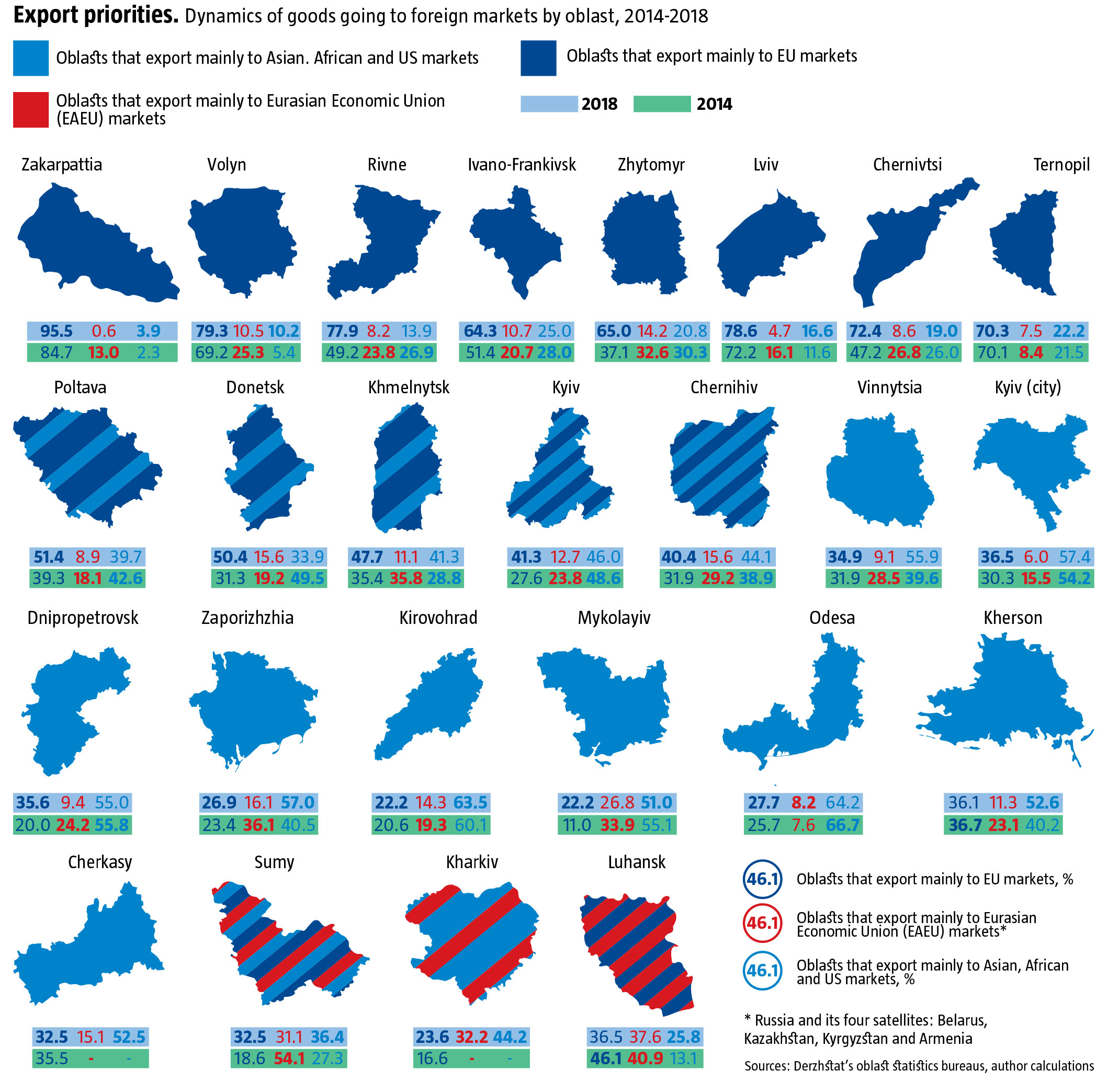

General indicators show that Ukraine’s economy has re-oriented itself towards trade with the EU: the share of member countries in overall volumes of Ukrainian exports is more than 42% today. However, some significant divergences can be seen at the regional level in recent years,

Adjusting to new realities

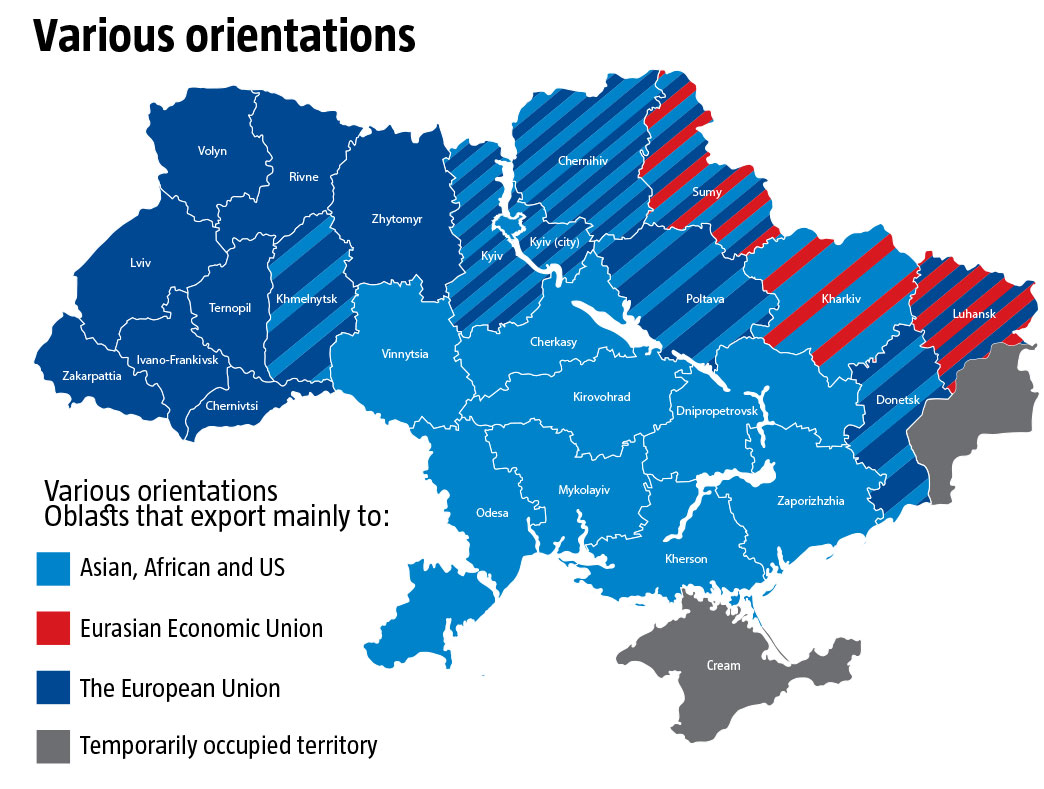

The old dilemma, EU or Russia – or the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) run by Russia—is no longer a reality. New divergences in foreign trade orientations have replaced the old ones, but this time at the regional level (see Various orientations). In time, these could become not just a factor affecting domestic policy but even the economic foundation for different geopolitical orientations in those regions. It’s no secret that even in the past, polls in the central and more particularly southern oblasts showed far more support for joining neither the EU nor NATO, nor Russo-centric entities. Still, the coming cyclical economic crisis in the world economy and specific regions of the globe will have a very real impact on the resilience of certain oblasts and the country as a whole.

Despite the serious geographic shift in domestic exports driven by Russia’s aggression and, as The Ukrainian Week has written, equally by a contraction in Russian imports from all countries because of the growing economic crisis in recent years in Russia itself, the absolute majority of Ukraine’s regions exported noticeably more in 2018 than they had in 2014, in euro terms. Significant declines outside of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts, which are suffering the impact of Russia’s occupation of major chunks of their territories, occurred in only three other oblasts: Kherson with -15.6%, Kharkiv with -21.0%, Kirovohrad with -28.4%. Two more oblasts, Dnipropetrovsk with -0.8% and Rivne with -2.3% in 2018 already posted growth early this year that outpaced 2014.

All the remaining regions have shown a positive growth dynamic to a greater or lesser extent, ranging from 0.6% in Kyiv and 1.0% in Poltava, all the way to 101% in Ivano-Frankivsk and 117% in Vinnytsia. Since 2014, exports to the EU have grown in 22 of Ukraine’s 25 regions that are not occupied. Even in Donetsk Oblast, which has lost half of its economic potential as a result of Russia’s occupation, exports to the EU from just the free territory were 4.6% more in 2018 than from the entire oblast in 2014: €2.07bn vs €1.98bn.

Uneven growth

But all this growth was fairly uneven. For instance, Kharkiv Oblast grew “a mere” 12.3%, from €227.1mn to €255.2mn, Odesa went up 13.6%, from €343.9mn to €390.7mn, Zaporizhzhia grew 17.0%, from €656.5mn to €768.3mn, and the city of Kyiv improved 21.3%, from €2.615bn to €3.171bn. Meanwhile, a slew of other oblasts saw their exports grow by factors: Kyiv improved 170%, from €385.2mn to €648.9mn, Dnipropetrovsk went up 180%, from €1.3bn to €2.3bn, Zhytomyr nearly doubled, from €185.6mn to €364.3mn, Sumy rose 220%, from €103.2mn to €220.8mn, Vinnytsia went up 240%, from €177.9mn to €422.6mn, Chernivtsi jumped 270%, from €45.9mn to €122.7mn, and so on. Only in three oblast did exports to the EU decline since 2014: Firstly, Kirovohrad fell 22.7%, from €127.1mn to €98.2mn and Kherson slipped 17.2%, from €99.5mn to €82.4mn. But what really stood behind a more than tenfold collapse in Luhansk Oblast, which went from €650.3mn to €62.7mn? Part of its territory taken over by an enemy and companies that contributed critically to pre-war exports from the oblast, or a decline in the latter on non-occupied territory? Today, it’s impossible to answer this properly given the lack of access to reliable statistics on external trade in specific counties and cities.

RELATED ARTICLE: Stop the vicious cycle

Some oblasts – Zakarpattia, Volyn, Rivne, Lviv, Ternopil, Ivano-Frankivsk, Chernivtsi, and Zhytomyr –have almost completely reoriented themselves towards the EU market, which now takes 65-90% of their export goods. This is almost the same level as Ukraine’s Central European EU neighbors. Moreover, these oblasts sell a healthy range of goods to European markets, compared to other areas of Ukraine. A handful of other oblasts – Khmelnytsk, Poltava and Donetsk – have so far only oriented about half of their exports to the EU, but both the volumes and the shares have been growing strongly in recent years, which means that they are slowly pulling up to the rest of the EU-oriented group.

Meanwhile the bulk of Ukraine, meaning most of the central and southern oblasts including economic dynamos like the city of Kyiv and the Lower Dnipro Valley, with Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhzhia, continue to post geographically diversified trade numbers, with a substantial share going to Asia, Africa and the USA – and generally in that order. The Russo-centric markets of the Eurasian Economic Union have long since become secondary for them, while the share going to Europe remains at the 25-35% level (see Export priorities).

What’s more, in most of the oblasts in this group, the share of trade with Asia, Africa and the USA has been growing in the last few years, as has its euro value. The reason is not only because these oblasts have been slowly curtailing trade with Russia or the EAEU. For some of them, the share of sales of goods to the EU has been going down, such as in Cherkasy and Kherson, or has been growing much more slowly, such as Vinnytsia and Zaporizhzhia. But there is a subgroup within the Asia, Africa and the USA group whose share of exports to the EU has been growing sharply: Kyiv, Chernihiv, Dnipropetrovsk and Mykolayiv. Still, it’s too soon to say how far most of them will move in this direction.

Turning backs on Russia

The group of oblasts that lie at the Russian border – Luhansk, Kharkiv and Sumy – remain very dependent on the markets of Russia and its EAEU satellites, for 31-38% of their trade. For most other oblasts, this line of trade has shrunk to 5-15% at this point. Today, only a small number of oblasts that showed modest but growing trade with the EAEU in 2014 continue to show growth: Mykolayiv has gone from €468.9mn to €479.2mn, Odesa from €102.4mn to €115.6mn, Ivano-Frankivsk from €75.8mn to €78.6mn, and Ternopil from €22.7mn to €28.6mn. However, only in Odesa Oblast has this been accompanied by a marginal increase in the share of the EAEU of all exports for the oblast. In the other three oblasts, even though volumes are inching up, this market is far slower than others, especially if we consider that sales to the EU are skyrocketing: from €188.5mn to €474.5mn in Ivano-Frankivsk, from €152mn to €397.2mn in Mykolayiv, and from €189.2mn to €269.4mn in Ternopil.

In all the remaining regions of Ukraine, there has been a more-or-less steady shrinkage, not only of the share but also the absolute volumes of exports to countries in the Russo-centric EAEU. In most of them, the decline in absolute volumes since 2014 ranges between 40% and 60%, while their share of overall exports is down 50-80%. In some cases, the decline has been over 90%. For instance, deliveries from Zakarpattia to the EAEU fell from €135.0mn in 2014 to €8.7mn in 2018, or down to barely 6% of what it was and the shares of these countries’ markets of total volumes shipped from the oblast have fallen from 13.0% to 0.6%.

Indeed, even the three oblasts on the Russian border can’t rightly be spoken about as “oriented on Russia” today, as the share of trade going to Russia is steadily declining and is almost at the same level as deliveries to EU markets or countries in Asia, Africa and the USA (see Export priorities). In Sumy Oblast, exports to the EU are already greater than those to the EAEU, while in Luhansk they are only slightly behind already.

In short, developments on the Russian market will now have a noticeable impact on the overall Ukrainian economy and its trade relations, as well as on individual regions, especially in view of the likely shakedown Russia is likely to experience as its role as a supplier of oil and gas on the world market declines.

EU = healthy diversification

Trade in goods from western oblasts to the EU is becoming a lot more diversified in terms of the range of goods although it is focused on the markets of a single world region. For instance, Volyn Oblast reoriented on the European market mainly with machinery, which constituted 45.8% of its trade and was worth €274.7mn in 2018. This export item has kept growing dynamically over the last few years, both in absolute volume and in its share of total exports from the oblast: in 2014, it was 43.2% and worth €222.6mn. This includes mainly parts for European companies as part of the manufacturing cooperation that has been developing, with electronics going from €139.8mn in 2014 to €190.4mn in 2018. Today, this is the leading item in Volyn Oblast’s exports. Wood products, furniture and paper products constitute 28.2% and are worth €172.3mn. In 2018, furniture exports were worth €44.6mn, while paper and cardboard products were worth €10.9mn. Foodstuffs constitute another 17.9% of Volyn’s exports, led by oilseed at €40.6mn and grain at €18.7mn. Processed foods are already at €14.1mn and meats at €12.8mn, with fruits and vegetables not far behind at €9.2mn. Finally, Volyn also exports a substantial €13.7mn worth of clothing.

The situation is similar in Lviv Oblast. The region’s main export is machinery, up to €429.6mn from only €279.0mn in 2014. Here, too, electronics have constituted the bulk of this growth, going from €247.9mn in 2014 to €384.5mn in 2018. However, at 24.7%, the share of furniture, processed wood and paper products is much higher than in Volyn, with furniture taking the lion’s share in its expansion, up at €198.2mn in 2018, compared to €84.9mn in 2014, together with paper and cardboard products at €39.5mn. Similarly, a larger share in absolute volumes and in relation to overall exports from Lviv Oblast is taken by clothing, footwear and other finished leather and textile products, 11.0%, having gone up to €177.9mn from €123.1mn in 2014. Foodstuffs account for 27.8% of all exports from Lviv Oblast, but their share of overall exports is higher than in neighboring Volyn, thanks to processed foods, which account for 14.9% and have gone up from €153.7mn in 2014 to €239.6mn in 2018. This is considerably more than shipments of grain and oilseed contribute, at €173.3mn or 10.8%. Among other items in the foodstuffs category, Lviv exports €15.2mn of fruits and vegetables, up from €4.1mn in 2014, and €8.3mn of meat, up from €6.3mn in 2014.

Given that the European market is relatively stable and even during a recession demand is unlikely to drop sharply, the coming crisis will likely lead to fewer tremors in the regions of Ukraine that are exporting 65-90% of their goods to the EU. If the range of goods in these exports continues to diversify, they should survive the next recession relatively painlessly.

The danger of export monoculture

But this diversification of goods and expanding share of products with a higher added value is lacking in the extreme in most of Ukraine’s central and southern oblasts. Even among those that are seeing export deliveries abroad grow more quickly in recent years, it’s still mostly based on the outdated tradition of mostly raw materials or products from branches of industry that have few prospects, such as the old steel industry.

For example, in Vinnytsia Oblast, 79.7% of exports are agricultural products, with 42.7% of it from the oil and fats industry and 19.2% grain. Only 3.8% is machinery, although electronic parts dominate on the European market. In Cherkasy, too, more than 83.0% of exports are also farm products, with 43% oils and fats, and 26.6% grains and oilseeds. The share of machinery is only 3.0%. Still, the share of wood products, furniture and clothing is growing in this oblast. Odesa Oblast also exports more than 72.0% farm products, mostly grain and oilseed accounting for 41.1%, while oil and fat products account for the remaining 20.9%. Processed foods constitute less than 3.0% of the oblast’s exports, while meats are an insignificant 0.1%. Although machinery represents over 16.0% of its export income, the shipbuilding industry covers 10.9%. The oblast basically does not export any of its finished products from the light industry. In Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, 23.4% of export earnings in 2018 came from ore, while another 45.0% came from semi-finished steel products. All told, products from the mining and metallurgy sector accounts for 78.5% of the oblast’s exports, while machinery is only 3.9%.

In some oblasts, the lack of options for expanding export has already led to stagnation and even step declines in trade. Kirovohrad, for instance, belongs to those oblasts with the greatest losses in exports in recent years. In 2018, 80.2% of its exports were agricultural products and ores. Moreover, in contrast to western oblasts oriented on the EU, the lion’s share, 42.3%, of this oblast’s farm exports are oil and meal by-product and 24.6% is grain. The share and volume of processed foods with a higher added value is minimal. Exports of other processed foods, light industry and furniture are all marginal as well. Only 14.0% of Kirovohrad’s exports are machine-building products, key among them not components that are integrated into global technology production chains, in contrast, once again, to western oblasts, but outdated leftovers of soviet manufacture that are ever less able to compete on world markets.

A comparison of the oblast’s exports in 2014 and 2018 shows that the main losses have come as a result of a steep decline in the volumes of oil and meal delivered to foreign markets, which accounted for 70.0% of its exports in 2014. No alternate markets for these products have been found so far. A similar situation faces in Kherson Oblast, another of the regions that has lost the most over the last four years. There, as well, 64.5% of exports were farm products and only 12.9% was machinery.

RELATED ARTICLE: The great balancing act

The more narrowly-focused profile of exports in oblasts oriented on Asia, Africa and the USA makes them also more vulnerable to fluctuations on global commodity markets and to potential crises on these markets. The likelihood of high volatility is ever present as rising prices for different commodities can spur strong growth, but when prices collapse, they can also lead to serious problems. Considerable geographic diversification in their export of goods is unlikely to be much of a bulwark as any collapse in prices is likely to be worldwide.

However, excessive export monoculture is a perpetual curse in all the central oblasts. For instance, Kyiv Oblast the share of farm products in total exports is also 64.4%. Unlike other central oblasts, however, the share of meat in its total exports is 25.0%, and the share of processed food is 9.2%, while 9.9% of the oblast’s exports are processed wood, paper products and furniture, 9.1% is chemical products, and 6.9% is machinery, with electronics taking the lead. Moreover, here the profile of exports is being reorganized as the share of exports to the EU grows (see map). Indeed, it looks like this oblast will soon join the group of EU-oriented regions.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook