On August 29, 2019, the single-party Sluha Narodumajority in the Verkhovna Rada established the leadership of the legislature and approved a new Government under Oleksiy Honcharuk. That day, The Ukrainian Week published an article stating that Ukraine’s economy was close to the crest of economic growth and could very rapidly shift into a painful decline. This came at the peak of euphoria over news that Ukraine’s GDP had picked up to 4.6% growth in QII 2019, exports were rapidly rising thanks to a record grain harvest, and the hryvnia was growing stronger by the day.

Unfortunately, this and QIII’s 4.1% growth were effectively the final phase of economic growth for 2016-2019, almost completely renewing or even surpassing pre-war indicators. Since then, the signals appear to be indicating the approach of economic decline. Throughout the fall, the negative consequences of the new administration’s economic and budget policies were only reducing the competitive advantages of domestic producers, tightening the spiral of import and credit dependence, and undermining long-term demand on the domestic market.

However, the direction taken by the “economic guru” as newly-elected President Volodymyr Zelenskiy called his PM, suggests that the economic challenges facing the country have not been properly assessed. Oleksiy Honcharuk announced that the economy would grow 40% during Zelenskiy’s five-year term, from 3.7% to 4.8% depending on what happened already in 2020. Nothing was mentioned, however, about the growing signs of a crisis and the need to set counter-cyclical policies in motion to support domestic producers in the face of global currency and trade wars that are picking up momentum. Meanwhile, the new Cabinet’s 2020 Budget was aimed primarily at reducing the deficit by squeezing domestic demand and paying off foreign debts was made the priority.

The snowball effect

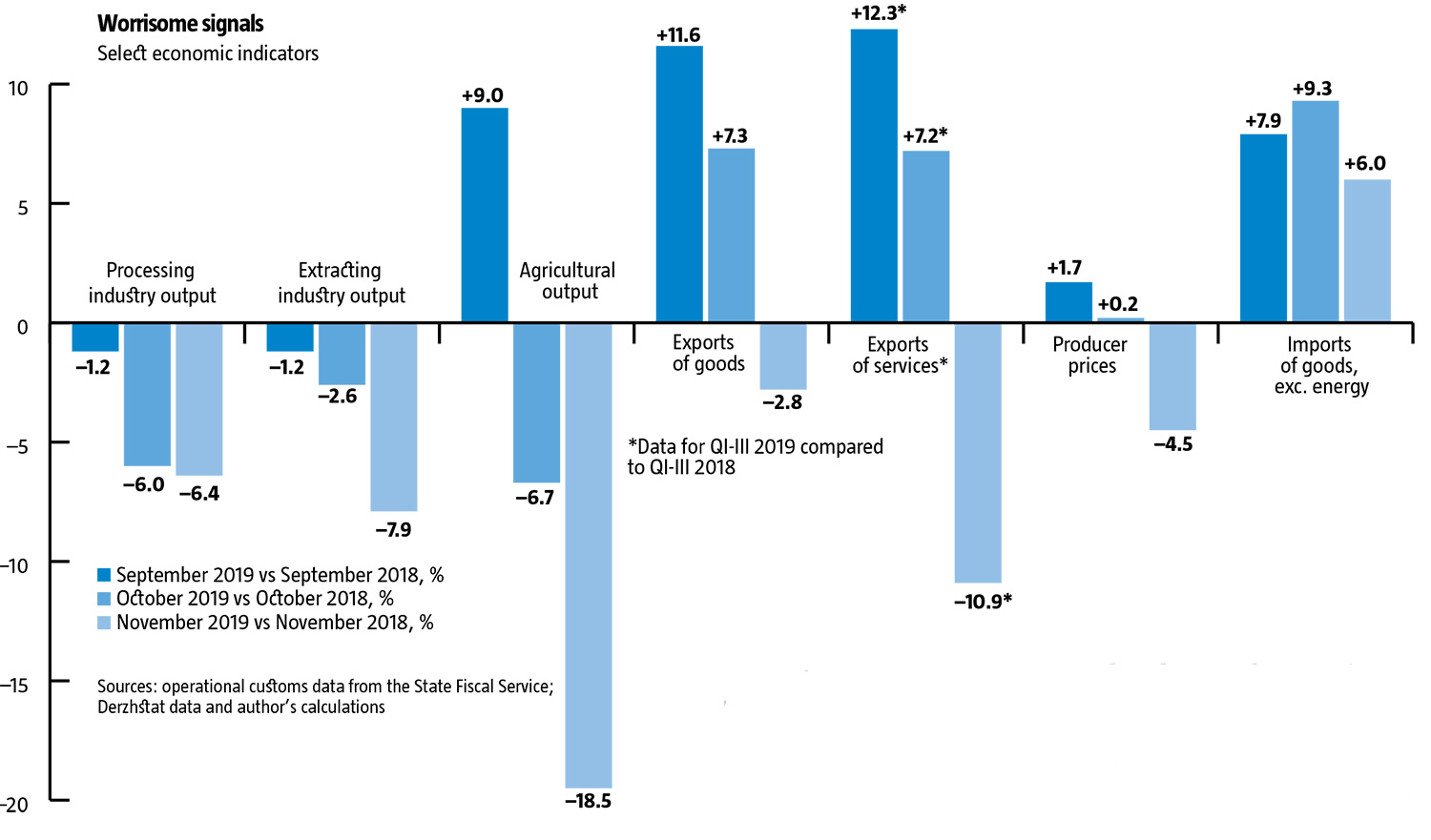

Meanwhile, the signs of a crisis continue to spread among more and more areas of the manufacturing sector. Industrial output has been falling steadily, down 1.1% in September compared to last year, down 5% in October compared to 2018, and had fallen by half again, 7.5%, in November.

RELATED ARTICLE: A reality check

The steepest decline has been in the steel industry, where it was down 14.3% in November compared to 2018, after slipping 11.9% in October and 5.4% in September. Closely tied to metallurgy, the coking industry was down 7.1% in November after slipping 3.4% in September. Ukrmetalurgprom, the industry business association, predicted that metal production would fall 36% this past December, compared to December 2018, with steel output expected to have dropped from 1.9 million t to 1.2mn t and cast iron to have fallen from 1.83mn t to 1.25mn t.

Despite the official positions of the Government and the central bank, the decline in Ukraine’s metallurgical industry cannot be seen as simply the reflection of world trends in the industry. For instance, in neighboring Russia, steel production declined only 2.9% in November in 2019, compared to 2018. In India, the industry suffer a similar decline, 2.8%, while South Korea slipped a mere 0.5%. Meanwhile, China increased production by 4.0%, while Vietnam’s output surged 24.0%. Ukraine lost more than 20% of its steel production in November, falling to 15thplace among top world producers, behind not just Iran and Turkey, but also Vietnam and Mexico.

Worse, the metallurgical sector, whose problems the Government tried to place on world trends, was not the only declining sector. Light industry has also been losing pace rapidly, declining 10.1% over 11M 2019. Wood-processing was down 5.9% for 11M but 8.6% for November alone, compared to 2018. More recently, a serious decline can be seen in machine-building, which lost 12.7% in November – the vehicle-making and car parts manufacturing sector was down 15.4%. The electronics and optics manufacturing sectors are doing even worse, down 25.7%. Just about the only predominantly export-oriented sector that continues to thrive is the furniture-making industry.

Over October-November, the decline spread to most other industrial sectors, including one oriented primarily on the domestic market – food processing. Where food processing posted growth in September, 1.6% compared to September 2018, in October it declined 4.3%, slipping further to -4.7% in November. What’s more, production was cut across the board in this sector, from meat processing or canning to dairy, confectionery, baked goods, and beverages. Despite a growing trend that had lasted some time, the autumn saw another sector oriented almost exclusively on domestic consumers, pharmaceuticals, contract by 1.0% in November.

Signs of a looming industrial crisis grew worse with a decline in producer prices: in October, they inched up 0.2% only to fall 4.5% in November. In October, they were down in the processing industry by 4.6% from 2018 and 6.0% down in November from 2018. And although falling prices for industrial products and a decline in output were mainly inherent to metallurgy and coking, they affected machine-building, wood processing and the chemicals industries. Stagnation was also evident in food processing. In a situation where production costs remain steady or even rise, lower selling prices as a result of the stronger hryvnia cut into producer profits to the point that some even went into the red.

With growing volumes of power and coal being imported from Russia at dumping prices, a process that picked up in the fall of 2019, domestic coal extraction immediately went into a dive. The decline in November compared to 2018 was 10.4% and nearly four times what it was in October, 2.3% and seven times what it was in September, 1.5%. For the domestic market, this fall in extraction volumes has been even stronger than that of metal ores, which fell 8.9%, which is due to the deteriorating global market. These two factors have combined to accelerate the decline in the entire extraction industry almost three times, from 2.6% in October to 7.9% in November. Meanwhile, extraction in the third largest component of this industry in Ukraine has remained about at the same levels as in 2018, slipping only 0.9% in November.

The farm sector posted solid growth in the first three quarters of 2019 and helped to pull the entire economy to a large extend, but it also started to decline in QIV. For one thing, food processing contracted by 6.7% in October, falling 18.5% in November compared to the same period in 2018. This gives reason to fear that QIV will end up with a very poor performance overall. Most likely, this decline will continue into 2020, too. At least two factors support this pessimistic outlook. First of all, the sector has been posting steady growth for two years in a row now, and typically after this kind of growth, at least with crops, there tends to be a temporary recession as yields go down. Secondly, investment in the agricultural sector has been falling for several years now. Indeed, for the first three quarters of 2019, it was less even than in the same period of 2017. It looks, thus, like the ag sector will post a serious fall-off in 2020.

After the pace of growth slowed down from 11.6% in September to 7.3% in October, exports of goods actually declined in November, falling 2.8%, from US $4.46mn in 2018 to US $4.32mn in 2019. Meanwhile, non-energy imports of goods continued to grow fairly rapidly, ranging from 6% to 9% during the three fall months. But in 2020, Ukraine is likely to see a decline in exports of agricultural raw materials added to these factors.

With exports of services, which have traditionally compensated for a shortage of trade in goods in Ukraine, the situation is even worse. By QIII this year, exports of services had fallen off by 10.9% compared to 2018 and prospects for 2020 don’t look much better. The cutbacks in transit gas from Russia has only added to the general negative trend that has been taking shape since mid-2019. At least the basic agreement that Gazprom will supply 65bn cu m in 2020, about 30% less than in 2019 has already been made public. The thing is that transit gas has constituted about a quarter of Ukraine’s exports of services in the past.

The growing hryvnia has made imports of consumer goods more attractive while reducing the competitiveness of Ukrainian-made goods. And so imports from global manufactories like China and other major Asian producers have been growing, effectively squeezing out made-in-Ukraine products – other than raw materials – on both the domestic and international markets. In the first half-year, imports averaged around US $653bn a month, but by August they were up to US $903bn and up to $965bn in October. This is being stimulated by the rapid construction of a government bond pyramid, which the Honcharuk Government has been turning into a panacea at a time when budget revenues are not strong as intakes from customs duties and taxes have generally gone down. This pyramid of debt is driving down the cost of imports in hryvnia terms, worsening the problem with collections for the budget and requiring ever more borrowings, which drives the hryvnia up further and reduces collections even more.

Exhausted compensators

The processing industry constitutes only 11% of Ukraine’s economy, with the farm sector at 10%, the extraction industries at 6%, and the power industry at 3%. However, put together that adds up to nearly one third of the country’s GDP. This means that a highly likely coordinated decline is liable to drag the rest of the economy down with them. For now, it’s holding on thanks to retail sales, construction and, to a lesser extent transportation, which are being spurred by both a sharp improvement in household incomes in the last few years and the remittances sent home by migrant Ukrainian workers – and, of course, the transport and sale of imported goods. But for one thing, the share of these sectors in GDP barely amounts to 21%. For another, should the manufacturing crisis become full-blown, affecting the export of its goods, this trio will also feel the pain.

The growing hryvnia also means that the remittances from abroad are actually shrinking in local terms, while the belt-tightening budget passed for this year is likely to put pressure on the buying power of those Ukrainian consumers who remain in the country. This is because wages in key sectors are indexed at a level that is slightly above inflation and two-three times lower than was seen over 2017-2019. As the domestic market gets squeezed, the crisis will begin to affect the other sectors of the economy that serve it.

More than this, domestic problems are likely to be added to the external challenges in 2020: the world economy is also heading for its next cyclical crisis and could well be as bad as the one in 2007-2009. The signs of this are growing daily. In the US, industrial output is slowing down, having slipped 1.1% in October on an annual basis. It’s also slowing down in the EU, losing 2.2% in October compared to 2018, and down from 1.7% in September. Major consumers of Ukrainian goods such as Italy and Germany have seen an even faster decline, Italy losing 2.4% in October and Germany losing 5.3%.

RELATED ARTICLE: A dangerous euphoria

Even in the most liberal societies with historical traditions of limited government interference in their lives, dissatisfaction with the limited role of the state in regulating socio-economic processes has been on the rise. As a night watchman, it no longer pleases anyone as it eliminates the options for effectively responding to the challenges of the day. More and more, it’s being recognized that that the nation-state is a major component of success and security in the modern world. This is what should protect the national interest on foreign markets. How much longer must Ukraine’s domestic economy continue spiraling into degradation and vulnerability before its leadership becomes aware that public policy regarding the economy needs to be overhauled?

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook