While all eyes in Ukraine were on the presidential election followed by the parliamentary campaign, Q2’19 saw the fastest economic growth for the past seven years, with GDP growing 4.6% compared to Q2’18. This final note nicely summarized Ukraine’s development in the five-year post-revolutionary wartime period from 2014 to 2019 as economic indicators outside of territories occupied by Russia have moved past 2013 levels.

According to the Derzhstat, the state statistics bureau, although 2018 GDP was 8.7% below 2013 GDP in Ukraine – excluding occupied Crimea – gross regional product (GRP) in Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts plummeted 62.1% over those same five years. This was mainly the result of the loss of territory, not because of a steep economic decline in the areas not occupied by Russia, as The Ukrainian Week has reported in the past. However, lack of accurate statistics on the dynamics in the non-occupied areas of the two frontline oblasts means that both oblasts need to be completely excluded from estimates. Whereas in 2013, Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts accounted for over 15% of Ukraine’s GDP less Crimea, in 2018, GDP for the rest of the country was 0.7% higher than in 2013, ignoring the noted loss of GRP in these two oblasts. Since Ukraine’s population shrank by 1.6%, 2018 per capita GDP was 2.3% above the 2013 indicator, leaving out Crimea and frontline Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts. With 3.7% GDP growth posted in H1’19, it looks like GDP growth will be 4-4.5% higher than in 2013 even without adjusting for population change, and 6-6.5% higher on a per capita basis.

Leaders and outsiders

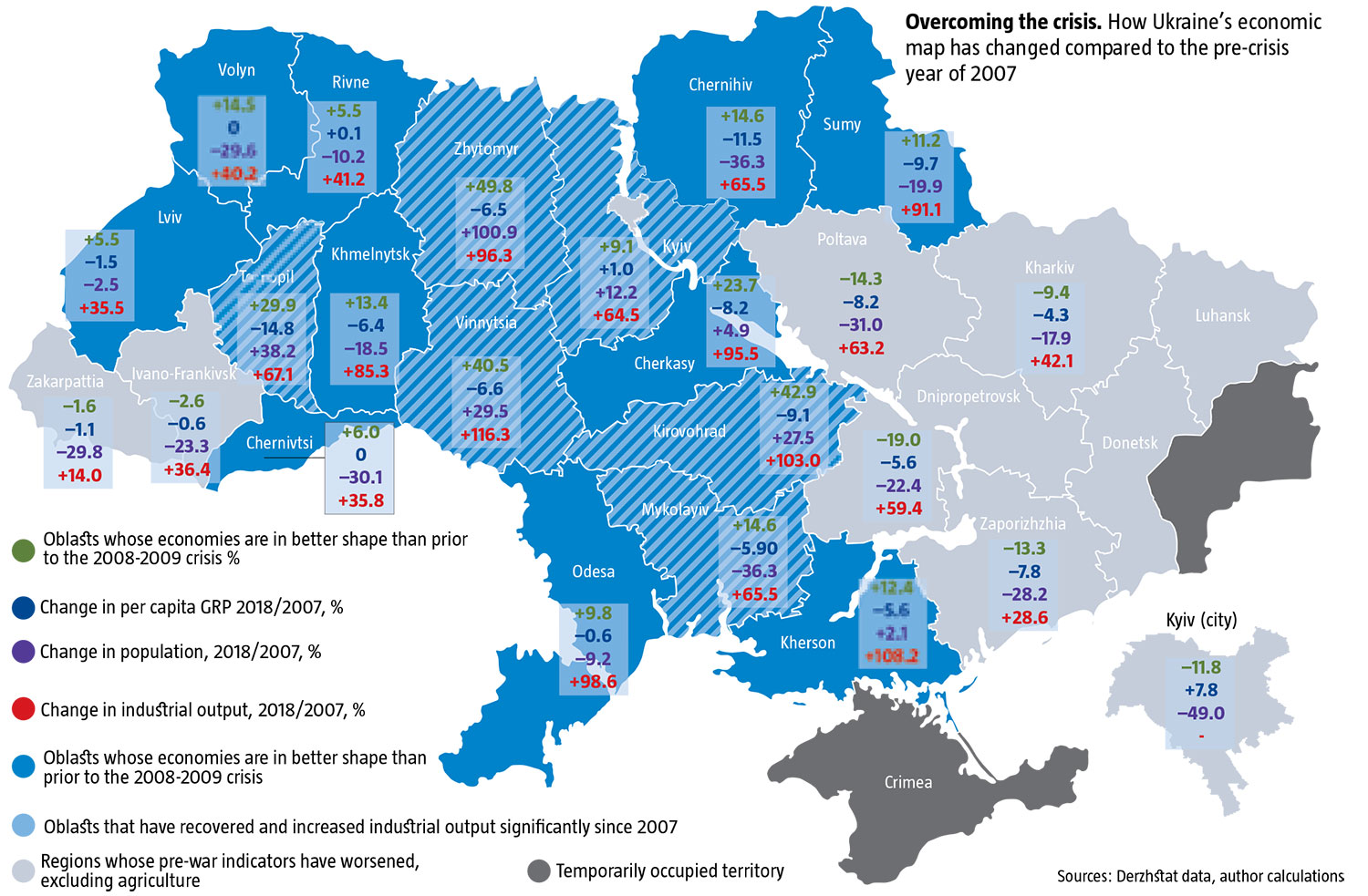

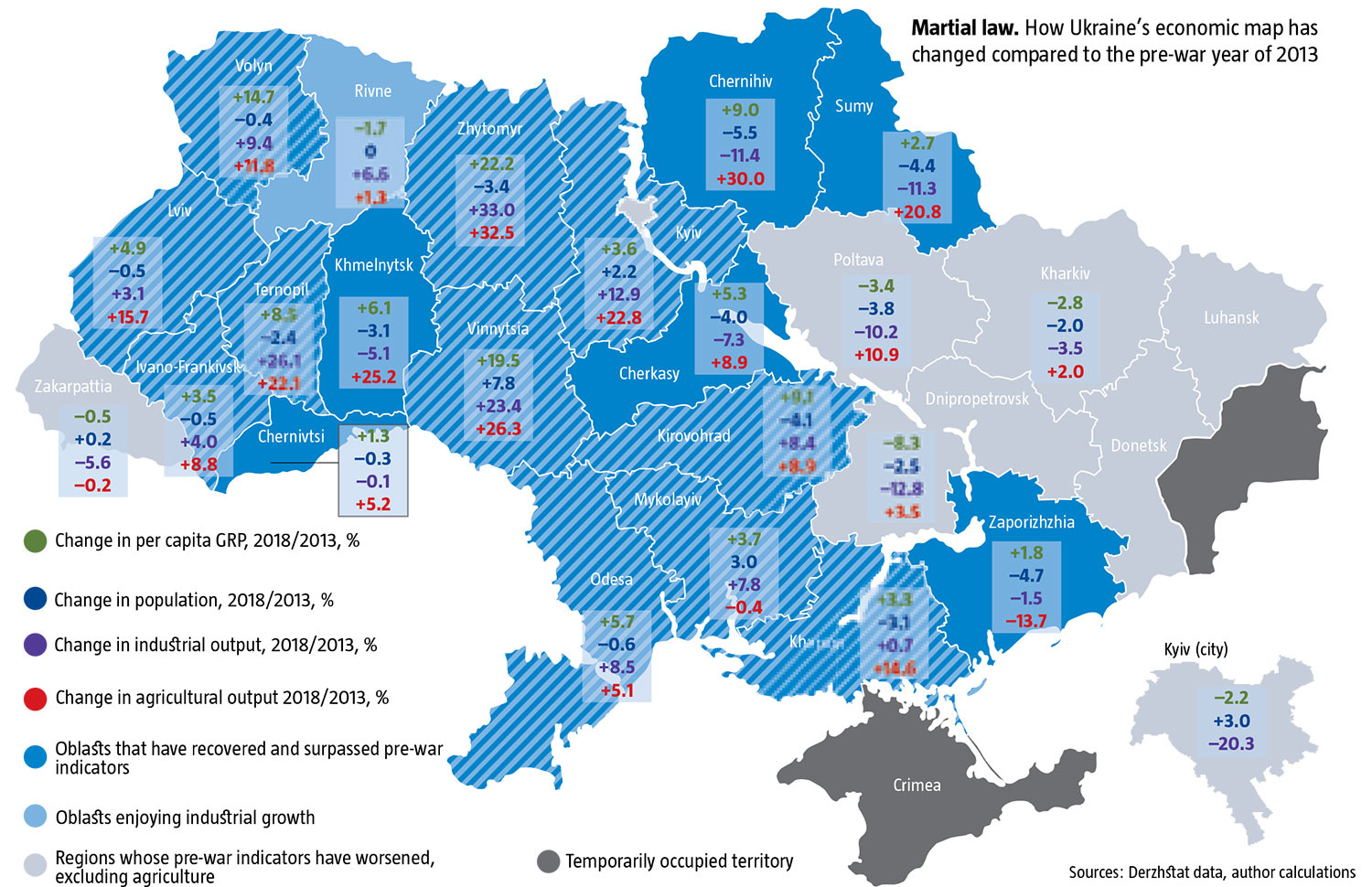

While the economy and key sectors have already passed pre-war indicators in non-occupied Ukraine, individual oblasts are going through a real economic revolution. Some are in a much better shape economically than in 2013, while former economic leaders still have not recovered to pre-war levels. The trends of the past five years partly match the long-term trends that emerged in Ukraine during the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, whose consequences most regions still are a long way from recovery, in contrast to the decline in 2014-2015 provoked by Russia’s aggression. Two features in Ukraine’s economic picture that could be seen both before and after Russia’s aggression began are a lag or stagnation in southeastern oblasts and farm sector growth that outpaced the industrial sector (see Overcoming the crisis).

In 2018, 16 out of 25 oblasts posted better results than in 2007, with per capita GRP 24-50% up in five of them. This economic growth belt spans Zhytomyr with +49.8%, Kirovohrad +42.9%, Vinnytsia +40.5% and Cherkasy +23.7%, and Ternopil with +29.9%. Sandwiched between them, Khmelnytskiy Oblast is the odd man out, up only +13.4% compared to 2007, but still posting significant growth. The group of oblasts with economic indicators up 9-17% since 2007 includes eight more that are adjacent to the core growth belt from the south, southeast and west: Odesa, Kherson, Mykolayiv, Kyiv, Chernihiv, Sumy and Volyn Oblasts. GRP in Lviv, Rivne and Chernivtsi Oblasts is up only 5.5-6% since 2007.

Ivano-Frankivsk and Zakarpattia Oblasts are only on the verge of recovering to 2007 levels, posting –2.6% and 1.6% and should beat their 2007 indicators this year if this year’s trends hold. Meanwhile, Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhzia Oblasts, the ones directly adjacent to the conflict zone, remain far from pre 2008 crisis peaks, as does the neighboring Poltava Oblast. All three are 10-20% behind 2007 levels and will have a hard time catching up any time soon: most of them are still struggling to recover to 2013 levels. Kharkiv and Poltava oblasts are still 2.8-3.4% behind, while Dnipro Oblast remains down 8.3%. Zaporizhzhia Oblast is the only one in this depressed group that has managed to improve its indicators by a symbolic 1.8%. The rest of Ukraine’s oblasts have seen per capita GRP improve strongly in 2018 compared to 2013. Given overall growth by 3.7% in H1’19, even Kyiv (–2.2%), Rivne (–1.7%) and Zakarpattia (–0.5%) oblasts are probably on the way to recovery to pre-war figures.

RELATED ARTICLE: Clouds in a silver lining

The economic dynamics of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts have to be analyzed separately, as most of their one-time economic potential is now under Russian occupation. On one hand, the available statistics show a deep decline in these oblasts compared to 2013, let alone 2007. On the other, this steep decline was primarily caused by the loss of control over territory. As The Ukrainian Week has written before, based on fragmentary economic data from Ukraine-controlled parts of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts and their major urban areas, the real economic decline there is definitely not as deep as official data from Derzhstat suggests, and some parts are also recovering or improving compared to 2013 or 2007.

At the same time, talking about positive dynamics in some oblasts and depression in others is precisely about their dynamic, not their current level of development. Faster development in the growth belt centered on Right Bank Ukraine does not mean that these oblast economies are wealthier or more advanced now. What they are mostly doing is catching up with the oblasts that were more successful in the past. The oblasts whose economies have been in decline since 2008 are often still far more developed than most of those that are growing rapidly now.

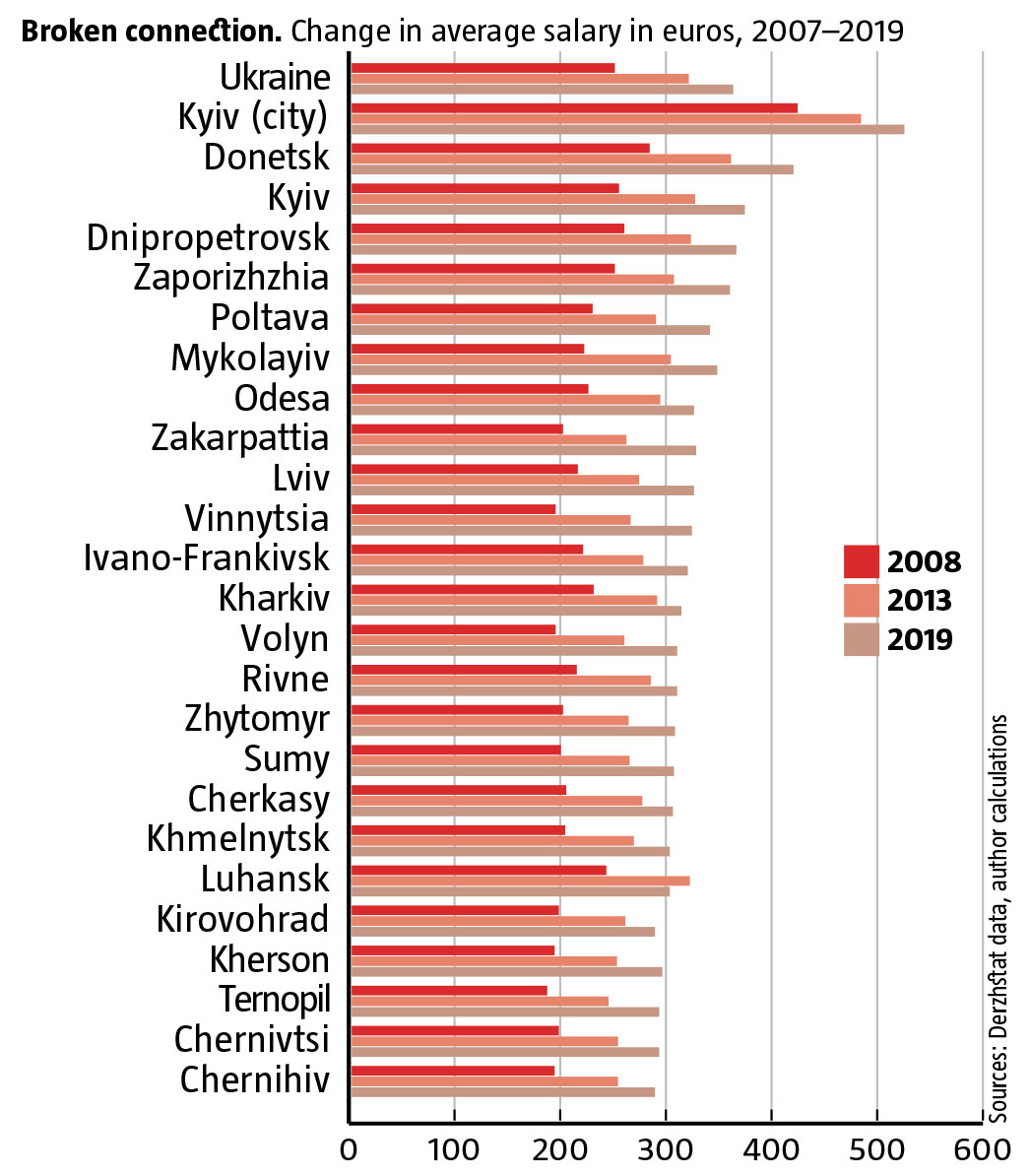

Moreover, the change in average salaries across oblasts in the past three years does not always match other economic indicators (see Broken connection). The average salary in those oblasts with serious economic growth over 2016-2019 is now lower than before. In others, where the economy is worse compared to 2016, the average salary is the sane or higher than three years ago.

Among other things, this leaves open the question of how fairly the benefits of stronger economic growth are distributed in these oblasts. Just like in the 2000s, distribution is very uneven in the southeast. A large share of profit leaks out of individual oblasts and out of the country altogether through transfer pricing. Moreover, the oblasts with the fastest economic growth have some of the lowest official employment rates, their local budgets and social funds are poorly funded, infrastructure continues to fall apart, and many of their residents have been looking to find a better life elsewhere.

New trends

Over the past five years, regional economic trends are increasingly different from those that were observed after the 2008-2009 crisis. Economic recovery, especially in the growth belt, is tied to unusually dynamic growth in Ukraine’s EU neighbors, which are growing is more intensely than Ukraine or even its most successful oblasts.

For instance, Volyn and Chernihiv Oblasts have joined the top five economic leaders, although they’ve never been in that league before. Khmelnytskiy and Lviv Oblasts have seriously improved their economic position after lagging behind prior to 2013 and struggling to recover to pre-crisis 2007 levels. Interestingly, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast joined the growth belt too, although it was struggling to recover from the 2008-2009 crisis in the previous five-year period. Kyiv, Odesa and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts have far better economic dynamics now, compared to pre-2013, while Ternopil and Cherkasy Oblasts have slipped lower. Kirovohrad Oblast has declined compared to pre-war 2013, ranking fourth with economic growth of +9.1%. Even Kharkiv and Poltava Oblasts are among the leading oblasts, although they have not caught up with 2013 levels. But these quibbles seem insignificant compared to the deep crash of 2008-2009, from which they had not recovered by the previous economic peak in 2013 – and still haven’t.

Interestingly, the epicenter of the growth belt has been shifting north in recent years and, to a lesser extent, west. By contrast, Cherkasy and Kirovohrad Oblasts have been really lost position. This is even more astonishing given the fact that economic growth per capita in these central oblasts has had a serious boost as their populations shrink rapidly. A comparison of populations in different oblasts between 2007 and 2018, and between 2013 and 2018 shows how important, sometimes critical, this factor is for the recovery and growth of per capita GRP. In the city of Kyiv, for example, per capita GRP has been lower for both 2007-2018, and 2013-2018, as the pace of economic growth has been slower than population growth.

Still, regional economic dynamics should not be compared without taking into account population change. The latter determines employment in key sectors and the number of consumers generating income. In most central oblasts, the population has been shrinking faster than in western Ukraine, where it has barely changed over a long period, metropolitan Kyiv, where the population continues to grow steadily, and even some oblasts in southeastern Ukraine.

Farming or manufacturing?

Ever since the global economic crisis of 2008-2009, agriculture has been the main driver of Ukraine’s economy overall and of most of its oblasts. More recently, however, several agricultural drivers of the past in southern and eastern Ukraine have slowed down. Mykolayiv, Kherson, Kirovohrad and Odesa Oblasts saw the highest increase in agricultural output – up 99-128% – between 2007 and 2018, while growth on the Right Bank central and western oblasts was severalfold slower after 2007. Since 2013, however, the situation has been radically different.

The epicenter of both industrial and agricultural growth is increasingly shifting to the Right Bank, with further offshoots towards the west and northeast. Zhytomyr, Vinnytsia, Khmelnytskiy, Chernihiv, Kyiv, and Ternopil Oblasts have taken over leadership in agricultural growth. Dynamics in Lviv, Volyn and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts have improved significantly compared to the one-time leaders in the southern steppe, such as Odesa, Dnipro and Kharkiv Oblasts. In Mykolayiv and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts, agricultural production is in a worse state than it was in 2013 (see Martial law). Overall, agricultural growth is not much faster than industrial growth, especially in successful oblasts. Meanwhile, industry has been showing better recovery and growth than in the previous five years. 2008-2015 were the years of shrinking, sometimes tumbling industrial output, interrupted by a brief spurt of growth in 2010-2011. As a result, industrial output was at 66.6% of 2007 levels in 2015, according to Derzhstat.

Most regions have not yet recovered from the deep crisis that hit Ukraine’s industry after 2008. In fact, just six oblasts saw better industrial results in 2018 than in 2007, and these were the ones with relatively small output to begin with. Zhytomyr Oblast saw the highest growth, +100.9%, mostly thanks to a boom in extraction and mining. Industrial sectors in Vinnytsia, Kirovohrad and Ternopil Oblasts grew a modest 27-38%, while industrial output grew just 12.2% in Kyiv Oblast and a paltry 2.1% in Mykolayiv Oblast. These are mostly regions from the economic growth belt and this trend has been growing stronger. The seven leaders of industrial growth in 2013-2018 include Zhytomyr, Ternopil, Vinnytsia, Kyiv, Volyn, Odesa, and Kirovohrad Oblasts. Mykolayiv, Rivne, Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv and Kherson Oblasts trail them with somewhat slower growth. But half of Ukraine’s oblasts, including the southeastern industrial giants that account for the lion’s share of output and employment, are far behind both 2013 and 2007 levels. These include Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, down 12.8% compared to 2013 and down 22.4% compared to 2007; Poltava Oblast, down 10.2% and 31%; Kharkiv Oblast, down 3.5% 17.9%; and Zaporizhzhia Oblast, down 1.5% and 28.2%. Kyiv is no exception, even if it remains the largest industrial hub in Central Ukraine: industrial output in 2018 was 20% lower than in 2013, and barely half of 2007 levels.

The striking gap between 2018 and 2013 or 2007 shows that Ukraine’s industrial sector was hit very hard by the 2008-2009 crisis, not by Russia’s aggression or crumbling economic relations with Russia since 2013, and is still struggling to recover. The best evidence of this are industrial powerhouses like Zaporizhzhia and Kharkiv Oblasts, where output has almost recovered to 2013 levels, but is still far behind 2007.

At the crest of a wave?

The comparison of data from different oblasts at the peaks of previous economic waves followed by steep declines is deliberate. Global economic trends and vaster imbalances in Ukraine’s domestic economy increasingly suggest that it is now close to yet another peak of growth that could well be followed by a painful decline in the not-too-distant future. Another cyclical crisis appears to be looming in the global economy, and it will once again hit Ukraine’s economy, which is excessively dependent on the international situation and still very poorly diversified.

RELATED ARTICLE: Stop the vicious cycle

The situation will be worse if this cyclical decline comes hand-in-hand with the new government’s inability to offset the negative effects of the looming economic troubles and its inability to implement policies to encourage accelerated economic growth down the line. If this happens, Ukraine risks finding itself in a downward spiral where every new boom-and-bust cycle leaves the economy in a worse position. Despite periods of relatively dynamic growth in 2000-2007, 2010-2012, and 2016-2019, real GDP remains 1.5 times below the level in 1990. Moreover, Ukraine continues to lag far behind its more successful EU neighbors: where Ukraine’s economy grew 3%, Poland, Hungary and Romania grew 4-5%. Indeed, their economies are now 25-30% bigger than in 2013, whereas Ukraine’s economy has expanded just 4-6%.

In the end, it won’t be enough for Ukraine to recover to 2013 levels from 2013 or even the far higher indicators of 2008 or 1991. If it wants to break through from the developing world and become a developed European state, the country needs to pull out of the downward spiral, where every economic cycle leaves it worse off than before. This means long-term double-digit growth, and that will only be possible with profound changes in Ukraine’s economic policies.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook