In the fall of 1929, a huge rally gathered in the Kharkiv Central Club of Proletarian Students. Over 700 students were protesting against the “hooliganism” and “pornographic” performances of Valerian Polishchuk and were prepared to fight decisively against this advance of the class enemy in literature.

An official from the propaganda department of the district Party committee warned about the rabid opposition that class enemies were launching on the ideological front. Speakers from the student bodies of Kharkiv post-secondary institutions—institutes of people’s education, people’s husbandry, technology, medicine and veterinary medicine—demanded that the activities of “polishchuks” be stopped. As one worker by the name of Volodchenko from the electro-mechanical factory declared that they did not need writers like Polishchuk.

How did the class enemy manage to show up in Ukrainian soviet literature? Hundreds of students were corralled into a demonstration against the magazine Avant-garde #3, in which Polishchuk addressed readers as the mouthpiece of class enemy forces on behalf of some mysterious “enemy.” Against a journal of a mere 110 pages with the cover, worth 1 karbovanets and 20 kopiykas. And against the eponymous literary group that consisted of some 20 people.

The rally of proletarian students passed a resolution declaring a fight to the death with polishchukism, hooliganism, pornography and counterrevolutionary elements in literature, called for the further literary activity of Avant-garde to be stopped, to investigate who allowed such a pathetic journal to be published, and to demand from the literary union that it immediately fight against the class enemy.

Avant-garde #3 (1929), cover by Vasyl Yermilov

The right to be

Back at the beginning of that year, Avant-garde still enjoyed the support of Education Commissar Mykola Skrypnyk. On February 21, 1929, Skrypnyk suddenly mentioned this small but colorful group in a famous speech on the pathways for Ukrainian literature to develop during a public debate at the Vasyl Blakytniy Literary Building in Kharkiv.

“There’s one small literary group that is earning its right to be,” the Commissar began distantly. “This is Avant-garde. Many, many want to deny this group’s existence altogether, saying that there’s no such group. But my respected Comrades, this is what was done with the Ukrainian people: many denied that they even existed, but we do exist, after all.” The room laughed.

But Skrypnyk had not come to joke. “Let’s hear a little less laughter about an artistic symbol, and more esthetic art criticism of it,” he challenged. “This slogan, to my mind, should be the slogan of our daily artistic life.”

The conceptual inspiration, organization and management of Avant-garde came from Valerian Polishchuk, who never worried and never lost hope. At the end of 1925, he left the authoritative Hart Union of Proletarian Writers, which was falling apart before people’s eyes. Just before Polishchuk left, a huge group of writers had quit and immediately formed the Free Academy of Proletarian Literature. But with its conservative academicism and focus on classic models, VAPLITE did not suit him. He decided to form a separate organization that would promote and defend new, constructive art.

RELATED ARTICLE: Love, pride and class prejudice: The authors, readers and anti-bourgeois persecutors of romance novels in the 1920s

In 1926, a pamphlet called The Backward-Looking Hart came out, with a challenge from the Avant-garde group of artists. In an open letter to Hart’s executive committee, Polishchuk explained in great detail why he had left the Union of Proletarian Writers—mostly because it was bureaucratized and encouraged creative stagnation. “Hart has constantly promoted and supported the deliberate hackery of so-called ‘agitliterature,’ built on old forms and aimed at outdated tastes, with absolutely no creative spark.”

This was followed by a challenge from the artists of the new group Avant-garde, who declared themselves against all that was outmoded, bourgeois, “enlightening” and isolationist in favor of breaking canons, the poetry of industrialism, expanding language diversity, precise formulations in poetry, and the rhythm of telegrams, aerograms and proclamations.

“We are raising the battle cry for true contemporary Europeanism in artistic technique, by exposing and eliminating the epigonism based on long past and now outmoded artistic and literary forms,” Valerian Polishchuk announced, together with four Kharkiv artists. Ahead of them was a hard fight, not only with the outmoded and conservatism, but for the very right to exist.

A private initiative

The Avantgardists were wasting their time appealing to the Party and the public: “We appeal to the Communist Party and all of soviet society to meet us halfway in our creative first sheafing, to reinforce us both morally and materially, because this is in the interests of our common culture. So first all, we call on our new society to respond to us in your sensitive minority with an encouraging voice.”

Avant-garde had to wait three long years for state support and in the 1920s, that was an eternity. For instance, VAPLITE confirmed its statutes with the Communist Party Central Committee in Ukraine and a month later, it was allocated premises, 5,000 karbovantsi for its club and 50,000 kbv for its monthly journal. The secret might have been that among the vaplites were 10 Party members, whereas not one communist from the Party executive was in Avant-garde.

Avant-garde members listen to the radio: Left to right: Filliped, Yermilov, Patoka, Pankiv, Troyanker, Polishchuk, Chernov, and Berman, Kharkiv, 1929

And so, Avant-garde began and continued to develop as a private initiative. The proclamations of the Avant-garde arts group were signed by Polishchuk and his fellow artists, Vasyl Yermilov, Georgiy Tsapok and Oleksandr Levada. At the bottom was the mailing address: Kharkiv, vul. Vilnoi Akademiyi 6-8, Artem Social Museum, Artists’ studios. Or Kharkiv, Pushkinskiy vyizd 6, Apt. 9, V. Polishchuk. The quartet of Avantgardists printed up a book at their own expense. That same year, Polishchuk’s work, The Literary Avant-garde, came out, also self-published. The next book, The Pulse of an Epoch, with the subtitle “Constructive dynamism or militant regression?” came out in 1927 as published by the State Publishing House of Ukraine. Interesting that the print run for both was the same: 3,000.

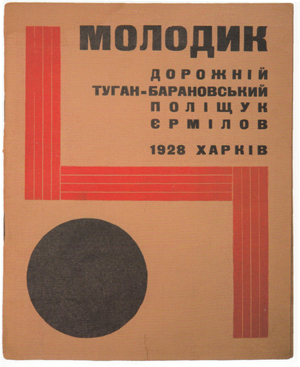

Polishchuk’s books of poetry kept being published one after another as though there was nothing to it. But not everyone was so lucky, because not everyone managed to gain a reputation as the Homer of the Revolution by the mid-1920s, as one respected literary critic referred to him. Two younger fans of Avant-garde, Ivan Dorozhniy and Mykailo Tuhan-Baranovskiy Jr., had to put their first joint collection, Molodyk or “New Moon,” out on their own, and the cover they printed something unusual: “Recommended by Val. Polishchuk.” “Two of my literary and artistic friends brought their works and begged me to provide the foreword,” the recommender explained, “because if you’re going to self-publish today, it’s better if someone promises to defend a particular work of art from our disputatious, politicized and predatory literary population.”

In 1928, the Russian section of the group also self-published a collection of poems, which they called A Radius of Avantgardists.

The Avant-garde jazz band

Only in October 1928, after a three-year “aging process,” was Avant-garde given some money to publish a periodical. And for this they owed thanks to their powerful mentor, Education Commissar Skrypnyk.

After the first proclamation in 1925, much time went by until October 4, 1927, when a group of artists gathered in the Academics’ House and approved the Avant-garde resolution:

“We want to jointly engage in artistic explorations, inventions and creations, so as not to be stuck at the level of contemporary petty little standards of artistic creativity. To present an independent, avant-garde artistic word, sound, color and construction, we need to put together a series of collections and a gazette journal. We appeal to Ukrainian soviet society, the Communist Party, and the government to assist us in this our endeavor.”

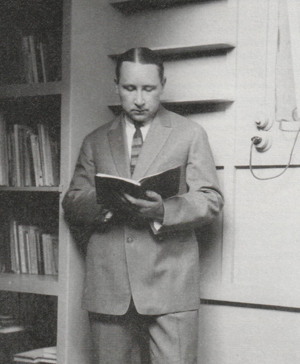

Rayisa Troyanker, late 1920s Mykhailo Pankiv, early 1930s

It was not the first time the artists had made this kind of plea and this time there were 15 signatures on the resolution: one artist, two musicians and 12 writers. In time, Polishchuk admitted that they “ended up having to print materials out of pocket and to engage people who were not quite ready for this kind of work.”

At this point the Avantgardists decided to take the bull by the horns: two months later, in winter 1928, they went with their platform to Skrypnyk’s office at the People’s Commissariat of Education. And he went and invited them in his introductory speech at a literary debate. The Avantgardists responded in writing that the presidium of the Vasyl Blakytniy House of Literature had not suggested that they take part in the debate, but had organized the event exclusively for members of the House and invited guests. Above all, the Avantgardists were simply not members of this organization.

Both the meeting and the letter had their consequences. Polishchuk and his Avantgardists did manage to go to the debate and Skrypnyk both mentioned and supported them in his speech. The March Bulletin of the People’s Commissar for Education published a resolution by Skrypnyk about the declaration and appeal of the Avant-garde group: “to agree to possible assistance from the PCE to the literary workers of this group” and “to turn to the State Publishing House of Ukraine with a proposition to discuss the possible forms such assistance might take.”

RELATED ARTICLE: The history of Kharkiv: from Cossacks to bolsheviks, Famine and WWII

In October, the Avant-garde Bulletin came out, containing a detailed proclamation from the literary group. But now there were fewer signatures under it, but those that were, were reliable individuals: Valerian Polishchuk, Vasyl Yermilov, Leonid Chernov, Rayisa Troyanker, Viktor Yaryna, Valentyn Borysov, and Oleksandr Levada. Yaryna’s name was in a black border: the writer had been sick with tuberculosis and did not live to see the first issue of the Avant-garde journal.

Subsequent issues had a different name, but the numbering of the pages was continuous. By the time the issue called “Artistic Materials of the Avant-garde” came out in 1929, the editorial list had significantly expanded. Ukrainians like Mykhailo Pankiv and Oleksandr Soroka appeared, Germans like Johannes Becher and Kurt Kleber, Russian constructivists Illya Selvinskiy and Korniley Zelinskiy, myth-maker Edvard Strikha, architects Ivan Nemolovakiy and Bruno Taut, composers Kost Bohuslavskiy and Yuliy Meitus, photographers Serhiy Kryha and Andriy Paniv, artist Oleksandr Dovhal, and designer-typesetter Yakiv Rudenskiy.

The journal wrote about literature and painting—and even about music. An article by Polishchuk appeared in the Bulletin entitled “In favor of jazz bands and foxtrots,” while in the last issue, the score of a Jazz Etude by Meitus was published. In soviet terms, this was already irreverence that bordered on hooliganism[1].

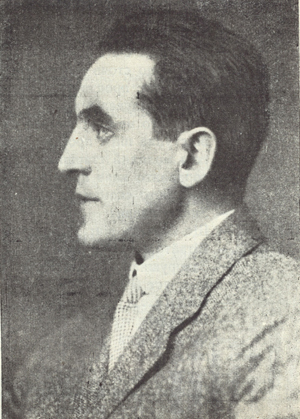

Vasyl Yermilov in Kharkiv, 1928–1929 Leonid Chernov, 1927

As before, the journal survived on sheer enthusiasm. “Avant-garde works without literary fees to authors,” Polishchuk admitted at one point. “Those who contribute to our literary publications have no material benefit from it whatsoever, other than additional costs and possible attacks on them by regressive elements. But they have moral satisfaction engaging in this cultural project.”

The literary pricelist

The section on red writing in the journal was called “Literary pricelist.” Some of the authors mentioned in the list of members never managed to get themselves published in the short-lived Avant-garde journal, but others were associated primarily with this publication and the group. Today, as then, people mostly knew of Valerian Polishchuk and Vasyl Yermilov. The painter Oleksandr Levada is persistently mixed up with a similarly named playwright in reference books and encyclopedias. Some of these individuals cannot even be found in Google, although the Avantgardists were unusually interesting people with adventuresome biographies.

The real surname of Leonid Chernov was Maloshiychenko, a native of Oleksandria, Kirovohrad Oblast. He studied and worked in the Surma Theater Troupe in the Franko Theater. He also organized his own theater, Makhudram, as a studio for artistic drama. Eventually he and his friends organized a mobile theater in Kremenchuk called Verda Stelo, meaning Green Star in Esperanto. Their ultimate goal was to translate the entire revolutionary repertoire into Esperanto and go on a world tour. But the nearby Kremenchuk workers wanted Russian soaps instead. To rescue the project, Chernov wrote and directed a detective play called “Sherlock Homes” and played the lead himself.

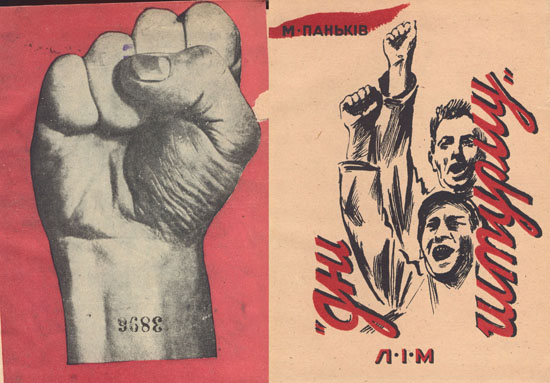

Mykhailo Pankiv, Stormy Days (1934), cover by Vasyl Yermilov

Verda Stelo died in a battle with famine, while Chernov wandered off all the way to Vladivostok. There, he worked in the press and even in the Chinese consulate, organizing literary evenings, scandalizing the bourgeoisie, imitating the imaginists—a Russian offshoot of English imagists—, writing poetry and prose in Russian, and publishing a collection of poetry called “An Association of the Insane” in 1924.

His American girlfriend kept urging him to come to San Francisco, but instead Chernov sailed off to India on the Transbalt in 1924. The route went from Vladivostok to Odesa and led to the book “125 Days in the Tropics.” From Odesa, Chernov traveled to Leningrad, where his fiancée was waiting for him. While in India, however, he had caught pneumonia and living in the northern marshes brought on a serious case of tuberculosis. His friend kept urging him to move to Kyiv. At that point, Chernov broke with the Russian imaginists, got on his motorbike, and returned home to Oleksandria. Starting in March 1927, he wrote only in Ukrainian.

Chernov began to publish actively and joined Avant-garde, and his stories began to be published. He also organized radio broadcasts in Ukrainian, and produced the first radio briefs and radio plays. He rode his motorbike and kept campaigning for Avtodor, the highways department. He wanted to name his fullest collection of poetry “Kobzar on a motorcycle,” but it came out posthumously under the name “At the Corner of Storms” instead, in 1933. At the writer’s graveside, Maksym Rylskiy said, “Chernov is dead, long live the Chernovs!”

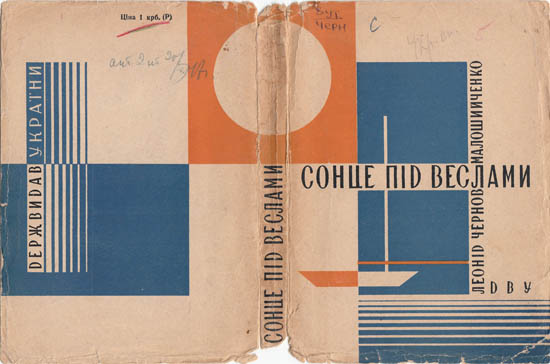

Leonid Chernov-Maloshiychenko, Sun under the Oars (1929), cover by Adolf Strakhov

Rayisa Troyanker was born to a poor family of Uman Jews and dreamed of getting away from the stetl from an early age. At 15, she fell in love with a tiger tamer and ran away with a traveling circus. Every evening, Raya would put her head into the tiger’s jaws and dedicated the poems published in Avant-garde to her fine-striped friends. Eventually, she married an Uman writer by the name of Onopriy Turhan and began to go to the local studio of the Pluh or Plow Union of Rural Writers. Rumors have it that the young family moved to Kharkiv, not because of the husband’s career but because his young wife’s passion for the handsome Volodymyr Sosiura, who had come to Uman on a literary tour.

Rai-ya, meaning “Paradise is me,” was the way she preferred to write her name. She gained fame among writers for loving many and among readers for writing erotic verse. In her first book, had been gifted to the literary critic Ivan Kapustianskiy, a number of handwritten comments from the observant reader can be seen next to her love poems: Sosiura? Polishchuk? The Russian dissident Lev Kopelev once recalled: “All of us, yesterday’s school kids, undoubtedly were captivated by the Avant-garde poetess Rayisa T. Small, slender, very heavily made up, she read poems in which she told about the first time she surrendered.” At bachelor evenings, the most popular poems were the “off-the-cuff” verses of Troyanker and Sosiura.

When Avant-garde collapsed, Rai-ya married the Russian poet Illya Sadofiev and moved to Leningrad.

Journalist Mykhailo Pankiv was from Zakarpattia, from Sighetu Marmatiei. He began to be politically active early and was already a member of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers’ Party in 1909. During the liberation struggle, he went over to the Borotbists or “fighters”, a Ukrainian petty-bourgeois leftist-nationalist party, and edited the central party newspapers. When the Borotbists joined the Communists, the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party sent him to work in Lviv to shore up the Communist Party of Western Ukraine. There, he was arrested and sentenced to hard labor at the secretive Sviatoyursk process, where 39 Ukrainian and Polish communists were tried on October 30, 1921.

Pankiv was able to escape from prison. In time, the soviet government sent him west again, but this time as a member of the publishing business: he organized two expositions of soviet books in Prague and Vienna, and negotiated with Vinnychenko the publication of Soniachna Mashyna or The Solar Car. And it was thanks to his initiative that the State Publishing House of Ukraine finally bought the rights to publish the novel in the Ukrainian SSR. When he came back, Pankiv worked as the deputy director of the Radio and Telegraph Agency of Ukraine (RATAU), a news agency, at the Education Commissariat. There, he wrote reports, novels and screenplays. His novel Judge Reitan, about a two-faced judge and the flight of a Romanian underground revolutionary from Sighetu torture chambers was brought to the screen in 1929 and became a very successful movie across the Soviet Union.

Ivan Dorozhniy and Mykhailo Tuhan-Baranovskiy Jr, Molodyk, (1927), cover by Vasyl Yermilov

Mykhailo Tuhan-Baranovskiy also led the secret life of an agent. He was the son of a well-known economist and Minister of Finance of the Ukrainian National Republic (UNR). Finding himself an émigré, the younger Tuhan-Baranovskiy became a social revolutionary and a maximalist, carrying out combat missions to liquidate White Guard émigrés for his organization. For these actions, he was sentenced to death in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. In the late 1920s, he himself gladly told the adventuresome tale of his life to young fans of Avant-garde in Kharkiv. After that two books of Tuhan-Baranovskiy’s were published: a collection of poetry joint with Ivan Dorozhniy called Molodyk in 1927, and the prose work, “Tales without Names” in 1928. Nearly all his later works were about the lives of Ukrainians and Russians in exile in Czechia and France.

The heroic revolutionary disappeared from Kharkiv as suddenly as he had arrived. Some said he was arrested as a spy, others were certain that he was called to Moscow and sent abroad once again. Before WWII, people saw him in Moscow, alive and well. During the Second World War, Tuhan-Baranovskiy worked in soviet counterespionage for SMERSH. He lived out his days quietly in Saratov and was published under the pseudonym Svitiazkiy.

Lenin, porn and betrayal

The third issue of Avant-garde ended up being the last one. It’s leader, Valerian Polishchuk, made the mistake of attacking something sacred—Lenin and the phony prudery of soviet society. Avant-garde #3 included an article entitled “Long live the public kiss on a naked breast!” and a series of Polishchuk’s aphorisms under the title Kaleidoscope. Among them was a very seditious opinion: “I have been convinced for the umpteenth time that the class struggle is not the foundation of human nature, that class struggle is merely a forced human need when you accept that humanity is simply a particular species of highly-organized animal, but nevertheless an animal. What can you say about class struggle,” Polishchuk asked,” when even a cat and a dog can live together peacefully?” As factory workers said at one public rally, with Polishchuk, Lenin became a nonentity.”

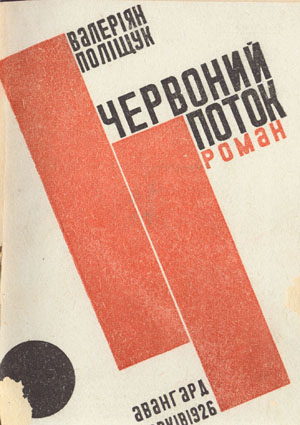

Valerian Polishchuk, Red Stream (1926), cover by Vasyl Yermilov

Worse was yet to come. Polishchuk called on the soviets to take an example from the Japanese and not be prudish about the healthy and beautiful functions of the human body. Not invent ugly, taboo topics. He started with himself and the Avantgardists by talking about their own lives. The spiciest details came with Yermilov: “Given the lack of comfort in divans made by the Central Workers’ Cooperative for coupling, Vasyl Yermilov is now making inexpensive, convenient and beautiful bench-bed to engage in these life-giving human functions. To assist our artist in his work, his wife is there to offer advice. And so we announce a new slogan: For cleanliness and openness, for healthy bodily functions, even in public. Long live the public, juicy kiss on a naked female breast.”

The campaign to harass Polishchuk was organized quite quickly. In fact, he had been a pain in the neck from the very start, with his accusations of conservatism and outdatedness. As one commentator maliciously put it, “it seems that the only thing that’s been organized is a jazz band, the foxtrot, and the Avant-garde Bulletin.” Now the government paper, Central Committee News, published a letter from literary organizations that decried Avant-garde #3 for “hooliganism.” The supplement to Literature and Arts began to publish the renunciations of members of Avant-garde in issue after issue. Some simply tendered their resignations from the organization; others claimed they had never even been members.

The “erotic poetess,” Troyanker, vowed to “crystallize a clearly proletarian ideology and to work on herself with great determination to destroy all undesirable traits” that being in Avant-garde had brought out in her. Others who left included Serhiy Tasin, Lev Kvitko, Borysov and Meitus, Dashevskiy and Bohuslavskiy, Nemolovskiy, and Kryha. Only Leonid Chernov, Mykhailo Pankiv and Vasyl Yermilov refused to renounce their friend and leader.

Two weeks before the New Year, Valerian Polishchuk wrote a letter to the editor that was published in the Communist Gazette in which he admitted his mistakes and decadence and took all the guilt for Avant-garde on himself. However, he insisted that individual mistakes should not be mixed up with the entire constructivist school, which should continue to develop in Ukraine. If he could have, Polishchuk would probably have said: “The Avant-garde is dead, long live the Avant-garde!”

[1] In soviet times, the term “hooliganism” was applied, not to punks in the streets, but to political, artistic and cultural dissent.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook