Ukraine’s “Energy strategy-2035”, the government’s energy development strategy plan adopted in 2017, has been widely criticised while it was still being drafted. Some experts were put off by the unsatisfactory indicators of the renewable energy sources’ performance, while others noted that potential economic crises were not really considered by the authors of this legislation. The long list of professional objections did not prevent the final bill from being passed by the Rada, Ukrainian parliament. The key idea of the proposed legislation was to replace such unsustainable energy sources as coal and gas with renewable sources as well as preserve well as develop nuclear power plants (NPP).

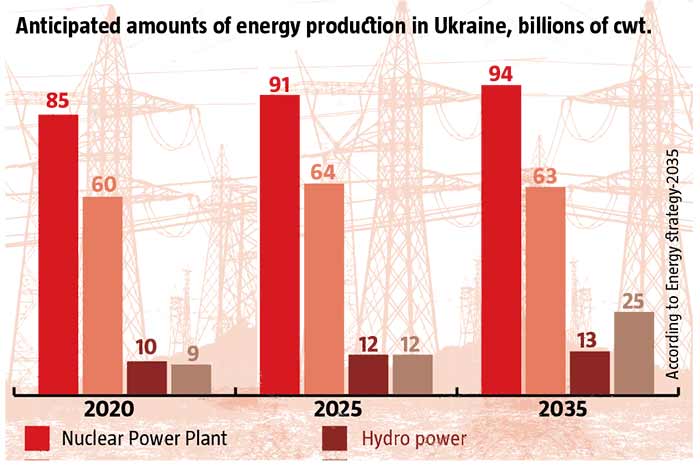

NPPs are likely to remain the principle source of electricity in Ukraine for the next couple of decades. According to the afore-mentioned legislation, throughout the coming year all active energy plants in Ukraine are expected to produce 85 billion of kWh of energy, or up to 52% of the overall country’s production. Until 2035 this proportion is not likely to change, although overall production levels are expected to increase up to 94 billion kWh. Authors of the bill proposed two options to reach this goal: extending the lifespan of the old energy generators and building the new ones. Very little details are being shared right now, however according to the proposed bill “the opening of the 1 Gigawatt NPP” is the matter of the next 6 years.

Authors of the above-mentioned legislation are talking about the completion of the facilities in Khmelnytska NPP, a nuclear power plant based in the city of Netishyn, in Khmelnytsk Oblast in Ukraine. This plant is currently operating two active reactors, while two more – reactors KhAES-3 and KhAES-4 – are planned to be put into operation in the future. Energoatom, Ukrainian state-owned enterprise operating nuclear power stations across the country, announced that it is anticipating to put KhAES-3 into practice by 2025. Energoatom has very few candidates to fill in the vacancy for the contractor, who would undertake such project. This lack of choice, however, raises more questions than answers when it comes to political, economic and safety consequences of the project.

There is not end to construction

On 8 August 2004 Ukrainian government officials, headed by then-president Leonid Kuchma, arrived in Khmelnytska Oblast to oversee the opening of the second, new reactor in Khmelnytska NPP. An ongoing presidential election campaign would subsequently culminate in Orange Revolution in autumn later that year. In his speech, then-president Kuchma criticized “the West”, claiming that the western countries had promised to financially support construction of the new reactor in return for Ukraine’s agreement to shut down its ill-famed Chornobyl NPP. Kuchma insisted that the “government had only managed to finalise the second reactor of KhAES and fourth generator of Rivne NPP owing to enormous efforts of the current government and [then] prime-minister Viktor Yanukovych”.

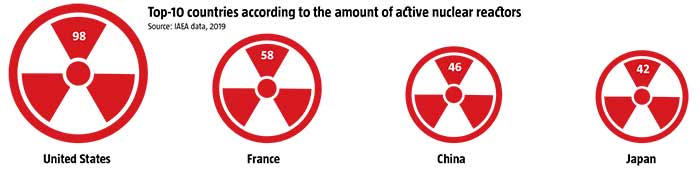

Ukraine has not put into operation a single new reactor ever since that day. There are currently 15 active reactors working on four different NPPs in Ukraine. Despite not being able to build any new facilities from scratch after regaining its independence in 1991, Ukraine did complete three different nuclear plant projects, which were initiated by the Soviet government. Ukrainian authorities have been actively developing KhAES-3 and KhAES-4 since 2005. Three years after, the country’s Ministry of Energy and Fuel announced a tender to select the type of reactor, necessary to complete the project. Energoatom invited five companies to participate, however only three of them agreed to take part in the process – American “Westinghouse”, Korean “KEPCO” and Russian “Atomstroyeksport”.

“The so-called ‘competition’ was held instead of a full-scale tender. The documentation was prepared in a way, that the winner was made obvious. Yes, undoubtedly it would be Atomenergostroy. This topic appeared to have been closed, but Ukrainian parliament has taken very long to approve the legislation regulating the reactor’s completion. Russia offered a state-guaranteed loan at a very low interest, however, when the parliament has finally passed the bill, they have suddenly drawn back and suggested to use one the commercial banks instead. That’s a typical Russian attitude – all talk and no action”, – explains Olga Kosharna. She is the head of the public relations at the Ukrainian nuclear industry professionals, “Ukrainian Nuclear Forum” and the member of the public council advising the State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine (SNRIU). Earlier in her career, Kosharna worked in the organisation herself.

Tyzhdenhad contacted Energoatom on this issue. According to Energoatom’s response, Russians and Koreans were competing in the final stage of the afore-mentioned tender. The former agreed to build two generators at the cost of USD 3.8 billion, while the latter offered a price of USD 4.5 billion. At the same time Koreans suggested to use empty grounds, initially intended for KhAES-5 and KhAES-6, to build KhAES-3 and KhAES-4, instead of using uncompleted Soviet construction frames. Additionally, overall costs of Korean generators would end up being lower as a result of reactor’s higher capacity.

Despite all this, the sole idea of KhAES-3 and KhAES-4’s completion did not anticipate high competition and Russians’ victory in the 2008 tender hardly came as a surprise.

RELATED ARTICLE: Nuclear arms in the hands of Russian leaders

Complete or build from scratch?

All 15 of the active reactors in Ukraine belong to the water-water energetic reactor (WWER), a type of pressurised water reactor originally designed in Soviet Union. Incidentally, Chornobyl NPP was using the other type of reactors, ‘high power channel-type reactor’ (RBMK), but after the plant was closed down in 2000, Ukraine has never been back to using these types of reactors. WWER is not a unique technology and has been occasionally presented by various nuclear equipment suppliers. For instance, ‘Westinghouse’ presented the AP-1000 generator at the 2008 tender, while the Korean company mentioned above, presented its KEPCO APR-1400 – both of these generators belonged to the same type as WWER. The digits in the name of these generators indicate its capacity in kilowatts. It is important to note that reactor is only a component of the very complex NPP. In 2008 Russians presented WWER-1000, the one that Ukrainians were already familiar with, since this type was used in 13 out of 15 currently active reactors. Unsurprisingly, since this was the only reactor type compatible with KhAES-3 and KhAES-4, it was clear from the beginning that the tender was a set up.

Nevertheless, the fate would not let Russian Atomstroyeskport implement KhAES-3 and KhAES-4 either. Permission to build new nuclear reactor may only be issued the Ukrainian parliament, and the relevant legislation was only passed in 2012. Two years later the war between Ukraine and Russian began and in 2015 the parliament decided to terminate agreement with the Russians. The current speaker of Ukrainian parliament, Andriy Parubiy, called this decision symbolic. Ukrainian nuclear scientists have not abandoned the hopes to complete the KhAES-3 and KhAES-4 projects and expressed eagerness to continue completion with different contractor.

Interest shown by the Ukrainian government and Energoatom in completion of the two afore-mentioned reactors, is easy to explain. Construction of a brand new reactor is a very costly undertaking and success is by no means guaranteed. Opponents of the project always refer to “Olkiluoto” nuclear power plant in Finland, which was commissioned to AREVA, a French contractor. The Finnish reactor was meant to turn a new page in the history of NPP – French were the first to introduce the new type of reactor, European Pressurised Reactor (EPR). However this venture ended up being an economic disaster. “Finnish EPR in Olkiluoto was meant to be the first reactor of the third generation – safe, accessible and evidently planned for the mass production. However, currently contractors are three years behind their initial plan, the budget had been exceed by billions of pounds after constructor had caused more than 3 thousands technical errors”, – commented Meirion Jones, the BBC journalist, in 2009. He was also critical of British government’s plans to build EPRs in the UK. The situation has not changed much over the past 10 years and the opening of Finnish generator is still being postponed. The last due date set was June 2019. Partially, the high costs of the new NPPs are explained by the high measures of safety, which were implemented after nuclear disasters at Chornobyl and Fukusima.

The era of the gigantic NPP is over, and even the people who work in the nuclear industry admit to that. “I think, that the completed third and the fourth generator at KhAES should be the last high power reactors ever built in Ukraine”, claimed Yuriy Nedashkovskyy, the chairman of Energoatom, during the meeting with students at OSA club. He has primarily quoted economic rationality as a main reason.

It is also economically unsustainable to rebuild KhAES-3 and KhAES-4 to work with the different types of a reactor, and there are little examples of such practice. One of them is Bushehr NPP in Iran. Here construction works were carried out by Siemens, German industrial manufacturing company, in 1970s, however as the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran was followed by immediate international sanctions, the project was eventually frozen. In 1990s it was reopened by Russians, who tried to adjust Russian WWER-1000 to German-built facilities, however the result turned out to be unprofitable.

Representatives of Energoatom claimed that if KhAES-3 and KhAES-4 were meant to be completed using any other reactors instead of WWER-1000, it would “lead to substantial additional costs”, if the Soviet construction framings were left unused. Apart from the need to clear up the space and deploy already present constructions, there are also logistics problems and the lack of new fuel providers. In case of WWER-1000, Energoatom promised to localize the ner’s cacapity in Ukraine on 60-70% level.

RELATED ARTICLE: Ukraine’s Status as a Non-Nuclear Weapon State: Past, Present and Future

The Czech company and the Russian sanctions

In July 2018 Ukrainian government, led by Volodymyr Groysman, approved revised technical plan for KhAES-3 and KhAES-4. Reactor, named in the bill was the WWER-1000 type. According to revised project budget, the overall costs of construction for both reactors would reach UAH 72 billion (approximately EUR 2.3 billion according to the current exchange rate). Thus, only one generator would end costing more than EUR 1 billion. This is 4 to 10 times cheaper than some of the analogue reactors discussed above. Even if the costs increase once the project progresses, it is still highly unlikely that it would reach the costs of the brand-new reactor. According to the Energoatom’s estimations, the cheapest new reactor operating on the low-cost Chinese HPR-1000 generator would end up costing UAH 160 billion (EUR 5.2 billion).

The lower costs are not the only advantage of continuing construction of KhAES-3 and KhAES-4. These projects are also closed tied to “Ukraine-EU Energy Bridge”, a project currently actively supported by the Ukrainian government. The main idea of the project is to start exporting Ukrainian energy from the KhAES’s second reactor to the EU countries using the “Khmelnytska NPP-Rzeszow (Poland)” power transmission lines. The revenues, anticipated by Energoatom, are planned to be used for the KhAES-3 and KhAES-4’s development. Additionally, participation of European partners in the project may also facilitate acquisition of loans necessary for construction.

However, one vital factor is obstructing this plan. In the current energy market, there are only two companies, which have an experience building the WWER-1000 reactors. These are Russian “Atomstroyeksport” and Czech “Skoda J.S.”. Czechs have earlier built similar reactor plant for their own Temelin NPP. Quoting the government’s technical strategy plan referenced above, “State Owned Enterprise Energoatom should only contract third parties in accordance to Ukrainian legal framework set to regulate current sanctions regime and the laws on state policy necessary to maintain Ukraine’s state sovereignty on temporary occupied territories in Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts”.

In other words, the government has made it clear – cooperation with Russians will not be welcome. The problem is, the ultimate beneficial owner of the Czech Skoda S.J. is Russian holding company, OMZ, also known as “United Heavy Machinery” or “Uralmash-Izhora Group”, which, in turn is ultimately controlled by Russian Gazprom. Both of these companies are currently subject to Ukrainian sanctions against Russia. While Skoda S.J. is not the subject to sanctions itself, it automatically de-facto becomes one, being a fully-owned subsidiary of the sanctioned entity, and Ukraine will face a choice – either hold off construction of KhAES-3 and KhAES-4, or include Russian-owned European subsidiary into the process.

“When I hear objections against the Russian money, I always reply, that Czech Republic is the member of the European Union and it does comply with the European laws. There is also European Atomic Energy Community (Euroatom), an organization which is supposed to exercise certain measures of restrain and control. Additionally, we buy the nuclear fuel from Russians. If we try to buy the fuel from Americans, we will create another monopoly, and we have already had this experience with Russians earlier on and we simply cannot afford to let this happen again. The circumstances forced us to buy the fuel from the Russians. Fuel is not a gas, it is a unique product and it is not possible to purchase it from European storing facilities. Of course, I agree, it’s a very sensitive topic”, – explains Olga Kosharna.

Iryna Golovko, a colleague of Kosharna in SNRIU, begs to differ. She is the head of the energy department of an NGO called “Ekodiya”. Golovko does not deny that her organisation would fully support the government’s potential decision to completely give up the nuclear and coal energy sources and employ renewable energy sources instead. Ekodiya is currently leading campaign aimed against completion of KhAES-3 and KhAES-4. One of the main problems, underlined by the activists – cooperation with the Russian-affiliated company. “WWER-1000 can only be built by two companies in the world. Atomstroyeksport and Skoda J.S. Nobody else has experience in leading these projects. How can we talk about energy independence if we are partnering with Russians again?”, – asks Golovko.

Energoatom denies that there is no alternative to Skoda J.S. Representatives of the company claim that the winner will be selected in accordance with Ukrainian tender laws. As one possible option they name Korean KEPCO, Chinese CNNC and Japanese Mitsubishi. However, Energoatom’s representatives agreed that this may put their plans on hold for at least next 8 years and cause significant cost increase.

Parliament’s decision

Strong presence of the Russia-affiliated companies is not the only problem underlined by the ecologists. Skoda J.S.’s involvement in the project has not been unanticipated. Specialists and representatives of ÚJV Řež, a. s., a Czech research institute specialising in security systems developed for nuclear reactors, had visited construction sites in Khmelnystk for inspection. Czechs suggested that Ukraine adopts newly developed security measures for WWER-1000 and applies them at the planned KhAES’s reactors. Interestingly enough, Skoda J.S. partially owns ÚJV Řež, a. s. (majority shares are, nevertheless, held by the big Czech state-owned energy company).

“Skoda J.S. suggested some additional safety measures, which, they claim, can already be implemented, despite the fact that none of the existent WWER-1000 reactors have tested these measures yet”, – says Golovko. Her opponents’ response is simple – only ultra-modern technologies are going to be used and it will only assist the project. Another worrying issue is the need for complex inspection of reactors’ frame construction, which has to be done after the final project is ratified. According to Golovko, Energoatom had already been holding tenders to find a contractor to supervise and inspect KhAES-3 and KhAES-4 framing. She insists that it has to be made clear that potential operating period of those two reactors may end up being much longer than initially anticipated in 1980s.

Several public hearings are set to be held across Ukraine, including the one in Kyiv, in relation to the reconstruction of KhAES’s reactors. Ukrainian parliament will nevertheless have the final say in the matter – and Ukrainian MPs will fully bear the responsibility for their decision. Disagreements surrounding the building of the two generators may only lead to further drawbacks in the energy industry in Ukraine. Government’s energy strategy anticipates deferring the exploitation of already built energy reactors – some of them for a period of up to 20 years.

According to the Energy Strategy bill, Ukraine will have oversupply of energy-generating facilities by 2025 and will face the need to renovate its existent facilities. Additionally, once most reactors are fully utilised by 2030, Ukraine will have to replace the whole generation of these facilities. Assuming that the official stance of Ukrainian government remains unchanged, this will be the time when the main battle between proponents and opponents of the nuclear energy will unfold. If reliance of nuclear energy prevails, Ukraine will have to think of a way to renounce its dependency on Russian technologies. Some steps in the right direction have already been made. In December Nedashkovskyy, Energoatom’s chairman, announced that KhAES-3 and KhAES-4 will be the last high-power channel-type reactors in Ukraine, and claimed that the future belongs to small modular reactors (SMR). This was an obvious gesture towards Holtec International, an American supplier of equipment and systems for the energy industry. Last year, in February 2018, Ukrainian and American companies signed an agreement to build an SMR-160 factory in Ukraine. Who knows – maybe by the mid-century they will replace the Soviet giants, which haven’t got much left.