The recent deterioration of Ukraine’s real economy has paradoxically coincided with relative stability in the currency market, finance, real estate development and trade.

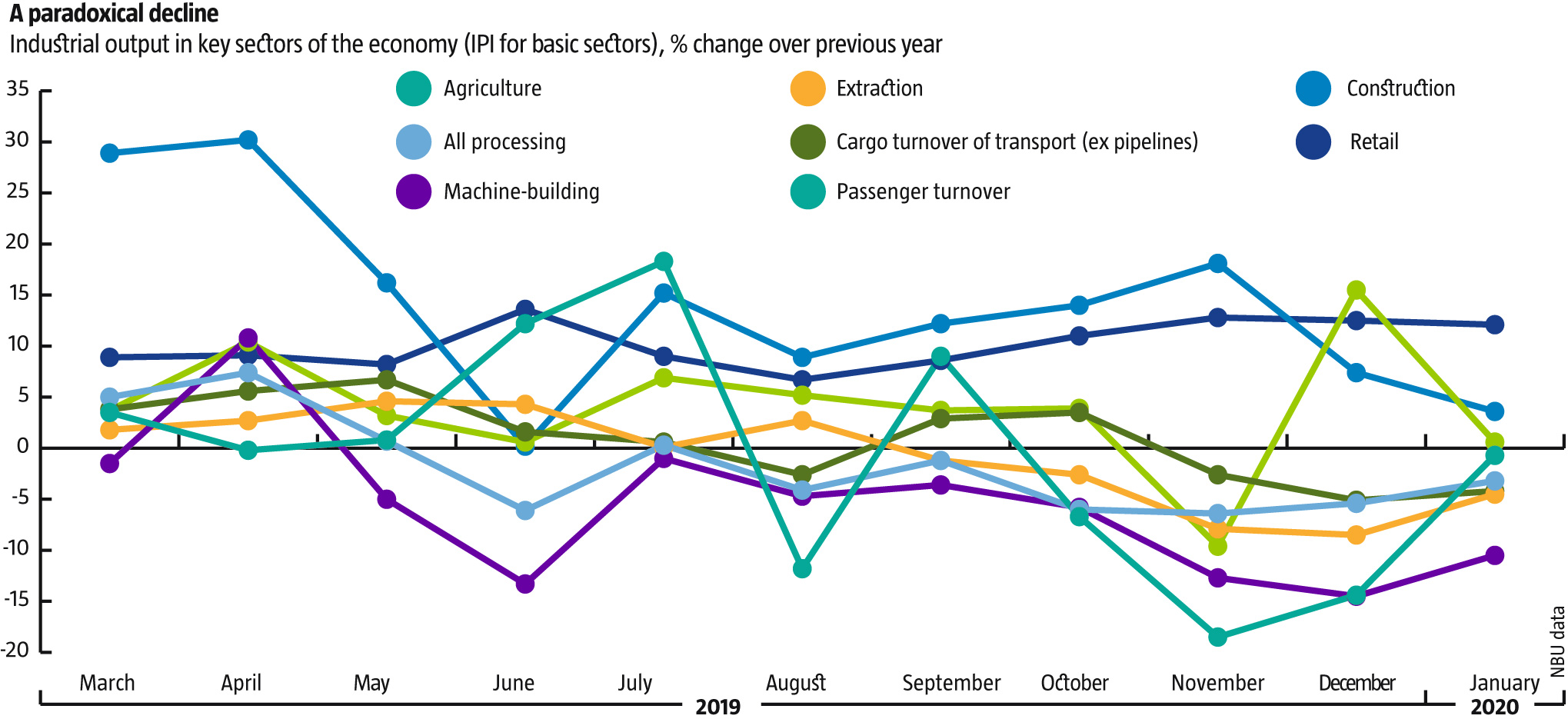

The slippage that picked up pace in Ukraine’s economy in the fall has continued into 2020. According to the latest data from the NBU, Ukraine’s central bank, the Industrial Production Index for the basic sectors fell 3.4% and output has been in decline in most sectors, including agriculture and transport (see A paradoxical decline). This is especially visible in metallurgy and machine-building, despite a slight recovery on global markets. Agriculture has lost pace compared to January 2019. In winter, farm sector output estimates are mostly based on livestock data, so they don’t depend on external factors like crops or weather. A decline of food output against growing consumer demand signals that Ukrainian producers are losing ground both domestically and internationally.

Meanwhile, the decline has slowly and predictably been spreading from industry and agriculture to other sectors of the economy, including the transport sector. A drop in November and stagnation in December were followed by a 2.3% increase in exports of goods from Ukraine in January 2020 and a slight dip in imports of 1.7%. Still, both numbers are misleading. Exports grew thanks to record-breaking sales of maize and sunflower oil, but these now offer no further growth potential. With domestic storage facilities full in anticipation of a gas war with Russia, imports went down because Ukraine bought the minimum volume of fuels and it was also buying less coal and oil.

Meanwhile, imports of food and industrial goods have expanded rapidly, as have the retail and construction sectors, especially residential housing.

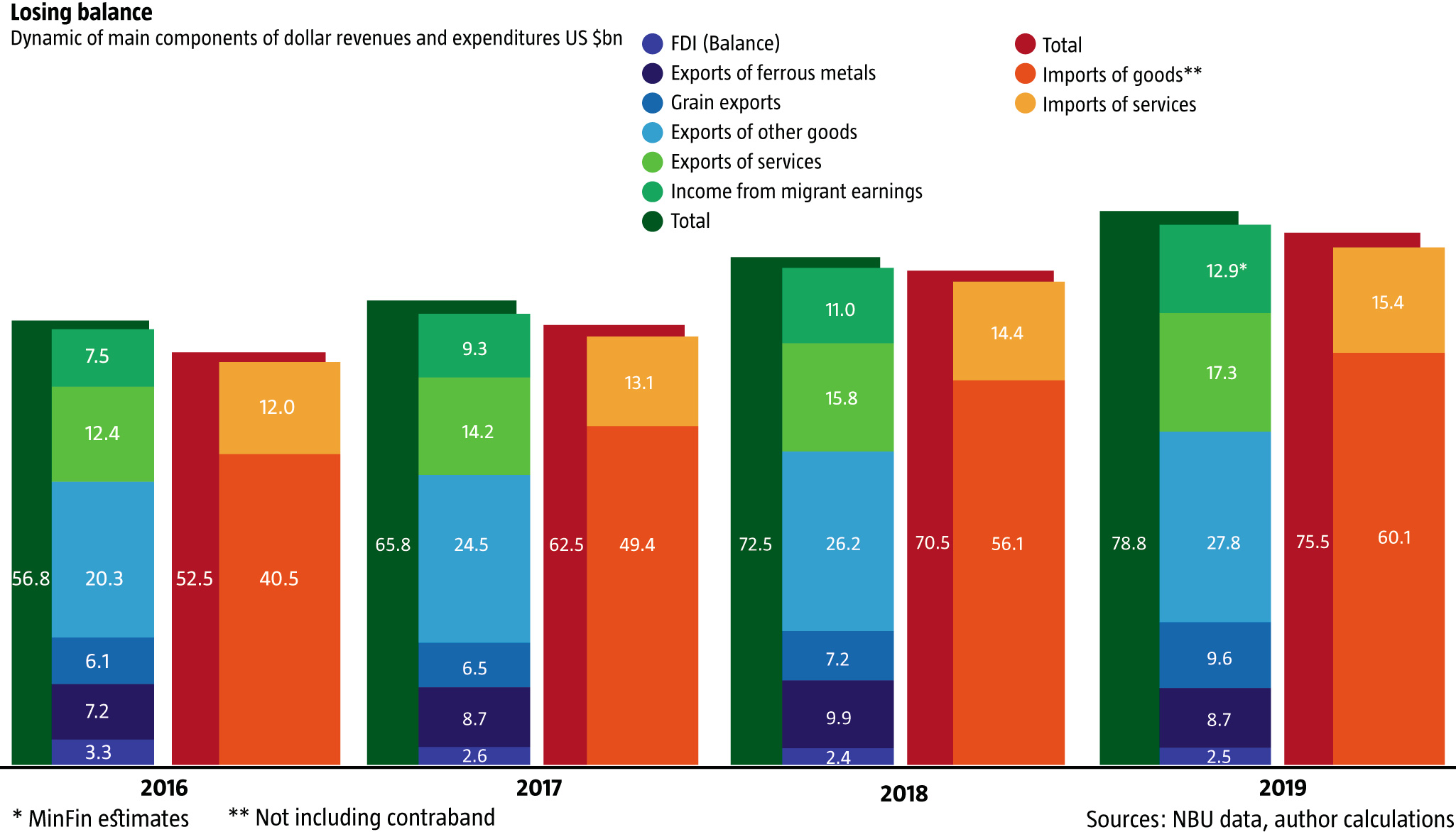

This seemingly paradoxical miscorrelation between the real state of the economy and consumption is because Ukrainians are increasingly living off the money earned abroad. According to the Ministry of Finance, migrant workers transferred US $12.9bn back home in 2019, up from US $7.5bn in 2016. The comparison of dynamics across different sources of foreign currency inflow to Ukraine shows that transfers from migrant workers have grown much faster in recent years than exports of goods and services, let alone FDI (see Losing balance).

The data on money transfers from Ukrainians working abroad comes from estimates. However, contrasted to the big gap between official imports and exports of goods, the situation on the foreign exchange market and the consumption boom points to the fact that government estimates of transfers by migrant workers are underrated rather than exaggerated.

A jog of imbalances

While such a massive influx of foreign currency without economic policy to match might seem to be an advantage for Ukraine, it actually hurts the economy. Labor migration from Ukraine makes the economy itself less competitive by boosting the cost of labor without protecting the domestic market from the inflow of imported goods.

RELATED ARTICLE: The coming crisis

Investing into expanding production makes less sense under these circumstances. Instead, it becomes more profitable to invest into trading in imported goods and services that are bought with the cash transferred home by migrant workers. Meanwhile, the tax burden on those working inside the country has to grow even more to pay for public and pension expenditures that are growing more costly as a result of a shrinking domestic workforce. Given these conditions, it is only effective to produce something that cannot be imported at a lower cost. And this almost exclusively means retail trade and services.

In December 2018, The Ukrainian Week pointed to the danger of Ukraine turning into a feeder community for the EU. This has led to systemic challenges for Ukraine’s economy, budget, social services, and demographics. Since then, these concerns have been confirmed and Ukraine has been moving even faster towards a confrontation with the problems caused by this transformation. Even at home, the suburbs and bedroom communities of big cities face a number of challenges, but mechanisms generally exist to balance out the problems at that level. However, they don’t work on the international level.

On one hand, Ukraine cannot keep its approach to taxation unchanged as it increasingly turns into a “feeder community” for wealthier European countries because this is based on a post-soviet social model. The ongoing shift will require a major rebalancing of mechanisms for taxation and filling public coffers to fund social benefits, education and healthcare. One way to do this is by extending mandatory contributions to the money being shipped home by migrant workers.

Of course, this will be problematic. But if Ukraine does not do something, it will see public services deteriorate ever more rapidly and the government will have fewer resources to fund them. Meanwhile fiscal and quasi-fiscal pressure will mount on those who remain to work in Ukraine. The current model of centralized funding for education, healthcare and social benefits built into the country’s Constitution did not foresee a scenario where a large proportion of able-bodied citizens would be making money outside the domestic economy.

On the other hand, such an approach would entrench Ukraine in its feeder role, even as it softens the impact of such a transformation.

One effective solution could be a radical change in economic policy. Ukraine needs to provide the conditions for most goods consumed domestically, including those purchased with the remittances of migrant workers, to be produced domestically. This would also generate additional jobs at home, encouraging migrants to return. However, this is impossible to do when the domestic market has no protection from the inflow of imported consumer goods, especially from Asian countries.

Trading in markets

For a large economy like Ukraine’s to develop successfully, it can’t rely on trade, services and the financial sector alone. It would always be insufficient under those conditions and have no a base for long-term sustainable development.

Obviously, different business groups have different interests in any given country and around the world. This has been very evident in Ukraine recently: what undermines domestic manufacturers and producers can meanwhile benefit those engaged in the retail, financial and services sectors. For example, last year’s revaluation of the hryvnia caused losses in the production and manufacturing in most areas, while retail trade kept growing and the performance of the financial sector improved.

Economic policy needs to be oriented primarily towards the interests of production and manufacturing, especially if the country hopes to have a strong global position. Production is the foundation without which sustainable long-term development is impossible for all the other segments of a country’s economy.

RELATED ARTICLE: Stay away

By contrast, Ukraine has seen in the past few decades how the domestic economy can become dependent on the interests of producers from other countries. Instead of nurturing and protecting domestic production in highly profitable and dynamic sectors that can deliver rapid economic growth, Ukraine has been allowing outsiders to profit domestically all this time.

As a result, Ukrainians spent over UAH 1.5 trillion on imported goods in 2019, most of which Ukraine could have produced itself. Data from Derzhstat, the statistics bureau, shows a growing share of imports in the consumption of many groups of goods, year after year. While, in 2005, imported goods accounted for 29.5% of all goods sold in Ukraine and 42.4% for non-food items, by 2019 this share was up to 58% and 64.7% for non-food items.

Another visible trend in recent years has been a decline in critical imports of fuels and commodities, and in spending on imports of machinery and equipment that Ukraine needs to upgrade its industries but cannot manufacture domestically yet. Meanwhile, basic consumer goods made abroad are steadily strengthening their position on Ukraine’s domestic market.

Cherchez the importer

Counter to stereotypes that Ukraine’s economy is being hurt by the shift in trade towards the West, trade to the east has actually undermined the country far more. For example, the total trade deficit with China over 2009-2019 was more than US $41.5bn, and it was similar, albeit lower, with other Asia-Pacific countries like South Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Thailand. Meanwhile, all these countries actively restricted access to their domestic markets for finished goods, in order to support and protect their manufacturers – and many still do so. Meanwhile, Ukraine is virtually unprotected from the inflow of finished goods from the profitable, dynamic industrial sectors of these countries. At best, Ukraine supplies them with mostly raw materials, in far smaller volumes.

A change in trade regimens with them could give Ukraine a real chance to establish and nurture new production facilities at home, substituting some of the current imports and entering the markets of its other big suppliers of goods. Increasing taxes on imported consumer goods could play a twofold role: boost the development of domestic production in areas where it is lacking, and fill state coffers, providing an opportunity to minimize taxes on domestic businesses.

Foreign suppliers should be given access to Ukraine’s domestic market provided that their markets are open to Ukraine’s finished goods without endangering any segments of the country’s own economy.As some goods are not made in Ukraine but could easily be, access to the market should be adjusted to encourage these importers to gradually localize production in Ukraine. Of course, it’s important to prevent the domination of foreign economic players on the domestic market and to regulate both access and presence based on Ukraine’s national interests.

Protecting your own interests

Ukraine’s potentially strong position lies in its current structure of exports, which remains mostly raw materials and focused on the countries that are major net importers of these same materials. Clearly, they are not interested in closing their markets to Ukrainian suppliers. At the same time, their finished goods do not represent a major market share in Ukrainian, either, which is now overflowing disproportionately with ready-made products from countries that tend to keep their markets closed to most Ukrainian goods.

A policy of protecting the domestic market needs to be coupled with profound changes in lending and financial policies. Public policy should encourage ordinary individuals to save more, generating financial resources that can then be lent to domestic producers, rather than boost consumer lending. It only stimulates crediting for imports. This seems to be the only approach that can deliver rapid economic progress in Ukraine.

A low level of accumulating funds and investing into production is one of the major obstacles to rapid economic growth in Ukraine. The most successful economies around the world show that gross accumulation of capital at a level of 30-40% of GDP and priority investment into profitable production sectors provide opportunities to quickly renew the structure of an economy and accelerate growth. Right now, Ukraine is looking at less than a third of these figures.

RELATED ARTICLE: Inflationary nosedive

In the 20th centuries and earlier, capitalist development has proved that poor underdeveloped countries never become advanced and wealthy without at least a period of economic nationalism. Improving domestic economic and political development and living standards is impossible without mechanisms to protect and stimulate the economy to offset the artificial advantages of countries with more advanced economies or even just individual sectors. Otherwise, an economy will always remain subordinate, its activities determined by the interests of other countries.

Ukraine needs to change its approach to trading with different partners and start pursuing its interests first and foremost. Changes in trade that have lately accelerated in the world should be used to benefit its domestic interests. Given its current export structure based on raw materials, growing dependence on transfers from migrant workers abroad, and high levels of imports of finished consumer goods that could easily be produced domestically, Ukraine has plenty room to open opportunities for itself that could seriously improve its economic situation.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook