April 10 marks the 160th anniversary of Olha Horuzhynska’s birth. In 1886, she married one of the titans of Ukrainian culture, Ivan Franko. Ivan Franko (1856–1916) was a Ukrainian author, scholar, journalist, and political activist who rose to prominence in the late 19th century. He is known for his dramas, lyric poetry, short stories, essays, and children’s verse, with his naturalistic novels depicting contemporary Galician society and his epic poems representing the pinnacle of his literary contributions. “He didn’t reach the heights of his glory without the support of his wife—a remarkably intelligent, kind, and gentle woman, capable of anything, always ensuring that ‘Franko was living well at home,'” recalled Antonina Trehubova, the elder sister of Franko’s wife.

For 16 years, the Franko family lived in various rented apartments until 1902, when they finally moved into their own house in the Sofiyivska district in Lviv. The street derived its name from the lush greenery surrounding Stryiskyi Park, linked to the local Saint Sophia Church. This house became the lifelong residence of the writer and his wife until their passing (Ivan Franko in 1916 and Olha on July 15, 1941). Here, their four children—Andrii, Taras, Petro, and Anna—grew up. Today, the Lviv National Literary-Memorial Museum of Ivan Franko, also known as the Franko House, resides in this villa. The museum’s collections hold numerous items that the inhabitants of this home once cherished.

***

The house on Sofiyivska Street – the family villa

Not widely known is that the Franko family house was modelled after the wooden house in Kyiv belonging to the esteemed historian and Kyiv University professor Volodymyr Antonovych. Olha Franko held great reverence for Antonovych throughout her life. He was a lecturer at the Higher Women’s Courses, where Olha Horuzhynska studied. His house in Kyiv served as a hub of Ukrainian life, hosting gatherings of the Stara Hromada (‘Old Community’) and private lectures frequented, it seems, by Olha as a student.

Perhaps, living in Galicia, Olha sought to recreate the vibrant cultural atmosphere of her youth spent in the Antonovychs’ home. Maybe she envisioned her house as a cultural center, akin to the residence of Kyiv’s Old Community leader during her studies. Both reasons might have influenced her decision. Regardless, the Franko townhouse bears a striking resemblance to the Antonovychs’ home. Similar to Antonobych’s residence, the Franko house boasted a lush fruit garden. Here, Olha Franko created her delightful jams, jellies, and tinctures from the garden’s bounty. The Franko family also kept a variety of livestock, including chickens, rabbits, a cat, and dogs.

Photo: The Franko family villa

Funding for the construction of the Franko family home came from the writer’s jubilee gift, the sale of valuable items from Olha Franko’s dowry, and a long-term loan of 12,000 crowns (half the total construction cost) from the Regional Bank of Galicia at 4% interest. Their son Taras fully repaid the loan for the house in 1922. By 1940, the Franko villa had transformed into a museum, with Olha’s younger son Petro Franko serving as its inaugural director.

Photos and Wedding Gifts

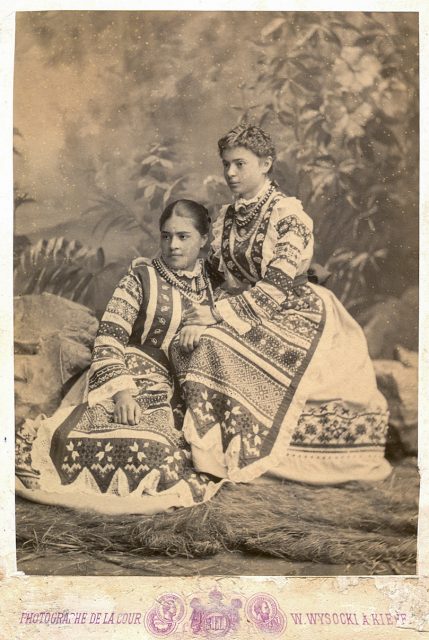

Preserved in the Franko family album are cherished photos of Olha Franko in various roles. One photo captures a young Olha alongside her elder sister Oleksandra, portraying her as a student at the Kyiv Higher Women’s Courses, elegantly attired in fashionable urban costumes typical of the era. Taken around 1885, this snapshot was captured at the renowned Kyiv studio of Polish photographer and poet Wlodzimierz Wisocki.

Photo: Olha Franko alongside her elder sister Oleksandra

In the same studio, the iconic portrait of Ivan and Olha Franko was taken on their wedding day, May 4, 1886. Their ceremony took place at the church of the Pavlo Galagan Collegium in Kyiv (now known as Bohdana Khmelnytskoho Street, 11). Witnesses included Hnat Zhytetskyi and student Krachkovskyi from the bride’s side and Stanislav Kyrychynskyi and Volodymyr Ihnatovych from the groom’s side. Priest Symeon Trehubov officiated the marriage. The wedding toasts highlighted the unity of Ukraine, celebrating the union of Austro-Hungarian citizen Ivan Franko with Russian Empire subject, Olha Khoruzhynska. This marriage symbolised unity in Kyiv, reflecting the political aspirations of the Old Community members for unity with the Galicians. Following the ceremony, Olha and Ivan departed for Lviv, captured in a photo wearing their travel attire. This portrait, styled after the French photographer Nadar, features top lighting and a monochrome background, focusing solely on the couple.

Photo: Ivan and Olha Franko on the day of their wedding, 1886

A cherished keepsake from that special day is the silver spoon Olha Khoruzhynska gifted to her groom on their wedding day. The front of the spoon bears the engraved initials “I. F.,” while the reverse side displays the date “4.V.1886.” Passed down to the museum by Ivan and Olha Franko’s daughter, Anna Klyuchko, during her second visit to Ukraine in November 1971, this spoon was a constant companion in Ivan Franko’s life.

Photo: The silver spoon Olha Khoruzhynska gifted to her groom on their wedding day

The only photo capturing the entire Franko family together shows them gathered on the steps of their newly built villa. In the centre are Ivan and Olha Franko, surrounded by their four children: Petro, Taras, Anna, and Andriy, from left to right. They appear seated, with open doors behind them leading to the kitchen and a view of the garden ahead. Despite the slightly blurry and fuzzy original image, we can still make out Ivan Franko in an embroidered shirt, Olha in a dark dress befitting the matriarch, and the sons dressed in the uniform of the Imperial-Royal Academic Gymnasium in Lviv. Anna stands out in light attire, with a braid styled like his mother’s on his head. This family portrait, captured between September 5 and 15, 1904, is credited to the ethnographer Pavlo Riabkov.

In August-September 1904, an ethnographic-anthropological expedition to Ukraine’s historic Boykivshchyna region was organised by the Shevchenko Scientific Society in Lviv, with funding from the Austrian Ethnographic Society in Vienna. Ivan Franko, along with Fedir Vovk, Zenon Kuzelia, and Pavlo Riabkov, took part in this expedition. Riabkov, known for his photographic skills, joined the group specifically as a photographer.

Photo: The Franko Family

Olha Franko’s embroidered shirts

Ivan Franko was known for his collection of embroidered shirts, which he wore both casually and on special occasions. After their marriage, Olha Franko took on the task of caring for these cherished garments and showed her own love for folk attire. According to Taras Franko, their mother often embraced folk clothing, often adding a headscarf for a touch of simplicity. Following her travels to the Hutsul region, she frequently wore Hutsul embroidered shirts paired with traditional caps.

Photo: The embroidered shirt for Olha Franko’s daughter.

Olha Franko was passionate about folk crafts and embroidery, often creating her own pieces. Anna fondly remembered an “embroidered napkin of my mother’s work” displayed at home. Today, visitors can admire Olha Franko’s handiwork at the Ivan Franko Literary-Memorial Museum in Lviv. On display are two towels featuring an eastern Ukrainian pattern, meticulously embroidered with red and black threads, along with her embroidered headscarf and a charming children’s shirt.

The children’s shirt holds a special significance: Olha Franko lovingly stitched it with red, black, and sometimes green threads in a cross-stitch pattern for her daughter Anna. Later, Anna Klyuchko passed down this cherished shirt to her own sons, Taras and Myron (Olha Franko’s grandsons), before it found its place in the museum’s collections. Inspired by her mother’s talent, Anna Kluchko also took up embroidery. Visitors of her apartment in Vienna remarked on its beauty, likening it to a beautifully painted Easter egg with its array of embroideries and floral decorations.

Photo: An embroidered shirt.

Memoirs: “Episodes of My Life”

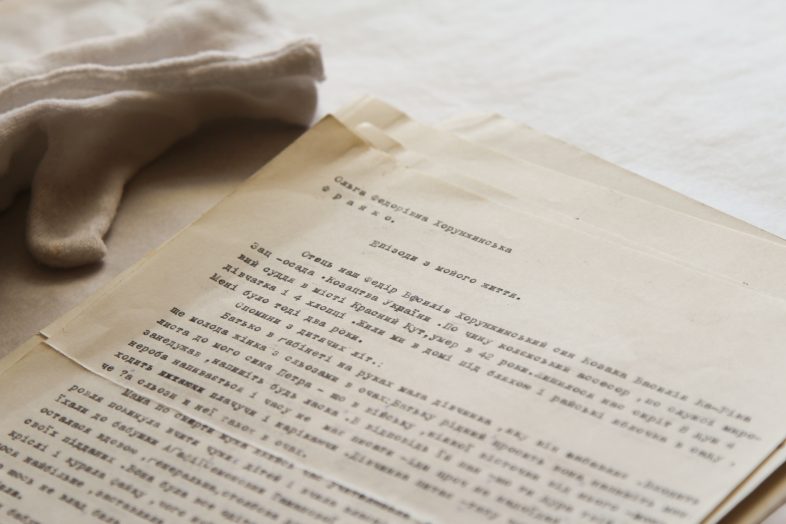

The idea of penning her life story first occurred to Olha Franko back in 1893. In a letter to her husband, who was then immersed in his doctoral dissertation in Vienna, she expressed, “To make it easier to die, I think of writing my life.” In this same letter, Olha outlined the main chapters of her life: her early years in the village of Tymofiivtsi until age 9, followed by eight years of education at the Kharkiv Institute for Noble Maidens, then her time in Kyiv at the Higher Women’s Courses, and finally, the move to Galicia. However, she didn’t act on this idea then. It was only after her husband’s death in 1926 that Olha Franko revisited this notion.

In 1926, Olha Franko sent the manuscript of her memoirs to her daughter Anna in the village of Dovhe in Transcarpathia. From Anna’s letter to her mother dated May 20, 1926, we learn that these memoirs consisted of two parts: “Your memoir, the first and the second, I received, reread, and kept as a keepsake.” It seems Anna drew from this “memoir” while writing her own memories “Ivan Franko and His Family” (Toronto, 1956).

During her visit to Ukraine from Canada in November 1971, Anna pledged to donate these memoirs to the Ivan Franko Museum in Lviv. On January 27, 1972, she sent a typewritten copy of her mother Olha Franko’s memoirs, having reprinted them using a printing machine. However, this was just the initial part of Olha Franko’s memoirs titled “Episodes of My Life.” The full manuscript, along with the second part, remained in Anna Franko-Klyuchko’s personal archive. Their current location remains unknown.

Today, at the Ivan Franko Museum in Lviv, there remains a treasured letter from Anna alongside a typewritten copy of the first segment of Ivan Franko’s wife’s memoirs. This invaluable document sheds light on lesser-known facets of Olha Khoruzhinska’s life, particularly her childhood and education at the Institute for Noble Maidens in Kharkiv. Hopefully, the original memoirs will one day grace the collection of the Franko House, enriching our understanding of this remarkable woman’s life.

Photo: Olha Franko’s “Episodes of My Life”

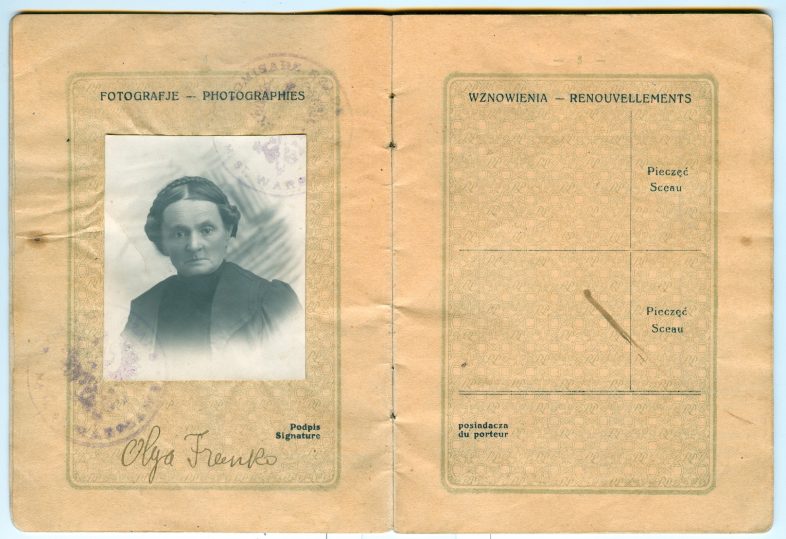

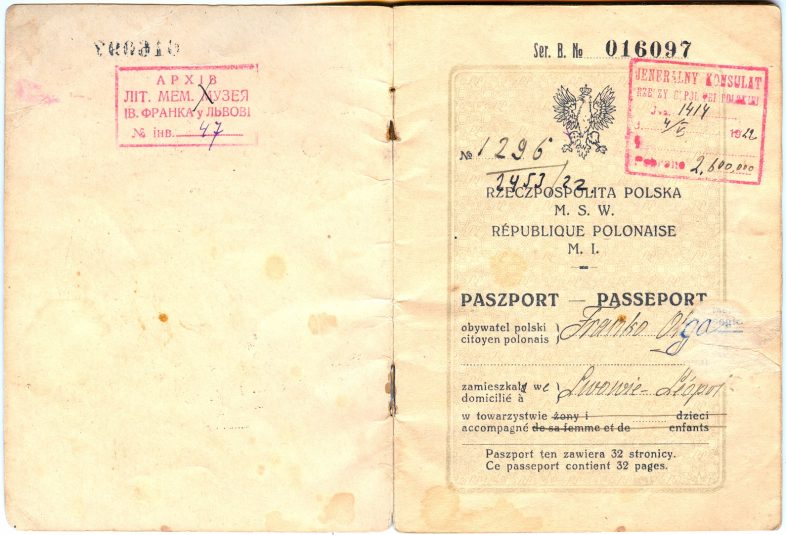

Olha Franko’s Passport

Olha Franko’s passport, which was issued to her in Polish for travel to Soviet Ukraine in 1922 (series B No. 016097), consists of 32 pages. The document states Olha Franko’s birth in 1863 in Kyiv (though, in reality, she was born in 1864 in the village of Bіrky in the Poltava region) and lists her as a resident of Lviv. It includes a description of her appearance: average height, oval face, dark hair, and brown eyes. The passport features a photograph of Olha Franko, who is in dark attire with a sombre expression and is at the age of 58.

Photo: Olha Franko’s passport.

Valid until August 11, 1922, the passport bears visas from the Polish embassy in Kharkiv and the Soviet embassy in Poland, as well as the Soviet embassy in Kharkiv for return to Poland. According to these visas, Olha Franko was permitted to travel to the Ukrainian SSR via the Zdolbuniv-Shepetivka border crossing and return home (which was the territory of Poland at the time) through the border crossing point Kryvin (a station in the village of Staryi Kryvin, Khmelnytskyi region, on the Shepetivka-Zdolbuniv line). We know that Olha Franko used this passport for her journey to Kharkiv in May 1922, where her elder son, Taras Franko, was residing.

Following the defeat of the national liberation movement, Taras Franko found himself in the Kozhukhiv suburban concentration camp, from which he was released in August 1920 and sent to work in Kharkiv. As a mother, Olha Franko was determined to have her son return home, and she pursued various avenues to make this happen. Eventually, obtaining permission to leave from the State Political Directorate (GPU), Taras Franko finally returned to Lviv at the start of July.

Photo: Olha Franko’s passport.

Olha Franko’s hand fans

Olha Khoruzhinska’s background, education, and milieu undoubtedly shaped her preferences in attire and accessories.

During her time at the Kharkiv Institute for Noble Maidens, Olha adhered to the typical dress code of the era. The institute uniforms were modest, with a closed, dark, strict silhouette complemented by crisp white collars, cuffs, and occasionally aprons. Adding to the ensembles were the customary headgear, jewellery, chatelaines, gloves, and fans, among other items.

In the early 1980s, the Ivan Franko Museum in Lviv acquired a set of valuable artefacts from Olha Franko’s daughter-in-law from Bilevychi, Olha Franko. Among these treasures were two fans belonging to Franko’s wife, Olha Khoruzhinska. These exceptionally precious pieces have an intriguing, almost detective-like history.

Photo: Olha Franko’s hand fans

The first fan, black in colour and labelled in museum records as “theatrical,” is crafted on plates of black wood. Its screen is made of gas fabric adorned with delicate silk white ribbons running through it. The thicker side plates of the fan, known as guards, as well as the inner plates, are embellished with a golden floral motif. This fan also features a decorative tassel and a ring, allowing it to be attached to a belt or chatelaine.

The second fan is a masterpiece in itself. Its foundation consists of plates made from tortoiseshell, while the screen is crafted from paper, mimicking parchment and being hand-painted. On the front of the fan, we see a hunting scene from the village of Hovory, now part of Khmelnytskyi Oblast. In the background, the panorama includes the village and the preserved palace of the Stadnitski-Tyszkiewicz family. The reverse of the screen showcases two family coats of arms – Sherniava and Leliwa, belonging to the Stadnytskyi and Tyszkiewicz families, respectively.

Olha Franko’s armchairs

According to Anna Klyuchko’s memoirs, their room in the family home was the most luxuriously furnished. Among the belongings Olha Khoruzhinska brought with her were mentions of furniture “brought from Kyiv, several paintings, carpets.” Unfortunately, over time, most of these items were lost. The silverware for 24 people, Olha’s dresses, and “furs” — all of these exist now only in memory. However, some pieces of the furniture set were not just preserved but are now recognisable and seamlessly integrated into the rooms that Franko’s wife used in her lifetime.

Photo: Olha Franko’s armchairs.

Following Ivan Franko’s passing, certain pieces of furniture directly linked to the writer’s life were acquired by the Shevchenko Scientific Society in Lviv (desk, library cabinet, armchair, tables, sofa, etc.). The furniture from the women’s rooms naturally passed on to the Franko family’s sons — Petro (like a coat rack from the hallway, a set of two chairs and a sofa, upholstered in cherry-coloured velvet with a floral pattern) and Taras (a chest of drawers). The Franko Museum acquired these pieces, and today, they not only form part of the memorial collection but also serve as a genuine highlight of the exhibition at the Franko family villa.