Last year, Ukraine got some significant pleasant surprises. They are the record harvest of crops, the largest ever inflow of non-resident funds into domestic government bonds (T-bills), peaked in many years, economic growth rate exceeding 4% in II-III quarters. The average wage, expressed in hard currency, reached a historic high, crowning all of these positive developments, and real wages reached new heights. Ukrainians began to live better.

But wasn’t last year’s result a fluke? 2020 will answer this question and at the same time statistically substantiate whether the country is moving in the right direction. At present, the Ukrainian economy has a good starting position stemming from the 2019 gains. But the risks are considerable.

Once again about the crisis

Talking about the global economic crisis right now is a thankless task, since for the last few years; even those who are far from being experts in economy have been pestering it. The IMF also predicts that global GDP growth will accelerate from 3.0% in 2019 to 3.4% in 2020. That is, at first glance, there are no grounds for concern.

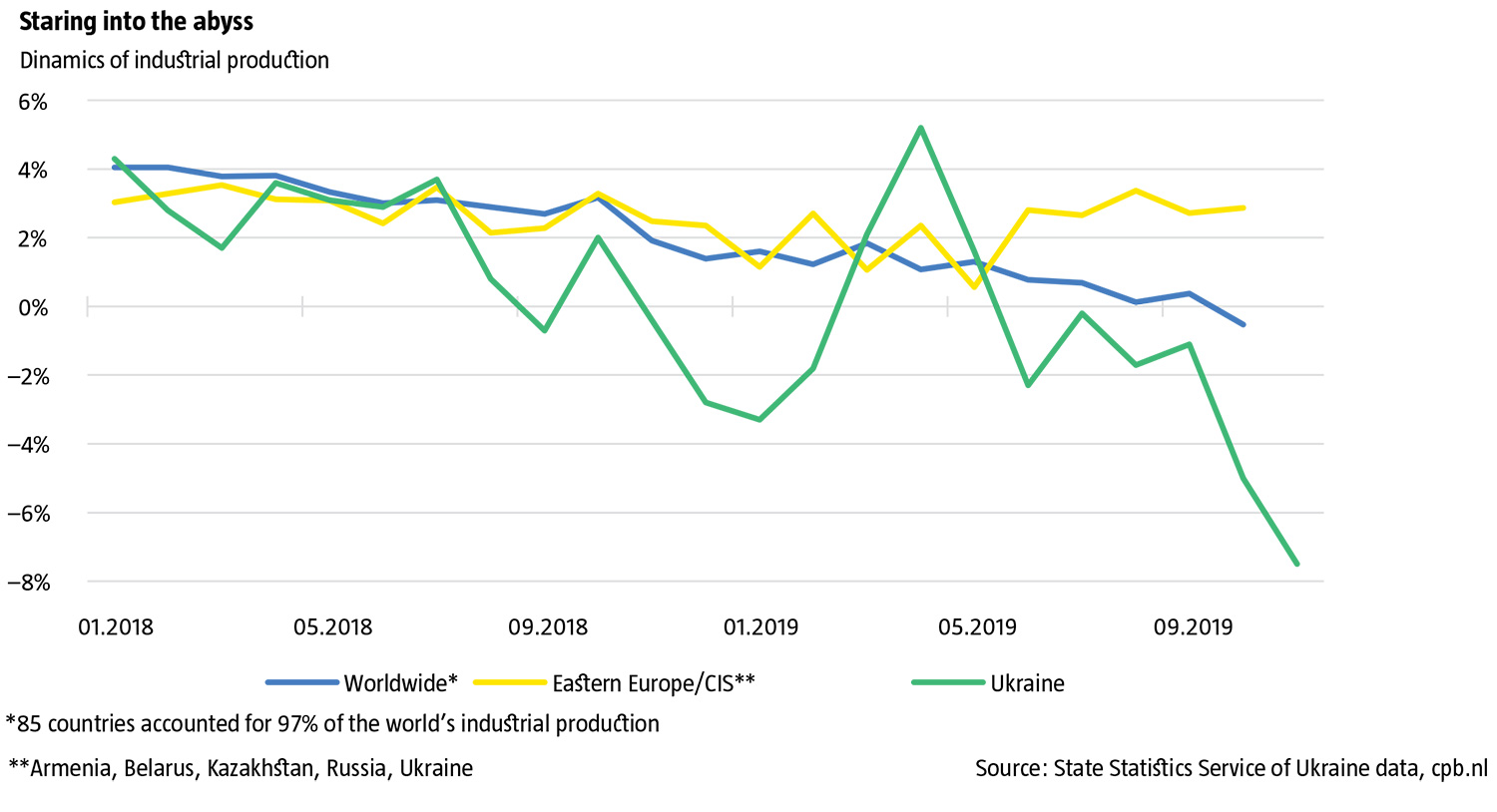

But trends are a stubborn thing. And many of them are negative today. Therefore, the question of deployment of crisis processes in the world has always been on the agenda. First of all, the growth of world trade has been steadily declining since the beginning of 2018. They have been negative since June 2019, -2.1% in October. This is the least since the 2008-2009 crisis. Along with world trade, industrial production is also slowing down (see Staring into the abyss). For a long time its dynamics was positive, but in October it dropped to zero and even below. The downward trend is very clear; no change for better is visible. This cannot be ignored, as industry accounts for a quarter of world GDP. So if the trend continues, the devastating effect will soon spread to other sectors.

How long will this trend last? It all depends on the factors that determine it. It is thought that the main reason is the uncertainty caused by the trade wars between the US and China, Brexit and geopolitical turmoil. Obviously, investments do not like uncertainty. Therefore, gross fixed capital formation (an indicator of macroeconomic investments) stagnates in the seven economies of the G20, and declines in Mexico, South Korea, Australia, Argentina and Turkey. The prominent British economist J.M.Keynes once spoke about the decisive impact of investment on business activity. If they fall in the five big economies and do not increase in seven, will this not be the springboard for crisis unfolding? Can we then rely on the IMF's predicted economic growth acceleration in the world?

Some believe that as soon as Brexit settles and the US signs a trade agreement with China, the uncertainty will disappear. It would be nice if this happened as soon as possible. But there is another opinion: the current rise of protectionist and isolationist sentiments is the reaction to the change in the world order that the Fourth Industrial Revolution is carrying. Until the framework of the new system of international relations crystallizes, such phenomena will occur again and again.

RELATED ARTICLE: A reality check

At the same time, let's look at car sales statistics. Last year, primary car registrations dropped in half members of the G20. Production declined in the two largest car manufacturing countries – the US and China, as well as ina number of others. However, basic needs to move around in a cardemonstratingyour standard of living have not disappeared. So where did the dynamics come from? Is it the result of protectionism, declining incomes, or the appearance of hoverboardsand Uber? In any case, the dynamics of car sales has little to do with investor sentiment. And car manufacturing combines the work of a huge number of related businesses and industries. The crisis in this industry is rapidly spreading throughout the economy. Therefore, it is very likely that the decline in world trade and industrial production has not yet reached its peak.

Another fact is alarming. These negative trends began to emerge between 2018 and 2019. The US Federal Reserve (FED) reacted last year in late July, launching a discount rate cyclewhich has already had three steps. Many other central banks have taken the initiative. But the problem is thatit has not affectedthe annual growth rate of many economies. GDP growth in the US, China, India and four other G20 countries is slowing further, while inflation has accelerated markedly. At present, soft monetary policy is bad for the real sector, but it nourishes wellthe stock market. In many countries, including the United States, stock indices are setting new records. But it cannot last forever. The higher asset prices, the greater the fear of collapse among investors and the less impetus required to start a collapse. And when that moment comes, the investment sentimentswill deteriorate for the long haul. Therefore, it is too early to talk about the recovery of the world economy. Rather, on the contrary. And this is a significant risk not only for Ukraine.

Weak Ukraine

The worst part of it is that the Ukrainian industry is not ready for long-term bottom testing. It is weak, underinvested, so its dynamics ischronically worse than the world’s oneand even regional (see Staring into theabyss). Because of this, at the end of 2019, our economy was reminiscent of a marathon runner who ran the distance well, but barely reached the finish line forexhaustion. During the year, the successes of other industries sidelinedindustrial production stagnation, but towards the end, the downturn in the industry became acuteand other sectors’gains diminished. All in alla gloomy picture with undesirably fast dynamicsbegan to form. And this is already a significant risk for 2020.

If the declining trend of world trade and industry is as unbroken as the chart shows, it will be a great challenge for the domestic industry. No matter how strong our agriculture is, its share in the gross value added of the economy is almost half that of industry. Therefore, it will not be able to counteract the marked decline in industrial production. And even if things are going well in other industries, industry-induced losses of employment, purchasing power and budgetary revenues may well chip away ataggregate demand over time and ultimately trigger the decline of the entire Ukrainian economy.

The last two crises have shown that when a downturn begins in the Ukrainian industry, its pace very quickly and smoothly develops to double digits, and sometimes exceeds 20%. Can this dynamics be avoided this time? It is difficult to answer unequivocally. But this risk needs to be given due attention, because much depends on how well it is assessed by the state and on appropriate economic policy put in place to counteract it.

Migrants’life-line

The official salary received by Ukrainian workers abroad has increased from $5.2 bn in 2014 to about $12.8 bn in 2019. More than $2.4 bn goes to us in the form of private money transmissions, which probably come from the income of illegal workers and Ukrainians who changed citizenship. There are twoconsequences. First, the export of people and labor from Ukraine has become a significant component of the balance of payments, since it already provides foreign exchange earnings equal to almost a quarter of the income from exports of goods and services. Dynamics of indicators indicatesthat it is much easier for a country to export people than products of itseconomy. It's not just sad. No matter how successful the reforms are, the scale of migration is their most accurate assessment given by ordinary citizens. In the human dimension, no development is possible without resources. Therefore, no government with a strategic state vision should allow for a chronic loss of human resources.

Secondly, now the balance of payments and the whole economy of Ukraine depend very much on the economic dynamics of the countries in which our citizens work. And this is a significant risk. On the one hand, it has a long life. It may not be realized in 2020, because over the 11 months of 2019, the official salary of Ukrainian workers has increased by more than 12% compared to the same period last year, so there is seemingly no reason to worry. On the other hand, the Ukrainians work mainly in the EU countries, whose economic situationsarevery uncertain. According to the IMF, the euro area economy is expected to accelerate from 1.2% in 2019 to 1.4% in 2020, but this is highly unconvincing given the dynamics of a number of macroeconomic indicators in the countries concerned. The economy of Poland has started a slowdown, which is likely to continue in 2020. If crisis trends increase in the world, then EU countries are likely to be among those who will get the most.

Over the last 10 years, the quality of labor migration from Ukraine has changed dramatically. Previously, Ukrainians in Europe worked mostly illegally. They stayed in one country and tried to make money there, living in constant fear of being deported. At the first manifestation of the crisis, they immediately lost their jobs and often returned to Ukraine. Now our labor migration is civilized, and workers have employment contracts. They have become freer, do not cling to one country and are ready to change, say, Poland to Germany if they receive a higher salary. As employment in Europe grows, demand for them is high. But, as before, in the event of a crisis, they will be massively deprived of jobs, because, choosing between a Pole and a Ukrainian, a Polish employer will probably dismiss our countryman.

Will this not affect Ukrainian labor migrants? Will their support for the Ukrainian economy remain as strong as before? It is difficult to say unambiguously, but it must be admitted that today the growth of the EU economy has become a matter of economic security for Ukraine. And this is long before any hint of our country's membership in the European Union.

Headwinds of capital

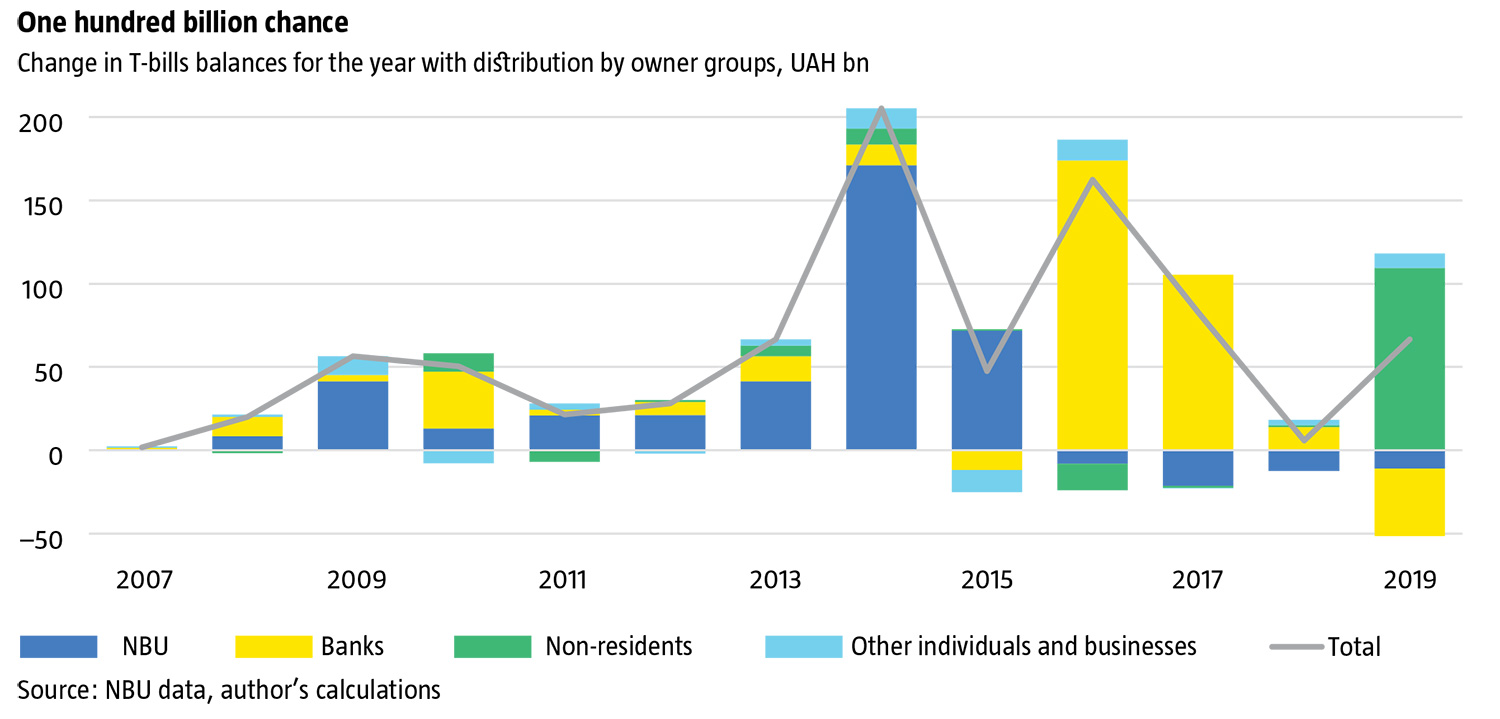

Last year, non-residents invested a record amount of nearly 110 billion UAH in T-bills (see One hundred billion chance). This is a phenomenal result, which is well ahead of previous years. Oddly enough, it also carries a significant amount of risk for the current year.

Let's start with the reasons. The high interest rate,associated with it, the high yields on government bonds and the lack of macroeconomic prerequisites for a noticeable devaluation of the hryvnia werea favorable foundation in early 2019. None of its constituents are atpresent. Rather, on the contrary. On January 14, the Ministry of Finance placed four-year hryvnia bonds with a yield of 9.88%. At the current exchange rate, it is uncompetitive compared to other countries with similar risks. Subsequently, investors will realize this and at least refuse to buy more government bonds. This is the first risk factor.

The euphoria associated with the change in power has also contributed. Before the presidential election, investors were wary of Ukraine's prospects. After the parliamentary elections, they believed in an ambitious program of liberal reforms, ignoring the weaknesses of the current government. In either casein 2020 this euphoria will disappear, because there will be real results, which will be very difficult to meet the extremely high expectations. This is the second risk factor. But that’s not the issue. The world financial and economic system is developing in microcycles that are somewhat like breathing. As the level of fear among counterparties increases, capital flows into “safe havens”– advanced economies with the least risk, such as those of theUS, Japan, and Switzerland. It's a breathing-in. When investors’feardecreases, capital flows in the opposite direction to developing countries. It's a breathing-out. Ukraine is one of the very risky developing countries, so we observea hypertrophied reflection of these processes. During breathing-out, golden rivers can flow to us, as if they were taken from nowhere, and during the breathing-in, it seemslike a seven-year Egyptian drought occurs during the time of the biblical Joseph.

Until the middle of last year, the world was paralyzed with protectionism, the decline of global trade, and the slowdown of the world economy. But when the FED, and after it, other central banks, began to act, that is, to ease monetary policy, counterparties heaveda sigh of relief. It was abreathing-out: capital flowed to developing countries. At the time, Ukraine was in good macroeconomic positions, so it received a full bag of money. The largest inflow of foreign money came just in July-August, when investors already realized that the FEDwould start operating and that relief would soon come.

The consequences of this werevery positive for the Ukraine’seconomy, so much so that many, including those in government, have becomeeuphoric and believed that our economy has reached a new level. It is a false impression, a self-deception, which also happened in 2005-2008 and we all know how it ended. The reality is that in the near future, accelerating inflation in developed countries will raise the question of the need of hardlinemonetary policy. The breathing-outphase will end, the breathing-inwill begin. Therefore, for Ukraine the rivers of gold can change to drought. And that's the main risk factor for 2020.

Questionable budget

Sometimes the euphoria dazzles and prevents you from really looking at things. There is much talk about the luck thatforeigners have invested hundreds of billions of hryvniasin government bonds. But no one is saying that in doing so, the NBU and commercial banks have reduced their investment by more than UAH 50 billion (see One hundred billion chance). In 2020, the government’s appetite for the domestic debt market will not diminish. And the demand of non-residents for government bonds is likely to fall, because now their yield is not too competitive, and the hryvnia exchange rate is not as attractive as a year ago. Then who will buy the government bonds? Will state-owned banks do this again under pressure from above? But the date of their withdrawal for privatization is approaching, which apparently implies an increase in their autonomy in decision-making. Will such plans have to be postponed? There is no clear answer to these questions, but there is a considerable risk of problems with the financing of the state budget. Of course, one can always return to cooperation with the IMF, but judging by the actions of the current government, it is in no hurry to do so.

The 2020 budget has somewhat a unique problem. A few years ago,too low dollar rate was included inthe state budget. As it grew more than projected, the Treasury received higher revenues than planned. This money covered the current gaps and even financed road construction in border areas for some time. Last year, on the contrary, the dollar exchange rate turned out to be unexpectedly low, which caused the plan to fall short of revenue. Then nobody really expected it. But this year is absolutely amazing: at the beginning of November 2019, the Ministry of Economy generated a forecast average annual rate for 2020 of 27UAH/ $, and the Ministry of Finance put it in the budget base.It happened when the dollar in the foreign exchange market was close to 24.5 UAH / $ and was declining steadily. In addition the Minister of Economy is also discussing the possibility of a rate of 20 UAH / $ in 2020.

The NBU does not publicly predict the exchange rate, as it intends to divert the economy from pegging to the dollar. The National Bank's motivation can be understood. But the dynamics of the exchange rate is a fundamental macroeconomic indicator, without which it is impossible to build a balanced economic policy of the state. How can the Ministry of Economy and the Ministry of Finance work without understanding the trends in the foreign exchange market? This whole story is another big risk for 2020. It is already manifesting itself. After all, either during the year, the dollar exchange rate will grow steadily from 24 to 30 UAH / $ to reach the forecast average of 27 UAH / $, or the budget revenue plan will not be fulfilled. The prime minister has already said in a handsome expression that the macro forecast will be revised in February. Where is the guarantee that the new forecast is adequate? And even if it is, you will have to look for extra income or cut costs. The economy will not be receptive to any of these operations.

Elusive exchange rate

In the second half of 2019, there was much discussion about the reasons of hryvnia becoming strongerand how it affects the economy. Meanwhile, the economic situation worsened: non-residents began to buy less government bonds, agrarians experienced problems with profitability, and the decline of the industry deepened. There is increasing statistical evidence thatinthe currenteconomic situation thehryvnia whichis too expensive isa risk to macroeconomic stability. Therefore, the main question at this point is whether the hryvnia will remain expensivelong enough for this risk to be fully realized.

It seems that the NBU has adjusted its strategy to work in the interbank foreign exchange market. On December 12, the regulator announced that it was raising the level of planned daily currency purchases from $30 million to $50 million, and since the beginning of the year its activity in the interbank foreign exchange markethas confirmedthe chosen behavior. This will keep the hryvnia from strengthening, it will destroy the counterparties' expectations of its further strengthening, and therefore, can fundamentally change the balance of supply and demand in the foreign exchange market. Then the dollar will go up. Can this process get out of hand? If there is such a risk, then it is one of the smallest. Obviously, within a year or two the dollar will try to fully play the lost position and even more. And itwill succeed if thecrisis processesgain momentum worldwide. But given the volume of the National Bank's foreign exchange reserves, a real upheaval is needed in order for the exchange rate to fluctuate sharply and jump beyond the highs of recent years. This is not expected yet.

RELATED ARTICLE: The coming crisis

Neutralize the threats

Ukraine must be well prepared to cope with these risks in view of their scale. It would be nice if the state had an ace up sleeve. Of course, the simplest option is the devaluation of the hryvnia, which can smooth out many minor problems. But it would be desirable for the economy not to slow down, to grow further and to acquire some immunity against internal and external threats. In this case, there will be little devaluation, especially in the worst case scenario.

What can the state offer? The first is the activation of lending. No wonder it is said much about now. The NBU’s discount rate should contribute to this. But is it enough to make the effect of an increase in lending significant for the economy? And will the state not leach out internal financial resources withits borrowings if non-residents stop buying government bonds? 2020 will answer these questions. For these questions to be constructive, the state must work hard.

The second is the launch of the land market. Even if this happens with draconian restrictions, the financial system and the economy as a whole will still receive a considerable sip of fresh liquidity. It will happen in all circumstances, because such events happen in the world every decade. The only question is whether it will have negative social consequences. The current year will answer this question as well.

The thirdis structural reforms. So far, it is a “latent anti-risk”, that is, it has existed for a long time and can be implemented in a positive way, but it does not happen in any way. Will 2020 be the exception? Without proper government efforts, no.

So, Ukraine is not in a state of hopelessness. We have significant risks, but we also see directions that we need to move to avoid a full-blown economic crisis.

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook