The cover of Universalny Journal (#6, 1929 – pictured), featured the painting by Ivan Padalko. The issue itself carried the following editorial commentary: “An error occurred on the cover of this issue of Universalny Journal as result of editorial sloppiness: a boy embraces a girl! This ideologically loose action is taking place against the backdrop of our capital with its smoking pipes and radio towers, to the powerful industrial rhythm of construction. The boy looks like a proletarian element. As to the girl, we don’t take upon ourselves to act as critics of fiction literature (who evaluate the morality of characters at first sight), yet we have to admit that this bourgeois-looking lady is embraced by an unrestrained worker student. The editorial board of Universalny Journal would never serve their readers such sentimental dish and, obviously, you will not find anything alike further on the pages of UJ. Yet, in truth, the boy has ridden to the countryside on his bicycle, and is in fact resting in nature with his machine. Even if anyone wants to see a girl, not a machine embraced by the boy, we kindly ask all our readers to immediately correct this unacceptable printing error on the cover of UJ.”

In the 1920s, Ukrainian readers enthusiastically wrote to authors, because there were no other ways to communicate with their favourite writers. The authors themselves encouraged this. For example, Valeryan Polishchuk and Oleksa Vlyzko even indicated their home addresses for feedback in their books. It was a kind of measure of success: how many people reply and whether they have praise or criticism.

Vasyl Mynko was literally bombarded with letters after the release of his story Belladonna. Fair female readers reacted to his book roughly the same way  that their modern-day equivalents do to Jane Austen: "I read Belladonna and couldn't sleep all night for crying…" Another time he was asked on a date. One passionate admirer wrote, "I will wait for you at five o'clock at the Central Post Office next to window 3. I will be wearing a green hat with Belladonna under my arm." Men wrote to him too, "Dear author Mynko. Where can I buy your book? I've been around all the bookshops in Poltava and everywhere they say that it's sold out." The joy and compliments melted the 26-year-old author's heart.

that their modern-day equivalents do to Jane Austen: "I read Belladonna and couldn't sleep all night for crying…" Another time he was asked on a date. One passionate admirer wrote, "I will wait for you at five o'clock at the Central Post Office next to window 3. I will be wearing a green hat with Belladonna under my arm." Men wrote to him too, "Dear author Mynko. Where can I buy your book? I've been around all the bookshops in Poltava and everywhere they say that it's sold out." The joy and compliments melted the 26-year-old author's heart.

The secret of his success was the genre. Romances were incredibly popular in the 1920s, as is confirmed by both the readership and circulation figures. At that time, no one knew this literary term or its colloquial meaning of "love affair", while critics branded such works petty bourgeois, vulgar, mundane and even sexual literature. Reviewers did not spare paper and ink for them. Oles Donchenko's Golden Spider, Vasyl Mynko's Belladonna and Hordiy Brasiuk's Donna Anna gave rise to dozens of comments, reviews and remarks, not to mention public debates that were never recorded.

About love once again

The new Ukrainian Soviet literature sought a "great novel", and when Valeryan Pidmohylny's City, Illness by Yevhen Pluzhnyk, Oles Donchenko's Golden Spider, Harmony and the Pigsty by Borys Tenet and Viktor Domontovych's Little Girl with a Little Bear came out at the same time in 1928, critics were at a loss. Where were the philosophical and ideological conflicts? Where were the images of proletarians? Where was the industrial subject matter?

Instead, an age-old and always relevant issue was troubling the young and old, men and women, Bolsheviks and non-party members. One critic wrote accusingly, "Mynko elaborates primarily and almost exclusively only one side of life – the relationship between women and men". At this time, well-known theatre critic Isaac Turkeltaub was attracting large audiences to a lecture course entitled Marriage and Free Love. The programme of these lectures was like a cheat sheet for the contemporary writer: take any topic and write a novel on it.

RELATED ARTICLE: How the Bolsheviks used identity to restore the empire

For many, a new life was starting in the 1920s, and no one knew what to take from the old one and what should be built from scratch. Marxist and feminist Olexandra Kollontai did not take reject the idea of love, but insistently developed a concept of a new woman – an independent personality whose interests are not confined to Kinder, Küche, Kirche, that is to say to the family, home and religion. The programme of Turkeltaub's lectures also covered many sore points of the time and even tried to identify the relationship between economics and sex. Admittedly, many of these issues have still not resolved. Here are just some of the most interesting ones: the essence of love; economics and the issue of sex; the family and marriage as an institution of oppression; the sexual crisis; forms of marital interaction (marriage, prostitution and free love); sex and class; new women of the bourgeoisie (the single woman, the fighting woman); the revolution and new morality; Soviet power and the problem of sex (a new Family Code); love and the working class; communism, love and the sexual crisis; social reforms and the potency of love; the ideal of "great love" and exhaustion with the past; monogamy or polygamy, free love or marriage?

The Civil War died down, a peaceful way of life took hold and a new economic policy was introduced; these issues inevitably cropped up on the pages of 1920s romance novels.

To the Young Communist – with an anxious love

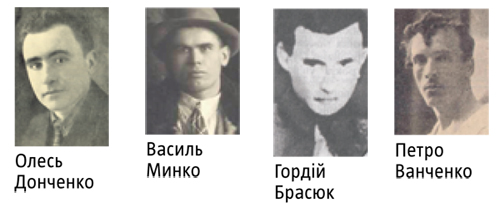

From left to right: Oles Donchenko, Vasyl Mynko, Hordiy Brasiuk, Petro Vanchenko

This unpretentious and unromantic dedication opens Borys Tenet's 1928 novel Harmony and the Pigsty. The main character Kateryna Lasko fights tooth and nail with the pigsty – the old way of life, its backwards and hypocritical moral code, the inequality of men and women in society, the quagmire of stagnation. She is a member of the Young Communist League, as is everyone else around her, but she is alone in her struggle. Kateryna pushes away a man she loves, because he is not ready for the harmony that she sees and belongs to the pigsty: "While there is a struggle, there is movement; while there is movement, there is nothing to be afraid of.”

That's why I don't want to be yours after all, Mykhailo, because love quickly fades, calms down and dies out.

I want to love in a way that will set the world on fire… Will you be able to do that, without deliberation? Nowadays, everyone in love lives through their brain, not the love itself."

There's your ideal of "great love" and of marriage and the family as institutions of oppression, especially for women. The woman is looking for new relationships and harmony, but men do not conform to her ideals and do not support her aspirations. The author loves his characters, the Young Communists, but with an anxious love.

RELATED ARTICLE: Baltic jazz in Soviet times

Oles Donchenko's story Golden Spider, also about Young Communists, came out in 1928 as well. Borys Tenet belonged to Kyiv literary group Lanka (Link), which was later renamed the Workshop of the Revolutionary Word. Its writers – Valeryan Pidmohylny, Hordiy Brasiuk, Yevhen Pluzhnyk – always gravitated towards psychologism and individualism, so they were immediately given up on. For them, a person with his joys, experiences and suffering – love, jealousy, betrayal – meant more than the entire Bolshevik idea or Soviet power. But Donchenko, a member of the literary organisation Molodniak (Youth), which was under the patronage of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Young Communist League, was qualified as someone who showed a lack of ideological self-control.

Oles Donchenko's story Golden Spider, also about Young Communists, came out in 1928 as well. Borys Tenet belonged to Kyiv literary group Lanka (Link), which was later renamed the Workshop of the Revolutionary Word. Its writers – Valeryan Pidmohylny, Hordiy Brasiuk, Yevhen Pluzhnyk – always gravitated towards psychologism and individualism, so they were immediately given up on. For them, a person with his joys, experiences and suffering – love, jealousy, betrayal – meant more than the entire Bolshevik idea or Soviet power. But Donchenko, a member of the literary organisation Molodniak (Youth), which was under the patronage of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Young Communist League, was qualified as someone who showed a lack of ideological self-control.

"Golden boy" of the twenties

The party came up with Molodniak in order to organise young writers and protect them from the influence of the older and already "lost" Mykola Khvyliovyi, Mykola Zerov and Panteleimon Kulish. The Komsomol writers' organisation originated in 1927 and immediately began publishing a magazine under the same name. Oles Donchenko's play Komsomol Wilderness was printed in the first issues, while the prose highlight of the magazine's first season was his story Golden Spider, which triggered heated debates in the Komsomolets Ukraine newspaper. The following year, the story was published as a book with a print run of five thousand copies; a year later another five thousand were printed, but the author was faced with a wave of negative criticism. Just the titles of the articles say it all: Ivan Momot's "In Search of Deviations", Andriy Klochchia's "What Is Opportunism and What Is a Hack Job" and "Biology Above All Else!" by Leonid Smilianskyi.

Although Komsomol writer Ivan Bahmut called Donchenko one of the most prominent figures of the new generation, this did not save him: any author who dared to raise the question of love and sex in the lives of young communists was accused of pornography.

The reviews of the writer’s "colleagues" from Molodniak were amazingly diverse. In Kyiv, Smilianskyi flew into a rage: "Donchenko has not realised that the relative importance of physiological moments in the life of the Young Communist League and Young Communists is nowhere near so significant, that it is not necessary to exaggerate when unveiling them, and that showing Komsomol only in this way means objectively reflecting decadent and bourgeois views on Soviet reality." In Kharkiv, Bahmut was full of praise: "Golden Spider has the ability to create a mood – the ability to make the reader live the life of the characters, to feel the subtlest nuances of their feelings and, ultimately, to awaken the reader's interest in certain everyday social issues and problems."

RELATED ARTICLE: How Ukrainians developed tolerance towards various religions

Based on the reviews, we get a sound piece of fiction on one and a story that could degenerate into a banal contrast between positive and negative types of Young Communists with an ideologically "correct" dénouement on the other. In the real story, the "good guy" Kolia Shpak manages to love his wife and have sex with another girl on the eve of her wedding, while the "bad guy" Volodia Bazylevych goes to prostitutes not only for sex, but also guided by his feelings.

A beautiful poisonous lady

The tips of spoof cattle farming professor Omelko Buts sometimes came in handy: "If you want to write a story, try to take a very interesting adventure from our lives and describe it in detail. For example, if the most interesting adventure in your life was the move from your native Zadrypanka to Kharkiv to study at the worker's faculty. You describe the interesting procedure of getting the ticket at the station, the train coach that you had never seen before, Kharkiv Station and so on. The more thoroughly you describe everything, the longer your work will be. You can write a novel in this way too."

Vasyl Mynko tried this recipe, changed it a little and made no mistake. In the mid-1920s, he was called up to the army and served in an aviation unit somewhere in Rostov. Then when the head of the Union of Rural Writers, which Mynko remained true to for many years, advised him to write about aviation once again, saying that it is great subject matter, the young writer fell to thinking: "But about what? I've already squeezed all the heroism out of myself. Perhaps about mechanic Ihor Dreus and his romantic adventures? Ihor's affair with a pilot's wife made a big fuss in the squadron where I served. In addition, knowing that I write a bit, Ihor gave me the diary of a prostitute who he kept company with. How is this not good material?

Two beauties of easy virtue, one idle and too well-off for her own good, the other… I thought about the name for a long time, in order to express the concept of the future story in one or two words. I go to the library, bury myself in an encyclopaedia.

‘Belladonna is a beautiful woman.’ And below, another meaning of the word – a poisonous flower. ‘It grows on rotten soils… The fruits of are bitter and salty, they have an intoxicating smell.’That's it! Exactly what we need".

Mynko's first book of prose brought him notoriety. In his characters' dialogues, he liberally used slang and colloquialisms: his "bella donna" Nina Serhiyivna calls the young pilot a "khokhlyonok" (little Ukrainian) and a "little devil", as well as singing romances and criminal songs. Events transform quickly, Mynko's moods, situations and actions are intricate, his endings unexpected. The adventurism, dynamism, Free Love and passionate scenes with the demonic woman were enough to have the novel deemed vulgar and cheap.

The body and signs of great love

Critics also regarded Petro Holota's stories Dirt and Entertainment as vulgar and cheap. Their content was considered worthless too, because, instead of  workers and villagers, the author described the life of the middle-class Halan family and the adventures of village boy Tolko-Anatoli, a libertine and seducer, in the city. Whereas Mynko took some lines from Alexandr Blok for the epigraph to his novel: of Blok "I feel odd myself and the world that I ignited is strange", Holota accompanied Entertainment with a passage by Sergei Esenin, which was even then considered to be the epitome of bourgeois tastes: "The body needs too much." And also gave the wholesome Young Communist girl in his novel magnificent breasts. The author was so carried away by her ample bosom that one critic called it a "dirty delectation", and Holota's novels – vulgar twaddle.

workers and villagers, the author described the life of the middle-class Halan family and the adventures of village boy Tolko-Anatoli, a libertine and seducer, in the city. Whereas Mynko took some lines from Alexandr Blok for the epigraph to his novel: of Blok "I feel odd myself and the world that I ignited is strange", Holota accompanied Entertainment with a passage by Sergei Esenin, which was even then considered to be the epitome of bourgeois tastes: "The body needs too much." And also gave the wholesome Young Communist girl in his novel magnificent breasts. The author was so carried away by her ample bosom that one critic called it a "dirty delectation", and Holota's novels – vulgar twaddle.

The characters in both Holota stories tried out all possible forms of interaction: official marriage, free love without commitment, even prostitution. Relationships in his romance novels, as the epigraph warns the reader, are very physical and often end with syphilis. Although, as Dr. Leonardo said in one of Mike Johansen’s stories, "What is syphilis, if not a sign of Great Love."

RELATED ARTICLE: The history of Kharkiv

The thing is, contemporary critics did not like this at all. As ill luck would have it, Petro Holota had an impressive career in the Party and at the end of 1920s belonged to Molodniak, as did Donchenko. During the struggle for Ukrainian independence (1917-1921), he joined the Komsomol in his native Yelisavetgrad (today Kirovohrad) and organised Young Communist centres in the province. At the same time, he started to be printed in local publications under the pseudonym Holota (his real surname was Melnyk) and soon became famous throughout the city: "When editors refuse to publish him, the Komsomol district commission writes a resolution on the poem: (in Russian) "Print immediately. The poem is imbued with revolutionary spirit. A failure to print would mean that you are shirking your duties.” In 1921, his first collection of poems, The Thorny Path to Freedom and Education, was released, published by the Yelisavetgrad District Commission of the Ukrainian Communist Party.

Komsomol writers had many problems with Holota. The Komsomolets Ukraine newspaper regularly reported on his weakness for alcohol, he twice spent time in prison for drunkenness and there was trouble in his family too. Add to that these novels with their "out-and-out", as reviewers liked to say, philistinism.

Indeed, Holota had no positive role models to offer: only philistines, shopkeepers, a meek communist who did not know what to do with his boisterous wife, an imposing official who rapes his servants, prostitutes who are satisfied with their profession, big spenders, thieves – in short, non-working and often criminal elements. Not the sort of adventures that a working rural reader expected from a Komsomol writer.

Life is a theatre

More often than not in the 1920s, romance novels did not revolve around banal love triangles, but were built on class contrasts: he was a Communist, she was bourgeois. Or the other way around: he was a White Guard, she a revolutionary. At the time, everyone was engrossed in Borys Lavrenyov's story Forty First, in which a female Red Army soldier, Mariutka, shoots a captive lieutenant she had fallen in love with in the back. In peacetime, love stories did not end so tragically, especially if class contradictions were tearing apart the hearts of proletarians and intellectuals.

In Yevhen Pluzhnyk's Illness (1928) and Tale Without a Name (1930) by Petro Vanchenko, party members fall in love with actresses. The plot develops while the theatre is performing on tour in the city. In both novels, the actresses desert their lovers and the unrestrained Bolsheviks conclude that they are wasting themselves on such wretches. Modest and steadfast company manager Ivan Orlovets recognises opera star Iryna Zavadska as the daughter of the factory director he worked for in his youth. Bolshevik and chairman of the City Council Radyvon Saran cannot find the right words to describe the feeling that has seized him, although the author gives us a clue: it was love – "a now abandoned feeling". Radyvon is faced with the severest psychological tests: a poor communist who had gone through the revolution and civil war, he is head of the city council, responsible party member and functionary with a wife and two sons. Pluzhnyk and Vanchenko have the same internal conflict and a similar clash of interests where even love is a disease and an ailment.

RELATED ARTICLE: The history of Odesa

Had he fallen in love? Radyvon Saran could not believe it himself, because love is for the youth and Young Communists, while he was an experienced, old Bolshevik, already 43 years of age. He is just as ashamed to admit that thoughts about his sons sometimes prevail over his state affairs. Indeed, nothing human is alien to the Communist and a beautiful woman, an operatic diva, awakens in him long-forgotten feelings and carnal desires. "Radyvon Saran fell in love with the operetta prima donna Kateryna Narosh. He came to this conclusion two weeks after his first meeting with her. At first, he could not understand what had happened to him and could not explain the reasons why he had lost his mind. Only later, observing himself and listening to Kateryna's allusions, he realised that this excitement and incomprehensible despair of his were leading to very serious events in his personal life and that they should be classified as love for that blonde girl."

Feelings versus duty and lover versus partner is another eternal dilemma. There is no talk of finding a female comrade, however, because neither his wife Olena, nor actress Kateryna share his views. His wife religious and superstitious, his mistress frivolous and empty, Radyvon is a lone wolf. He wrestles with himself, runs away from temptation and takes an assignment from the party committee to work in the countryside.

Maybe this is also part of Vanchenko's personal experience, as he participated in the civil war on the side of the Bolsheviks and fought against the Germans before taking an interest in theatre, performing on stage and leading the Union of Art Workers in Poltava.

The theatre is also the setting for key scenes in Arkadiy Liubchenko's story Contempt, which is about a Bolshevik who fell in love with a prostitute and made her his wife, but is willing to sell her to his boss in exchange for career advancement. Thanks to the artistic component, 1920s romance novels at the same time became examples of urban prose in Ukrainian literature.

The biology of love

What is stronger – ideology or physiology? Critics did not like the very question itself, because they felt that the answer would be even less satisfying for them. The issues that Turkeltaub raised in his lectures had very unclear answers in reality.

The worst thing was that this "vulgarity", as critics understood it, found its reader, thirsty for genre fiction. The novels by Donchenko, Pluzhnyk, Pidmohylny and Tenet were reprinted the following year. The total print run for Golden Spider reached 10,000 copies. Pidmohylny's City, which had conquered the hearts of literary critics, lagged behind by one thousand, but was nevertheless in second place: who would have thought this today! Belladonna and Tale Without a Name were never reissued, but 5,000 copies of each were printed outright. These numbers are sky-high for a country that was fighting illiteracy and in which only half the population could read and write (57.5% in the 1926 census). Even today's writers can only dream of such figures. And this was not only subsidised by the Ukrainian State Publishing House, but also the cooperative and private Syaivo, Ruch and Knyhospilka.

RELATED ARTICLE: Ukrainian state and elites in  he early modern era, 18-20th centuries

he early modern era, 18-20th centuries

Contemporary Soviet critics did not notice the birth of popular literature before their very eyes: not only in terms of circulation (political leaflets had seen much bigger print runs), but also as a genre. In the second half of the 1920s, the first adventure and science fiction novels appeared, as well as detective stories and melodramas that can be safely be called romance novels. The latter are host to an expressive melodramatic intrigue with characteristic motifs of love, betrayal, villainy and hypocrisy, alongside conflicts in the search for genuine people and feelings.

The genre of romance novel dictates certain requirements: it must be a romantic story about a relationship, inevitably with a happy ending. Jane Austen would have cried her eyes out reading Mynko's Belladonna or Brasiuk's Donna Anna with their dramatic twists and surprising, not at all joyous conclusions. This is what makes the 1920s romance novel interesting: not the repetition of genre clichés, which a modern reader is used to and expects, but the original and unexpected innovation, as well as the combination of melodramatic stereotypes with the new economic Zeitgeist and… eroticism. What now seem like innocent allusions to sex were blatant pornography for critics 90 years ago.

Various types of people appear in the romance novels of the time. The young and old; educated and barely literate; with different origins: commoners, intellectuals, villagers, party members, Young Communists; with various professions: officials, workers, prostitutes, engineers, artists, musicians, pilots. However, they are all subject to ordinary human feelings: they are able or unable to love, they are jealous, have fun and play with other people's feelings, flirt, intrigue, desire, cheat and are cheated on, hate and look for revenge. They can be funny or scary, pleasant or repugnant, but always evoke emotions. A sort of fanciful, capricious love, not subject to party guidelines on biology.

Romance novels of the 1920s also vary stylistically, as each author is endowed with different writing talents. However, they are not sentimentally sappy, and not even romantic, as is fitting for the genre. Nevertheless, they give us a more or less clear notion of the mass fiction that was popular at the time, in which romance novels played a leading role.

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook