As election fever goes into full swing and politicians stoke the fears of ordinary Ukrainians by talking about the supposedly “catastrophic” state of Ukraine’s economy, the reality is that most oblasts have already returned to pre-war levels of economic growth and some have even passed 2013-early 2014 indicators. What’s more economic growth is picking up pace across the board. In 2017, GDP grew by 2.6% in Ukraine, while in QI’18 it was up to 3.1%, and up again to 3.6% in QII. Still, the situation on world markets is poised to hit Ukraine’s weak spots hard in the not-too-distant future, so the pace the country needs to reach for long-term, sustainable growth requires a cardinal change to its economic policies.

An expanding growth zone

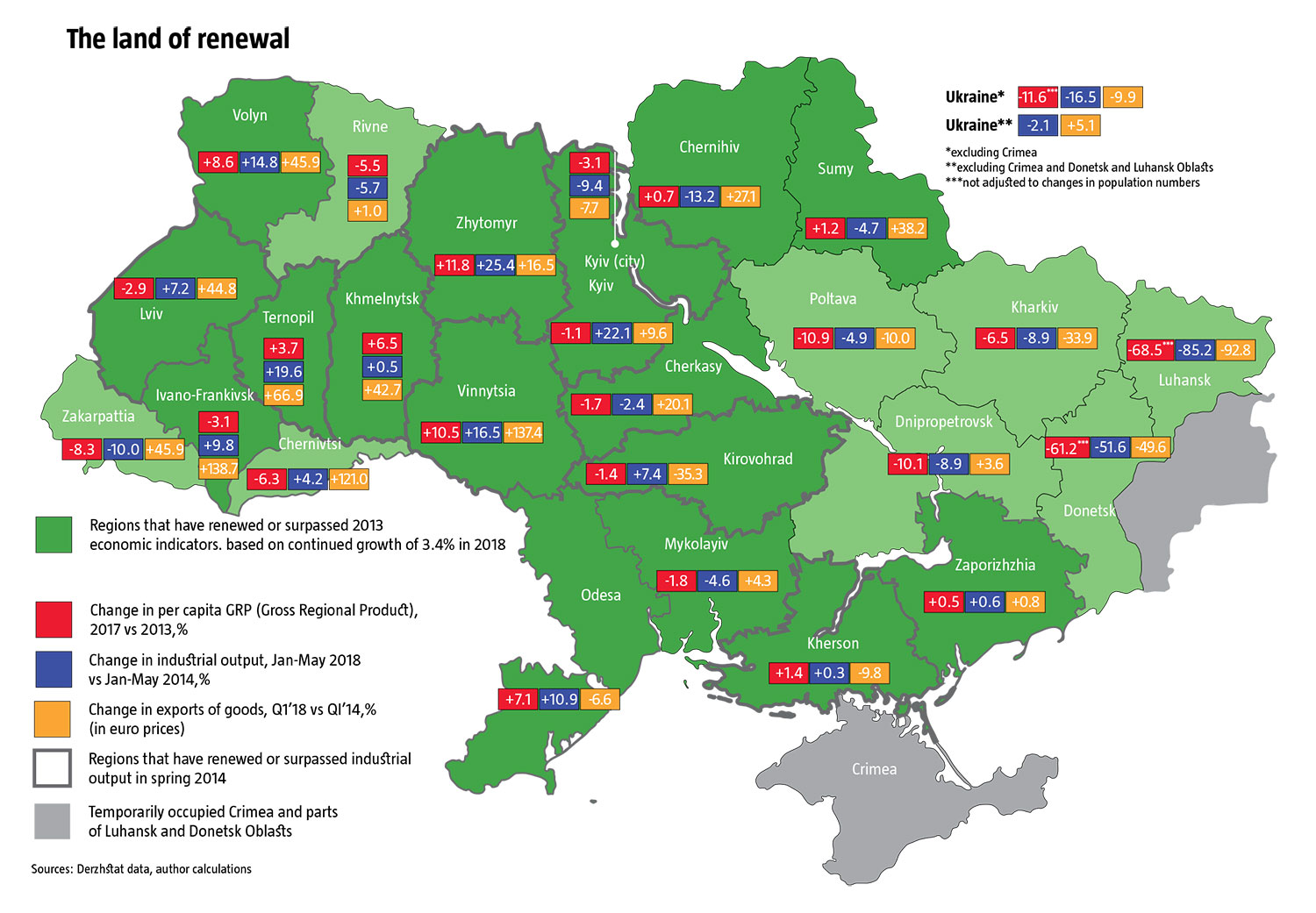

According to Derzhstat, the statistics agency, 2017 GDP was about 11.6% below 2013 levels. Once occupied Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts are taken out of the calculation, however, GDP was only about 2% below 2013 levels, which reflects the pace of population drop-off in the rest of Ukraine over the last four years. Once growth is broken down by oblast, this improvement becomes even more distinct.

Compared to pre-war 2013, the growth leaders continue to be two neighbors in Right Bank Ukraine, Vinnytsia and Zhytomyr Oblasts, which recorded per capita GRP in 2017 that was 10.5% and 11.8% higher than in 2013. Indeed, Zhytomyr outstripped Vinnytsia last year. Meanwhile, Khmelnytsk Oblast has been quickly catching up to them, with GRP 6.5% up from 2013 and 9.0% up from 2016; Odesa Oblast posted 7.1% over 2013 and 6.6% over 2016; and Volyn Oblast posed 8.6% over 2013 and 3.3% over 2016. Even Ternopil Oblast posted 3.7% over 2013 last year and was 3.6% up from 2016.

RELATED ARTICLE: The five whales

In this way, three oblasts that posted significantly higher growth in 2016-2017 than they had in 2013 were joined by three that now effectively establish a solid band from Odesa’s Black Sea shoreline to the Volyn border with Poland—if it weren’t for Rivne Oblast. To the east of this strip, two nascent “horns” are formed by two oblasts each that extend the positive trend, albeit not so substantially, as they, too, passed 2013 per capita GRP growth in 2017. Going to the northeast are Sumy Oblast with 1.2% and Chernihiv with +0.7%, while going to the south are Kherson with +1.4% and Zaporizhzhia with +0.5%.

These horns of improvement to the east are separated from the six boomers by four oblasts that are still moving towards recovery: Kyiv, Cherkasy, Kirovohrad and Mykolayiv. Their per capita GRP was only 1.2-1.8% short of 2013 results. Given that average annual growth today is 3.4% since the beginning of 2018, these oblasts will probably also reach recovery levels and join the Right Bank body to its four-Left Bank oblast “horns.”

At this point, we’re looking at 14 out of 25 regions of free Ukraine in which economic growth has reached or substantially surpassed pre-war indicators. These 14 neighbor on three more regions—the city of Kyiv, and Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts—where the latest figures show that their GRP was around 3% lower in 2017 than prior to Russia’s invasion. If economic growth keeps pace at 3.5-3.6% this year, these three regions could also recover to 2013 levels, especially since Kyiv, at 7.4%, and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, at 6.3%, were among the growth leaders in 2017.

Mixed news elsewhere

The three remaining western oblasts—Chernivtsi, Zakarpattia and Rivne—are, for now in far worse shape than five years ago. The level of decline there is comparable to the three oblasts closest to the war zone in Donbas: Kharkiv, Poltava and Dnipropetrovsk. So far, none of these six appear close to recovering.

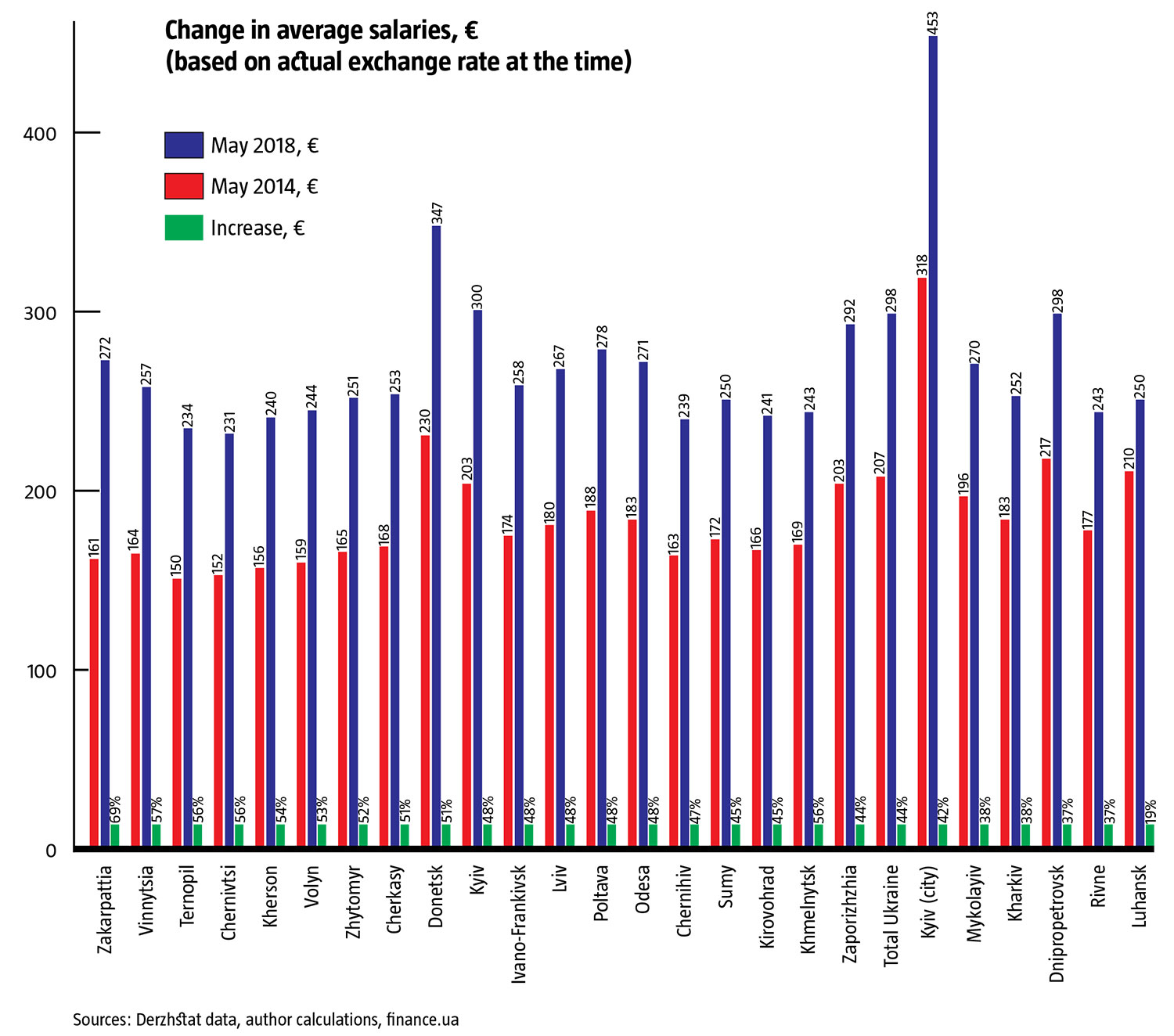

Moreover, a higher pace among the oblasts in the growth belt centered on Right Bank Ukraine has not led to growing wealth or a higher economic level already today. Mostly these oblasts are closing the gap with the previously successful oblasts. Indeed, varying degrees of growth and dynamics don’t always convert directly into higher incomes for residents of these regions. A comparison of average salaries in euro terms for May 2014 and May 2018 shows that nationally they are 44% higher (see Change in Average Salaries). Even taking inflation into account, most regions have already seen this indicator restored to early 2014 levels.

Taken individually, however, the situation varies wildly and there are plenty of paradoxes. For instance, in Ternopil and Vinnytsia Oblasts, which are in the top five for economic growth since 2013 at 3.7% and 10.5%, average wages were 56-57% higher in May 2018 than they were in May 2014. Meanwhile, in Zakarpattia, whose economy continued to contract, by 8.3% this past year, average wages have not only grown the most substantially in Ukraine, at 69%, but are also considerably higher than in regions with the best economic results in recent years. On the other hand, Odesa was one of the leaders in per capita GRP growth at 7.1%, yet average salaries in May 2018 were barely higher than the national average at +48% and were lower than the average wage in Zakarpattia.

Industrial output has also showed mixed results compared to overall economic results. Indeed, a return to pre-war levels can be seen at the same time as the general state of the regional economy is considerably behind 2013 levels. In some oblasts, however, total GRP has recovered while the industrial sector continues to lag. At the same time, there are some general trends in industry, with the growth belt doing the best. Some shifts have happened since 2013, as well. For instance, Kyiv Oblast has seen 22.1% growth in industrial output compared to early 2014, and is second only to Zhytomyr with 25.0% growth. Vinnytsia, by contrast, has fallen to fourth place and both Vinnytsia and Zhytomyr have seen industrial growth sag this past year. Meanwhile, western oblasts—Ivano-Frankivsk, Lviv, Chernivtsi, Volyn, and Zakarpattia — have seen industrial output pick up and all but Zakarpattia have already passed the levels they saw in spring 2014. Odesa and Kirovohrad Oblasts have also surpassed 2014 levels, while Zaporizhzhia, Kherson and Khmelnytsk have recovered.

Altogether, industrial output is now at least the same as early 2014 or significantly higher in 13 of free Ukraine’s 25 regions. Five more oblasts are within 2.4-5.7% of recovery. Since official statistics include industries located in ORDiLO, thereby distorting the picture in Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts, when these two are left out of industrial comparisons, Ukraine ends up with just five regions — the city of Kyiv, Zakarpattia, Chernihiv, Kharkiv, and Dnipropetrovsk — were industrial output remains 9-13% below 2013 levels.

What’s more, any decline should not be linked to the war in the east for most oblasts: the worst industrial results are in Zakarpattia and Chernihiv, and not in the frontline oblasts of Kharkiv and Dnipropetrovsk. And both Zakarpattia and Chernihiv are starting to see relatively dynamic growth. In short, some oblasts saw industry pick up pace while others have watched it decline, but this has often been because of the high proportion of enterprises in key sectors that have not adapted well to the situation on global markets.

If we look at changes in industrial output across the country without including the statistically distorted data for Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts, it turns out that it’s not much lower than it was in early 2014. For instance, for January-May 2014, the share of Donetsk Oblast in all domestic industrial output was 17.5%, while that of Luhansk was 6.3%, so the loss of 85.2% of Luhansk Oblast’s output compares to the 5.4% loss nationwide, and 51.6% lost in Donetsk compares to 9.0% nationwide. Of the 16.5% decline in industrial output over January-May 2018 compared to the same period in 2014, 14.4% was due to these two oblasts, leaving the real decline in the last three years only 2.1%.

Outside influences

The revival of Ukraine’s economy, especially in the growth belt is very closely tied to unusually dynamic growth in neighboring EU countries over the last few years, where the pace of growth has been far higher than in Ukraine as a whole or even in the individually most successful regions over this same period. The most positive growth was seen in Romania, where 2017 GDP was 20.1% higher than in 2013 and the country posted a further 4.3% growth for the first half of 2018 compared to 2017. Poland’s economy grew 15.5% in the last four years and 5.0% in HI’18; Slovakia grew 14.1% and 3.8%, while Hungary grew 14.5% over this period and added 4.5% in HI’18 compared to 2017.

Unusually dynamic growth in eastern EU members in recent years has been one of the key factors that stimulated strong growth in Ukraine’s more successful regions as they have been increasing their trade with the EU, especially with countries in the border region. For instance, total exports of goods from Ukraine to just four EU members—Poland Slovakia, Hungary and Romania—grew from €4.08bn in 2013 to €4.91bn in 2017. Exports to Poland alone jumped 25.4% from €1.92bn to €2.41bn, while to the most dynamic in the group, Romania, they grew 76.3%, from €0.42bn to €0.74bn. So far, this trend is holding.

When export volumes are compared for QI of 2014 and 2018 while leaving out Crimea, Luhansk and Donetsk, they grew 5.1% or from €7.92bn to €8.33bn. Most of Ukraine’s regions have adapted well to the new realities, and the most active exporting activity can be seen in Right Bank Ukraine. In fact, some oblasts have increased exports of goods 50-150% (see The Land of Renewal). For instance, exports from Vinnytsia and Ivano-Frankivsk Oblasts went up 140%, Chernivtsi’s increased 120%, Ternopil saw 70% growth, while Khmelnytsk, Lviv, Zakarpattia and Volyn saw a 43-46% increase.

But further east and south in Ukraine the intensity of exports on a regional basis compared to 2013 has gradually gone down and now volumes are beginning to shrink. Most southeastern oblasts have seen a considerable decline in export volumes compared to early 2014. In Kharkiv it is -34%. In contrast to the dynamic four years ago, today Vinnytsia’s €272.0mn in exports beats Kharkiv’s €223.8mn, just as Lviv’s €363.2mn beats Odesa’s €339.0mn. The biggest declines in Donetsk and Luhansk, at -49.2% and -92.8%, are primarily due to the loss of industrial enterprises to Russian occupation. In those parts of the two oblasts that are not under occupation, exports have actually been growing, especially in the steel industry in Donetsk Oblast.

Meanwhile, Ukraine’s eastern and northern neighbors have experienced a far more negative economic situation than the country’s western ones. Russia’s real GDP growth in 2016 was actually 0.6% below 2013 results and since the beginning of 2018, its economy has been growing half as fast as Ukraine’s. According to Rosstat, Russia’s economy grew only 1.6% in HI’18, compared to Ukraine’s 3.4% and the 4-5% growth posted by its EU neighbors.

RELATED ARTICLE: The cost of a good wage

Of course, those oblasts that have less successfully re-oriented themselves on alternate markets have suffered the most. Exports to Russia have collapsed from €11.1bn in 2013 to €3.48bn—and not only or as much as a consequence of mutual sanctions and the war. The thing is that as Russia’s economy has contracted, imports from other countries have also gone down, especially former soviet ones. According to Rosstat, total imports into Russia collapsed from $315bn in 2013 to US $182bn in 2016, but they managed to recover somewhat in 2017, to US $227bn. In Belarus, which is very dependent on export markets in its biggest neighbor, the decline of Russia’s economy has meant that Russian exports fell from US $16.8bn in 2013 to US $10.9bn in 2016, while volumes in 2017 were 2.3% below 2013 levels.

An uncertain future

For a country as poor as Ukraine, unfortunately, the current pace of recovery and growth is far from enough. Moreover, simple recovery to 2013 levels or even to the much higher levels in pre-crisis 2008. If Ukraine wants to leave the third world behind and join the first as a developed European country, it needs to get out of its downward spiral, where every new economic cycle of growth and decline ends with its economy in even worse condition.

What’s more, the external factors that have been so favorable for exports, for instance, could easily become extremely negative for Ukraine’s economy in its current form. Ukraine also risks discovering that today’s “difficult economic situation” was actually the verge of economic recovery. The world economy, especially its raw materials sector, appears to be more and more under threat of the next cycle of a planetary crisis. Today, such a crisis could be provoked by a growing confrontation among key economic centers around the world. With a growing economic crisis, the strongest economies could resort to more and more trade barriers, which will hit the raw material and especially the semi-finished product segments of Ukraine’s economy the hardest.

And so, recovery is happening, but Ukraine will only be able to push off from the bottom and hit a high pace of growth in the face of ever more aggressive conflicts for a “place under the sun” if government policy radically changes its priorities. It’s high time that the philosophy of redistribution and feeding on the shrinking wealth of the country is abandoned and replaced by a focus on growing national wealth and establishing principles of distribution that will force everyone to engage as much as possible in multiplying this wealth.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook