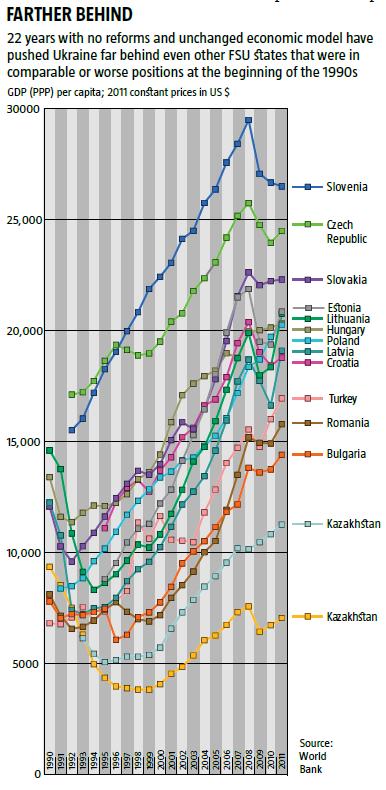

Twenty-two years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine’s economy remains a fragment of the “single national economy”. Any attempts to manually adjust it to meet the needs of the global market have increasingly pushed it farther behind. Now, Ukraine is dragging far behind other FSU states that were in comparable or even worse positions at the beginning of the 1990s. Ukraine’s current per capita GDP is 21% below its 1990 rate despite a 13% decline of the population since then, while states that have implemented minimal reforms have improved immensely since the 1990s. Ukraine’s economic predicament has led to the rapid impoverishment of the majority of its population and left millions unemployed (over 7 million including hidden unemployment, according to The Ukrainian Week’s estimates). Many Ukrainians – at least 1.5 million – are forced to seek jobs abroad, making labour a major Ukrainian export commodity and a means for the government to patch holes in the budget. In 2012, Ukrainians working abroad transferred USD 3.7bn home. Obviously, Ukraine’s economy will never grow at a high and sustainable pace with the socio-economic model inherited from the USSR in place. The country needs a profound reboot to unlock its potential. Ukraine has to shed its status as a raw material colony and switch to a sustainable economy based on natural and geographic advantages and high value-added industries.

A SUITCASE WITH NO HANDLE

Inefficient structuring is hampering the economy’s autonomy. Firstly, it is over-integrated with other post-Soviet economies, especially that of Russia (in the engineering and military industry in particular). In 2012, 39% of Ukraine’s total foreign trade turnover was with the CIS, over ¾ of this with Russia. This is the effect of a Soviet-era policy whereby facilities of one production chain were dispersed in different republics to prevent their separation. Secondly, the structure of physical capital in Ukraine is completely determined by the Soviet economy. Its capital assets are energy and labour inefficient. According to the World Bank, Ukraine consumes 3 to 4 times more energy per dollar of GDP than most developed countries. The USSR had vast resources and fuel production capabilities and there was no emphasis on energy efficiency, hence the energy-consuming PP&E. With full employment as the Soviet government’s top priority, its plants were designed to provide full employment rather than efficiency. The impact of this policy is still visible in huge fuel imports and overblown staffs that are willing to work for peanuts. Thirdly, a high concentration of production facilities created numerous monotowns. Today, these remain the only source of survival for many thousands of Ukrainians who have nowhere else to go when output plummets at their factory or lay-offs take place as a result of technological upgrade or bankruptcy. One recent example was the series of massive protests in Lysychansk, a monotown in Luhansk Oblast where a slew of the town’s major factories closed down one after another (see The Looming Revolt in Lysychansk).

Another systemic problem that Ukraine inherited from the Soviet era is the government’s excessive role in the economy, which even constitutes a monopoly in many sectors. It generates 35% of the country’s GDP in production and 45% in aggregate demand, i.e. 50-60% of GDP turnover through demand or supply. Coupled with inefficient state-owned enterprises, this creates extensive opportunities for corruption. The government sector is the largest source of enrichment (through budget funds, power and state monopolies), so it attracts “entrepreneurs” who focus on building shadow scams. Another element of this problem is the population’s financial dependence on the state. With nearly 14 million pensioners and 7 million public sector employees, plus their families, over half of all Ukrainians rely on the government financially to some extent. This ruins their motivation. Most people who end up employed in the public sector lose competitiveness in a labour market. Also, there is a problem of mental state-dependence inherited from the USSR. The Bolshevik regime used paternalism and stifled private initiative to destroy the remnants of the private-ownership mindset that had been typical for most Ukrainians in contrast to the community-oriented Russia. The effect of this policy is clearly visible today as many Ukrainians still expect the government to solve their problems – even daily ones – while refusing to seek solutions or improve their lives on their own. All this fuels political populism, opportunism, deep disenchantment and overall political uncertainty.

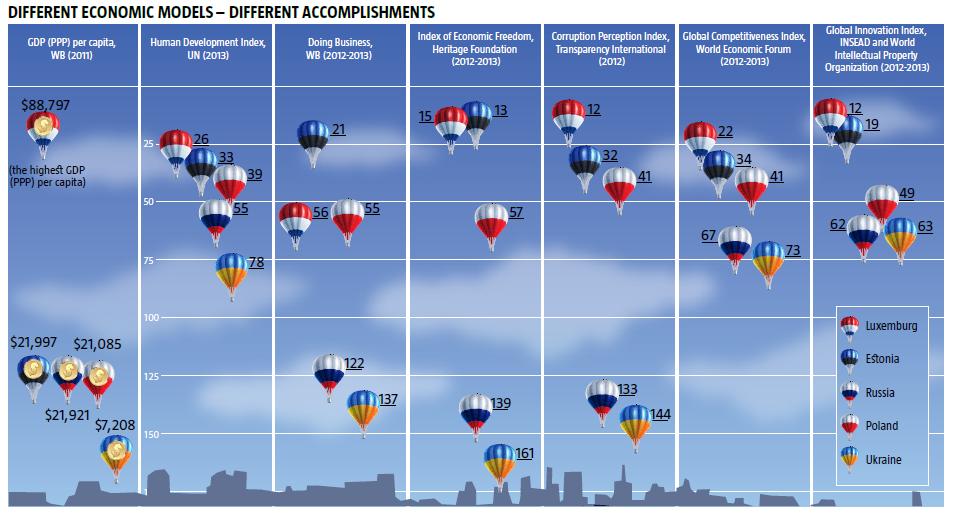

This explains why market institutions are appallingly weak. The 2012-2013 Global Competitiveness Report provides a vivid example: Ukraine ranks 73rd overall, and 132nd in the Institutions category. It lacks effective performance in two key market institutions: private property and freedom of entrepreneurship. The inefficient judiciary, made so by corrupt judges who also depend on those in power, cannot protect private property. The dependence of businesses on numerous government authorities that make up the core of the current system (i.e. the tax administration, law enforcers, sanitary control, licensing authorities, etc.) distorts freedom of entrepreneurship. In fact, it is the weakness of these two market institutions in Ukraine that makes doing business a challenge (and numerous rates prove this – see Different economic models – different accomplishments). While business obtains lower profitability, it accumulates more and more risk factors, including the potential for total loss of business through raider attacks. This is one of the key reasons behind the overwhelming deficit of investment and the slowdown of investment growth (in 2012, Ukraine saw UAH 257bn in gross investment, nominally 4.7% below the 2011 rate). A slew of other market institutions remain underdeveloped. These include anti-monopoly policy (ironically controlled by the very oligarchs whose monopolies should be affected), labour legislation, entrepreneurship assistance. This leads to deep distortions in doing business because a handful of oligarch monopolies effortlessly rake in huge profits while those who opt for entrepreneurial skills and innovations struggle to stay afloat.

Ukraine also inherited a distorted system of motivation from the USSR in which business initiatives are stifled rather than encouraged. With rules that frequently change for non-oligarch businesses, a high risk of losing one’s business under pressure from government-linked competitors, and burdensome bribes, entrepreneurship is made unprofitable and private initiative redundant. Meanwhile, opportunities for rapid enrichment in the government distract potential entrepreneurs, encouraging them to struggle for power by grabbing available public assets and monopolising markets. The government blames its problems with pension and social benefit payments on entrepreneurs (not oligarchs!), thus artificially shaping their negative image in the eyes of society. For instance, the 2010 Tax Maidan protest faced negative reactions from public sector employees after pro-government mass media outlets criticized it.

READ ALSO: The Illusion of Big Business

The system is also killing initiative amongst salaried employees, most of whom are discouraged from improving their performance. The key reason for this is the low level of compensation in an oligarch-controlled economy where unemployment is soaring. The resulting excessive competition for jobs allows oligarch businesses to keep salaries sustainably low. Non-oligarch businesses can’t afford to offer their employees better salaries because higher labour cost will make them unprofitable. The government can only afford to raise salaries a mere UAH 50-100 per year. This policy forces people to focus on extra sources of income rather than their main job. Hence, Ukraine has one of the lowest workforce productivity rates in the world. Very often, especially in the public sector, quality and productivity do not matter at all. The top priority is to collect money at the bottom and transfer it to the top, so professional productivity is out of question. Another side of the problem is that sometimes, the administration views initiative as potentially threatening to its own longevity, so it stifles or punishes it. This distorted system of motivation is the worse element of Ukraine’s Soviet heritage because it may take generations to correct on a national scale. The lack of motivation results in meagre workforce productivity, professional degradation in more corrupt sectors (judiciary, law enforcement, health care, education and the like), and a reluctance to pursue higher education within a system where one can simply pay a bribe to get a job. Among other things, this affects the minds of the younger generation – hence the increasing number of applicants to tax academies or law departments that open the doors to corruption-friendly jobs.

The negative impact of the Soviet legacy would not have become this critical if the government had taken consistent efforts to eliminate it. However, two decades without reforms not only aggravated the problem but led to new negative effects that are often much more dangerous. Ukraine has ended up with an oligarch-slave economic model. Ukraine’s capitalist bigwigs are not the key issue (although there could be more investment if they were foreigners). The issue is that they do not develop their businesses and do not create jobs. Instead, they redistribute what is already available and pump profits out of Ukraine. Offshore “foreign investment” by Ukrainian oligarchs is most often used to buy pre-existing assets at discounted prices through corrupt officials, including those at the very top. Meanwhile, they barely invest in the intense development or modernisation of functioning businesses. The latest news of what is now widely advertised by the oligarch-controlled mass media as the “national business” is the purchase of UkrTelecom, a national telecommunications monopoly, by Ukraine’s richest steel tycoon Rinat Akhmetov at the blatantly rock-bottom price of EUR 1bn. Shortly after, the government signed a memorandum with steel oligarchs to support their “loss-making” industry and modernisation of their plants at the expense of the rest of the economy and taxpayers. Any real modernisation is unlikely (this assumption is based on previous state programmes to modernise the steel and mining industries over the past 20 years that had no visible impact). Instead, privileges will most likely be used to further launder money to offshore zones and subsequently buy the remaining state assets for peanuts. This is the way of the oligarch-controlled economy. By contrast, an adequate economy where the capital of the richest people would create new jobs results in higher competition for the workforce and better life standards for the population.

READ ALSO: Investment Ultimatum

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

In order to get on a path to sustainable development, Ukraine has to shed its devastating Soviet heritage and the distortions that have been stifling its economy for the past two decades. This is the only way to accomplish robust economic growth and improve living standards. Key priorities include the protection of private ownership, freedom for the business environment, effective anti-monopoly policies, incentives for SMEs, and the facilitation of a high share of investment in GDP. An important prerequisite is the government’s careful strategic choice of industries to support – those that have the potential to become drivers of the economy, create jobs quickly, and boost GDP by switching from export-oriented production facilities to the domestic market as well as winning advantageous niches in global workforce distribution. This should be driven by efforts to maximise the added value of Ukraine’s products and minimize dependence on imported raw materials and fuels from uncertain sources such as “Eurasian” post-Soviet states.

To increase GDP (PPP) per capita from the current USD 7,000 to at least USD 20,000 (as Ukrainian neighbours have), capital goods that generate 2/3 of this new level of GDP should be built from scratch and outside industries with excessive capacities like steelworks, chemistry and the like. The roadmap to drawing investment is well known and has been tested all over the world. In addition to the rule of law and protection of private property, the government should minimise, formalise and depersonalise contacts between businesses and government officials. Fewer contacts through inspections, declarations, certificates and licenses mean fewer loopholes for corruption. Officials should have shorter deadlines for consideration of any requests or applications from entrepreneurs. They should facilitate business development and get adequate compensation for this rather than taking bribes for granting the right to do business. The government should open the country to international business and facilitate entrepreneurial initiative within the country by training and consulting business owners, reimbursing part of the interest on loans, designing a programme to make loans considerably cheaper, and so on.

READ ALSO: Imperial-Soviet Feudalism

Extensive privatisation is also a priority. If the public sector is the domain of inefficiency and corruption, its reach should be limited. Thus, privatisation should be completed to bring the share of enterprises associated with the state in the GDP down to 10-15%. The number of officials should be reduced while requirements and reward for them increased. Meanwhile, the scope of functions performed through the budget should be narrowed to that of a market economy. Subsequently, the government should focus on economic priorities determined by the country’s situation and stage of development. It should maintain a macroeconomic balance that is in line with the global situation and set liberal and equal rules for business. Those in power should ease and level out fiscal pressure on businesses by cutting tax rates, tax advances and non-reimbursed VAT, making inspections shorter and less frequent, etc. They should eliminate shadow exports of capital through tough tax control over transfer pricing and other offshore schemes. However, these measures should primarily target oligarch businesses, while the current government-sponsored draft law on this suggests excluding steel and mining plants from its scope.

Another important objective is to set economic barriers for costly productions and incentives for new efficient enterprises. The government could compensate a portion of expenses for every business that improves its efficiency and creates new jobs while preventing abuse. It should embark on strategic planning and understand which industries should be developed given their potential. It should also bring public investment down to a minimum: the long evolution of capitalism proves that private investors are by far the most effective.

Shattering the oligarch model will be the biggest challenge. Oligarchs hold powerful leverages in the economy, government and society. If they are removed manually, new ones will soon replace them. Thus, the government must counterbalance them. The fastest way is to draw Western investors by selling the remains of state-owned assets to them and helping them to open new enterprises, including in oligarch-dominated domains. This would use the market itself to eliminate such monopolies. Meanwhile, oligarch influence on SMEs and foreign business should be eliminated. Oligarchs should be deprived of opportunities to stifle competitive business by exploiting government authorities and monopolies—whether their own or those of the state. Big capital should exist but its owners should focus on developing and upgrading their businesses first and foremost.