“May you live on a single salary!” This quote from a popular film by Soviet comedy director Leonid Gaidai was a half-humorous curse back then. Wages were very low for most people and those who didn’t make any money under the table had little to cheer about. Much water has flowed under the bridge since that time, but during the crisis years of 2014 and 2015, most Ukrainians found it a serious challenge to survive just on their regular wages. In the few years have passed since then, Ukraine is rapidly moving towards a record level of wages since it became independent.

The wage roller coaster

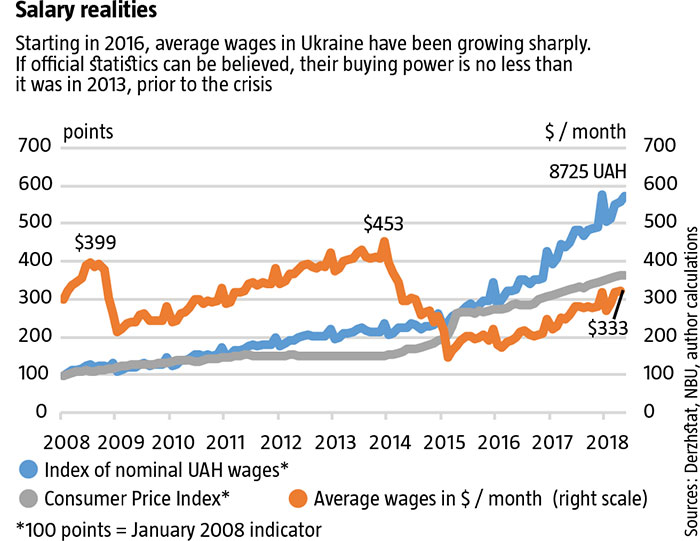

According to Derzhstat, the government statistics agency, the average official monthly salary in Ukraine reached UAH 8,725 (see Salary Realities). In Kyiv, it passed UAH 10,000 in 2017 and today it’s over UAH 12,000. Is this a lot or a little? Compared to indicators in Europe, even Eastern Europe, these numbers are no match. But if they are compared to certain domestic markers in Ukraine, the situation looks a lot better. Calculated in hard currency, the average Ukrainian worker made $333 in May. Prior to the great recession of 2008-2009, when the hryvnia fell from UAH 5/USD to UAH 8, the maximum this indicator had ever reached was $399. In 2013, just before to the crisis of 2014-2015, it was up to $453, which was substantially higher that what it is today. But if wages continue to rise at their current pace, in another 12-18 months they should break the record for independent Ukraine.

From time to time, it’s possible to hear fans of the “stability” of the Yanukovych era, who are still abundant, tout their favorite line: “Bring back UAH 8 to the dollar so that it stays that way for many years and we’ll be happy.” But they don’t say anything about how unrealistically high today’s wages are at the old exchange rate. In hard currency terms, they are not that different from what was paid during the period of “stability.” This is phenomenal given the depth of the crisis that the country struggled through over 2014-2015. But the main thing is that today’s level poses no real threat to macroeconomic equilibrium, unlike back then, because it’s not based on artificial, deliberate support at the cost of the competitive edge of domestic manufacturers, declining exports and an enormous hole in the balance of payments. With the current wages, both the employer and the employee have room to grow. This alone would be plenty of reason for optimism.

The other indicator is price levels. According to Derzhstat, the Consumer Price Index has risen almost 139% since the beginning of 2014. But nominal wages have risen 167%, which is a bigger increase than prices. This means that the average Ukrainian worker can afford at least as many goods and services as during the “stable” Yanukovych years. In short, there’s no basis for saying that Ukrainians lived better then.

Some will argue that prices actually went up considerably more since the start of the crisis. But the official indicator includes the widest possible range of goods and service that are available in Ukraine, meaning those products whose prices have tripled, together with the dollar exchange rate, and those whose price has hardly changed at all. For comparison, a number of other price indices can be considered. Many Ukrainians orient themselves on the cost of food or utilities. So, food prices have gone up 123% over this period, while residential services such as water, power, gas and other fuels, have skyrocketed 350%. So, if wages are compared to food prices, Ukrainians now earn more bread than they did prior to the crisis. But people for whom residential services take the lion’s share of their wages have good reason to feel that they are poorer than they were under Yanukovych. Yet they are the ones for whom the state subsidy system was set up in the first place. So there’s a big question whether those whose utility bills are largely covered by the government have really become any poorer.

RELATED ARTICLE: The five whales

Reducing payroll contributions

The dynamic of wages in Ukraine in the last few years is indeed curious and noteworthy. Under certain circumstances, employers are not terribly inclined to even index their employees’ wages to inflation. Yet the wage growth has been outpacing inflation. A number of causes have contributed to this.

Chronologically, the first factor was a reduction in the consolidated social contribution (CSC) from 22% starting in 2016. After this change, many politicians complained that employers were not directing all the savings that resulted to their employees’ wages, meaning that it did not turn out as expected. However, it was after this that wages in Ukraine began to grow at the high pace that we can see today. A number of polls taken among employers testified that a significant part of the savings on the reduce CSC did go to employees, although not 100%, obviously.

Even if employees did not get the entire difference, there was a positive aspect to it. Starting in QII 2016, three months after this cut in the contribution, investments in Ukraine suddenly bounced up. As a result, the gross accumulation of fixed capital has been growing every quarter since then, with real growth ranging between 15% and 25%. This very positive trend demonstrates that new, more effective jobs are being generated that will ensure higher wages in the related sector down the line.

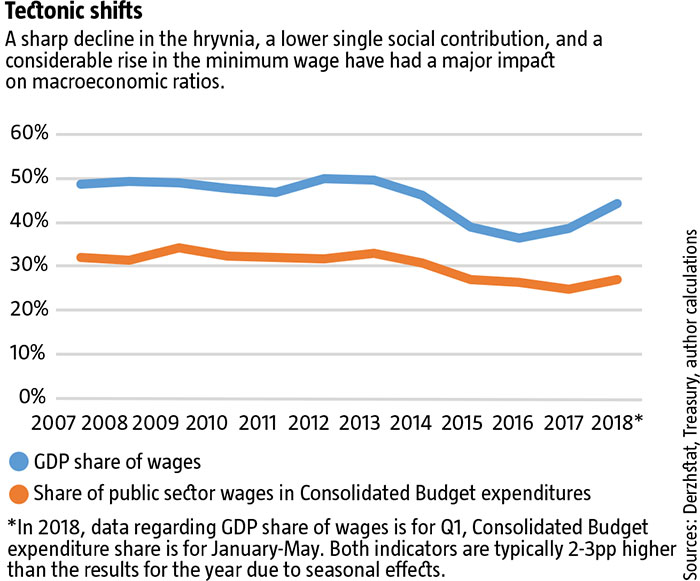

In fact, this has been evident from certain macroeconomic ratios (see Tectonic Shifts). In 2013, prior to the crisis, payroll costs, meaning wages plus contributions, added up to nearly 50% of GDP and were 33% higher than gross profits and mixed incomes. In other words, employers were spending more on payroll than they were leaving themselves as profit. But this meant they lacked development capital, which led to economic stagnation in the last years of the Yanukovych administration. When the crisis began, wage levels stayed almost the same for some time, but profits began to increase, because the income share was tied to hard currency for employers. Reducing the CSC share spurred this trend so that in 2016 the payroll share of GDP was already down to 37%. In short, companies were giving their workers a smaller share of the added value generated, but many of them ended up spending the additional capital on developing the business and increasing efficiency. This provided the conditions for wages to grow down the line, as we can see today.

Raising the minimum salary

There were, unfortunately, also employers who spent the savings from the reduced CSC neither as intended, that is, to increase net wages, nor to grow their businesses. Seeing this, the Government decided on a second step in 2017: it doubled the minimum monthly salary (MMS), which has gone up noticeably in 2018 as well. This affected the average wage substantially, not only and not just as much because corporate wage scales were tied to the MMS, but because in depressed and grey areas of the economy, workers were generally getting just the minimum salary officially, with the rest in cash under the table in businesses operating in the shadow economy—or nothing in the case of depressed sectors. In short, raising the minimum monthly salary significantly changed the weight of the payroll fund in these sectors.

This impact has also appeared in official statistics: of the 12 sectors of the domestic economy where wages were rising at a higher-than-average pace over 2014-2017, 7 sectors, including farming, construction and retail trade, were below-average in 2013. In other words, low wages in those sectors were caused by the fact that the majority of employees were being paid the MMS, so as soon as it began to go up, wage growth was driven up much faster than in other sectors of the economy.

Raising the MMS had a positive impact on macroeconomic rations as well: the GDP share of payroll began to go up in 2017, almost immediately after the MMS went up. Of course, this move had negative consequences as well, as it significantly increased the GDP share of shadow and depressed sectors, which led, for instance, to a noticeable increase in the consumer cost of foodstuff and increased mark-ups in the retail sector. But the positive impact so far seems to have outweighed the negative side effects quite thoroughly.

RELATED ARTICLE: Not bad, but could be better

Market factors

In addition to these two structural ones, there are a number of market factors that are also driving up wages in Ukraine. First of all, there’s competition for Ukrainian workers abroad, especially in Poland. Earlier, a Ukrainian who wanted to go abroad to work had to expend considerable effort and take on substantial risks: get a visa, typically a tourist one; arrange transportation, which was not always easy or accessible; find an illegal job; and hide from foreign law enforcement agencies the entire time to avoid deportation. The situation has changed radically. Job opportunities abroad are posted on just about every lamppost: assembly plants in Poland offer official employment with salaries in the UAH 20,000 per month range in local currency. Among all the annoying, endlessly flashing ads on the internet, there was recently one calling for rebar workers to build the subway in Warsaw. Leaving Ukraine is easy: buses to Poland leave just about every oblast center several times a week. Today, buses go to neighboring EU countries from Kramatorsk and other cities near the war zone in eastern Ukraine. This means that there are people there who want to go, whereas, not that long ago, the number of locals who went to Europe for work could be counted on the fingers of one hand. In short, the infrastructure for “exporting” Ukrainian labor has developed enormously in the last few years. So, if local manufacturers want to hire decent local workers, they now have to compete with companies in Poland, Czechia and elsewhere. This means raising wages and doing everything to keep increasing them and remain competitive on the domestic labor market.

Secondly, wage levels in a slew of sectors is closely linked to the hryvnia exchange rate. For instance, of programmers are not paid a decent dollar or euro salary, they will easily find work outsourcing for some foreign company that will pay them in foreign currency. This pushes wages up in certain sectors in relation to the dollar or euro exchange rate. That also explains why the average salary in the information and communications technology (ICT) sector rose 161% over 2014-2017. If IT companies are separated out, the level of salaries in that sector probably rose 200-300% and more. In aviation, salaries tripled, reflecting both the global nature of the sector and the hard currency dimension of salaries, as well as the strong growth of air transport in Ukraine over the last few years.

Thirdly, there are sectors that have had a significant boost thanks to changes that have taken place in the country since the Euromaidan. For instance, light industry, where the key factor is low labor costs, has been growing by leaps and bounds. This has been driving demand for workers, which is evident from the large number of advertisements looking for professional stitchers. Over 2014-2017, the average wage in the industry grew 190%, noticeably higher than the industry average and the overall economy. Meanwhile, budget expenditures on salaries for military personnel increased 207% during this period, and another 23% over January-May 2018. The reasons there are obvious to all.

Consequences and conclusions

So, the rise in salaries observed over the last three years has been driven both by Government policy, such as reducing the CSC and increasing the MMS, and by market factors. In both cases, the result has been positive: wages are going up and the standard of living of ordinary Ukrainians is getting better. Over 2014-2015, there was a visible decline in the number of shoppers and a phenomenal number of pensioners begging in the streets, something that had not been evident during the global crisis of 2008-2009. Today, shopping chains are filled with traffic and there are visibly fewer beggars.

All this would be wonderful if not for one “but.” The thing is, that the normal salary range is determined by the structure and technological level of a country’s economy. The crises of 2008-2009 and 2014-2015 that the technological ceiling for averages for Ukraine is around $400-450: anything that’s higher tends to not last long and is eventually adjusted when the hryvnia is devalued and another crisis looms. This means that Ukraine is already approaching its wage ceiling.

To raise that ceiling significantly, years, if not decades, of macroeconomic stability and regular investment are needed, and, of course, attractive conditions for investors. And this is where problems tend to arise: the country has a huge foreign debt burden that needs to be serviced and paid off, and if cooperation with the IMF is not restored, the country could face yet another crisis in 2018-2019. If that starts, Ukraine will once again be unable to raise its technological ceiling substantially and Ukrainians will once again find their standard of living in collapse as the hryvnia depreciates. How well can the country survive yet another economic decline and what will it look like when it emerges again? This is the question the government today needs to concern itself with most of all.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook