The closer it gets to the presidential elections in Ukraine, the more we talk about the poverty in the country. Many people are saying that Ukraine has become one of the most impoverished countries in the whole of Europe. This topic is frequently discussed in two dimensions. On one hand, the poverty faced by many Ukrainians is often seen in contrast with the “excess luxury and wealth of the corrupt officials and oligarchs”, who are apparently the true reason behind the everyday misery of ordinary Ukrainians. On the other hand, there is a populist comparison to the “good old days before the coup” favoured by the pro-Russian, revanchist forces, who insist that “Euro-reformers” and “Maidan’s authorities” are somehow the reason why so many Ukrainians have become destitute. In both cases we are dealing with extremely popular stereotypes aiming to explain the roots of poverty in Ukraine. These stereotypes have nevertheless very little in common with reality. Just the opposite, they distract public from the real reasons why many Ukrainians are struggling to make the ends meet and why country is facing such hardship. Therefore those above-mentioned explanations are not addressing the problem of poverty in the country, while its scale may endanger the very existence of the Ukrainian state.

Dangerous stereotypes

There is a myth that claims that the reason behind the poverty among many Ukrainians is a great income inequality. This myth is based on assumption that the narrow circle of the affluent and rich ones, who accumulated large amounts of wealth, are root of the problem. At the same time, it is clear that in case this wealth was re-distributed among several millions impoverished Ukrainians, those funds would not be sufficient to make those latter ones wealthier. Yes, indeed everyone would potentially receive extra few hundred – at least no more than a thousand – of hryvnias each month, but this would definitely fail to solve the country’s poverty issue or make its citizens happier. One of the main reasons for this is that the national economy’s ‘cake’ is way too small to feed everyone and, sadly, each year, instead of growing, it melts way. Henceforth regardless of how this ‘cake’ is divided and distributed – it won’t solve the poverty problem.

On top of that, it is similarly a myth that the Revolution of Dignity and the so-called “removal of the professional bureaucrats” from the government and the subsequent disruption of the economic and trade relations with Russia and its satellites led to the deepening of the poverty crisis in Ukraine. Fervent supporters of this claim present three arguments. First of all, they argue that right after the revolution of 2014 the poverty pushed many Ukrainians to seek working opportunities in the neighbouring European countries. Secondly, the costs of the utility bills, especially gas and heating have increased much more in comparison to the regular household income; and thirdly, equivalent of salaries and retirement payments in dollars is considerably lower compared to 2013. All those three factors are populist manipulations, which, have, nevertheless, found fertile ground in Ukrainian society. After all, Ukrainians are the poorest people in Europe, especially when owing to the recent lifting of some job market restriction they’ve been comparing themselves to the other countries in Europe.

It is true that recently Ukrainians have been frequently traveling to various European countries seeking for work – but not necessarily because Ukraine became poorer or unemployment have become unbearable. One of the key reasons is that access to the European job market became easier, while the flow of economic migrants to Russia has decreased. It is also true that costs of utilities, especially gas bills, have grown disproportionally higher compared to the average household income. At the same time, however, costs of other services have been increasing slower than the consumers’ income; additionally, during the previous government the cost of utilities has been kept artificially low. Henceforth, sooner or later the bubble was destined to burst.

RELATED ARTICLE: The mirror of development

There are three reasons for salaries or retirement payments being now lower than in 2013, if calculated in dollars. Firstly, previously considerable amounts of salaries were paid unofficially, cash in hand. Secondly, amount of national social insurance payments, which are then transferred to the retirement fund, were lowered from 36% to 22%. Finally, since 2013 the value of dollar has risen in comparison to other global currencies (for instance, the value of euro to dollar has decreased from 1.4$ to 1.1$), as well as various consumer products (it is especially the case with wheat, meat and oil products, which are cheaper in Ukraine and the world in dollars now, than in 2013).

However, despite the fact that Ukrainians did not become evidently poorer after 2013 does not eliminate the fact that they remain hideously poor, just like before 2013.

Dimensions of poverty

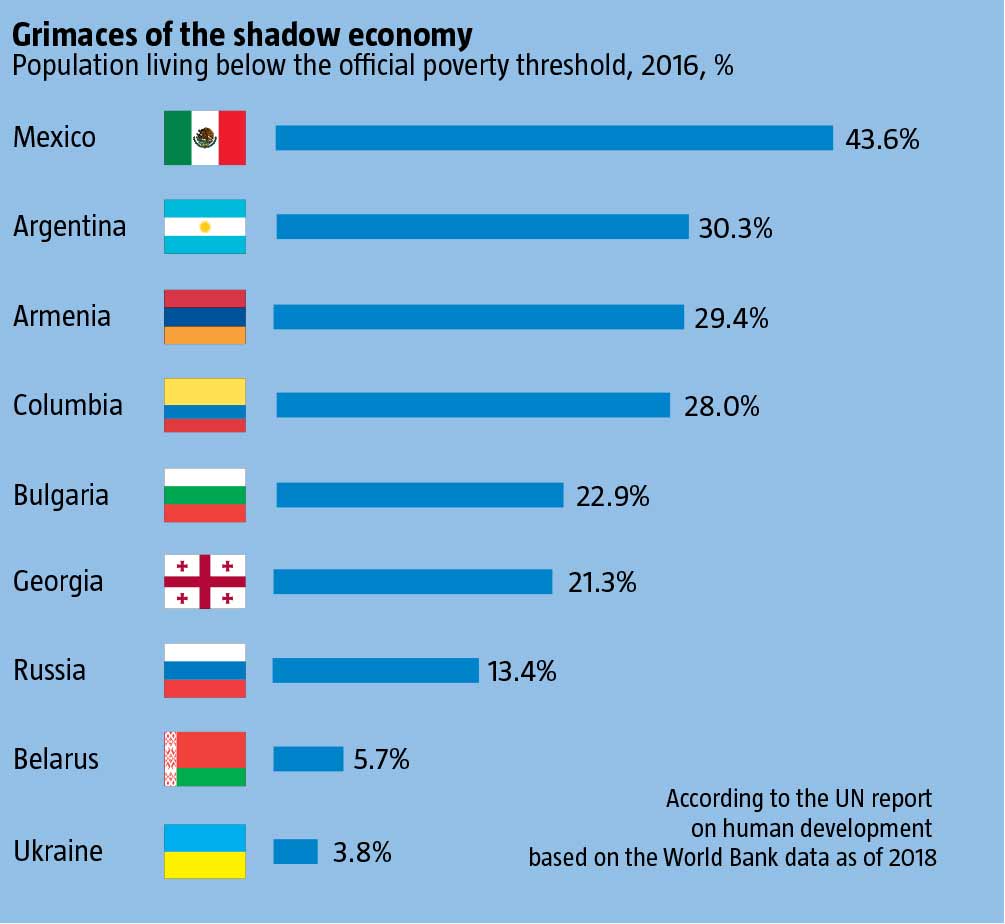

Traditional approach to researching the poverty demonstrates that Ukraine’s situation is far from being unique and its dimension catastrophic if compared to similar examples elsewhere in the world. For instance, if we look at the national measurements of poverty, that are based on the calculation of people who live on less than a minimum living wage (according to World Bank), in 2016 Ukraine only had 3.8% of such people (compared to 5.7% in Belarus, 13.4% in Russia, 22.9% in Bulgaria, 28 to 30% in Columbia and Argentina and nearly 43.6% in Mexico). In reality, this has been achieved as a result of intentional lowering the minimum living wage in Ukraine – contrary to the more realistic calculations in several other countries. At the same time, even after evaluating the purchasing power of Ukrainians, the percentage of people living below the poverty threshold still remains lower (6.4%) than in a number of European Union countries, such as Greece (6.7%), Bulgaria (8.7%) or Romania (18.5%) – let alone countries like Mexico (34.5%) or Georgia (45.5%).

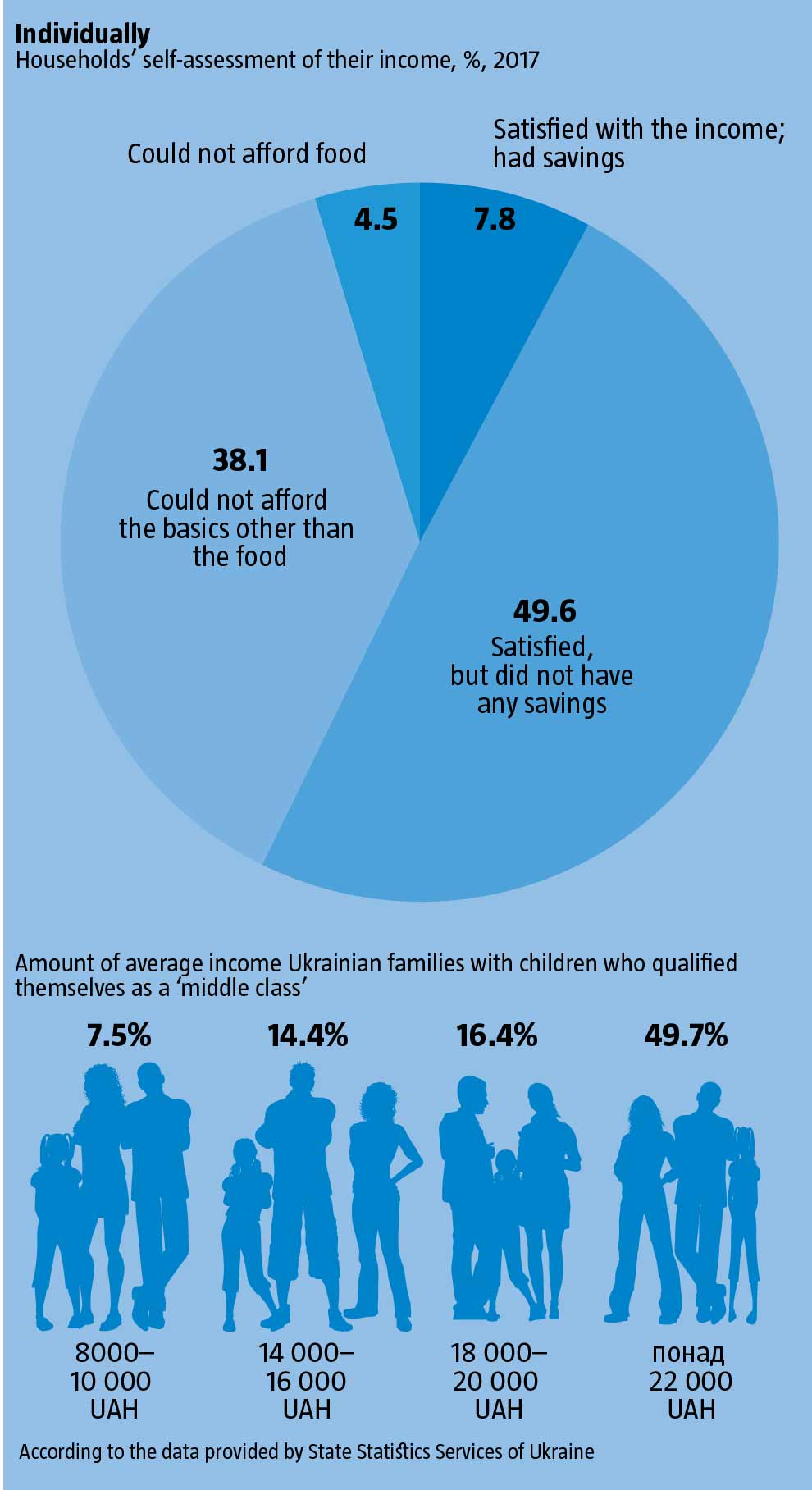

Detailed analysis of the poverty levels in Ukraine shows a different picture. According to selected data by the State Statistic Service of Ukraine (SSSU), during the first three quarters of 2018, only 1.7% of the population lived below the minimum level of income set in the state budget, while 29.3% lived below the actual poverty threshold. Those numbers demonstrate the gap between real and actual levels of poverty in Ukraine. Approximately 41% of households in Ukraine reported less than an average income per person below UAH 3,700 (i.e. minimum wage). This can be considered actual amount of Ukrainian citizens who currently live below the poverty threshold. This assumption is also supported by the other study held by the SSSU. According to this study, 42.6% out of the interviewed households claimed that they could not afford the basic goods (apart from food, and sometimes they even had to save on food).

According to the data provided by the Ministry of Social Policies, the so-called “actual living wage” in Ukraine in February 2019 was set as following: UAH 4,100 per month for the children of 6-18 years of age, 3,700 for working adults (or, UAH 4,600 before taxes), and UAH 3000 for retired people. This means that the official average salary earned by Ukrainians in February (UAH 9,200) would allow a hypothetical family, where both parents would earn this sum (i.e. UAH 14,800 after the taxes) to live just above the poverty threshold – of course, assuming that the family had only one child. In case the family had two or more children, it would push them way below the poverty threshold. Industrial sector workers also balanced on the edge – their averages household income would amount to just around UAH 16,300 (with the official estimation of UAH 15,800 to be the borderline).

Majority of the public sector workers (especially those working in education and healthcare), who only had one child, also ended up living below the poverty threshold. The average salaries in these industries amount to somewhat above UAH 11,400 and UAH 10,000 accordingly. Only those employed in aviation, IT, financial and banking sector could boast a stable income. Unsurprisingly, majority of the pensioners were living below the poverty threshold – in January this year the average retirement pension (UAH 2,650) did not cover even the 90% of the officially promised UAH 3,000 payment for the disabled citizens. The minimal payments have not even reached the 55%.

In December 2018 only 32.8% of permanent employees in Ukraine received a salary exceeding UAH 10,000 (before the tax), which has allowed them to live slightly above the poverty threshold, while raising a child. Out of those people, 41.5% were employed in the industrial sector, 25.1% in education, and another 16.3% – in healthcare sector. At the same time, 59% of the finance and banking sector employees could boast a salary of over UAH 10,000; 62.5% were in civil service and 65.6% in aviation.

Needless to say, all of the above mentioned numbers were taken out of the official government-provided data. On one hand, it is not a secret that people working in a private sector frequently receive considerable part of their salary (frequently, the bigger part) in cash. On the other hand, one should also take into account inconsistency of the official living wage in relation to the purchasing power and costs of living, especially when it comes to the prices of rent. This problem has been recently conversed about on a number.

In search of the solution

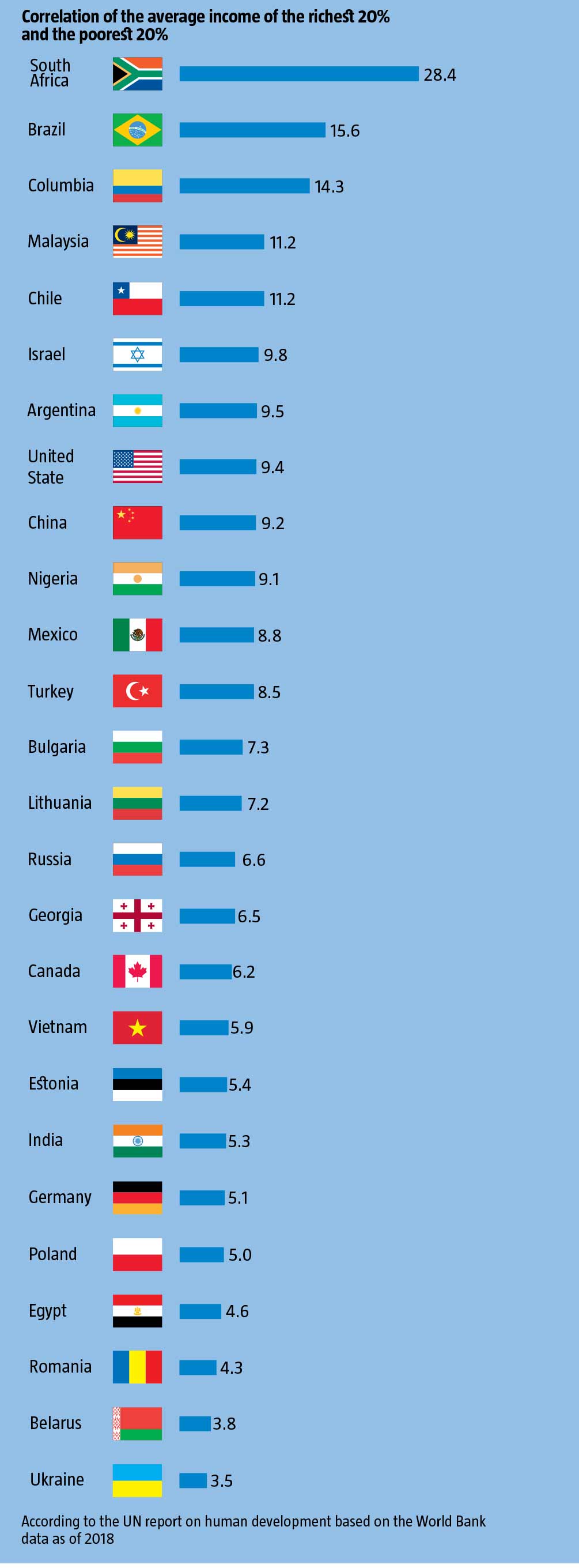

When we compare Ukraine to other developing countries, especially those which demonstrated very high economic growth, we will notice the less obvious division between the rich and the poor (see Grimaces of the shadow economy). For instance, in Malaysia, China and even Turkey the income gap between the poorest 20% and the wealthiest 20% is two or three times bigger than I Ukraine. Widening of the income gap accompanied by an accelerated economic growth is a natural process though, since the wealthy ones are able to grow their income faster, than those with less money. At the same time, owing to the economic growth, both categories become richer – even with different levels of intensity. Additionally, when we look at the income gap between 20-30% of those the poorest and of the richest ones, we will see the appearance of the small and middle-size business owners and professionals’ middle class. Polarisation of the society and antagonism between the narrow oligarchs’ circle as well as the very rich on one hand, and the poor, hardworking majority, on the other and combined with the slow economic growth may lead to little differences in income between the former and the later.

Therefore, redistribution of wealth will not provide an immediate magical cure to poverty problem in Ukraine. On the contrary, speculating on this topic will only deepen the issue. The constant threat of losing one’s wealth and assets prevents the owners from investing in long-term projects, and as a result it slows down the country’s economic development. When it comes to private property, uncertainty and persistent fear of losing one’s assets, force people to transfer their funds abroad. Ironically, when corrupt officials are hesitant to invest their funds (even laundered money) I the country’s economy, it causes more damage to the economic development than money-laundering itself – because even if these funds were laundered, they still remain in the country and contribute to the local economy. There are many examples of developing countries, which, despite the high levels of corruption, show surprisingly high levels of growth. Of course, these are hardly positive examples to follow. The fear of investment equals removal of the resources from the country’s economy.

RELATED ARTICLE: New ways to solve the old problems

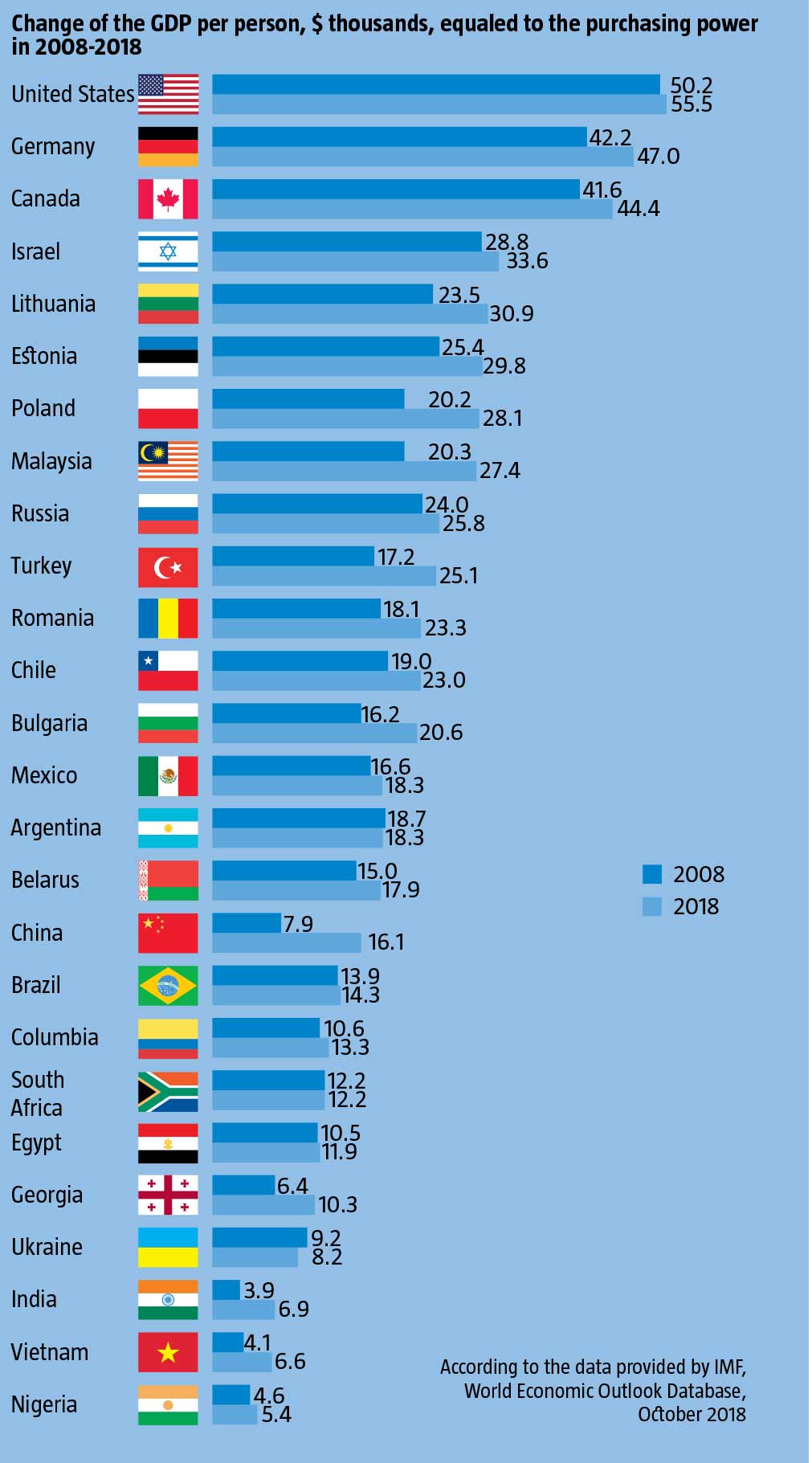

When Ukraine became independent market transformation and economy’s transition to capitalism was somehow understood by Ukrainians as an entry ticket to the first-world countries club. There was a horror of joining Latin American countries, or, as many have feared, Asian or African countries. Curiously though, many countries of the former Soviet bloc have more in common with those Latin American, Asian or African countries, rather than the developed West. Many people in Ukraine failed to understand that the quality of life in the rich countries does not automatically come with the market economy, but is a result of a successful complex economic strategy. In Ukraine economic growth has never become a priority for the policy makers. In 2004 Ukrainian GDP per person amounted to USD 6,300 (compare Poland – USD 14,100; Romania – USD 11,500) and in 2018 – USD 8,200 (again, compare these numbers to USD 28,100 in Poland and USD 23,300 in Romania). Recently, Ukraine has been left behind some Latin American and Asian countries – despite the fact that traditional stereotypes consider the very comparison to those countries somewhat humiliating. For instance in 2018 Ukrainian GDP was two to three times lower than in Malaysia (USD 27,400), Chile (USD 23,000), Argentina (USD 18,300) and Mexico (USD 18,300).

Ukraine was left behind even those countries which used to be considerably poorer in the past. For instance, Ukraine’s current GDP fell way behind Egypt (USD 11,900), Colombia (USD 13,300) and China (USD 16,100). At the moment Ukraine’s development is comparable to the one of India (USD 6,900), Vietnam (USD 6,600) and Nigeria (USD 5,400). Those countries’ GDP was twice smaller than Ukraine’s just ten years ago, on the eve of 2008-2009 financial crises. Additionally, their economies grow several times faster than the most optimistic scenario set for Ukraine.

Past experience of poor countries prove that the only way to fight the poverty is to grow and increase national resources and national wealth. By no means should this be done via the so-called re-distribution of wealth. Ukrainian small and middle size enterprises as well as the state should play the key role in this process. It is the state’s responsibility to support the businesses already in operation and encourage creation of the new ones, as well as to support citizens’ business initiatives. To work and to take a risk must be a prestigious and protected task, safe from the corporate raiding and legal injustice. Property rights and the ability to ripe the benefits of one’s hard work should be protected not only from the authorities power abuse, but also from the populist initiatives of various politicians, who are calling to “get hold of what does not belong to you”. Otherwise, the country will never be able to break the vicious cycle of progressing poverty and recession.

Ukrainian middle class was formed as a result of continuous confrontation with the alienated oligarchic state and henceforth has always wanted to minimise the contact with the state. However, the future of bourgeoisie and the necessary changes depend on the ability to leave behind the disagreements and rejection of the state and turn it into a tool of its own policies. Avoiding taking responsibility and failing to take an initiative will create a “life isolated from the state”, which will ultimately be terminated by the state as such – this time by forces that are in conflict with the middle class. It will either be the current corrupt oligarchic conglomerate, which controls the state system regardless of those who are formally in power. It may also be the newly formed populist forces, which will aim to establish the “strongman” dictatorship. Taking initiative and leading the way is the only solution for the middle class. Only decisive actions and not the weak efforts to hide behind the scene will lead to the positive changes in the country.

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook