Ukrainian media have recently reported that minimum wage in Ukraine has surpassed that in Russia and Belarus. This is mostly the result of a steep hryvnia revaluation in the late 2019, followed by some backslide. However, the mere fact has drawn attention to another important theme — the dynamics of socio-economic development in post-soviet states that have followed different paths in the past decades.

The advocates of Eurasian integration and all kinds of reunions in Ukraine are proactively working on a myth about much higher living standards in Russia. At the same time, they focus public attention on socio-economic decline in specific periods in Ukraine, especially after the Revolution of Dignity, without comparing the process in Russia during the same time. In reality, the effectiveness of Putin’s socio-economic model is far lower even compared to what Ukraine has with all its flaws that hamper the fulfillment of its economic potential. By contrast, Moscow is earning huge revenues from minerals that are in demand on the global market.

It is extremely important for Ukrainians to recognize this fact, especially as the debate about the benefits of restoring economic cooperation with Russia intensifies after Volodymyr Zelenskiy came to power. This is presented as a tool for improving living standards or speeding up Ukraine’s economic development, and as a change of approach towards a more “pragmatic” one despite the war and clashes in the political sphere. With its increasingly stagnating economy and social model, Russia is not that instrument, nor can it be one — especially as the key socio-economic indicators in Ukraine are as good or better than in Russia despite the painful losses as a result of the war in the Donbas, and the ensuing destruction of production chains and the decline in living standards for Ukrainians.

A Russian nesting doll

Nominal GDP is used to compare the economies and living standards between countries. Russia’s nominal GDP was 3.9 times higher than Ukraine’s in 2013, but the gap has sinceshrunk to 3.1 times in 2019 (at $11.200 and $3.600 respectively) — the assessment for Ukraine includes a 10% depreciation to reflect the territory under Ukraine’s control (total nominal GDP is divided by all residents of the country; for Ukraine, 10% of its population lives in the occupied parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts). For the same reason, Ukraine’s GDP appears far lower in the data from the State Statistics Bureau compared to 2013, even though it should obviously be adjusted to the change of the real population of the Kyiv-controlled territory from 43.1 million (without Crimea) in 2013 to 38.3 million, according to the latest data from the Regional Civil Registration Offices. This is the number of citizens within the Kyiv-controlled territory by which GDP should be divided. Without the 11.1% of the population in the territory Kyiv does not control, Ukraine’s real GDP per capita was 4.3% higher in 2019 than in 2013. Russia’s GDP grew 4% at best over the same period. This performance of Ukraine’s economy mostly reflects a steep decline in 2014-2015 caused by active war in the Donbas and a shock from the destruction of production chains. Starting from 2016, Ukraine’s economy has been growing at least twice as fast as the Russian economy.

RELATED ARTICLE: The coming crisis

Going down from the general DGP figure, an abstract measure for many citizens, to the income of average people reveals minimal or no gap between Ukraine and Russia. According to the latest data available from October 2019, average wage in Russia was the equivalent of $729, just 65% above average wage in Ukraine. By comparison, it was $914 in October 2013, beating Ukraine’s $411 by 122% or 2.2 times. Minimum wage has grown in Russia from $165 as of January 1, 2014, to $196 as of January 1, 2020. Minimum wage in Ukraine has gone from $150 to $196.

Identical minimum wage and the 65% gap between average wage in Ukraine and Russia in the dollar equivalent with the threefold gap in GDP per capita between the two countries points to the fact that the redistribution of income from national economies to average citizens is far better in Ukraine than it is in Russia. The growth of income in Ukraine since 2013 at a far higher pace than in Russia (where average wage has actually declined since then) shows that average citizens benefit more from the Ukrainian economic model.

If these trends are to persist, the fact that average wage in Russia is higher seems temporary at first sight. Moreover, it is distorted by the high cost of living and greater regional inequality. For example, average wage in October 2019 was $729 across Russia and $1,400 in Moscow, and sometimes higher in the northern regions with the difficult climate focused on the mining of minerals —$ 1,578 in Chukotka, $1,409 in Yamalo-Nenetsk Autonomous Okrug, $1,367 in Magadan Oblast, $1,100-1,200 in Yakutia and Kamchatka, $1,050 in Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, and $966 in St. Petersburg.

All these exceptions boost Russia-average figures. In reality, average wage in most of Russia’s regions is around $450-550, which is close to Ukraine’s average of $440 in October 2019. These regions include both the oblasts adjacent to Ukraine, such as Briansk ($455), Kursk ($513), Voronezh ($523), Rostov($526)and Belgorod($548) oblasts or the Russia-occupied Crimea ($532), and the distant oblasts, such as Saratov ($438), Kirov ($467), Tambov ($450) or Oryol ($457).

Even compared to average wage in Ukrainian oblasts that are close to the Russian border, the numbers will not differ much: Donetsk Oblast has $491, Zaporizhzhia — $441, Kharkiv—$376, Luhansk—$374, and Sumy—$365. In turn, the gap between these regions and places where average wage is much higher, such as Kyiv ($651) or Kyiv Oblast ($465), is noticeably lower than the fourfold gap in Russia.

When the difference in the pricing of goods and services is taken into account, the gap in purchasing power of the wages is minimum between most Russian and Ukrainian regions. According to RosStat, the Russian statistics bureau, a kilogram of beef cost an equivalent of UAH 175 (based on the official NBU exchange rate) in Rostov Oblast, UAH 183 in Kursk Oblast, UAH 187 in Briansk Oblast, UAH 222 in Moscow, and more in the wealthier northern regions. A kilogram of pork cost UAH 122 in Voronezh Oblast, UAH 123 in Rostov Oblast, UAH 128 in Briansk Oblast and UAH 157 in Moscow. Chicken leg quarters were priced at the equivalent of UAH 60 in Rostov Oblast, UAH 62 in Briansk Oblast, UAH 63 in Kursk Oblast, and up to UAH 75 in Moscow. Apples ranged from UAH 24 in Rostov Oblast and UAH 28 in Briansk Oblast to UAH 39 in Moscow. A standard haircut for men was UAH 138 in Rostov Oblast, UAH 158 in Kursk Oblast and UAH 240 in Moscow. The same service for women was 20% more expensive. Prices in Russia are far higher than in Ukrainian regions.

Below is the comparison by individual oblasts. For example, two neighboring regions adjacent on the two sides of ORDiLO in Russia and Ukraine are Rostov Oblast with the average nominal wage at $526 and the Kyiv-controlled part of Donetsk Oblast with $491. Most consumer goods and services are more expensive in Rostov Oblast compared to Donetsk Oblast. Electricity is more expensive there too, even though Russia has lately been trying to take over the Ukrainian market by selling it at dumping prices via Belarus or directly. According to the official website of Rostov Oblast, the subsidized rate for electricity for households is 72% higher than the rate in Ukraine since January 1, 2020 at RUR 3.96or UAH 1.55 per kWh, and the full rate is 29.2% higher at RUR 5.53 or UAH 2.17 per kWh. While gas is severalfold cheaper in Russia than in Ukraine, the tariff for heat in Rostov is the equivalent of UAH 1,060 per GCal, which is just over 30% below the rate in Mariupol, the biggest city in the adjacent Donetsk Oblast in Ukraine. Public transport is more expensive in Russia too. For example, a bus trip in Rostov is the equivalent of UAH 10.2 compared to UAH 8 in Mariupol. Average wage in Mariupol at UAH 17,000 with nearly 500,000 inhabitants hardly differs from average wage in Rostov-on-Don at the equivalent of UAH 18,000 with its million people. Public transport is more expensive elsewhere in Russia too. In Belgorod, across the border from Kharkiv, it costs almost UAH 10.

Between stagnation and crisis

Unlike Ukraine where periods of sharp declines in the economy alternate with vibrant renewal, Russia has been in a lasting stagnation. These socio-economic trends in Russia grow more pronounced with time, contrasting sharply with the rapid growth during Vladimir Putin’s first two terms in office. Russia’s GDP in 2008 was 67% above the rate of 2000. Ever since Putin returned to presidency in 2012, the Russian economy has grown slightly over 6%. The neighboring China has the same pace of growth annually. Poland, Hungary and Romania have been growing 4-5% every year, and wealthy EU countries, such as Germany and France, grow faster than Russia too.

In his recent address to the Federal Assembly, Putin declared an intention to accomplish higher GDP growth for Russia compared to the worldwide rates in 2021. For this, he plans to fund various programs from the budget more proactively. The money will come from the funds accumulated from exports of fuels. Yet, this looks more like a face-saving effort in the context of a pessimistic economic outlook.

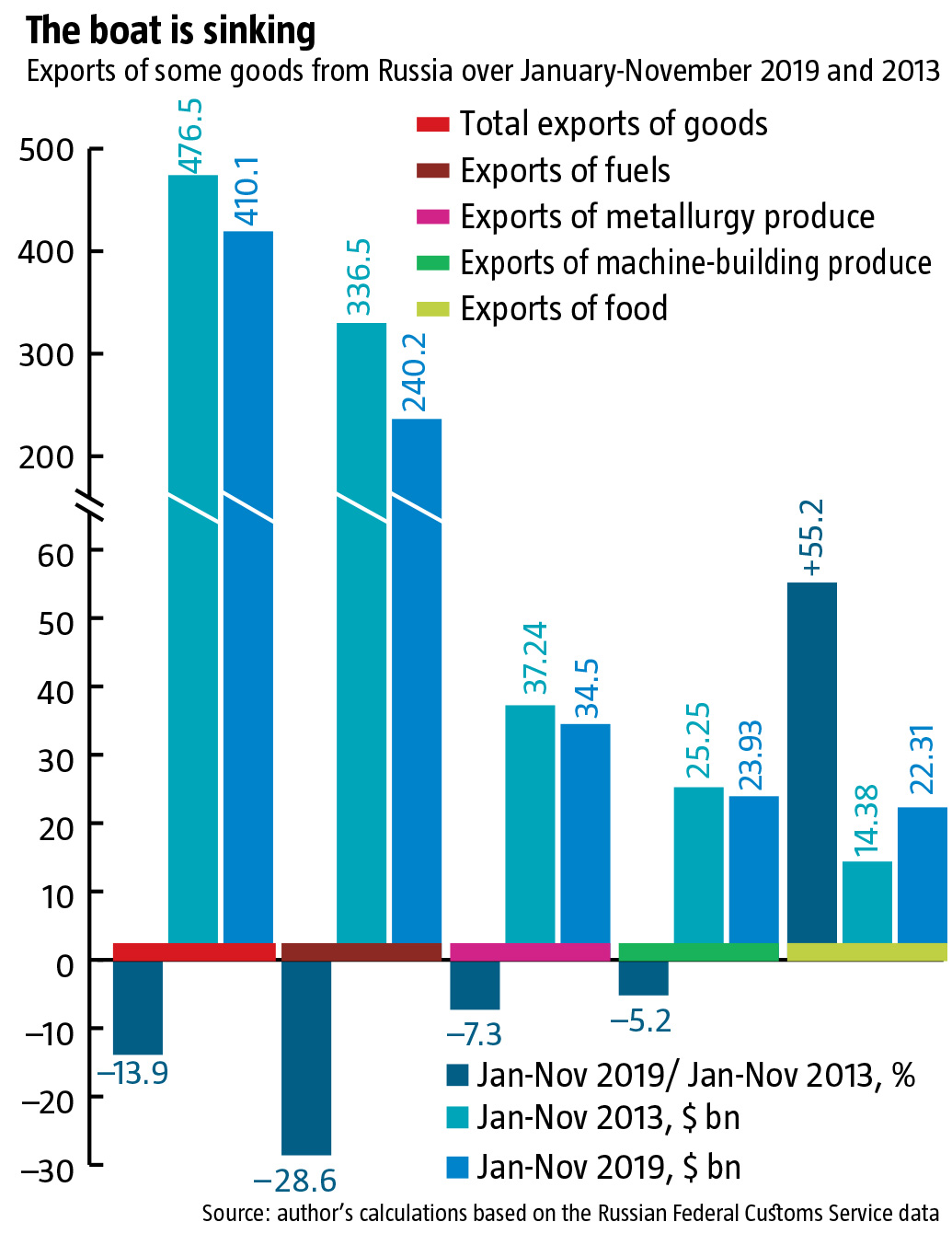

Given the figures on Russia’s exports in 2019 and 2013 (see Oil dollars don’t help), it is not just exporters of fuels that are struggling. Other sectors of the economy, from metallurgy to machine-building, are in the same position. The agricultural sector is only one that has managed to improve over the past years, however Ukraine is its biggest competitor. Meanwhile, Russian imports have plummeted even lower than its exports over this time. As the economy stagnates, the capacity of the Russian market shrinks. This is a key reason for the downfall of Ukrainian exports to Russia, not the “breakdown of traditional economic ties” as propaganda puts it. Imports from other post-soviet countries, including Russia’s closest partners, Belarus and Kazakhstan, are on the same path.

Even the most optimistic forecasts expect Russia’s economy to grow under 1% annually despite the stimulating measures Putin has announced. Russia’s Ministry of Economy projects GDP growth at 1.7% in 2020, and the Audit Chamber offers nearly 1.5%. Yet, even 2% — provided that Russia’s economy does not tumble into a crisis scenario — is far below the average growth rates in the world or the dynamics of most neighbor-states.

Therefore, stating that a return to the Russian orbit of influence or a rapprochement with Russia on a greater scale than in the pre-Maidan period would allow Ukraine to avoid or solve socio-economic problems faced in the past years has no ground. Economically, Russia is a bad and hopeless objective, while restoring ties with it will not ensure the promised positive effect for Ukraine. Moreover, better dynamics for some of Ukraine’s indicators compared to those of Russia, as observed lately, is the result of weaker interdependence between the two economies.

RELATED ARTICLE: Colonial misbalance

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook