At first glance, it may appear that there are no similarities between the Ukrainian classical theatre of the 19th century and the avant-garde Ukrainian cinema of the 1920s. On the surface, they seem to be completely different, with unique aesthetic codes, societal orientations, and political principles. The years of turmoil marked by military and revolutionary upheavals separate them, making them appear as polar opposites. However, upon closer inspection, you can observe their closeness, affinity, and, ultimately, their resemblance to relatives of different generations. For instance, one could think of them as a grandfather and his grandchild who have opposing tastes and preferences and tend to argue frequently. But they eventually converge on something essential – their fundamental values. It is important to highlight the strong connection between the old theatre and the new cinema, which played a significant role in developing Ukrainian culture despite its obscurity. Mykola Karpovych Sadovsky is a highly esteemed figure on the Ukrainian stage who served as a link between these two artistic phenomena that were separated by time and ideology. He started his film career in the early 1910s and managed to appear in two films at the end of the 1920s.

Filming Theatrical Performances

Mykola Sadovsky was a representative of the star generation of Ukrainian artists, whose mastery of performing musical-dramatic, romantic-ethnographic, realistic-naturalistic plays was considered unparalleled.

He was the first among his generation to recognise that the era of the theatre was fading and the era of cinema was dawning when he was well into his fifties. In 1911, Sadovsky saw the potential of filming theatrical performances to later show them in cinemas. He probably didn’t know that an American director named David Belasco was also doing the same thing around that time.

David Belasco

Sadovsky did not have a studio like Belasco did. However, during the summer tours of his Kyiv theatre in Katerynoslav, he was able to film performances. He responded to a proposal from a local cinematographer named Danylo Sakhnenko, who worked for the film company “Khudozhnist” (“Artistry”) of Isaiya Spector. This led to Sadovsky filming popular theatrical performances. Sakhnenko worked as a correspondent for Pathe Freres, a renowned French company. He used the cinema camera obtained from the company to shoot news and artistic films. Andriy Kordyum, who later became a Ukrainian film director, assisted him as a motorboy. In the late 1920s, Kordyum invited Sadovsky to play the final role in his film.

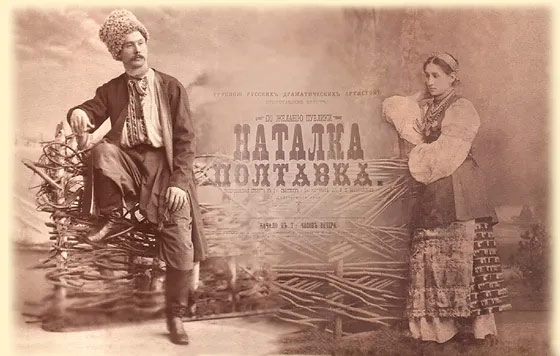

As a first step, they decided to film two successful plays: the comedic opera “Natalka Poltavka” by Ivan Kotliarevsky and the melodramatic play “Maty-Naymychka” (“The Servant Mother”) by Ivan Tohobochny, based on a poem by Taras Shevchenko. They invited well-known Ukrainian actors to participate in the filming, including the renowned leading actress on the Ukrainian stage, Maria Zankovetska. At that time, she had stopped performing at Sadovsky’s theatre; however, she had agreed to play the role of young Natalka in a film performance alongside her longtime partner, Mykola Sadovsky. She came to Katerynoslav to take on this legendary role at the age of fifty-seven.

Mariya Zankovetska and Mykola Sadovsky. Source: www.tmf-museum.com

The film crew set up their equipment on the outdoor stage of the summer theatre located in the City Garden. Shooting began early in the morning before any audience members arrived. Sadovsky was the director of the production and had full control over the mise-en-scènes, shaping them according to his personal taste and vision for the film.

To achieve greater authenticity, instead of the usual theatrical backdrop, additional picturesque canvases and decorations were installed, and Dmytro Yavornytsky, a well-known researcher of the Cossacks, lent real weapons, authentic clothing and household items for the shooting.

In December 1911, two films were released, gaining immense popularity and continuing to be distributed until the mid-1930s. These films were so popular that they were shown until the film copies were completely worn out. According to a film historian, the remaining frames of the films were even assembled and shown in the villages of the Dnipro region using a projection lantern. During the screenings, relevant literary works were read out loud to accompany the films.

In the 1910s, cinema was considered more of a business than an art but it continued to captivate Sadovsky’s imagination. In 1912, Dmytro Hamaliy, a bandura player and film director, decided to film the popular theatrical play “Pan Shtukarevich”. He set up a glass pavilion near his theatre building on Troitska Square in Kyiv for this purpose. Mykola Sadovsky provided the funding for this initiative. In 1913, Sadovsky financially participated in Hamaliy’s next film called “Zaporizhian Treasure”. The film was based on a play by Kostiantyn Vanchenko-Pysanetsky and was shot in the suburbs of Kyiv. During the filming, an improvised Gypsy camp was set up in the forest.

It is possible that if the First World War hadn’t happened, Sadovsky’s involvement in cinema could have grown into something much more significant, like establishing his own film studio. However, the war led to a shift in film resources towards war chronicles, which halted the development of artistic cinematography.

Later, during the new cinematographic boom of 1918, when several private film studios opened in Kyiv and the film company Ukrainfilm started operating under the orders of Hetman Skoropadsky, Sadovsky was preoccupied with his own theatre and the creation of the National Opera, making it unlikely that he had enough time for cinema.

New Horizons in the Cinematic Career

In 1921, when he emigrated to Czechoslovakia, Mykola Sadovsky did not give up his dreams of pursuing a career in cinema. In fact, it was in this new country that the film industry was rapidly growing, with the Prague-based studio “AV” (later known as “Barrandov”) becoming one of the biggest and most influential studios in Europe. Upon arriving in Uzhhorod in Transcarpathia, Sadovsky took charge of the Ukrainian theatre of the “Prosvita” society. He starred in a full-length historical film titled “Koriyatovych” (“The Enchanting Ring of the Carpathians”).

This film was dedicated to the legendary Prince Fedir Koriyatovych and was one of the first Czech film productions. Although Sadosvky played only a small role, the film was a great success. Its premiere in Prague in November 1922 was attended by President Tomáš Masaryk, which gave Sadosvky confidence in his future in the film industry.

In the summer of 1923, Mykola Sadovsky left Uzhhorod and moved near Prague. He intended to organise a permanent Ukrainian theatre to direct films and act. Sadovsky even planned to adapt Spyrydon Cherkasenko’s historical play about Ivan Sirko, titled “What the Reed Was Whispering About…”. However, he failed to realise his grand cinematic plans in Prague; there are unconfirmed reports that he did plan to direct and act in a Czech film called “Golden Wolf,” which was released in July 1924. Feeling like a stranger in exile and, most importantly, realising that he was wasting valuable time for self-realisation in cinema, Sadovsky decided to return to Ukraine.

The Disappearing World on the Big Screen

Mykola Sadovsky arrived in the Bolshevik-governed Ukraine in the spring of 1926 and remarkably quickly adapted to the new Soviet conditions. In May of the same year, he joined the Kyiv Governorate Department of Arts Workers. He adopted all Soviet formalities, which allowed him to continue his creative work and fully integrate into the filmmaking process. Sadovsky returned to the theatrical stage immediately after his arrival and played a part in the “The Inspector General” play at the Ivan Franko Theatre.

Poster of “Vanka and the Avenger”. Source: vufku.org

Mykola Sadovsky joined the production of the new Ukrainian cinema in the summer of 1927, likely with the help of old acquaintances. He was invited by Axel Lundin, the once-popular Kyiv actor and 1920s film director, to play the role of the ‘Miller’ in the children’s adventure film “Vanka and the Avenger”. This film became the first film of the new Kyiv Film Factory. On the screen, Mykola Sadovsky portrayed the Miller, whose mill is accidentally discovered by the Bolshevik-minded boy named Ivas Klymenko and appears only at the film’s end. Despite having only a few episodes, Mykola Sadovsky’s performance stood out due to his voluminous, detailed existence in the frame, unlike most other performers who “performed” by excessively gesturing and staring.

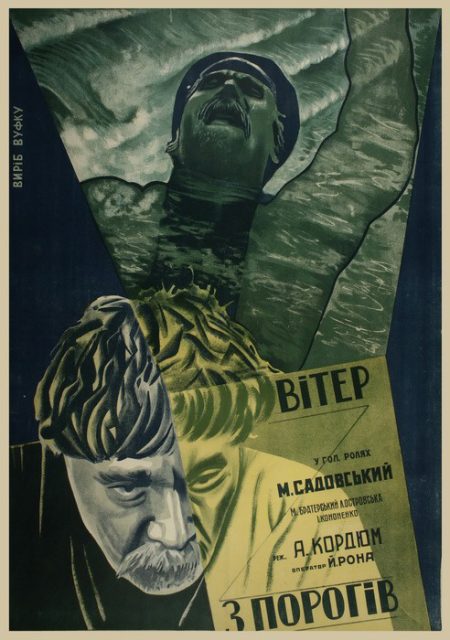

Mykola Sadovsky demonstrated a special depth of film acting, determined by the meaningful content of each individual dramatic situation in his final film role as an old lockmaster in the film “Wind Across the Rapids” (“The Last Lockmaster”). Andriy, a friend whom he knew from Katerynoslav and who was known then as Arnold Kordyum, invited Sadovsky to the main role in his avant-garde-styled film about the construction of the Dnipro Hydroelectric Station.

Poster of “Wind Across the Rapids”. Source: vufku.org

The film by Kordyum was one of the several art projects dedicated to the giant construction on the Dnipro, including “Dniproges” by Hlib Zatvornytsky (1927), “The Eleventh” by Dzyga Vertov (1928), “Stormy Nights” by Ivan Kavaleridze (1931), and “Ivan” by Oleksandr Dovzhenko (1932). However, “Wind Across the Rapids” stood out with its emphasis on the dramatic confrontation between the old patriarchal world of the Ukrainian village and the new aggressive Soviet industrialisation. This tragic clash was represented through the personal fate of the old lockmaster Ostap Kovban (played by Mykola Sadovsky), whose daughter, despite her father’s will, went to work on the construction while he went mad after an unsuccessful attempt to destroy the bridge foundation pit so that construction of the dam would stop.

There are numerous accounts about the risks of filming this movie, shot by the German cinematographer Joseph Rona; most of them relate to Mykola Sadovsky. These stories include Sadovsky’s encounter with his old acquaintance Dmytro Yavornytsky; his daring immersion into the turbulent waters of the Dnipro, passage on a raft through the largest rapid, Nenasytets, his genuine and interested communication with real lockmasters and peasants, as well as humorous anecdotes about trimming Sadovsky’s famous long moustache. As is often the case, over the years, these stories were embellished with additional details.

The movie “Wind Across the Rapids”. Source: vufku.org

In the domestic scenes, where the old man, Ostap Kovban, quarrels with his son, manages the household, prepares for his daughter’s wedding, and searches for her after her escape, Sadovsky’s acting charisma is the most evident. Just like on a stage, Sadovsky shows strong gestures and powerful gaze; he acts with plasticity—slowly turning as if reluctantly, then suddenly becoming unrestrained, fiery, and erupting in anger. Sadovsky played remarkably insightfully, so much so that his young partner Ivan Kononenko marvelled at the skill of the old actor, recalling the “casual movements, ironically narrowed eyes with great emotional tension; a rich voice”. In the final scenes, Sadovsky surveys the Dnipro steppe with a completely devastated gaze and, in despair, unable to stop the construction, he prays to the ancient stone idol.

According to one anecdote, Mykola Sadovsky went so over the top in the film’s industrialised spirit that its creators were forced to change the original title from “The Last Lockmaster” to the more abstract “Wind Across the Rapids”, releasing it in March 1930.

After the screenwriter of the film, Hordiy Brasyuk, was arrested, it never made it to the screen, confirming that the expected “destruction of the old world” in filmmaking was a painful reality not anticipated by propaganda cinema.

The poetic sentiment that emerged in “The Last Lockmaster” through Mykola Sadovsky’s powerful performance, as well as the artistic design by Vasyl Krychevsky, became a unique feature of Ukrainian avant-garde cinema. This set it apart from other universal cinematic experiments. Enriched with the poetry of deep attachment to the national and historical past and with images of native Ukrainian nature, the Ukrainian avant-garde cinema proved to be openly controversial when it came to solving ideological tasks. The old Ukrainian theatre played a significant role in this ‘injection’ of Ukrainianness into Soviet agitational film production.