The US dollar is finally down to UAH 25 for the first time in the last three years, but reactions to this new exchange rate vary. Those earning their income in hryvnia are happy. They can now afford a new computer, washing machine or vacation abroad with their hryvnia-denominated salaries. Those who have been hiding their dollars in their mattresses are kicking themselves, fearful of that the greenback will weaken even further. In remote villages in southern Ukraine, rumors circulate that the buck will go down to UAH 10 – the Big Mac index says that’s where it should be – so it’s time to sell dollars off ASAP. Supposedly, they say, the new Government will sort things out and all the economic troubles of recent years will vanish. People there are on the verge of panic: the crazy election euphoria has not yet dissipated, which is pushing them to act irrationally in a perfectly rational sphere. The cheaper dollar has stirred up the whole country. In fact, if the current situation in the forex market continues, Ukraine’s economy is likely to face hard times.

Only the lazy Ukrainian has not heard about why the hryvnia is growing stronger: the revaluation is largely thanks to a good harvest last year and a serious inflow of foreign hot money captured by government bonds. However, few have been talking about the consequences, and these will be both far-reaching and mostly bad. Of course, people like to see their purchasing power in hryvnia rise when measured against imported goods. But this is not a balanced situation, so it cannot benefit the economy long-term for three main reasons.

Imbalance of trade

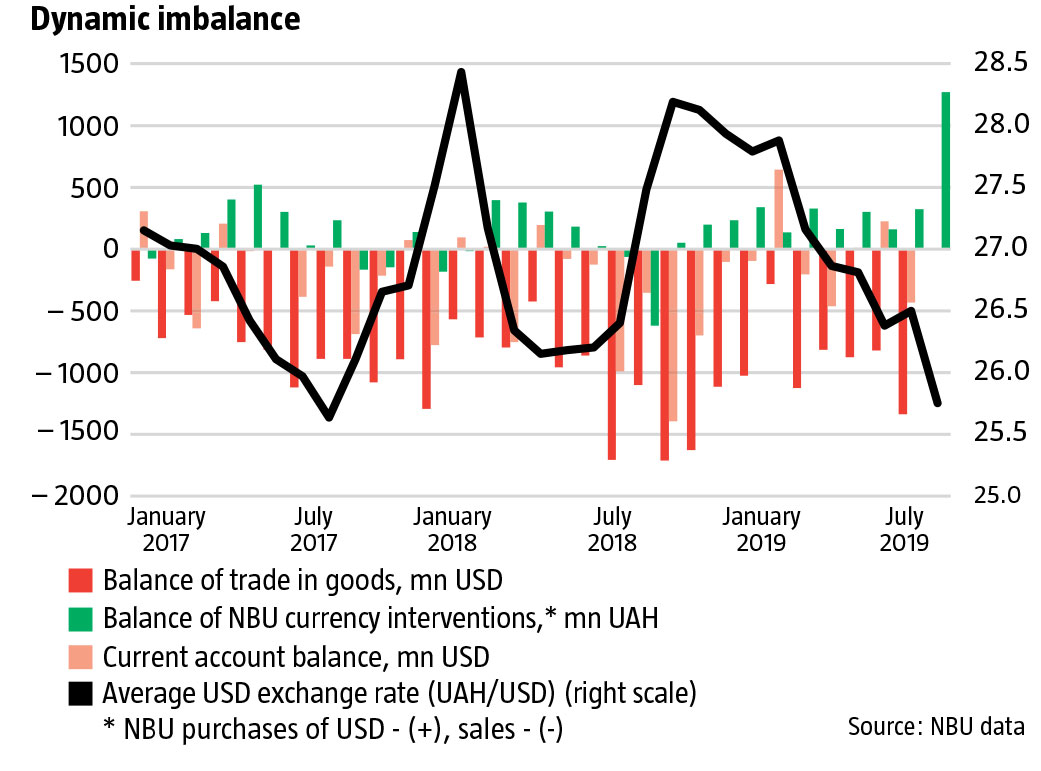

A cheaper dollar seriously undermines Ukraine’s balance of trade as the gap between export revenues and spending on imported goods widens sharply. According to the National Bank of Ukraine, the trade deficit in June was over $1.3bn, up 55% from last year. The current account deficit was $432mn, up 250% from what it was in June 2018 (see Dynamic imbalance).

Why does this matter? Investors see the current account balance and trade balance, its key component, as fundamental value indicators for a country’s currency. The greater the deficit, the higher the risk of devaluation. Non-residents have pumped billions of dollars into Ukraine’s government bonds in recent months because the hryvnia was cheap and interest rates were high. Interest rates have already started going down following the NBU’s prime rate, and the central bank has signaled that this trend will continue.

Meanwhile, the hryvnia is no longer cheap. Quite the contrary, it is fairly expensive now, measured against Ukraine’s balance of payments. This means that government bonds are starting to lose their appeal in the eyes of non-resident investors, day by day. As a result, the hot money inflow risks turning into an abrupt outflow. Ukraine’s forex market is like a spring that is being increasingly tightened by foreign capital. The tighter it is turned, the less the spring is able to withstand continuing pressure. As soon as the pressure lets up, the spring will shoot off, causing untold harm.

A comparison between the current situation and the pre-financial crisis years does not inspire optimism. Ukraine’s trade deficit sucked $1.3-1.5bn out of the economy every month in late 2007 and early 2008. The balance of revenues and trade in services were not as favorable then as they are now, so the total current account balance was far worse. But who can state with certainty what the current account balance might be if the dollar goes below UAH 25? Ukraine’s current account may well approach the level of 12 years ago in unfavorable conditions, such as shrinking global prices for raw materials, steep growth in consumer lending in Ukraine, a poor harvest, and so on.

RELATED ARTICLE: Persuasive economy vs uncertain policy

The situation was far worse in 2013. The trade deficit in goods was over $2bn some months, once even going above $3bn. Extreme austerity, mobilizing resources and the Yanukovych credit from Russia were the only things that saved Ukraine from a crash. Now, Ukraine is in a market environment and non-residents are in a position to take investment decisions that will hurt the country, even with far better indicators. Should things get to that point?

Melting profits

Lower earnings for domestic manufacturers are another downside to the cheaper dollar. Exports of goods and services accounted for over 45% of Ukraine’s GDP in 2018, which means that exporters accounted for almost half of the economy. They are now having a hard time as the stronger hryvnia hits their bottom line. The US dollar is almost 8% cheaper now than the average last year, and the gap is still larger compared to the rate used in the 2019 Budget. This means that exporters have earned around 10% less this year.

Meanwhile, their costs are growing: the average salary in June 2019 was almost 18% higher than in 2018. Stuck between a rock of revenues and a hard place of spending, Ukrainian exporters are watching their profits melt away like the last snow in the March sun. At this rate, Ukrainian entrepreneurs could soon find themselves unable to make ends meet cash-wise, let alone invest – the perfect recipe for an economic downturn.

Life is easier for big businesses, as they can keep foreign currency earnings in accounts abroad until the dollar rises again. Full currency liberalization will allow this now, whereas just a few months ago exporters were forced by law to sell a share of their revenues on the interbank forex market. Meanwhile, SMEs are getting desperate. Farmers are delivering their 2019 grain harvest to elevators, they’re getting paid in hryvnia, and they’re struggling to understand what they should do with such low relative earnings and how to start the next sowing season.

The situation in the real sector is very similar to spring 2008, when the dollar went down to UAH 4.65 from UAH 5.05, a rate supported by NBU interventions for many years. All exporters lamented that the government did not know what it was doing. The result came fast: hryvnia tumbled to UAH 8/USD that fall, after several months of devaluation, with all the familiar consequences. Going through the same process now would be very bad for Ukraine. The country’s leadership needs to learn from past mistakes.

A tangled budget

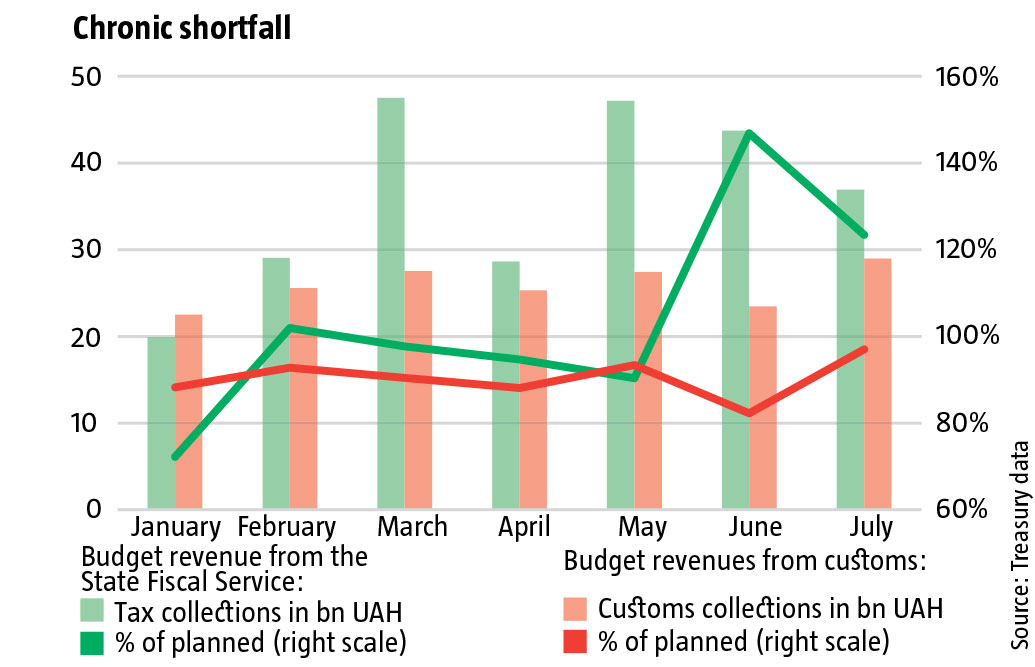

The third negative is an underfunded budget. While President Zelenskiy scolds Customs officers and fires heads of regional offices, this doesn’t change the main problem: shrinking revenues from Customs are mostly the result of the shrinking dollar and the customs valuation of goods linked to it. So far, Customs has failed to meet revenue plans in any of the first seven months of 2019 (see Chronic shortfall), leading to a shortfall of UAH 19.2bn for January-July.

The budget situation is tricky. On one hand, uncollected revenues lead to an unplanned increase in the budget deficit because the treasury received UAH 21.9bn less than planned. On the other hand, the Ministry of Finance attracted an unexpectedly large volume of cash with oversubscribed government bonds. This has helped it to cover the deficit: the net worth of government bonds issued over January-July 2019, UAH 47.7bn, i.e. issue less redemption, and non-resident bond holdings grew by UAH 80.1bn. This means that foreign investors have de factotaken over part of NBU and commercial bank government bond portfolios. The combination of these two trends has kept the Ministry of Finance in surplus for now: the treasury single account had close to UAH 49bn by early August, a record for nearly two years. But how long this money will last if foreign investors change their minds about the attractiveness of Ukraine’s government bonds is anyone’s guess

And so, non-residents buying government bonds is pushing the dollar and budget revenues down, and the hryvnia and the budget deficit up. The net outcome of this tangled trend is twofold. Firstly, government debt is growing faster than it should, which is generally not good, especially with the prospect of a new IMF program. The Fund will insist on tough controls over the deficit that are not now in place. Secondly, the economy is getting more funds from the state than it otherwise might, which is stimulating growth: GDP grew an impressive 4.6% in Q2’19 compared to Q2’18, and tax inflows increased in June and July (see Chronic shortfall). This looks great – but only for now. And this raises the question of the quality of GDP growth. At the moment, there’s no data to evaluate it in depth.

A combination of fiscal and monetary stimuli, with the NBU lowering the prime rate, could quickly overheat Ukraine’s economy. If it is fundamentally unprepared for such massive stimulus, inflation will pick up. This is yet another red flag for non-residents to prepare to leave. When these red flags – a cheaper dollars, lower prime rate, overheated economy, and inflation – reach critical mass, investors will start moving out. There will be no time for analysis or balanced decisions. To be fair, most government bonds issued by the Finance Ministry in recent weeks have a maturity of more than one year and have drawn tens of billions of hryvnia. This is good because it makes it more difficult for “hot” money to flee. Still, the government should avoid that kind of scenario with better balanced tax and budget policies, rather than trying to restrain it manually on an emergency basis.

Bucking world trends

The most interesting aspect of this web of developments and trends is that the international context does not match the situation in Ukraine – and this could eventually affect the country’s economy. Global stock, bond and forex markets are very tense right now. American protectionism is one of the causes, as new belligerent measures are introduced on a regular basis now. This is undermining the dynamics of global trade, along with industrial and economic growth in most countries. Currency markets reflect this fully. The MSCI Emerging Markets (EM) Currency Index fell 3% in August. The euro lost 3% against the dollar, the pound lost over 5%, Polish zloty went down nearly 5%, the Chinese yuan fell 3%, and the Argentinean peso lost almost 50%. Most world currencies devalued, while hryvnia went up 10%! And not thanks to fundamental economic factors.

Clearly, this exceptional revaluation will have consequences. Economic proportions have changed seriously. According to NBU estimates, the real effective exchange rate (REER) for the hryvnia was 0.93 in June, just 0.5% below December 2013. This means that hryvnia has lost all of the competitive advantage it gained as a result of the 300% devaluation during the 2014-2016 crisis. Price growth in the country and currency devaluation in its key trade partners lay behind this result. July and August figures will undoubtedly be worse. It will then be obvious that the situation today is more threatening than that in late 2013, when exporters were simply stifled by an overpriced hryvnia and non-competitive exchange rate.

If ruinous global trends continue, national currencies may devalue further. If the hryvnia grows or stays at the current level in that context, the global situation will become another factor compressing Ukraine’s spring and bringing the moment it breaks that much closer. It will be too bad if Ukraine is not ready for this.

Fight bubbles with policy

The current situation points to another parallel with mid-2008. The crisis was already unfolding in the world then – the US’s problems with an overheating real estate market were already evident in 2006 and economic growth began slowing down then – even though the really painful manifestations emerged in the fall. Ukraine was experiencing a full on hot money rush. First, foreign investors had been bringing in billions for several quarters in a row, driving the hryvnia from UAH 5.05 to UAH 4.65/USD. When the dollar got cheap, investors rushed to record their profits and withdraw capital. The tail of the hot money was wagging the dog of economic fundamentals. Today, there is every sign of the same happening again. This is a serious threat to the country’s financial stability and economic system.

The problem is that those in charge are not acting constructively. MinFin is blaming the NBU for being too passive with interventions, urging it to buy up foreign currency more aggressively in order to stop the devaluation of the dollar. The NBU is simply balancing out excessive fluctuations on the forex market, intervening only when the dollar loses value too steeply within a day or a week. In reality, neither the Ministry of Finance, nor the NBU is offering a policy to solve the problem. MinFin could issue fewer government bonds to reduce the influx of foreign currency from non-resident investors.

RELATED ARTICLE: Cloud on the horizon

The latest auctions for government bonds suggest that the Ministry has actually started doing so. The next few weeks should show whether this is so or the Ministry just took a summer break. The NBU could treat the balancing of exchange rate fluctuations as fixing excessive deviations from a certain yearly average, such as the exchange rate used in the budget, rather than as offsetting overly steep fluctuations within a given trading session. None of the two is demonstrating the necessary fiscal leadership or taking effective steps to coordinate policy, although the current situation desperately requires real coordination. It will be extremely difficult to lead the economy out of the cave of increasingly frequent threats otherwise.

If an economic crisis unfolds in the world, and the reasons for one are many and growing, Ukraine could benefit from following Poland’s example in 2008-2009: this was virtually the only neighbor that avoided a drop in GDP. The price, however, was devaluing the zloty by 40%. Ukraine’s economic system, including the banking sector, needs to be extremely well tuned and government agencies need to be proactive if they are to prevent the current dollar devaluation from triggering ruinous processes. How prepared is Ukraine for such a long-distance swim?

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook