“Are you satisfied with your life?” If you ask Ukrainians this question today, most of them will answer in the negative. At least that’s what opinion polls would have us believe. And if you dig a little deeper to find out why Ukrainians are not living better, a slew of factors will be named, some of which are very widespread. One of these is “the oligarchs.” Plenty of Ukrainians believe that they are the root of all evil in Ukraine. There are good reasons for this because the country’s tycoons have cultivated corruption, curtailed competition, preserved a technologically obsolete economy, established feudal rules of play, zombified voters through their media, and so on. Over the course of many years, they had considerable influence in Ukraine and used this not for the common good, to put it mildly. Ordinary Ukrainians are so fed up with their doings that the oligarchs are virtually the manifestation of evil on earth in the public consciousness.

This kind of perception has led to public demand for “de-oligarching,” something that was very evidently manifested during the Revolution of Dignity. At that time, many Ukrainians unambiguously understood and made clear that they wanted to see their country rid of its oligarchs. But no one had a clear plan for doing this. And so this desire would have remained frustrated if not for a series of events, whether accidental or deliberate, that brought Ukrainians closer to this goal. Sure enough, the oligarchs began to lose their influence.

Economic collapse

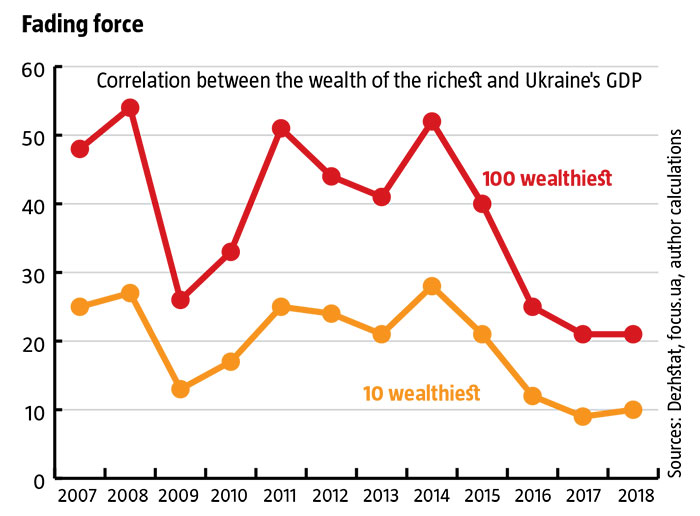

The extent of oligarchic influence in Ukraine can be measured in a variety of ways — and all assessments will be subjective as there are no clearly-defined quantitative indicators on which to base them. The only area where numbers are available is the wealth of the country’s tycoons, and these have shrunk considerably in the last few years.

Focus, a business weekly, writes that at the beginning of 2018, the 100 wealthiest people in Ukraine were worth US $26.9 billion. In late 2017, Novoye Vremia, another business weekly, assessed the assets of the country’s 100 richest people pretty much the same: US $26.7bn. Compared to indicators from the Yanukovych era, which ranged from US $62bn to US $80bn depending on the year and the valuation, today the country’s richest people have lost two thirds of their previous value. If their current worth is compared to what they had prior to the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 (US $101-113bn), then it is down to about a quarter. More importantly, where earlier the value of Ukraine’s richest people remained a steady 40-50% of GDP, today, they are barely 20% (see Fading Force). The same is true of the top 10 richest Ukrainians. Their worth in absolute terms and their share of GDP have shrunk radically. What’s more, this trend suggests that as the country’s economy recovers, their financial weight is not recovering along with it.

Given that the wealth of oligarchs generally determines their influence in a society, the government and various processes in the country, it can be assumed that the decline in their net worth is a good reason to feel optimistic. Certainly something is changing in Ukraine, the process of “de-oligarching” seems to be happening and their socio-economic weight is slowly fading. Could it be too soon to draw such conclusions? Is this change irreversible? How sustainable are the factors that have led to this decline?

War’s silver lining

“There’s nothing bad but some good comes of it.” This adage applies very well to the role of Russia’s war against Ukraine in the process of cutting oligarchs down to size. With the annexation of Crimea and the conflict in Donbas, the oligarchs — and the government and foreign investors, of course — lost a lot of assets. Some of these have been lost forever, because they were physically destroyed, and they can only be forgotten, regardless of how or when the war ends and Crimea returns to Ukraine. This cut down the economic clout of the oligarchs and that portion will never return.

More importantly, it’s hard to say that assets in Donbas or Crimea were especially attractive. Most of them were obsolete plants producing resources and were distinguished by neither efficiency nor profitability. Their main basis for earnings was a cheap labor force that was in turn based on the fact that most residents of Donbas never went beyond its boundaries during their lifetimes. This meant that there was always a surplus of workers that was artificially maintained through poor transport links, and weak socio-economic and cultural ties to the rest of the country. Its oligarchs were happy to keep things that way and certainly played a role in making sure they did. From the outside it looked strange: a supposedly wealthy region where most of the residents were unbelievable poor and backward.

RELATED ARTICLE: System recovered. Now back it up

The war changed everything. More than a million residents of the region were forced to migrate elsewhere, and by leaving discovered a different world. Transport links became much better, with regular buses going from Kramatorsk and Bakhmut to Warsaw, increasing the opportunities for people to leave the war-torn frontline area. Cultural and other ties grew stronger. The result is that the people of Donbas will never again allow themselves to be inevitably herded as cheap labor, that is, as a resource that allowed oligarchs to easily grow wealthier and gain economic clout. One indicator of this is reports of a shortage of labor in Mariupol. This forces the owners of plants in the area to increase wages and gain less of the kind of profit that once seemed to flow into their pockets without effort.

In some sense, the war in Donbas is like a disease that the doctors prescribed to a patient in order to get rid of other diseases. Despite all the horrors of this war, it became a major factor in cutting Ukraine’s oligarchs down to size. Sooner or later, the war will end, but the changes that it brought about will likely remain forever.

A fortunate migration

There’s a lot of talk in Ukraine about labor migration, which has become a national issue, about the millions of Ukrainians who have left for better jobs, especially to Poland. Yes, the problem is serious and could turn into a national security threat eventually. But in terms of “de-oligarching” Ukrainian society, this emigration has had a positive impact as it generates greater competition among domestic employers for those who have remained. Just as competition on the markets of goods and services tends to drive prices down and quality up, competition for labor tends to drive both salaries and productivity up. The more workers earn, the less goes into the pockets of the oligarchs, further reducing their economic influence.

Previously, the labor market was a buyer’s market, and so manufacturers and business owners were able to dictate the terms of employment. Oligarchs felt very secure in this kind of situation because they earned super profits thanks to cheap labor and put all their efforts into maintaining this state of affairs. Today, it’s a seller’s market, so workers get to set the rules. For oligarchs, this mainly means that the days of easy money are over. More importantly, this means that, to survive, they have to now focus on increasing efficiency — or die. With this kind of “law” coming into play, oligarchs will have to distract themselves from meddling in government processes, the rules of play, and so on, and concentrate on increasing the productivity of their businesses and re-investing serious money in their development if they want to stay afloat.

In such a situation, there will no longer be the resource basis for classic oligarchs to operate with. It’s easy enough to project that many of those in the top 100 will be unable to adapt to the new conditions and will either go broke or will sell their businesses and live on interest. Thus, labor migration has been a major factor in reducing the influence of the tycoon class and its effect will last for a long time to come.

The bankers’ move

Another important factor in the decline of the economic weight of Ukraine’s oligarchs was the purge of the banking system. It had two consequences. First, bank assets left the hands of many oligarchs, started with Vadym Novynskiy, Dmytro Firtash, Kostiantyn Zhevago, Oleh Bakhmatiuk and many others, all the way up to Ihor Kolomoyskiy and Ghennadiy Boholiubov when the government took over PrivatBank. This directly reduced their worth. Secondly, the model under which the banking sector operated was radically changed. Before, its main function was to pump money abroad, right into the offshore accounts of these same oligarchs — and not only theirs. From there, the money would pass through Cyprus, the Netherlands and the Virgin Islands or other popular “quiet harbors,” and return to Ukraine as foreign direct investment at the rate of several billion dollars a year.

Today, this money leaves the country in dramatically smaller volumes, as it is far harder to do so through domestic banks now. This means, of course, that more capital remains within the country and the oligarchs have to either work transparently, paying their proper taxes, which also hits their pockets like never before, or put considerably more effort to remain in the shadows. It’s much easier now to take them to court for any “grey” profits. And although the law enforcement system still leaves a lot to be desired in terms of operating effectively, the very threat is enough to demotivate would-be money-launderers and to force oligarchs to move away from the illegal methods of enrichment from the past.

Still, the key effect of cleaning out the banking system is not even this. The balance between the oligarchs and the state has changed completely. Under Leonid Kuchma, oligarchs were able to get things their way, buying officials. Under Viktor Yushchenko, the government was too distracted by in-fighting and other useless processes to get in the way of the oligarchs. Under Viktor Yanukovych, the oligarchs simply paid their fee for the right to do whatever they felt like doing, including usurping power. The shakedown of the banking system showed that the state, personified in this instance by the National Bank of Ukraine, could be a player and not just a resource in someone else’s game. The NBU set itself the goal of making things work so that everyone finally had to work according to transparent, fair and understandable rules.

And the NBU reached this goal, although it cost the banking sector dearly. More than likely, that’s the main reason there was so much noise made about Valentyna Hontareva: she made sure, not without considerable help, that the government started to establish the rules of the game for the first time. It was unprecedented and Ukraine’s oligarchs were clearly stunned by the boldness, as their nearly identical reaction to the purging of the banking system testified. Of course, there were some exceptions. For instance, in the four years since the Revolution of Dignity, the assets of the International Investment Bank, financed by Ihor Kononenko and Petro Poroshenko, grew 391%, nearly fivefold on paper — but 130% if the change in the hryvnia exchange rate is counted. This in contrast to the entire sector, which grew all of 1.6%. It’s possible that IIB is playing by the rules established by the NBU, but unlikely that it was without using oligarchic influence, given the pace of growth. Still, this exception confirms the rule. We’re talking about assets worth more than $350 million. Compared to what the oligarchs lost when they were given the choice to play by the rules or get lost—the difference is heaven and earth. And if this is placed alongside the tens of billions that the gangsters in the previous administration made off with, the current state of affairs looks almost ideal.

An empty trough

Oligarchs wouldn’t be oligarchs if they did not try to take advantage of their influence to bite off a bigger chunk of the public purse. In Ukraine, the public pie is very big, over 40% of GDP and for many years it was subject to constant encroachments by fat cats. Under Yanukovych, the flow of public money into their pockets turned into a torrent.

Today, things have changed, in many ways thanks to the introduction of the ProZorro electronic procurements system. Some skeptics maintain that public money was being stolen, is being stolen and will continue to be stolen. To persuade them otherwise, articles like this aren’t enough, but it’s still worth taking a more comprehensive look at the situation. In the last two years of the Yanukovych administration, Ukraine’s GDP in dollar terms was 50% larger than what is projected for 2018. The expenditure side of the budget was also about that much larger, counted in hard currency. Yet on today’s much smaller sum Ukraine is rebuilding roads, rebuilding a professional army, making world-class movies, carrying out extremely expensive, large-scale reforms, reviving the regions through decentralization, and doing much more that once could only have been dreamt of.

Does this not indicate that oligarchs are getting a far smaller chunk of the state than before? Of course. If they are still stealing, it’s on a completely different scale. And this means that the budget is no longer the shaping factor of economic clout for the country’s tycoons.

Outside influence

There’s also the assistance Ukraine is getting from its western partners and international financial institutions (IFIs). Here the financial aspect is not the only one, and is accompanied by technical, diplomatic and other activity. There’s ample evidence that the properly calibrated and directed pressure of the IMF, US and EU was a key factor that assured the nationalization of PrivatBank would go through. And even if it had happened anyway, what chances would there be that Kolomoyskiy would return the billions that he siphoned out of his company? Since the High Court in London seized Privat Group assets worth US $2.5bn, the chances are very high, indeed. Ukraine alone could never have achieved that.

Without western assistance, Firtash would not be sitting in jail and would not be taken out of the geopolitical game as a very powerful fifth-column agent of Russia’s in Ukraine. Without pressure from the US and EC, Mykola Martynenko would not be behind bars today, and Oleksandr Onyshchenko would not have fled abroad but would probably still be leeching off Ukraine. All this was because “that SOB” Serhiy Shokin remained as Prosecutor General and sabotaged any attempts to serve justice. Without western assistance, an entire series of anti-corruption agencies might never have been formed. They might not be producing results as well as wished, but they have already shifted the balance of power and have considerably improved the odds that someday thieves really will go to prison in Ukraine.

Unfortunately, public discourse today keeps focusing on the question of what right the IMF has to set conditions while politicians keep making hay over the relatively minor—compared to the task of rebuilding a viable state — issue of household gas rates. Why do they not admit that the West has done something huge for Ukraine, something Ukrainians would never have achieved on their own. If we look at the big picture, the direct and indirect impact of the steps our western partners have taken, it’s possibly the single most important factor in cutting the economic clout of the country’s thieves-in-law, i.e., oligarchs, down to size. Even the impact of the war was not as large-scale and systematic as the actions of the West. The only conclusion that can be drawn is Ukrainians have been given a chance to become normal, to build a humane country that is focused on its citizens and has excellent potential for growth. But no, many Ukrainians seem determined to turn up their noses and focus on trivialities. Considering the prospects for future generations today, this is a crying shame.

Here, the difference between the West and Russia is particularly obvious. Russia not only cooperated with Ukraine’s oligarchs — it actually nurtured them, trained them and fed them with petrodollars. In short, Moscow did everything possible to keep this obsolete, degenerate neo-feudal system in place, where a clowder of fat cats stood against a nation of beggars. It’s as though the Kremlin suffers from a chronic need to surround itself with a belt of surrealism: territories with unrecognized republics, frozen and not-so-frozen conflicts, military bases, befogged residents who are busy struggling to survive while all kinds of degenerates run the show. It’s as though these territories are intended to serve as a distorted mirror for Russians, that doesn’t reflect their own flaws at all.

The West, by contrast, aims at stimulating development in partner countries. Without much ado, it strikes at the roots of the oligarchies and other sources of stagnation. In this way gives the country a chance to reach the maximum heights, which can be seen in Poland’s success. The result in the last few years has been that the economic influence of Ukraine’s oligarchs has inexorably gone down as they lost assets, shadowy sources, and profits based on legal loopholes. The result, as well as a secondary indicator, has been a drastic decline in the quality of the country’s team sports. All of them, but especially football, have long been completely in the hands of oligarchs. They owned the clubs and had enormous influence over the national federation. Everything was blow out of proportion and out of touch with reality: clubs boasted of multi-million dollar budgets, of buying expensive players, of paying Ukrainian players sky-high salaries that did not always reflect their actual skills on the field. In fact, enormous sums of money were being laundered through sports. No longer. Over the last few years, a number of high-profile clubs have simply disappeared for lack of financing — nor has this process stopped. Those that have survived are now paying players less, selling their top guns, have no way to invite new, expensive players, and are forced to give up truly talented Ukrainians to play abroad. This situation, of course, reflects the reality on the ground in Ukraine far more accurately.

Releasing large-scale potential

Yet another consequence of the decline in oligarchic power in the socio-political realm has been the release of mass energy, especially entrepreneurial. The pressure of oligarchs on the state, both direct and indirect through regulatory and enforcement means, made it hard for people to develop themselves, to engage in business, and to use their heads to make money. Things were especially depressing under Yanukovych. Now the pressure has gone way down. So if we look at GDP growth over 2014-2018, positive growth can be seen in the least oligarchic sectors: hotels and restaurants, information and telecoms, administrative and support services, real estate. The core oligarchic industries in extraction, processing, power generation, gas supply and so on have declined by the double digits.

RELATED ARTICLE: The cost of a good wage

Ukrainians have gained a measure of freedom and have taken the initiative into their own hands. This has led to radical changes in the shape of Ukraine’s economy. Yes, pressure on businesses remains very high and is a serious barrier to growth. Obvious examples are plenty: the games being played at Nova Poshta or at IT companies, massive corporate raiding in the farm sector, and so on. But all of this is already fragmented: it is no longer concentrated in the hands of oligarchs or thieving government officials but is evidence of the leftover oligarchic-official structures that continue to hold on to some power, refuse to recognize change, and continue to do “business as usual.” Their pressure is no longer systemic. It’s far easier to avoid it today than it was five years ago. But to eliminate it once and for all, the system itself needs to be changed: weakening the oligarchs is not enough.

The oligarchs are economically broken, but this is only the first step towards getting rid of their system. The point of no return has not yet been reached. All it would take is for high-profile, unsinkable “friends of oligarchs” to come to power, plenty of whom have declared themselves in the 2019 elections and some of whom have some of the top ratings today, and the situation will be undone, with new Kononenkos, Ivanenkos and their ilk crawling out of the woodwork. To enshrine today’s success in the confrontation with the oligarchy, the practice of the NBU needs to be scaled up and institutionalized, that is, everything must be done so that the maximum number of government agencies — and eventually the entire government at all levels — will be capable of establishing a level playing field for all and ensure that they are adhered to equally, across the board. This means having a professional, well-paid civil service with a suitable worldview, police and judges who are not on the take, government agencies prepared to work for the people and not the paper. In short, much more remains to be changed and millions of effective, directed person-hours need to be spent doing it.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook