From the very beginning of its rule, the current government laid the foundation for the concept of its cultural policy by criticizing “Orange nationalism,” but it was clearly not enough to make the construction stable. Consequently, these modern ideologues were forced to pull out one brick after another mostly from the established myths of the past. Now they are clumsily but intensively putting together a cultural Frankenstein from the fragments of Soviet ideology, some idea about the “Russian World” and a grotesque vision of Ukraine. The impression is that our identity is being targeted, because most of the damage is being done to such cultural domains as the language, history, the commemoration and memorialisation policy, education, etc.

The topics of the Holodomor and the UPA were used as keys to constructing national identity in the Orange period, so the first changes affected precisely these topics. Viktor Yanukovych’s public denial, in Brussels, that the 1932-33 Holodomor was genocide against the Ukrainian people; the stripping of Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych of their Hero of Ukraine titles; and the restored practice of pompous military parades on Victory Day and even the government's silent assent to a monument to Stalin in Zaporizhzhia – these are an incomplete list of innovations that signal cardinal changes in the policy of how Ukrainians are to remember their own history.

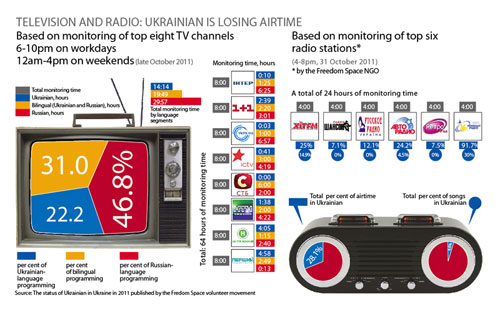

As far as the Ukrainian language is concerned, the “new course” can be seen with the naked eye: Russification on the level of individual regions; decisions by local administrations to use Russian; a noticeably smaller place for the state language even in linguistic sectors like education, etc. Sensing this new trend, mass media outlets greatly reformatted the information space which led to a reduction in Ukrainian-language production, the domination of the Russian language on television and the prevalence of Russian or Soviet content (largely propaganda) on Ukrainian TV channels.

THE POLICY OF HISTORICAL AMNESIA

All government agencies and institutions that actively dealt with problems of the past in 2006-2010 later experienced major personnel reshuffles and sometimes structural transformations. For example, the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory (UINM), which, despite all its drawbacks and mistakes, was on its way to becoming a leader in forming the government’s policy in this field, was saved from being shut down only due to pressure from the public. But the government used the old principle “If you want to destroy something, head it!” On December 9, 2010, Viktor Yanukovych issued a decree to reorganize the UINM from a central executive body into a research institution attached to the Cabinet of Ministers, which significantly reduced its powers. This made the UINM largely irrelevant in the structure of public administration. Experts dubbed the presidential decree “the final stage of eliminating the state policy on national memory in Ukraine.” Moreover, this institution is morally unable to deal with historical memory, because on 19 July 2010, the Cabinet of Ministers appointed Valeriy Soldatenko (photo) its director. Until recently Soldatenko was an ideologue of the Communist Party of Ukraine and was directly involved in drafting its new programme.

Absurdly, a communist is now running an institute tasked with unmasking the anti-human past actions of communists. The State Archive Service is still headed by another communist, Olha Hinzburh, who infamously said that restoring historical memory “may harm descendants.”

THE ARCHIVES OF ABANDONED SECRETS

In 2008-2009, the SBU State Archive became actively involved in implementing the policy of historical memory. It began to declassify documents of Soviet security bodies about the Holodomor, Stalinist repressions, the OUN and the UPA. The archive became open to a large extent. An electronic database of documents was set up. Dozens of academic articles, collections and exhibitions were prepared. However, the archive, which has exceptional historical value, has remained under the control of the Security Service.

The archive’s public activities have been discontinued. Sources are being published extremely selectively. Access to a part of previously declassified documents of Soviet punitive bodies has been limited. Transferring the historical part of the KGB’s documentary legacy to the state archives is no longer on the agenda. Instead, Yanukovych issued a decree in June 2011 to reorganize the SBU’s Department for Archival Provision into an archival institution attached to the Security Service.

On 12 January 2012, the Verkhovna Rada passed in the first reading amendments to the Law “On the National Archival Fund and Archival Institutions” which opens a possibility of destroying archival documents that have lost their cultural value, have duplicate copies or are irreparably damaged and cannot be restored. This new law also permits limiting access to documents containing “confidential information” for 75 years after the time of their creation. Experts say that archival institutions interpret the concept “confidential information” arbitrarily and expand its scope for no good reason. This kind of law on archives will give the government convenient tools to cut off access to Soviet-era sources.

CLASSIFIED. The new law on archives is a convenient tool to cut off access to Soviet-era sources

At a press conference about amendments to legislation initiated by the State Archival Service of Ukraine, its chief Hinzburh (in the photo) thus replied to an expert who asked her about implementing European standards of transparency: “We have become so open that if it were up to me, I would close half of it.” Shortly before she made this statement, Yanukovych expanded her powers by appointing her a state expert on the issues of secrecy. Now Hinzburh is authorized to classify information as a state secret, change its status and declassify documents.

According to a poll carried out by experts from the Centre for the Study of the Liberation Movement, 86.2 per cent of researchers in Ukraine have faced difficulties with obtaining access to archival documents in the past two years.

A HISTORY OF LITTLE RUSSIA FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

Several school and college textbooks recently found themselves in the focus of public attention. One was a Russian-language handbook, Ocherki istorii Ukrainy (An Outline of the History of Ukraine), edited by Academician Petro Tolochko and intended for higher education institutions as an alternative to the “Orange model of history.” It allegedly took the authors five years to write it, but they were unable to publish it for a lack of funds. The textbook was praised by all “anti-Orange” forces – from Communist Party members to Russian nationalists. For example, the newspaper Kommunist published a review which lauded the text as a “return to the truth” and referred to one of the chapters as “the restoration of the historical truth about the Great Patriotic War.”

In contrast, Ukrainian scholar Olena Rusyna, who analysed only the “Lithuanian” period in the volume, accused the authors of compiling data from the textbook on the history of the Ukrainian SSR, pursuing a political agenda and being biased. Historian Kyrylo Halushko pointed out that the texts in the book were written in different genres, were not internally coherent and lacked an overall conception. He also outlined lame attempts to argue for the existence of an Old-Rus’ community and Ukrainian-Russian unity throughout Ukraine’s history (see The Ukrainian Week, Is. 37, 2011). Historians said tongue-in-cheek that, using this approach, Tolochko could be expected to produce A History of Little Russia within a year or two.

The content of school textbooks was also modified to fit the new political situation and the historical preferences of the current government. For example, several episodes were removed from Viktor Mysan’s textbook for the 5th form: the Battle of Kruty, the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen and the UPA’s struggle against the Nazis. Unbeknownst to the author, mentions of the Orange Revolution and the 2004 and 2010 elections were also crossed out. In general, he was asked to make changes that would form “a non-aggressive image of Russia.”

Since September 2011, students in the 11th form study the history of Ukraine according to new textbooks. Initially, three authors won the competition organised by the Ministry of Education – Olena Pometun, Oleksiy Strukevych and Stanislav Kulchytsky. However, government financing was later suddenly withdrawn for Kulchytsky’s book under the pretext of “insufficient funds.” In the new textbook “Great Patriotic War” again “replaced” the Second World War, while the OUN and the UPA were barely mentioned at all. The term “Orange Revolution” also disappeared – Pometun says no such revolution ever took place. The description of these events is reduced to a minimum.

In October 2010, Education Minister Dmytro Tabachnyk announced that a working group would be put together to prepare a joint Ukrainian-Russian textbook for history teachers following an agreement he had made with his Russian counterpart. Aleksandr Chubarian, Director of the Institute of World History (Russian Academy of Sciences) and one of the leaders of the group, said that the sides had already agreed not to involve “extremist” scholars in the process. (Evidently, this means anyone whose views are not in line with the pro-Russian position.)

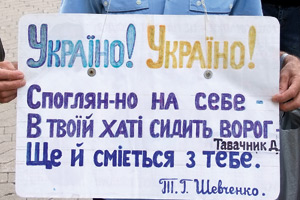

Recently, the mass media reported that the Ministry of Education intended to integrate two school subjects – History of Ukraine and World History – into one, thus dissolving topics about Ukraine in the general presentation of history. On 20 February, Tabachnyk denied this as “an absolute lie” but said that a project to this effect was being developed by “a group of scholars from the National Academy of Pedagogical Sciences.” It will be submitted for evaluation to the ministry upon completion. He added that officials were pondering a possible reduction of academic hours for the Ukrainian language, literature and history in forms 5-11 allegedly in order to allocate more time to foreign languages (including Russian) and computer science. Evidently, the ministry has the goal of eliminating the national foundation of Ukrainian education.

THE SPREAD OF SOVIET PROPAGANDA

The legislative initiatives of the Verkhovna Rada in the field of memory policy in the past two years are hard to call anything but inadequate, incompetent and sometimes intentionally provocative. One of the scandalous events in 2011 was the celebration of 9 May in Lviv which evolved into a fight. Prior to that, on the initiative of the communists and the Party of Regions the Ukrainian parliament passed a law under which red flags were to be used next to Ukrainian national flags during the 9 May celebrations. Ukrainian society was outraged. Experts said that the Law “On the Victory Flag” was a direct borrowing from the Russian legislation. The city councils in Ivano-Frankivsk and Lviv banned flags with Soviet symbols on 9 May. Instead, “veterans” were brought from eastern regions to Lviv in order to “unfurl the red banner.” All of this led, for the first time since independence, to direct physical violence and the use of traumatic weapons.

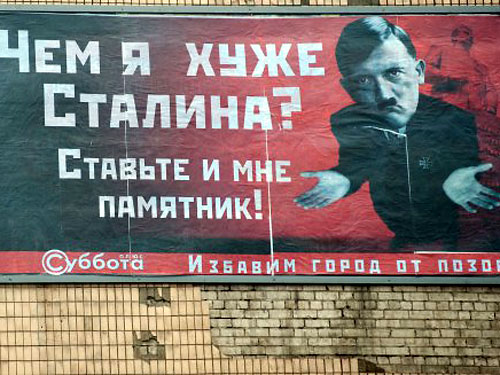

The new government has been persistently acting through parliament to introduce in Ukraine the old Stalinist models of war memories that are now being restored in Russia. Tellingly, the Verkhovna Rada passed a resolution to mark the 65th anniversary of the Nuremberg Tribunals on the initiative of the Party of Regions, the communists and the Volodymyr Lytvyn Bloc. Following the Russian Duma, the Ukrainian parliament denounced comparisons between Stalin-ruled USSR and the Third Reich. Ukrainian MPs said it was immoral to blame the USSR for starting the Second World War in the same way as Nazi Germany. Western countries were to be presented as the instigators of the worldwide conflict; the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had to be rehabilitated, and Stalin’s image whitewashed. The resolution also denounced attempts to “justify collaborationists".

Why am I any worse than Stalin? I want a monument, too! Drive disgrace from our place! A creative billboard put up by Zaporizhia-based journalists attracted public attention but only for a short while

At the same time, in addition to stigmatising “foreign heroes” the Party of Regions is trying to rehabilitate and popularise “our own.” In October 2011, the Verkhovna Rada approved a draft resolution sponsored by Oleksandr Yefremov, leader of the Party of Regions faction, on state-levels celebrations on 70th anniversary of the underground youth organisation Young Guard, which was created on September 28, 1942. In this case, the problem is not just childhood nostalgia and the Soviet mentality of the Party of Regions. The list of planned events, apart from traditional points like as fixing up museums and monuments noteworthily, the publication of Alexander Fadeyev’s novel The Young Guard despite the fact that its historical underpinnings were recognised as falsified long ago. The author was guided by Stalin in writing the text. This typical specimen of socialist realism began to be reprinted in Russia only under Putin (in order to instil patriotism in the young generation), and now Ukraine is going to follow suit.

According to amendments made by the Verkhovna Rada to Article 2 of the Law “On Commemorating the Victory in the 1941-45 Great Patriotic War” in December 2011, the government will please Ukrainian citizens with free feature films and documentaries about the war in state-owned and community cinemas and cultural institutions on 9 May 2012. In this way, Ukraine will spend budget money to broadcast on television and show in cinemas the products of Russian propaganda with massive promotion of a number of myths about the “Great Patriotic War” for the purpose of their further conservation in society.

The childhood nostalgia of the Ukrainian establishment for the totalitarian past led to a series of reincarnations in the Ukrainian media space. Such Stalin- and Brezhnev-era hits have been shown as Bolshaya zemlia (The Ural Front), Timur i yego komanda (Timur and His Team), Vstrecha na Elbe (A Meeting on the Elbe), Pyatyi okean (The Fifth Ocean), Bolshaya zhyzn (A Great Life), Dva boytsa (Two Fighters), Admiral Nakhimov, etc. In addition, Ukrainian viewers get to watch talk shows about the war that involve spin doctors and so-called government "historians".

ALWAYS ON GUARD. Serhiy Yefremov is known for fiercely fighting “Ukrainian Fascism”

THE SCIENCE OF HATRED AND A PERSONALITY CULT

A confrontation of identities fuelled by the government is also being promoted in the practice of memorialisation. For example, in what was an open defiance of the Orange government’s policy to rehabilitate nationalist heroes, eastern Ukraine set up monuments to “victims of the UPA,” i.e., civilians and NKVD officers from eastern regions who died when the Soviets were subjugating western Ukraine.

On 14 September 2007, the first such monument was erected in the central square in Simferopol. It was named “A Shot in the Back” and dedicated to “the victims among the Soviet people who died at the hands of Nazi collaborators,” meaning the OUN and the UPA. Such monuments have been springing up in villages across Sumy Region. A monument to Soviet victims of the UPA was restored in May 2010 in Luhansk. This artefact has a patently provocative and confrontational nature. The anti-UPA theme was taken a step further in Donetsk where a monument to General Nikolai Vatunin “killed by the Banderites” was set up.

The monument to “victims of the OUN-UPA” erected by the Luhansk authorities

Attempts to restore the cult of Soviet tyrant Joseph Stalin in eastern regions of Ukraine was an even more radical antithesis to Ukrainian historical memory. On 5 May 2010, a bust of Stalin was installed in the territory of the Communist Party committee in Zaporizhia with the authorities doing nothing to stop it. On 28 December 2010, his head was sawed off by unidentified persons, and the pedestal was blown up on New Year’s Eve. Later, during a prosecutor’s investigation, the sculpture was presented as “a decoration of the building” rather than a monument. The authorities carried out arrests in the local branch of the Tryzub (Trident) organisation and sentenced nine people to 2-3 years in prison in December 2011. On November 7, 2011, the communists restored the scandalous bust despite protests from the local community.

INSTIGATOR OF UKRAINOPHOBIA. Vadym Kolesnichenko speaks at the opening of exhibition “The Volyn massacre: Polish and Jewish victims of the OUN-UPA”

DE-UKRAINISATION OF EDUCATION

Public monitoring suggests a premeditated policy aimed at limiting the use of Ukrainian in education. According to the overview “The condition of Ukrainian in Ukraine in 2011,” the number of first-year school students in Russian-language schools grew in southern and eastern regions. For example, the share of such students in Kherson Region in the past school year was 1.9 per cent higher than the average figure for all students. In Luhansk Region, the percentage of first-year students in Ukrainian-language classes dropped by 4.7 per cent. This is one of the consequences of processes that started in 2010: the closure of Ukrainian-language schools and widespread inclusion of Ukrainian-language schools in the category of bilingual institutions (with Russian-language classes). For example, the Odesa City Council passed a decision to make School No. 124 officially bilingual. In other words, the gradual transition of school education to Ukrainian-language instruction, which had continued for 20 years, was essentially halted in many regions. In addition to censoring the way the history of Ukraine is taught, literary works about the Holodomor, including Vasyl Barka’s Zhovtyi kniaz (The Yellow Prince), were removed from the school curricula and external testing.

DRIVING UKRAINIAN OUT OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN

The domination of Russian is noticeably increasing in the public sphere in Ukraine. According to the Space of Freedom movement, the print run of Ukrainian-language books and brochures dropped from 27,527 items per 1,000 citizens in 2009 to 15,094 items in October 2011. At the same time, the total print run of newspapers published in Ukrainian fell from 32 per cent in 2010 to 30 per cent in 2011, while that of Russian-language newspapers grew from 63 per cent to 66 per cent. Russian is also dominating on television. According to the Space of Freedom, which monitored the most watched TV channels, Ukrainian accounted for a mere 22.2 per cent, bilingual programming for 31 per cent and Russian-language broadcasts for 46.8 per cent. The same is true of the radio: six top radio stations spoke Ukrainian 28.1 per cent of the time, while the share of Ukrainian-language songs was a miserable 4.6 per cent. A law was passed in late 2011 which scrapped quotas for Ukrainian music for radio and television broadcasters and reduced the quota for Ukrainian audiovisual products from 50 per cent to 25 per cent.

TV IS DUMBING DOWN UKRAINE

According to various estimates, Ukrainian television has increased entertainment content by 2-3 times and proportionately reduced intellectual programmes in the past two years. The main prime-time content is low-quality Russian TV series. A parallel reality is being modelled, and this trend, which has been tried and tested by Russian TV channels, is picking up steam in Ukraine. According to TeleKrytyka and the Institute of Mass Information, there is a growing number of topics that are given superficial treatment or ignored altogether by television, such as an attack against business and freedom of expression, the activities of the government and power structures, the dropping standard of living, protests and court injunctions banning them, the falling popularity ratings of the powers-that-be and the persecution of the opposition. In particular, in November 2011, the 1st National Channel led the way with 166 items on sociopolitical topics that looked like they had been ordered (or censored). The 1st National Channel, the New Channel and Inter are the channels to most frequently ignore of important topics with 468, 467 and 466 cases respectively in November 2011. Inter and ICTV had the first place in refusing to report on the curtailment of freedom of expression by ignoring 27 such episodes each. Most TV channels have offered unbalanced coverage of trial proceedings against opposition leaders and the activities of opposition parties. One of the most recent examples was when the biggest television broadcasters ignored the demarche of Afghan war veterans who turned their backs to the president when he came to lay flowers on the anniversary day marking the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan.