The economic system in Ukraine today is very fragile. It faces several challenges and threats. This is very much the results of more than 20 years of bad economic policies and inadequate institutions introduced in the country during what we call “the first transition” which was supposed to bring about a market economy and liberal democracy, but moved Ukraine from a planned economy to an oligarch type of economy instead.

This was caused by a number of factors: the lack of a strategy in the 1990s and 2000s, which would give Ukraine the prospect of EU membership along with other Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC); strong connection with Russia, which dominated the economy and politics of the country with advantages for Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs only; uncontrolled and ideologically biased implementation of a transition strategy from planned economy towards market economy, which was wildly ruled by a handful of people in dominant position from former nomenclature and business; and the lack of social cohesion which would boost unity among all people in the country.

RELATED ARTICLE: Tycoon Wars: Elusive Hope

The first transition: from planned economy to the oligarch system

The social cost of this “first transition” in the past 20 years was huge in terms of poverty, inequality, life expectancy migration and reduction of living standards. One of the most telling variables that reflect it well is the demographic trend (see The decline of life expectancy in Ukraine during transition). Ukrainian population has declined dramatically from over 51 to less than 46 million people in two decades, a phenomenon never observed in a country in time of peace.

Life expectancy reached the highest level in 1970 (70.24 years), and remained stable around 70 years during the 1980s. During the first phase of transition in the 1990s it collapsed to 67 years, and then increased slightly again, to reach, in 2013 the same level which was reached by Ukraine already in 1970

Source: UNDP

POLAND AND UKRAINE: TWO DIFFERENT STORIES

What made Ukraine’s performance during this “first transition” so poor in comparison to Poland? The answer has to be found in the institutional transformation of the two countries and in particular in the fact that the change in Ukraine was driven by politicians turned oligarchs, controlling both politics and economics. In Poland it was driven by the European Union conditionality. Market economy was the target for both countries, but institution building in Poland followed a path suggested by the EU, including anti-corruption laws, anti-monopoly authority, EU supervision for reinforcement and implementation etc. In Ukraine the change was driven by the interests of the main groups dominating the economy and by the former nomenclature, which in turn dominated also politics, i.e., the oligarchs. The role of oligarchs in Poland was very limited, and former nomenclature failed to gain control thanks to Solidarność, the well-known trade union movement that emerged and grew into opposition leadership in the 1980s.

Source: EBRD

In 1990, Poland and Ukraine had similar initial conditions, measured as GDP both per capita and in absolute terms. After the 1989-1992 recession, Poland saw growth that allowed it to outrun Ukraine. 20 years later, Poland saw its GDP in absolute terms and purchasing power of income grow while Ukraine lagged behind in both aspects

Ukraine also lagged behind all EU New Member States (NMS): it had not started its transition until 1992, which was relatively late. It went through a deeper and longer recession: not until 2000 did Ukraine see positive economic growth, yet quite unstable one (see GDP growth in NMS and Ukraine 1990-2013). Finally, the global recession of 2009 was more pronounced in Ukraine than in the NMS (and in many other countries in the world), reaching about 15%. As a result, Ukrainian GDP in 2014, after 25 years of transition, was the lowest among all transition economies (100 taken as the 1989 GDP).

Source: own estimates based on EBRD data

Levels of real GDP in 2014, in 2008, and in 2004 (1989=100)

The most important economic changes and institutional transformations which characterized the 1990s in Ukraine were privatization of state assets and distribution of property rights (a key institutional change that occurs in general in transition to market economy). Privatization in Ukraine turned political groups into clans with opposite economic interests, fighting for accumulation of assets rather than for ideal models of privatization and ideas for political and economic change.

In theory, transition to market economy also requires liberalization and free prices, and elimination of strict price controls, so that the market can set them through free competition, relying on real value of goods and their supply and demand. The practice of market rules was not known in most of Former Soviet Republics (FSR), including Ukraine. Therefore, the benefits of privatization went only to people and agents who had more information and strategic positions. These included former nomenclature, oligarchs, those involved in the oil business, the mafia etc. This phenomenon existed in all FSRs to a certain extent, but Russia and Ukraine were the particular enigmatic examples. Both have more oligarchs today than virtually any other country in the world. Property rights were not simply acquired through legal and normal procedures. Clans, organizations, families and oligarchs fought with each other for more individual rights and specific benefits. Eventually, mass privatization failed to serve the idea of distribution of property rights to everyone in pursuit of economic democracy.

RELATED ARTICLE: A Burden on the Economy

The vacuum of power was lethal in terms of the miss-distribution of property rights. The lack of fair, efficient and transparent bureaucracy was one of the major problems. It failed to ensure a fair privatization process, but allowed it to slip into chaos and, given the lack of anti-trust organizations, to result in the concentration of power in the hands of few officials inherited from the Soviet regime.

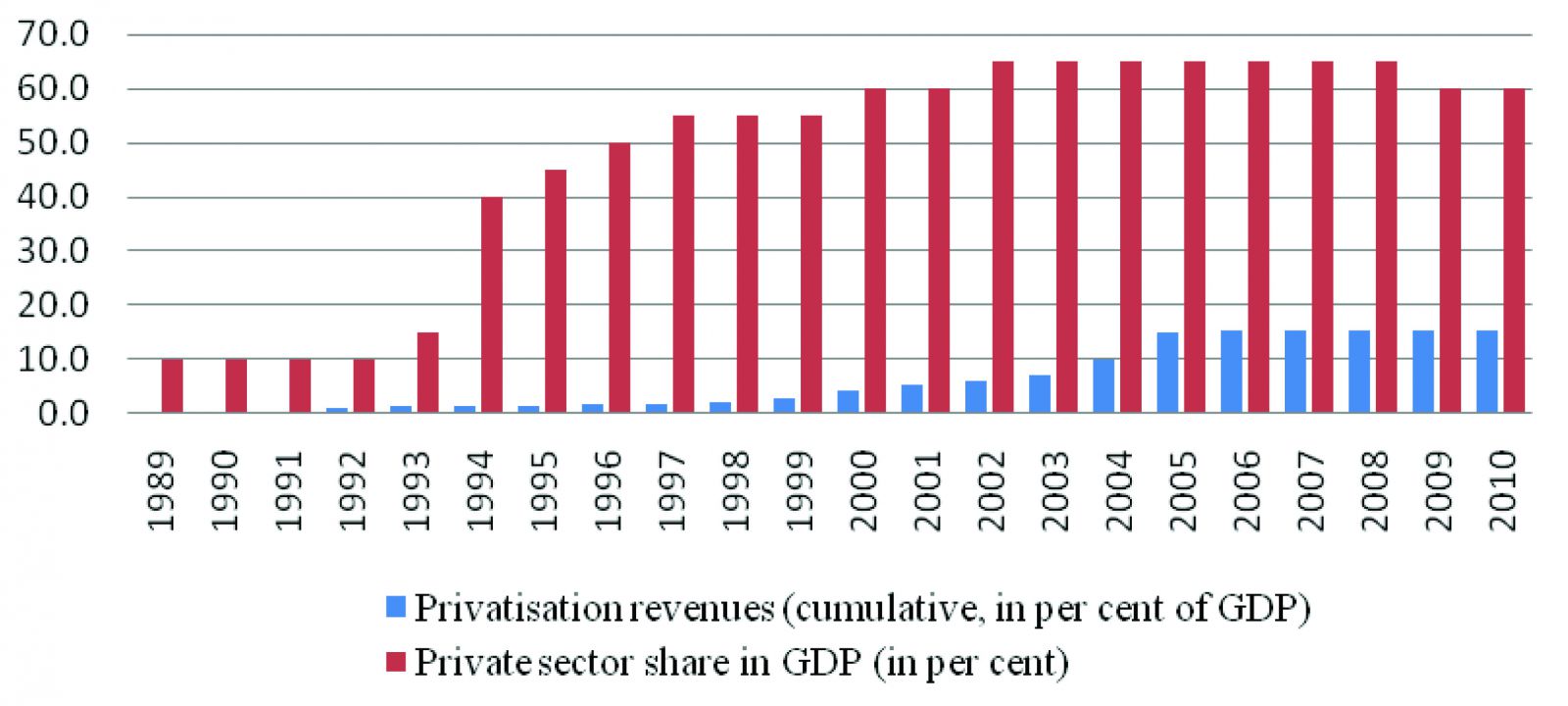

Private sector accounts for around 60% of GDP in Ukraine today (compared to the average of 75% in EU member-states and 70% in NMSs). According to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), Ukraine received just a small fraction of the worth of assets actually privatized in revenues from privatization. In Poland, this share accounted for about 30-50% of GDP in the 1990s (see Ukraine: privatization and private sector, % of GDP).

Source: EBRD, Transition Report 2013

The chaos and the vacuum created during the “first transition” in Ukraine were deeper than in other CEECs, and it lasted through all the three phases of transition and of privatization listed above. This is for a number of reasons. Firstly, Ukraine not only was giving up the planned system, but it was obtaining its national independence for the first time. Secondly, a handful of people concentrated political power and monopolized national assets in their hands. Thirdly, and probably most importantly, EU membership option was not considered viable at the beginning at all. Instead, Russian influence was still predominant and economic strategy that was put in place was a typical “post-soviet” political-economy strategy where political elites become oligarchs and rule the country directly or indirectly.

The rise of tycoon clans

The oligarchic system in Ukraine began to be formed immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but it was finally established firmly in the second half of the 1990s, during the presidency of Leonid Kuchma. The three main oligarch clans that emerged to dominate the Kuchma’s presidency represented the main regional clans of Kyiv, Dnipropetrovsk and Donetsk. They had also dominated and ruled Ukraine in the Soviet time. In a country with weak financial and economic institutions, these clans easily took control over many former state-owned enterprises, buying and privatizing national assets at the low prices. Subsequently, the new institutional framework in Ukraine was shaped to fit their preferences and interests. A situation where prices were not set by the market but were subject to the interests of dominant groups soon became a reality. As a result, the whole economy is reckless, production is inefficient and obsolete, markets are monopolized and jeopardized. Markets are controlled by few people, and are far from being competitive or fair. So, Ukraine’s private sector today has a lot of obstacles and has limited impact on abstract mechanisms of market economy, such as regulation of the demand/supply balance. Inequality has increased dramatically, while social mechanisms of income distribution are completely absent.

RELATED ARTICLE: A Road Map for Economic De-Sovietization

This has aggravated regional differences and political fragmentation, further weakening social cohesion of the country and creating threats to the unity of the country.

Source: own estimates based on data from World Bank (GDP) and Forbes World's Billionaire List (Korrespondent for the rating of 50 richest people in Ukraine)

The lack of an efficient legal and institutional framework that could prevent this distorted informal behaviour, resulted in corruption that emerged furiously in the 1990s and accompanied Ukraine in the past two decades. It is a necessary component of the oligarch system. This level of corruption also underscores a very low level of civicness and social capital (as described by Robert Putnam, an American political scientist), i.e. low participation of civil society in the political and economic system.

Source: Transparency International

Note: Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) scores and ranks countries based on how corrupt a country’s public sector is perceived to be. It is a composite index, a combination of surveys and assessments of corruption, collected by a variety of reputable institutions. A country’s score indicates the perceived level of public sector corruption on a scale of 0-100, where 0 means that a country is perceived as highly corrupt and a 100 means that a country is perceived as very clean. A country's rank indicates its position relative to the other countries/territories included in the index.

In 2010, Ukraine ranked 134 out of 177 countries measured. In 2013, it dropped to 144 out of 177. Increasing perception of corruption was not the only issue. Resources wasted by companies in some former Communist economies (NMSs and Ukraine) on bribes to public officials for getting “things done” were another problem (see Informal payments to public officials). In Ukraine, corruption increased dramatically after 2009, while in NMS, affected by EU conditionality and the need to get EU funds, corruption decreased constantly, before and after enlargement in 2004/2007. The reasons why corruption is still growing in Ukraine after 2009 may be due to three factors: the return of ex-President Viktor Yanukovych and his clan to power, in 2010, with a consolidated system of informal payment and the vicious circle between business and politics, oligarchs and politicians; the crisis which made business more difficult, and economic relations more reliant on informal payments rather than the rule of law; and the weakening of Ukraine’s EU membership prospect during the rule of the Yanukovych regime, which contributed to loosened conditionality and reduced transparency.

Source: World Bank

FDI and trade: new hopes for a “second transition” towards the EU

The Ukrainian “first transition”, or better to say, the abandonment of the planned system, did not follow a stable transformation path from the planned economy as the defined point A to the market economy as an undefined point B. On the contrary, it had been unstable from the very beginning: institutional reforms were delayed, although the market was introduced suddenly and prices were liberalized immediately, and privatization was launched. It should be also clear that the transition in Ukraine was a complete failure for the economy, although several economists have argued for the opposite.

From the very beginning, the Ukrainian transition had been characterized by two important criteria which made transformation unstable and uncertain: the choice of possible EU membership on the one hand, and strong relations with Russia which influenced and de facto limited Ukrainian independence from the very beginning. By contrast to Ukraine, all CEECs had from the very beginning chosen to be part of the EU, and advanced their candidacy to the EU immediately after the fall of the Berlin Wall. It took Ukraine much longer, not until the Orange Revolution of 2004-2005 at least, to make its steps towards EU accession. However, even after the Orange Revolution the Ukrainian government and parliament failed to bring about real steps for Ukraine’s EU integration because of “internal feuds” and clan conflicts. When Viktor Yanukovych and his clan won presidential election in 2010, the country’s vector of partnership was in favor of Russia.

Benefits of EU membership

Economically, EU membership would have been a guarantee for foreign entrepreneurs encouraging them to move their capitals and start businesses in Ukraine. As it happened in other CEECs, in particular during the process of accession preceding actual membership in the 1990s and 2000s, huge flow of Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) could have come to Ukraine. Without it, Ukraine lacks new capitals and technological assistance which would be useful to restructure its 1970s obsolete production chain. With the prospect of EU membership, Ukraine would have gotten advantages not only in terms of capital and innovation, but also in terms of political stabilization, freedom from oppressive and monopolistic oligarch capitals, safer economical environment, fair contractual guarantee for investors, lower country risk, and secure economic relations.

RELATED ARTICLE: Investing in Ukraine’s Future: Removing Barriers to Open Opportunities

In the 1990s and 2000s, many multinationals invested heavily in CEECs, helping them build competitive advantage based on lower labor costs, skilled labor force and marketing positioning. All this can be perfectly replicated in Ukraine. FDI inflow to Ukraine could increase its trade flow with the EU. These two factors, FDI and international trade, could be the key factors to spur further development of the Ukrainian economy. Still, opinions vary on this. Some economists argue that FDI boost commercial deficit because foreign investors import capital goods, technology and other services from their own country in massive amounts. Moreover, FDI and trade could increase inequality within the country since new investments would use skilled labor and pay differentials would increase. However, despite these potential threats, in this particular case of Ukraine with its oligarch-dominated economy, strong connections to distorted trade with Russia, domination of obsolete industrial goods and natural resources, integration into the European economic system (followed by the inflow of FDI and intensification of international trade) would be a better choice for the country.

In the past years, FDI from the EU to Ukraine have increased, exceeding those from Russia or any other country. This is a good signal for future relations between the EU and Ukraine (see Volume of FDI in Ukraine). Paradoxically, about 30% of total FDI come to Ukraine from Cyprus. This is due to the particularly easy tax policy applied to foreign capitals in the Cyprus jurisdiction. Most of the Cyprus FDI in Ukraine are investments from oligarchs who first go to Cyprus to avoid taxes and to be “cleaned” from dirty business, and then return part of this capital to Ukraine as FDI with the possibility to gain further profits there. However, despite this “fake” FDI from Cyprus, the investment position of Europe is still ahead the Russian one.

Source: Ukraine’s State Statistics Committee

According to the 2007 estimates by the Economist Intelligence Unit, in 1989, Russia counted for 33% of Polish imports and 28% of exports. Today, Germany has replaced it, counting for 38% of Polish exports and 27% of imports. In 2007, a few years after Poland joined the EU in 2004, only 5% of Polish imports came from Russia, and 2.6% of Polish exports headed there. This pattern is similar to other CEECs

Similarly to CEECs, Ukraine would see its trade pattern change as a result of integration with the EU system. Today, it is mainly oriented at Russia. Poland, now the biggest economy in Central and Eastern Europe, offers a good example of a similar pattern changed.

Therefore, the main challenge Ukraine is facing today, on the verge of its “second transition” as far as trade and changes in production are concerned, will once again involve the role of oligarchs. It is twice more difficult than what CEECs had to go through for two reasons: it requires political change, and politics, as said above, is controlled by oligarchs. Moreover, the big companies that need to change the structures of their production and orientation are owned by these same oligarchs who dominate politics and who would thus be the ones in charge of changing the rules. This vicious circle could only break under strong pressure of civil society that should influence both further changes in the upcoming parliamentary elections, and the political agenda of the current President who was elected thanks to the support of EuroMaidan protesters.

Economically, the new Ukrainian model will involve the possibility to export products that have higher technological component and added value during its “second transition” towards the EU. Moreover, EU membership requires continuous investments in innovation and organization to ensure the ability to compete with old European firms. For Ukraine, this also means the restructuring of the agricultural sector which has high employment (around 18-20% of the workforce) but lower productivity (the agricultural sector generates a mere 8-9% of GDP). In addition to that, big former state-owned enterprises will have to go through restructuring and attract foreign capital by forming joint ventures to innovate and foster productivity.

The EU will play the main role in the import-export flow with Ukraine, and the trade pattern is slowly changing already (see Ukrainian exports and imports: main partners). So far, the EU has removed most of its tariffs for Ukraine exports, in order to favour Ukrainian business during the shock which is been caused by the military and trade conflicts with Russia in the framework of the Eastern Partnership programme between the EU and Ukraine. At the same time Ukraine found new commercial partners in China, Turkey and Egypt (according to Ukraine’s State Statistics Committee, Ukrainian exports to these countries has grown from 11% in 2011 to 17% today).

Source: International Trade Center

Policy suggestions

This analysis is rooted in political economy and draws conclusion and lessons which are based on the three factors that caused the failure of the Ukrainian economy in the period of the first transition. In order to boost its economic development, Ukraine now needs a radical change based on three strategic objectives: the goal of EU membership, the removal of oligarchs from politics, and economic independence from Russia.

The EU membership should be a priority mostly for strategic reasons, not purely economic. Such a prospect would break the interdependent “strategic policy triangle” so far followed by the Ukrainian ruling class and composed of the three pillars: non-EU membership, dependence on Russia, and rules of the oligarchy. It would serve as an important conditionality against oligarch interests and corruption, help restructure the economy, particularly that of Eastern Ukraine dominated by obsolete heavy industry where the interest of oligarchs are intertwined with those of Russia; and integrate Ukraine’s economy into the European space, rather than into Russia’s, introducing innovation and technological progress, and pushing the country towards a higher technological frontier and a demand-driven growth.

RELATED ARTICLE: Ukraine’s Robber Barons: Where They Come From?

Russia used to be Ukraine’s main commercial partner , both in imports and in exports. The “second transition” should change this: trade with the EU will brings higher added value and boost Ukrainian productivity since the European market is more dynamic and more advanced than that of Russia. However, this means that Ukraine will have to restructure most of its firms, especially those located in the East. The latter will have to switch their production towards cleaner and more sustainable forms, and become more technologically advanced. The change will require new skills, and will bring about higher productivity gains, since new production would be more capital intensive and equipped with more advanced technology. As seen in Poland, this is difficult but not impossible to do.

However, policy makers need to be careful and take into account international constraints: trade deficit should be kept under control in order to avoid further devaluation of the hryvnia. It is a priority to use national resources to import capitals and machinery rather than consumption goods. Moreover, a devaluated hryvnia could benefit Ukrainian exports and could protect, for a while, a new infant industry within a framework of an import substitution strategy similar to the ones used in many East Asian countries during their development stages.

Possible negative effects of stronger EU competition and more efficient EU firms on inequality and unemployment (resulting from closing down and bankruptcies of inefficient Ukrainian companies) caused by the entrance of EU firms in Ukraine could be coped with through social institutions that guarantee minimum wages for unskilled workers and subsidies for big yet obsolete Ukrainian enterprises. Even if less efficient compared to their European competitors, these enterprises could still value added and absorb large part of employment, hence they could deserve temporary protection. Europe would easily accept a transition phase for Ukraine where these subsidies in the forms of state aid still persist.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Ex-President’s Baggage

Another crucial element in Ukraine’s new “second transition” will be the role of FDI, mostly from the EU. It could contribute to the breaking of the oligarch-dominated system, and guarantee the distribution of growth and social benefits of development that would boost social cohesion and political unity.

Meanwhile, remaining distant from the EU and delaying the beginning of the membership process indefinitely would result in a Ukraine that stays closer to Russia and is subject to the oligarch economy and rules. Today, the approach of the new Ukrainian government and President seems to have changed towards EU membership.

However, the crucial role in this “second transition” should be played by the civil society which strongly emerged during the protests between November 2013 and February 2014. The radical change, key to changing political economy of the country, strongly depends on the prospect of politicians and oligarchs feeling watched, controlled and dismissed by the civil society if necessary. This political game, in turn, will depend very much on the level of social capital and trust that it is possible to find in society, as many economists have already argued. Social capital is weak in Ukraine, as in other former Soviet countries. However, it is not unchangeable, but can be reproduced and increased. This occurred in Ukraine during the mass protests which may have helped “glue the society together”, at least in most of the country.

Authors

Iryna Zhak, Parthenope University of Naples, Italy

Pasquale Tridico, Roma Tre University, Rome, Italy

Mr. Tridico is the author of the book Institutions, Human Development and Economic Growth in Transition Economies. He is soon visiting Kyiv to present it to the audience in Ukraine