From the time that the Christian church came to dominate Europe, education was largely religious and oriented towards denominational and often missionary needs. The church was the institution where formal education could be obtained and the clergy were the educators. Any alternatives were persecuted and punished. However, medieval schools should not be viewed as something retrograde and horrible, as institutions that used physical punishment and had exclusive gender orientation (education for males) with rigid Latin, rather than the vernacular, as the language of instruction.

THE NEW LEARNED WORLD

In fact, the “old” school was the starting point for great transformations: the recognition of the value of learning, education and books; attention to grammar and knowledge in general; the significance of writing and the written word; the first specialized education institutions and so on. The essence of education in the old days was not reduced merely to scholasticism: there was a huge layer of vocational training (when a master craftsman taught his apprentices the tricks of the trade) and folk pedagogics. In the 13th century, urban schools funded by municipal communities emerged in Europe. At the same time, the majority of the population of the Middle Ages was completely illiterate, and learned men were often held in contempt or accused of heresy or witchcraft.

Medieval education in Europe reached its peak when education left the premises of churches and monasteries. Homeschooling spread and universities were opened. The idea of providing multifaceted knowledge was evidently borrowed from the Muslim world – contact with Muslims during the Crusades fundamentally changed Western Europe. The first universities in the Old World were former church schools in Bologna, Oxford and the Collège de Sorbonne in Paris (named after its founder, Robert de Sorbon). The very lifestyle of bachelors and students and their conduct formed a unique subculture. In England, the word bachelor (from Latin, meaning ‘crowned with laurels’) became synonymous with an unmarried man or even a tramp.

When this new “learned world” came into contact with the local population, it often led to extraordinary events with ambiguous consequences. For example, a conflict between, on the one hand, students and faculty and on the other, Oxford residents in 1209 causing part of the faculty to move to Cambridge where England’s second university was founded.

IN THE ARENA OF RELIGIOUS CONFLICT

In this context, Ukrainian lands were a distant province of Europe. The adoption of Christianity from Byzantium, with its Orthodox tradition of schooling, defined the future development of education in Ukraine for many years. At the same time, the main appeal of Ukrainian culture in the early Modern Age, namely the sustained combination of Western Catholic and sometimes Protestant influences with the dominant Orthodoxy, was vividly and best manifested in education. In the 16th and 17th centuries, education became the arena of fierce religious conflict, laying the foundation for Orthodox brotherhood schools and printing houses.

In the Ukrainian context of the early Modern Age, the words school and student had wide social significance. Schools were often institutions or buildings attached to churches, which offered not only the basics of reading and writing but also provided a kind of shelter for beggars and “perpetual students”.

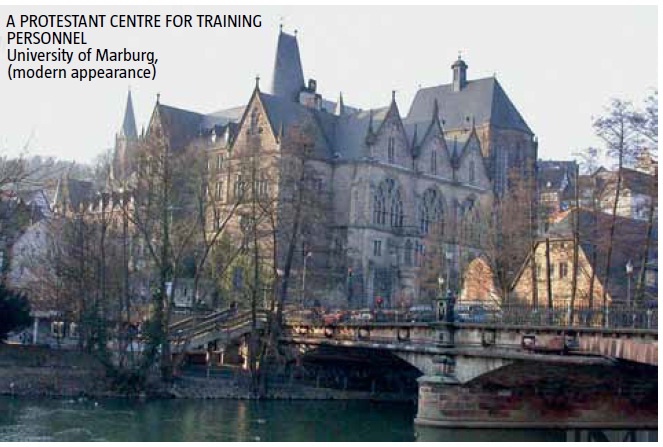

However, it was the learned clergy that later became the source of great changes. Ideas, often produced by theologians, eventually led to the great Reformation, a rebellion against the Catholic Church, and gave a new meaning to education. Protestants – or in the case of Ukraine, Orthodoxy – had to have perfect education and their own fully-fledged education institutions in order to be able to debate religious topics with highbrow Catholic theologians. The first harbinger was the Protestant University of Marburg in Germany, opened in confiscated monastic cells by Landgrave Philip I of Hesse in 1527. In Ukraine, we have the example of the Ostroh Academy, which was founded by Kostiantyn Vasyl Ostrozky in 1576.

The invention of the printing press also had a major impact on education. As the print-runs of books and textbooks grew and their educational potential increased, the ideas of and demand for education spread under conditions of drastic socioeconomic change.

In its turn, the Catholic Church introduced a wide system of education institutions run by the Jesuits (Jesuit collegiums), offering accessible education to students, often regardless of their financial situation or professed faith. The collegiums in Lutsk and Ostroh were among Ukraine’s leading education institutions in the 17th and 18th centuries. The Orthodox education system often followed their example. The first university on Ukrainian territory was founded in 1661 in Lviv, thanks to the Jesuits. The curricula at Orthodox and Greek Catholic institutions were based on what was taught at Jesuit collegiums.

Learning. Medieval engraving

EDUCATION GOES SECULAR

In addition to the Reformation, the idea of education rested on another powerful pillar – humanistic philosophy, with its special attention to man as the crown of creation. John Amos Comenius (1592-1670) made a breakthrough in pedagogics and changed the overall attitude towards education. His key ideas became the foundation for the introduction of new teaching methods: overall comprehensive education in the native language, differentiation by age, the concept of higher education and particular attention to individual aptitudes. However, all these trends were embodied all too slowly in the European world over the next couple of centuries.

At the same time, in the 16th and 17th centuries, religious education saw the emergence of serious rivals. The Collège de France was founded in 1530 with the support of King Francis I of France and offered disciplines not available at the Sorbonne. In fact, increased competition in education and science and the dissemination of printed books helped France maintain intellectual leadership in the world in the 17th through early 19th century. French thinkers launched the Enlightenment, a new philosophical movement aimed at not only rational explanations of phenomena but also at fighting religious obscurantism, giving education a leading role in the process.

READ ALSO: Reflections From Afar

Learned men from Ukraine were, in many respects, the main motivational force in education reform in the Russian Empire. After church reform and the adoption of the Ecclesiastical Regulation in 1722, Peter I set about changing the Russian education system. Teofan Prokopovych, the mastermind behind the reform, used the Kyiv Mohyla Academy, where he had previously taught, as a model for ecclesiastic education reform. In Ukraine, this system had a solid foundation: the Kyiv Mohyla Academy was already functioning on these principles, the Chernihiv Collegium was expanded, a new collegium was founded in Belgorod in 1726, which was later moved to Kharkiv and the Pereislav Collegium was established in 1734. These institutions were special in that, for a number of reasons, they admitted representatives of the most diverse social strata. In contrast, the formation of the class structure in imperial society, required a narrow class approach to education.

The founding of new schools came at a time when many European countries adopted a secularization policy. Its primary goal was to transfer church property to the state, but it also envisaged a network of secular education institutions to replace ecclesiastic ones. The latter were given the role of educating would-be priests, most often children of the clergy. While secular education, based on rationality, was taking over in Western Europe, Ukrainian lands remained captive to scholasticism for years to come. This largely determined the future development of education in Ukraine.

Disobedient children. German caricature of schools, 1849.

For the most part, not surprisingly, Russia’s reformist efforts in education followed German examples. Mikhail Lomonosov, the main Russian promoter of the Enlightenment, who initiated the establishment of Moscow University, obtained secular education in Marburg. Under the 1782-86 education reform, public schools were opened in every provincial and district centre in line with the Austrian model. Subsequent Russian innovations with universities were based on the Prussian experience of reform and the Humboldtian university concept. Inviting professors, primary of German origin, from abroad, was another factor that contributed to the significant German influence on many initiatives launched by the Romanov family. Not all imperial education reforms of the late 18th century, especially on Ukrainian territory, were successful or even finalized. They often remained on paper only. One case in point was the intent to open a large university with a medical school in Katerynoslav in the 1790s.

READ ALSO: Our Сhildren

The reform started by Alexander I in the early 19th century caused sweeping changes in the education system of Ukraine, which was under Russian rule at the time. It laid the foundation for the future three-level system: primary (vocational schools), secondary (district and secondary schools) and higher (universities). This innovation also helped make education accessible to women, even though student bodies in education institutions continued to be dominated by men for a long time. These changes signalled a high overall goal – free primary education for all classes. The Ministry of Public Education was set up to implement the plans.

Despite the progressive nature of these changes, Ukraine’s education system was directly dependent on the centre of the empire, and was not only a matter of banning or tolerating cultural-ethnic differences. In tsarist Russia, a university diploma was the springboard for a bureaucratic career, rather than evidence of acquired knowledge. Education received abroad played an important part, because it was considered to expand one’s worldview and was often a prerequisite for successful professional activity.

ALMA MATER

Kharkiv Imperial University, founded in 1804, was the first large secular education institution on Ukrainian lands. The academic year began on Saint Anthony’s Day, 30 January 1805 (however, modern Ukrainian students celebrate 25 January, Saint Tatiana’s Day, as their holiday. On this day in 1755, an edict was issued to establish Moscow University). It was in Kharkiv that the national revival of Ukrainians began, under the influence of Ukrainian teachers and students.

During the 19th century, Russian imperial authorities opened two more universities in Ukraine; in Kyiv in 1834 and in Odesa in 1865, as well as a number of other education institutions. However, knowledge spread at a languid pace, and Ukrainians as an ethnic group had the lowest level of education in the European part of the empire. All of this made the Ukrainian intelligentsia idealize the times when brotherhood schools and Orthodox collegiums operated and emphasize the destructive role of the “lost time” Ukrainians had spent in the Russian Empire. To Ukrainian intellectuals, education delivered in Ukrainian was a great goal and a powerful tool with which to press for further changes.

READ ALSO: How to Bring Up a Ukrainian-Speaking Child

At the same time, the Ukrainian lands that were under the Austrian-Hungarian Empire also underwent several education reforms. In addition to Lviv University, in which the teaching language was Polish, Chernivtsi University was established in 1875, offering classes in German. The struggle of Ukrainians to have their own university in Galicia is an important page in the history of the national movement.

Both parts of Ukraine experienced similar problems with education in the 19th century: low accessibility and a limited number of even primary schools, which greatly complicated both economic development and social communication. The efforts of Moscow and even permission to open Sunday and private schools starting in the 1860s did not resolve the problem, at a time when primary education was becoming compulsory in England and the Netherlands and played a key role in unifying Germany.

EDUCATION AS AN IDEOLOGICAL PLATFORM

The events of 1917-20 led to major shifts in the education system in Ukraine. More than just nationalization, they included large-scale experiments, especially on the territories under Bolshevik rule. As they tried to do away with the vestiges of the old regime, the new ruling power filled education with ideology and fundamentally changed higher learning, replacing universities with “institutes of public education”.

However, a true breakthrough came in 1920 when the anti-illiteracy campaign was launched and class and sex distinctions that gave privileged access to education were abolished. The indigenization policy required that the peoples making up the Soviet Union obtained an education in their native language. The Soviet system exploited education as an ideological platform for creating citizens loyal to the regime.

RAISING A NEW PEOPLE. Having made education universal, free and compulsory, at the same time, the Bolsheviks also impregnated it with ideology, cutting it off from worldwide education processes

However, abandoning the old, “pre-revolutionary” education institutions and establishing a new system was hampered by a lack of adequate cadres. Therefore, universities were restored in the early 1930s. The Stalinist model of higher education had little in common with the earlier imperial one and became the basis for the contemporary Ukrainian university system. The USSR focused on personnel training, leading to the widespread myth about the high level of Soviet education, which, however, failed in competition with the Western world and was one of the causes for the demise of the Bolshevik empire.

The Soviet education system experienced several major reforms. One milestone was the law of 1958 on “strengthening the link between school and life” which introduced 11-year secondary education, of which 8 years were compulsory. The focus of attention was on “professionalization”, i.e., the training of production workers who were still in school. The experiment was a flop, and 10-year secondary education was reinstated in 1964-65 with less emphasis on vocational training but with the compulsory component intact.

READ ALSO: Alma Pater

The Ukrainian model of education evolved from its Soviet predecessor, but a large number of reforms in the past 20 years have failed to solve its burning issues, such as training a qualified labour force and helping students realize their potential.

DIFFERING INTERPRETATIONS

East Slavic languages differ in the ways they designate the knowledge acquisition process. The Ukrainian language adopted the word osvita ‘education’, from svitlo ‘light’ and osvichuvaty ‘to throw light on’, probably prompted by major figures of the Slavic revival. In contrast, the initial Russian word prosveshcheniye, also based on the idea of light, yielded to obrazovaniye, was copied from the German Bildung, literally the shaping of new man. The latter coinage later coincided with the goals of the Bolshevik government.