Bureau, real wage was 21% in December 2018 than it had been six years earlier — there is no quarterly data for this, so the comparisons for wages move from Q2 to December. Overall, this is more than the growth in real labor productivity. This means that the economy is under some pressure of high wages. This is not very good as some companies will downscale if the pressure gets too high and they lose their profit. All this can result in an economic downturn.

RELATED ARTICLE: The new multivectoral economy

But this situation is not homogenous. Some exporters easily increase wages for their employees threefold thanks to the devaluation of the hryvnia, even if their nominal wages grew 213% over six years until December 2018. They fare relatively well. The companies operating on the domestic market see far lower revenues — high wages hit them more painfully. Therefore, it makes sense to analyze wages in dollar equivalent. The wage of Q2’2019 was 4.6% below that of six years ago (see We’re paid for what we do?). Given that labor productivity has grown 9.2% over that period, Ukraine’s economy retains some resilience in terms of export competitiveness. It can be summarized as follows: if the wage in the dollar equivalent increases another 14.5% in Ukraine, the economy will return to the Q2’2013 balance between wages and productivity.

Resilience is good. But it comes with two problems. One is that the dollar was worth UAH 26.56 in Q2’2019. If changed down towards UAH 24 per US dollar, the rate that persisted on the market just several weeks ago, the resilience will fade to 3.4%. The other problem is that Q2’2013 is not the best basis for comparison: it was than that the economy entered a visible pre-crisis period and reasonable economists were begging for a 15-25% devaluation of the hryvnia. Should this be used in a comparison? Probably not. Then the claims about resilience no longer seem so credible. This leads to the following conclusion: Ukraine’s economy was very close to the state of 2013 when the hryvnia went up to UAH 24 per US dollar several weeks ago. If that lasted a few months, it would launch ruinous crisis processes. For now, Ukraine has managed to avert it.

The game of industries

That is not all. The growth of real productivity by industries gives a lot of food for thought. The financial sector leads in terms of productivity dynamics with 54%. This is thanks to the banking reform, one of the most successful transformations after the EuroMaidan that drove unprecedented optimization in banks. As a side effect, nearly 100,000 employees were laid off — mostly in liquidated banks, but in others too as they closed down inefficient units. This led to higher competition for jobs and pushed wages in the sector 18% down in the dollar equivalent over six years. A huge positive implication, however, is the growth in productivity that may have made the financial sector one of the most efficient industries in Ukraine’s economy. The results are easy to see: banks make record-breaking profits and have built up huge resilience if anything happens to go wrong.

Construction comes third in terms of productivity growth. Residential construction for IDPs, massive repairs of roads and a spike in completed commercial real estate in the past months have all led to a 16% increase in the industry’s added value. It now takes 20% less staff to create this added value. This is the result of higher efficiency — especially as developers switch to civilized working rules (this is another successful reform, even if less comprehensive compared to the financial sector) — the inflow of dynamic public tenders for construction and the arrival of strong international players that have brought in the standards of high-quality work. As a result, construction has become one of the six industries where wages have grown in the dollar equivalent. This result is a happy surprise, especially as construction used to be a sector in Ukraine that employed people who could not find jobs anywhere else.

Agriculture, forestry and fishery have shown surprisingly poor results, adding a mere 0.9% in added value over six years until the end of Q2’2019. The widely praised driver of Ukraine’s economy is running out of steam. Its 14% productivity growth is purely thanks to lower employment as more agricompanies switch to new technology with minimum number of staff involved. The growth of wages in the agriculture sector has almost eaten up the growth in labor productivity. This means that agriculture is among the most vulnerable industries when faced with negative scenarios, such as further revaluation of the hryvnia, decline of global prices for agriproducts, poor harvest, sharp increase in salaries, etc. If that materializes, the driver may well turn into a break for Ukraine’s economy.

The industry, too, has some of the poorest results. It has added 7.2% in labor productivity over six years while losing 20% of added value. There are some exceptions to this: oil and wood processing sectors have increased their revenues by over 20%, while the production of details for cars has grown over 30% thanks to the newly-opened export-oriented factories. Overall, however, the industry holds Ukraine back: it accounted for over 21% in added value of Ukraine’s economy in 2018. The war in the Donbas pushed it further down and it has yet to recover from that blow. The outburst of protectionism in the world leads to a decrease in industrial output in most advanced economies. The only way to survive in such poor environment is by introducing new technology and modernizing as radically as possible. That is highly unlikely given that industrial companies in Ukraine are mostly in the hands of oligarchs. The nouveau richeare incapable of regularly improving efficiency; their mindset is different. Therefore, Ukraine’s industry is losing to the pace of wage growth dictated by the more successful sectors. For years now, news has been coming from different regions that employees quit factories and go to work abroad, while the owners fail to find a replacement for them due to low salaries.

The current trends

Based on the perspective, Ukraine’s economy either still has some resilience thanks to the beneficial balance between wages and labor productivity, or it has completely exhausted it. Different sectors have come to this stage in different shapes: some have huge resilience thanks to a leap in efficiency over the past six years; others have barely made any progress. How do current economic processes and trends layer over this foundation?

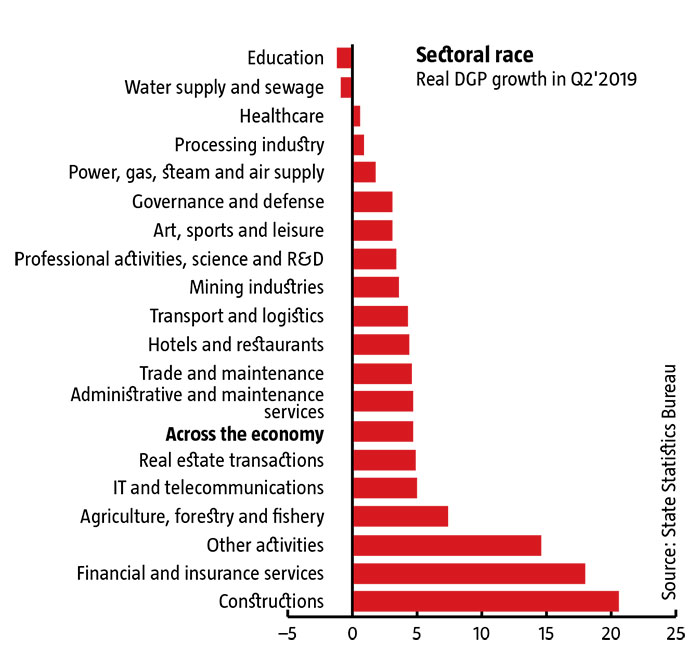

An analysis of the record-breaking GDP growth in Q2’2019 (see Sectoral race) points to a number of interesting conclusions. The construction sector was the champion of growth with 20%, primarily driven by non-residential development — mostly commercial real estate — and objects, such as roads and communications. Construction is likely to expand further as mechanisms of funding function well by now, the funding is included in the budget, and the new Government’s program pledges to repair 24,000km of roads in the next five years. Commercial property construction depends on the situation on the market, development of the economy and the growth of purchasing power in Ukraine. Therefore, the prospect of this segment is an open question.

The financial sector came second in terms of growth. The reasons are obvious: it has huge fundamental resilience described above; the purchasing power of the population grows steadily and drives the dynamics of lending; lavish revenues allow banks to quickly expand their operations. It is difficult to predict how long this growth will last. Neither individuals, nor businesses have received sufficient lending in the past years. This led to a financial vacuum, a sort of stifled demand. In theory, therefore, lending can develop for many more quarters, driving the entire financial sector forward — even in a crisis situation. Especially if interest rates go down in the economy. Still, the reality of the banking system in Ukraine says that the earliest signs of a crisis will push banks to automatically accumulate reserves. This could stifle their appetite for lending. Further growth of wages in banks seems dubious given that the economy is exhausting the room for it. It is therefore difficult to say now which factor will prevail, or how intense and lasting the development of the financial sector will be in the near future.

RELATED ARTICLE: Guarantor, referee and coach

Agriculture also saw considerable growth of added value in Q2. According to the sector professionals, however, this is mostly because the harvesting began two weeks before the usual. In Q3, they already felt less confident. The cheap dollar led to smaller revenues, especially for small and mid-sized enterprises. Some export-oriented primary processing companies were forced to stop as exporting their produce was no longer profitable under the then-exchange rate. The drought in Southern Ukraine means that the harvest will be at the level of 2018 or below that. Therefore, the pace of added value growth in agriculture is likely to go down by the end of the year.

In a sign of optimism, many sectors have increased their added value by 3-5%. This is sound development based on the increase of purchasing power in the population. If the dynamics of labor productivity in the economy stays as it is now, it will create conditions for an increase in wages and synchronized economic growth will continue. The only problem is that the normal pace of productivity increase is usually far below the growth of wages in Ukraine. In this context, the economy will reach the point of saturation sooner or later, leaving no room for wage growth and wiping out the foundation of the demand that feeds economic development across many sectors. It is difficult to predict when this will happen, but the moment will probably come soon enough.

Unsurprisingly, the industry lags behind. Global trends are likely to further aggravate this. A properly constructed government policy might change the situation somewhat, but it should then focus on the real entrepreneurs willing to plunge into the world of new technology and production, not on oligarchs. Any other approach is doomed to fail in the era of 3D printing and the Internet of things. As long as Ukraine’s government has no such policy, and it shows no signs of having one anytime soon. As soon as the economy faces any crisis, this burden of inefficiency will hit painfully. It can even overtake the development of other sectors and push Ukraine into an abyss of a new recession.

The essential elements

In a nutshell, Ukraine’s economy can be described in three groups of factors with varying levels of depth. The first group is comprised of fundamental factors that drive efficiency growth in some sectors and across the system. This is a perpetual motion machine of economic progress that pushes the economy forward regardless of whether it is in crisis or thriving. The analysis above proves that some of the reforms conducted after the Revolution of Dignity was the accelerator that sped up the machine. Even if the new government fails to intensify reforms, this group of factors will work for some time to boost the economy by inertia. If reforms speed up, the dynamics of labor productivity in some sectors can be faster, creating the conditions for an economic leap.

The second group is comprised of the factors of demand. They are based on the growth of wages that has approached the cap defined by labor productivity. The situation varies by sectors, but the room for increase is limited, if any. It’s for this reason that discussions on stimulating lending are taking place now. In theory, this can sustain demand longer than wage growth. This can also boost investment activities that are now slowing down – gross fixed capital formation grew 7.9% in Q2 compared to the far more impressive 14.3% in 2018. This will help to win some time to prepare a new stage of reforms. But this will not be an alternative to potential effect of such reforms. The government should realize that it has little time as the economic system might lose the inertia it now has. In a situation where everyone is preparing for a recession, any reform will hardly have its maximum effect.

The third group is the factors of the market. They have been very favorable in the past few months, leaving an impression that Ukraine’s economy is doing great. But this is misleading for a number of reasons. Firstly, the inflow of capital to Ukraine, primarily via government bonds, do not affect the fundamental resilience of the economy and have limited influence on domestic demand, – even if the latest government borrowings via bonds partly offset the missing IMF loans and other external borrowings, and partly ended up as dead weight on the Treasury’s accounts that are currently superfluous with liquidity. This money will not serve to build new factories, but it has had some impact on the foreign exchange market.

Secondly, Ukraine’s government bonds are far less attractive today than they were several months ago. The hryvnia has revaluated to a maximum, especially given the devaluation of most other currencies in the meantime. According to the NBU, the real effective exchange rate (REER) of the hryvnia was higher in August than it was in December 2013 at 0.98 versus 0.94. This means that the hryvnia had some room for revaluation under domestic criteria, even if fairly virtual, while having clearly exhausted it in international markets. Given the decline in the profitability of government bonds by 3-4 percentage points, foreign buyers of one-year government bonds had to pay 14.3% more in foreign currency for one hryvnia of the future money flow in the late September than in early April, shortly after the first round of the presidential election. In fact, hryvnia revaluation and the decline of interest rates almost ate up the yearly profitability of government bonds. After that, they lost attractiveness in the eyes of non-residents. This makes continued inflow of foreign capital into government bonds unlikely.

RELATED ARTICLE: Break out of the vicious circle

Finally, the political factor matters as well. The new government has made promising statements on domestic reforms and controversial actions in foreign policy. In addition to that, the leaks about talks with the IMF and the resignation of Oleksandr Danylyuk, a champion of the development of the whole country rather than of certain groups of interests, leaves one doubtful about the ambitious reforms pledged by the government, and about the fact that they would be conducted in the interests of the country and the people. The euphoria many in Ukraine felt after the change of government and shared by investors at some point may evaporate quite soon. It is then that Ukraine’s economy will face a test of reality, and not everyone will be happy about the results.

In any case, the war Petro Poroshenko waged against Russia allowed for far more certainty and predictability than the peace Volodymyr Zelenskiy aspires to. For investors, uncertainty is a red flag and an Exit sign above the door through which investment comes into Ukraine. As soon as the flag goes up, investors realize that the season of favorable conditions is over and it is time to prepare to leave. While 73% of Ukrainians are bewitched with Ze! President series, investors will be looking for some more interesting shows, and their money will follow them.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook