Here, the wounded arrive straight from the front lines—dirty, bloodied, stinking, and sometimes teetering on the edge of life and death. But arriving here means a chance at life. Well, perhaps not for everyone and not every time. Some face a long and arduous journey here, some don’t survive the trip, and for others, hope proves incompatible with life. Sadly, not everything rests solely on the shoulders of the doctors. However, for those fortunate enough to be rescued from the fray, those who miraculously find themselves here, this place is undeniably a beacon of hope.

Here’s an opportunity to cling to life and begin anew. They’ll support you, even when strength wanes, and they won’t give up on you. They’ll exhaust every avenue, possible or impossible, to ensure the soldier’s survival. They’ll go to great lengths, both possible and impossible, to ensure the soldier’s survival. They’ll persevere even when it feels like there’s no hope left. And sometimes, despite the severity of the injuries, miracles occur. Like the moment when, after 20 minutes of resuscitation attempts, someone unexpectedly springs back to life. Anything is possible.

Certainly, in the face of a sudden surge of casualties and limited resources, prioritisation becomes imperative. Quick decisions must be made about who can be effectively treated, with those most likely to survive receiving immediate attention. Unfortunately, this means some may receive less urgent care or none at all. In such dire circumstances, the principle emerges: priority is given to those with the best chance of survival.

And when civilians and soldiers are weighed against each other, military personnel typically take precedence. This is war…

I’ll steer clear of mentioning specific places and people in my writing to keep things safe and simple. In times of war, even a small slip-up or unnecessary info can cause big problems. Plus, we don’t really do formal intros or nosy questions around here. If someone needs to know something, they’ll find out. All the important stuff is in the “hundred” (Form 100, or “wounded card”) that comes with the injured folks. I’ll just say I’m thankful for spending this day in this little corner of the world. Seeing real people doing tough but important work, saving our defenders, is something special.

It was Thursday, around noon. The guy who just got evacuated from the front lines and handed over to the docs hit the jackpot—he’s gonna pull through. Lucky break, considering the blast from an enemy mine. His injuries weren’t too bad by local standards: a chin graze, some hits to the left thigh and right wrist, plus a tiny scratch on the left. Surprisingly, he walked into the makeshift operating room himself, stripped down, and hopped onto the table. They didn’t give him the full check-up right then and there, just patched him up as best they could and shipped him off for evacuation. Lucky him again—got whisked away from the front right after getting hit. No waiting till nightfall this time, which is usually the deal nowadays.

Today, daytime evacuations are nearly nonexistent. Perhaps in certain isolated pockets of the frontline where conditions permit or where nighttime evacuations are simply not feasible. But here, it’s a different story. Even at night, safely transporting the wounded can be challenging due to the constant threat of kamikaze drones overhead.

In the past, military medics aimed to administer first aid as swiftly as possible, minimising the gap to zero and recognising the critical importance of every moment. However, the landscape has drastically shifted. The frontline is now swarming with drones, and both doctors and evacuation vehicles are prime targets for the enemy. Consequently, it’s practically untenable for medics to operate in those conditions. And sadly, the shortage extends beyond just medical personnel. “We’re running low on medics too,” the doctor at the stabilisation point laments.

Photo: Roman Malko

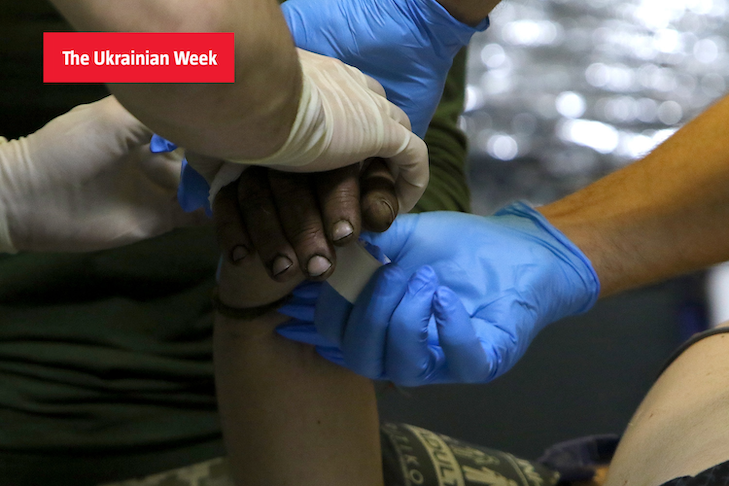

While the female surgeon sews up the soldier’s chin, her colleague attempts to clean the soldier’s arm, which also requires stitches. However, it’s proving to be quite a challenge. The grime has been deeply embedded into the skin, resisting all the chemical solutions available in the operating room. His arm remains discoloured.

Once the soldier has been treated and his wounds dressed, he’s clothed in civilian attire – a sportswear ensemble, a T-shirt, and socks – before being ushered into a nearby room to recuperate. The clothing isn’t brand new, often ill-fitting, but at least it’s clean. It’s deemed unwise to redress the wounded in their old military uniform post-treatment. Besides, more often than not, the uniform ends up in tatters, having been ripped off the person during the ordeal.

At the first opportunity, the patient will be sent to a regular hospital, but not before nightfall. That’s when an influx of wounded can be expected. After receiving assistance, they are grouped and loaded onto evacuation transport, taking them as far away from the combat zone as possible.

Since the beginning of the year, there has only been one night when only five wounded were brought in, and even then, they weren’t too severe, allowing the next shift to get some rest. Some of the doctors didn’t even have to be woken up then, and they sincerely wondered what had happened in the morning. But tonight, most likely, it won’t be like that. From early in the morning, you can hear frantic rumbling on the horizon. Heavy fighting is going on somewhere; the Russians are trying to break through our defence line, so with the onset of darkness, we should expect an influx of wounded.

“On the bright side, there’s hardly any daytime work, barring a few cases,” the nurse explains, “see, we are being lazy here,” she adds with a bitter smile.

“It’s all because of the drones,” her colleague adds, “It’s actually a good sign when we’re not busy; it means no one got hurt. But that’s just for now. War keeps evolving, and we’re adapting and working in any situation. There were times when we could reach the front lines ourselves, but our equipment couldn’t. We stabilised patients in trenches and bunkers and then called for transport.”

“The lack of armoured evacuation transport is an ongoing problem in this war,” says the anaesthesiologist, “they transport wounded on anything that comes handy… on pickups, on buggies, and motorcycles.” “And don’t forget the good old stretchers,” laughs the female surgeon. “The guys from the neighbouring brigade bought themselves a robot on tracks,” continues the anaesthesiologist, “he reaches the wounded, and they grab onto it. But it can be easily disrupted by electromagnetic warfare. The system needs to be changed and reconfigured. Except that, afterwards, its value would increase to 600-700 thousand hryvnias (15 thousand euros), and that’s very expensive. You can buy a Czech robot that’s impossible to disrupt. “But when you consider the costs, that’s already 10 million (240 thousand euros)…” The anaesthesiologist paused, reflecting on the staggering figure. “Imagine what we could achieve if every unit had armoured evacuation vehicles,” the female surgeon chimed in, her voice tinged with both frustration and determination. “We could evacuate more, reaching those in need faster and more efficiently, ultimately saving more lives. But alas, as it stands…”

“In 30 minutes, we’ll have a severe case,” the nurse alerts, her tone tinged with urgency. “Firearm injury to the left forearm.”

When a wounded soldier is evacuated from the front line, their details, documented on Form 100, are swiftly relayed in the general chat. This vital information ensures that the medics at the stabilisation point are well-prepared, aware of the nature of the injury, and ready for the incoming patient. Meanwhile, as the patient is en route, the medical team readies everything necessary for immediate treatment.

As the clock strikes 21:40, darkness blankets the surroundings. Into the operating room arrives a stretcher bearing a wounded soldier. With utmost care, they transfer him onto the table, mindful not to exacerbate his pain. Apart from the visibly mangled arm, tightly bound by a tourniquet, the soldier bears multiple burns across his body, notably extensive on his back. Despite the administered pain relief, the process of cleansing his wounds elicits excruciating pain, causing the soldier to writhe in agony with every touch from the doctor. Yet, remarkably, he endures in stoic silence, save for the occasional groan when a urinary catheter is inserted, the pain now reaching unbearable levels. Nonetheless, there’s no alternative but to proceed.

Around midnight, a message appears that they are bringing in two more severe cases. They arrive simultaneously, placing one in the corridor while the other is taken directly to the surgery room. This is a serious case – lots of injuries all over the body, so he needs to be seen by the doctors quickly.

But even the one in the corridor is not left unattended. The doctors not involved in assisting the first patient quickly cut off his clothing, placed a catheter in his arm, and administered the necessary medication. To keep him from getting cold, they cover him with a golden thermal blanket. Someone also verifies his personal information and writes it down in a notebook. Hearing the wounded person’s response, I catch myself thinking that he’s my age.

Photo: Roman Malko

The man lies face down, groaning softly. His legs, buttocks, and back are riddled with small shrapnel fragments from an explosion nearby during transit. The injuries inflict considerable pain. Resting on the stretcher, he feels uneasy, prompting him to shift his head continuously. His comrade, the one who brought him here, must already be on his way back. Leaning in close, he offers comforting words, gently stroking his friend’s head, assuring him that everything will be alright. The wounded man responds only with groans. As a parting gesture, the man kisses his friend’s grimy hair and then, somewhat perplexed, makes his exit.

The process of extracting the shrapnel will be time-consuming. Some fragments will remain lodged in his body indefinitely, some are too risky to remove. Once his wounds are treated, the soldier is rolled onto his back for a thorough examination. Luckily, there’s nothing on his front side. After a few more procedures, he’s transferred back onto his stretcher and wheeled into the corridor. He’ll have to wait here until a room frees up. The initial group of stabilised patients was recently evacuated, but new arrivals quickly took their spots.

By morning, severe cases will be minimal, mostly comprising lightly or moderately injured individuals. At one point, there’s even a long line of uniformed personnel outside the operating room, all walking in under their own power. Some require a bandage for minor head wounds, while others present with typical concussions. Then there’s someone who developed a sudden ulcer in the trench, urgently needing medical attention.

“It started with a hit to my back, then the explosion, and I went headfirst into the trench wall,” recounts one of the patients, providing a detailed account to the doctors. “I felt the pain in my back, blood flowing, slapped on a sticker, and that’s all.” “Was it from a drone strike?” the doctor inquires. “Yes. Fortunately, I had my jacket on, a shirt. It pierced the fabric of the armor and got stuck. If I hadn’t been wearing anything, it would have gone straight through.”

The soldier, approximately fifty years old, sturdy, with a magnificent beard, mentions that it’s not his first encounter with enemy fire (when a grenade is dropped from a drone). In fact, it’s his fifth injury during the war. He keeps insisting that the doctors make sure they remove the shrapnel.

“Now, now, let’s have a look,” says the doctor, “we have to see if it’s magnetic or visible enough for us to remove.” “It won’t be magnetic,” the soldier replies, “there’s no metal in the grenade.” “And you wouldn’t want it to stay in you?” the doctor asks further.

“I already have five in my body. Enough,” the soldier says, “I won’t be able to pass through the metal detectors; it’ll beep. One in the head, one in the chest, in the leg… How many more!” “No, that’s too much,” the doctor smiles, “I agree. Let’s try now. Turn back onto your stomach.”

After peeling off the sticker and sanitising the wound, the female surgeon readies a syringe for the painkiller. “You’re going to feel a little prick,” she warns. “No worries, I’m not scared of syringes,” reassures the soldier. “Oh! How odd,” remarks the doctor, “it’s been a while since we had someone not terrified of needles. Usually, boys fear them more than their wounds.”

The surgeon delicately probes the wound, searching for the shrapnel, but with no luck. The soldier winces in discomfort. “Does it hurt?” she asks. “Yeah, but I’ll manage,” he replies, “just get it done. It’s not too deep. I had one lodged in my head in Rivne; you know how much that bothered me. Just cut and tweeze it out.” “Trying to extract it blindly isn’t safe,” the doctor intervenes, “unfortunately. They’ll take care of it with an X-ray at the hospital. No need to worry.”

One of the doctors hands the soldier a clean white T-shirt, and he suddenly looks a bit embarrassed. He says he hasn’t left the frontline for a month and a half. He’s been living underground and hasn’t washed once during that time. “It’s alright,” the doctor winks, “you’ll clean up nicely with the T-shirt. Put it on.”

“If they bring soldiers back with nothing from the front line,” the resuscitator explains, “we tidy them up here, patch them up, and even provide some entertainment if needed.” She chuckles, “the full package deal.” “Some patients even sing,” chimes in the nurse. We patch them up, and off they go singing [a Ukrainian song – ed.] ‘Hutsulka Ksenia’.”

And the doctors are always cracking jokes. They jest while extracting shrapnel; they jest while stitching wounds; they jest while wrapping bandages. Surprisingly, it doesn’t bother the patients at all. If anything, if they’re in somewhat decent shape, they appreciate the distraction. “Humour is essential,” one of the doctors explains, “we’ve got no choice. If we don’t tackle all of this with a touch of humour, well, we’ll just fade away here. After all, we’re human too.”