For years, statements that the Russian market was the biggest for Ukrainian goods were one of the cornerstones of Kremlin propaganda to keep Kyiv within Moscow’s orbit. Unfortunately, the EU market is far more important for Ukrainian suppliers than the Russian Federation today. The notion that Ukraine couldn’t survive without Russia even under wartime conditions because it continues to be in first place for exports of Ukrainian goods, so Ukrainians should think long and hard and move back to the past, to traditional markets, continues to float around to this day. In 2019, even this myth is doomed to failure.

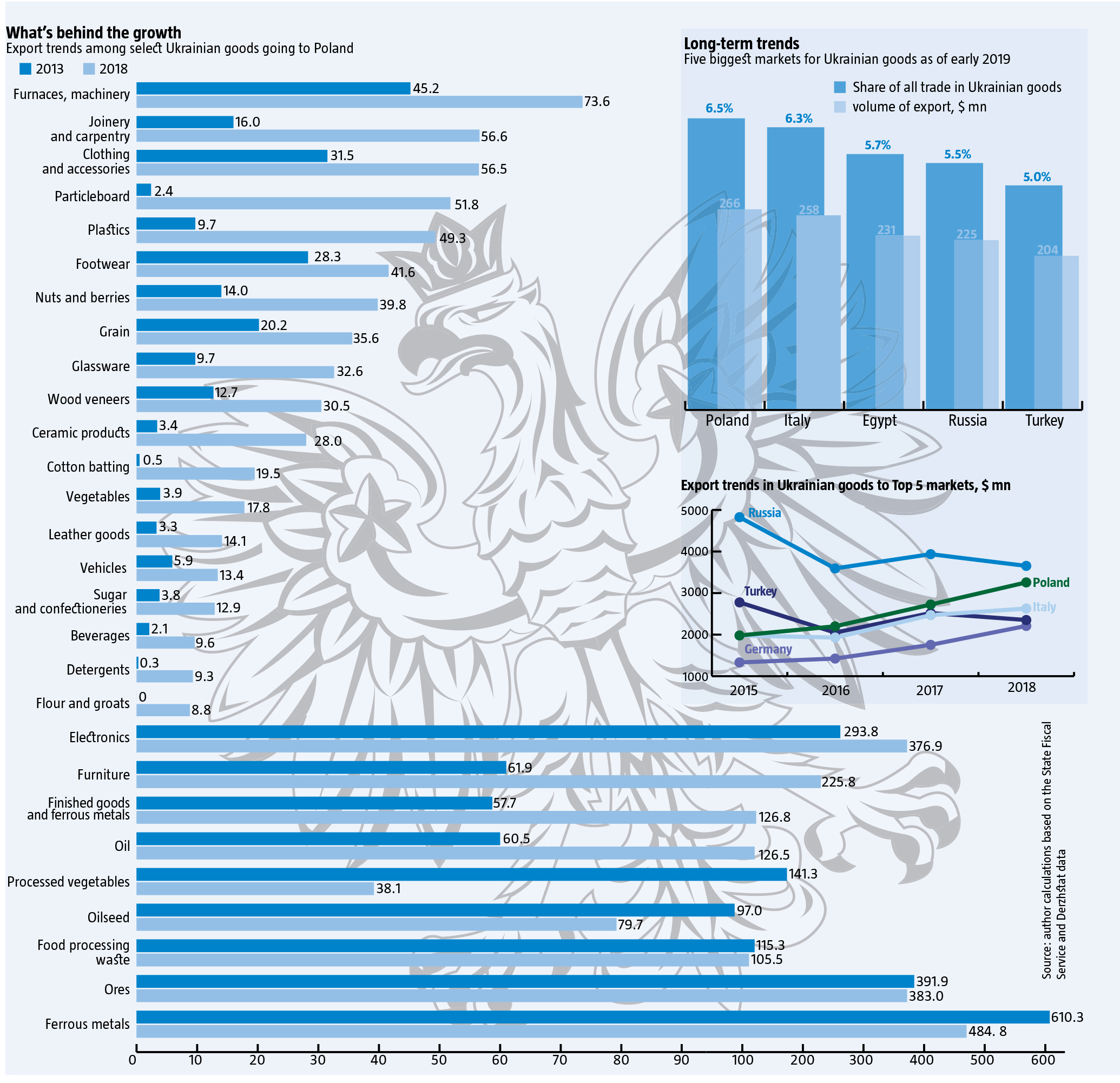

Trade figures from the beginning of 2019 showing that bilateral trends predicted that Poland would move into first place for volumes of sales of Ukrainian goods, as The Ukrainian Week wrote, and this has come to pass. The increase in Ukrainian exports on the Polish market were driven by its strong growth, one of the fastest in Europe with an average of 4% growth per year over 2014-2018. And although not much of Ukraine’s export was directed there, 6.5% of total exports, this proved enough for Ukraine’s western neighbor to reach the #1 spot as the country continues to diversify its trade geographically. Next after Poland is Italy, which is only a few tenths of a percent behind, with Egypt third at 5.7% export. Russia is only in fourth place after these three, after having been first for years: only 5.5% of Ukraine’s trade goes there, which is only a tad more than fifth-place Turkey.

Both growing exports of Ukrainian goods to Poland, which rose from US $254mn in January 2018 to US $266mn in January 2019, and declining exports to Russia, which fell from US $264mn in January 2018 to US $225mn in January 2019, pushed Poland into the top position. Nor was this just a one-month trend, but a sustained one. What’s more, where exports to other Top 10 countries like Egypt, India and Italy are monospecialized and very dependent on seasonal fluctuations and prices on basic products, which leads to figures that can shift wildly from month to month, Poland and Russia get quite diversified exports from Ukraine, leading to relatively stable figures month after month.

Between 2013 and 2018, Poland’s share grew from 4.0% to 6.9% while Russia’s collapsed from 23.8% to 7.7%. Today, this steady trend has finally led to a clear shift from Ukraine’s eastern aggressive neighbor to its western one, which is gradually taking on the role of a window to Europe in the face of constant speculation on the part of those who favor a return to Moscow’s imperialist orbit. Poland’s slightly smaller share in January 2019 compared to 2018 is deceptive, as January is typically the month when countries that buy mostly grain and oils temporarily overtake countries with whom Ukraine enjoys more diversified trade. When the main wave of trade in these goods to distant markets in Asia and Africa peters out, the share of European partners typically grows.

What’s behind the growth

Looking at the shifts in Ukrainian exports to Poland over the last five years by category of goods, it’s clear that, in addition to iron ore and ferrous products, quite a few finished goods with higher added value are also being shipped. For instance, electrical wiring, household appliances, furniture, a very wide range of wood products from carpentry and joinery details to chipboard, veneer and plywood, clothing and textiles, power, soy and rapeseed oils, preserved vegetables, and fruit juices. Compared to this, mining and extraction products, and agricultural products constitute a clear minority.

RELATED ARTICLE: Persuasive economy vs uncertain policy

What’s more, dynamic growth is taking place precisely in those positions that have a higher added value, while raw materials and semi-finished products are shipping in smaller quantities since 2013. For instance, food groups fell substantially, with oilseed going from US $97.0mn in 2013 to US $79.7mn, while processed oils more than doubled, from US $60.5mn to US $126.5mn. From negligible, meat products went to US $3.8mn, cocoa products went to US $6.3mn, while flours and groats went to US $8.8mn. Exports of sugar and confectioneries grew from US $3.8mn to US $12.9mn, grain products went from US $1.6mn to US $7.3mn, processed vegetables from US $3.9mn to US $17.8mn, processed fruits and nuts from US $14.0mn to US $39.8mn, and various beverages went from US $2.1mn to US $9.6mn.

The same can be seen in other branches. For instance, between 2013 and 2018, deliveries of Ukrainian ores shrank from US $ 391.9mn to US $383.0mn and unprocessed ferrous metals fell from US $610.3mn to US $484.8mn, while finished ferrous products more than doubled, from US $57.7mn to US $125.8mn (see What’s behind the growth)

Overall, the Top 20 Ukrainian goods that are sold to Poland, each of whom brings Ukrainian manufacturers at least UAH 1 billion every year, altogether account for more than half of all domestic exports to Ukraine’s neighbor. No single product is more than 10-15% of total deliveries, and the absolute majority isn’t even 1%, but this makes Ukraine’s exports to Poland very diversified and barely vulnerable to changes in prices or demand for any given product.

In addition to the UAH 9-10bn worth of electrical wiring that Ukraine exports to it annually, Poland is also Ukraine’s main foreign market for furniture. Annual sales of domestic furniture makers are close to UAH 6 billion. Moreover, another few billion hryvnia of high value-added processed wood products are sold in Poland every year. Last year, UAH 800mn worth of household appliances, from washing machines and air conditioners, to heaters, irons, lighting equipment and so on, were sold in Poland. Even batteries are a serious export these days, as is processed food, especially fruit juices, of which Ukraine sold UAH 400mn, plus UAH 300mn worth of confectioneries with sugar but without cocoa, and UAH 150mn worth of yeast. Ukraine also shipped nearly UAH 90mn worth of dairy products. Other exports that bring hundreds of millions of UAH in sales include plumbing equipment, ceramic tiles, clothing, footwear, baby carriages and strollers and spare parts, leather and paper products, detergents, and cosmetics. Last, but not least, Poland is a major market for electricity generated in Ukraine, taking nearly 25% of overall exports, UAH 2.2bn, in 2018.

Indeed, the Polish market it the main export market for an entire series of Ukrainian products: 94% of all baby carriages and strollers go there for nearly UAH 180mn, 83% of all rubber and plastic footwear, nearly 80% of all aluminum products for UAH 630mn, 63% of cucumbers, nearly 58% of all ceramic plumbing equipment for UAH 350mn, 58% of all particleboard, 56% of air conditioners, 55% of seating furniture, 48% of canned tomatoes, 38% of cloth footwear, more than 33% of detergents, 30% of washing machines, and 32.5% of carpentry and joinery details.

For Ukrainian SMEs, delivering to this solid neighboring market is the easiest, especially if compared to the distant markets of Asia and Africa, let alone the Americas. Moreover, Polish companies have long been interested in various forms of joint ventures with Ukrainian partners. Domestic firms are also actively making money on the export of services to Poland, although this indicator, unlike goods, puts Poland at a considerably lower level compared to other EU countries, like Germany and the UK. Overall annual turnover is currently US $343mn, while the profile is strikingly different from exports to other countries: nearly 50%, US $160mn, is income from the processing of Polish materials by Ukrainian companies on a tolling basis.

However, even the cumulative income from the export of goods and services to the Polish market is lower than the export of Ukraine’s labor force. Here, Poland has also overtaken Russia for first place in providing jobs to Ukrainian migrant workers and for repatriated earnings. In 2017, Ukrainians working in Poland sent home more than US $3.1bn, while the first quarter of 2018 was up 45% over the same period of 2017. Clearly, repatriated earnings far outstripped what Ukrainian exporters made on the Polish market. 2019 is likely to continue the trend.

What’s next

The steep rise in the weight of the Polish market for Ukrainian producers, which led to that market surpassing the once-largest Russian one early this year, could pose a number of risks in the longer term. Already Polish businesses are complaining. During last year’s Europe-Ukraine forum, the vice president of the Ukrainian-Polish Chamber of Commerce reported that Polish agri-business is already calling for special restrictions on Ukrainian suppliers. If Ukraine’s SMEs, in particular, continue to focus on trade with Poland, they could develop a dangerous dependency, similar to Ukraine’s one-time reliance on Russia, the consequences of which Ukraine is still trying to overcome.

No one should dismiss the possibility that Warsaw could try to use Kyiv’s trade dependence to put pressure on Ukraine, both economically and politically down the line. Given the unhappy experience of historical and ideological confrontations over the past few years, trade wars and the possibility of using bilateral trade as a way of “putting Kyiv in its place” is not nearly as hypothetical as one might hope. Should this come to pass, any overdependence on the Polish market could make Ukraine’s business unacceptably vulnerable.

RELATED ARTICLE: The poorest country in Europe

Fortunately, there is some indication that Poland will not remain in the #1 position as a market for Ukrainian goods for long. For one thing, Italy is already breathing down its neck. But the biggest threat to Poland’s primacy is the growth in the overall value of trade with Germany, which is slowly closing the gap, once the Association Agreement comes into effect. Since 2013, exports to Poland have jumped 60% more than exports to Germany. However, by 2018 the gap was already down to 47%: last year, trade with Poland grew 19.6%, while trade with Germany grew 25.9%. In January 2019, Ukrainian exports to Germany grew nearly twice the rate of exports to Poland, compared to January 2018.

The German market is potentially a far larger one for Ukrainian goods and German business is a much more powerful trading partner for Ukrainian manufacturers than Polish business. Moreover, exports to Germany are quite diversified as to both goods and services. Moreover, lately sales are up of products that were either not provided in Germany at all or were provided in very insignificant amounts until recently. And so Poland could turn out to be just an experimental site for a large-scale entry of Ukrainian producers into stronger European markets.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook