Politicians and pundits across the world are looking wearily at the causes and possible implications of America’s withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty signed in December 1987 with the Soviet Union. A historian’s voice will be helpful in this context. As we look at the approach of Russian leaders, from Joseph Stalin to Vladimir Putin, to nuclear missiles, we can see the conclusions that will help us to understand the present situation better.

Stalin’s legacy

In August 1945, before the end of World War II, a committee on the development of nuclear weapons was established in Moscow. It reported to Joseph Stalin directly. In the spring of 1946, a similar body was launched to coordinate the development of missile equipment. In June 1947, the third committee emerged with a similar status. It worked on developing air and missile defence systems. Their demands were binding for ministries, government bodies, academic institutions and construction enterprises that employed millions of workers, engineers, civilian and military officials. While the rest of the country was struggling amidst the post-war devastations, these committees faced no material or financial limits.

The results of their work were quick to arrive. In 1949, the Soviet Union tested a nuclear bomb. In 1953, it tested a thermonuclear bomb. The soviet army enrolled the first complex equipped with the R-1 missile (range of 270km) in November 1950. A powerful ballistic missile plant was built in what had then been Dnipropetrovsk and is now Dnipro. Stalin did not get a chance to apply the nuclear missiles his country was developing for his geopolitical purposes. In March 1953, a dozen actors from his closest group ascended to power, while in June 1957, Nikita Khrushchev tried walking in Stalin’s shoes.

A superbombman

In May 1954, the soviet government decided to develop a missile to take a manmade satellite to the Space based on a report by scientist Sergei Korolev. The actual goal of this task was far from space exploration. Instead, the government decision spoke of the ability to “ensure that strategic targets can be hit in any military-geographic area of the globe.”

In October 1957, the Soviet Union launched the first satellite, while on April 12, 1961, Yuri Gagarin went on the first flight to Space. Agitation departments in the party committees of all scales presented this as evidence of what socialism was able to accomplish, how the Americans lagged in the space race, and how the decay of the capitalistic economy was to blame. Meanwhile, Khrushchev used these accomplishments to back his foreign policy assaults. After German Titov, the Soviet Union’s second astronaut, returned from Space, Khrushchev said at a reception in the Kremlin in August 1961 that “We don’t have bombs of 50 or 100 megatons, but we have a bomb of over 100 megatons. We sent Gagarin and Titov to Space, but we can replace them with other load and send it anywhere on Earth.” As he met every astronaut returning to Earth with celebrations, the First Secretary of the Communist Party Central Committee saw a superbomb rather than a human in them.

The construction of ballistic missiles in Dnipro was put on an industrial scale. In December 1959, the Strategic Missile Army was established and equipped with R-12 missiles designed by Mikhail Yangel. They could be permanently combat-ready in the shafts protected from air strikes.

“Train the population to expect a nuclear war”

Starting from the mid-1950s, soviet leaders began to establish personal contacts with the leaders of western countries. It created an illusion of the Kremlin’s dynamic foreign-policy course but did not deliver significant results. The first ever visit of a soviet leader to the US in September 1959 was fruitless. Khrushchev’s meeting with John F. Kennedy in June 1961 in Vienna was a failure too. The minutes published after the meeting showed that the soviet leader adopted quite an aggressive tone in his conversation with the young American president. The dialogue mostly focused on the German issue. Khrushchev claimed that he would sign a peace treaty with the German Democratic Republic unilaterally. This would mean that the Americans would no longer have access to West Berlin. At the same time, Khrushchev suggested that western leaders would not risk starting a war over this. As he claimed that the Soviet Union would not start one (after the Americans lose access to West Berlin), Khrushchev added with a note of demagoguery that “If you start a war over Berlin, it’s better that it happens now than later when more terrifying weapons emerge.”

RELATED ARTICLE: A reform that ruined the Soviet Union

This placed the responsibility for difficult decisions on the US president. The soviets expected Americans to tie the president’s arms out of fear. Nothing of the sort could happen in the Soviet Union. Khrushchev viewed soviet people as the population rather than as citizens. The protocol of the Communist Party Central Committee presidium meeting on July 1, 1962, has a section On Berlin. The attendees, including Khrushchev, Mikoyan, Gromyko, Kosygin, Brezhnev, Suslov and Ponomariov, were analysing ways to squeeze the troops of western countries out of West Berlin and the West’s possible reaction to those actions. “Train the population to expect a nuclear war” was the short sentence summing up the discussion.

This shows that Khrushchev saw the use of nuclear missiles as a possible option. The scary sentence in the meeting protocol confirmed that intention. In this case, it was not Khrushchev’s intent to blackmail the Americans. The sentence was in a top-secret file only for insiders on the very top of the Communist Party. Obviously, the availability of nuclear missiles in the Soviet Union could be further used to blackmail NATO leaders. The Kremlin’s powerholders were prepared for any scenario.

The Cuban Missile Crisis

By then time the statements on the inevitability of a nuclear war were recorded, Defence Minister Rodion Malinovsky was already finalizing the development of operation Anadyr upon instruction from Khrushchev and consent of Cuba’s Fidel Castro. This was about deploying 24 R-12 missiles and 16 R-14 missiles with nuclear warheads in Cuba, as well as 50,874 military and maintenance personnel.

Operation Anadyr caused a bad crisis between the US and the Soviet Union. The world spent a few days on the brink of a nuclear missile war in October 1962. Then the tension was eased when Kennedy stated that the US had no intention to take over Cuba. Khrushchev withdrew soviet missiles from the island. Following the crisis, a direct connection line was set up between the Kremlin and the White House. It played an important role in preventing international complications in the future.

Now known in every detail, the Cuban Missile Crisis shook the politicians that made fateful decisions back then. They got too close to the verge of complete darkness. Even Khrushchev and the people close to him probably no longer dared to tell themselves “Train the population to expect a nuclear war”. Uncontrolled arms race was leading the world into a dead end. US Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara was the first to speak about it publicly, claiming that the concept of implemented nuclear prevalence (“unacceptable damage”) had to be cast away and replaced with the concept of “strategic stability”. After lengthy preparations, the Ministries of Foreign Affairs of the US, UK and Soviet Union signed the Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water on August 5, 1963, in Moscow. It was open to be signed by the UN member-states that wished to do so.

The next step was to sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons developed by the UN Disarmament Commission. Aimed at preventing the expansion of states with nuclear weapons, it was adopted by the UN General Assembly on June 1, 1968. The Treaty recognized five UN Security Council member-states, including the Soviet Union, USA, UK, France and China, as countries that have nuclear weapons. They agreed to not transfer it to non-nuclear-weapon states, nor support or encourage them to obtain it. In July 1947, the Soviet Union and USA signed the Treaty on the Limitation of Underground Nuclear Weapon Tests.

Looking for a balance

Willy Brandt’s Ostpolitik seriously softened tensions in Europe. In August 1970, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a treaty refusing to use force against each other. West Germany recognized the post-war borders in Europe, including the border between the German Democratic Republic and Poland. West Germany and Poland signed a treaty to recognize the German-Polish border, too. Four powers, including the UK, the US, France and the Soviet Union, signed an agreement on West Berlin guaranteeing free access to this enclave. Finally, both parts of Germany recognized each other and established diplomatic relations.

The American-Chinese solution initiated by US President Richard Nixon was followed by the emergence of a new geopolitical situation. Therefore, soviet leaders responded positively to the signals which the US President sent both to China and to the Soviet Union. In May 1972, Nixon flew to Moscow and signed the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT-I) on the levels agreed by the moment of the signing. In June 1979, SALT-II was signed at the meeting between Leonid Brezhnev and Jimmy Carter in Vienna. It limited the number of strategic nuclear warhead carriers to 2,400 pieces. The US Congress did not ratify the treaty after the soviet army invaded Afghanistan. But the sides complied with the restrictions it set out up until the treaty expired in December 1985.

As the tools to deliver nuclear weapons evolved, they prompted the need for new treaties between the the two superpowers. Since SALT-II did not retulate restrictions on the deployment of surface-to-surface ballistic and cruise missiles with the range of 1,000-5,500 km and 500-1,000 km. Not counting on goodwill of the soviet leaders, America’s politicians were willing to spend dozens of billions of dollars for the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) that had to protect the US from an intercontinental missile attack.

Dubbed by journalists and subsequently better known as Star Wars, SDI built on innovative space technologies. America’s new president Ronald Reagan called the Soviet Union “evil empire” and was successful in creating a united anti-soviet front with NATO countries and China.

Three meetings between Reagan and Gorbachev between 1985 and 1987 were followed by a treaty on the liquidation of intermediate and short-range nuclear missiles. The Soviet Union committed to dismantling and destroying the entire class of these missiles. The US undertook similar commitments. That radical decision taken in December 1987 seriously contributed to the easing of the confrontation in the most important dimension of the Soviet-American relations.

In May 1988, the withdrawal of soviet troops from Afghanistan began. Mikhail Gorbachev supported the military operation by the US and other countries against Iraq which tried to take over Kuwait. In September 1989, the wall dividing West Berlin and the capital of the German Democratic Republic lost its functional role and turned into a relic of the epoch that was rapidly moving into the past. On September 12, 1990, a treaty was signed in Moscow to finalize the solution of the German issue between representatives of the US, UK, France, Soviet Union, West Germany and East Germany, allowing the German nation to reunite. Berlin became the capital of Germany. The Cold War was over and the Yalta Europe seized to exist.

All this led to the signing of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START-I) between the Soviet Union and the US. Signed on July 31, 1989, at the meeting of Mikhail Gorbachev and George Bush, it set equal limits on the number of warheads and delivery tools for both countries.

When the Soviet Union collapsed and ballistic missiles emerged where the main part divided into multiple independent missiles with nuclear warheads, a new treaty was necessary. START-II appeared in January 1993 when Boris Yeltsin met with George H. W. Bush in Moscow. The document banned the use of multiple independently targetable vehicles on intercontinental ballistic missiles.

A tool of blackmail

When the Russian operation to seize Crimea was in full swing in March 2014, Vladimir Putin met with journalists and assured them that his country had nothing to do with the developments in the peninsula. A year later, on March 15, 2015, Russiya 1 TV channel screened what it referred to as a documentary titled Crimea. The Path to Homeland. The peninsula was annexed, the Russian society happily welcomed that development and Russian media were extremely successful in fueling hatred against the Ukrainian people which had until recently been considered a “brotherly nation”. It was no longer convenient for the Russian leadership to keep its contribution to the annexation of Crimea secret. Therefore, Putin spoke openly to film director Andrei Kondrashov. “As to our nuclear deterrence forces, we were ready to transfer them into full battle readiness,” he said, among other things. “I spoke to colleagues (leaders of Western countries – Ed.) and told them that Crimea is our historical territory, that Russian people live there and they are in danger, and we could not abandon them.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Elections and the Great Terror

Before that statement, Russian radio and TV journalists had for a year been echoing the “radioactive desert” phrase, implying that NATO member-states would turn into a “radioactive desert” if they tried to interfere with Russia’s takeover of Crimea. Long influenced by the Kremlin’s policy defined in the sentence of “training the population to expect a nuclear war”, the Russian people were not afraid to hear the “radioactive desert” phrase. That is the most unsettling thing to know.

Having the support of their people, the leaders of modern Russia annexed Crimea in blatant violation of the Atlantic Charter declared by Roosevelt and Churchill on August 14, 1941. The document established the postwar world order based on three principles: territorial integrity, non-use of force in international relations, and creation of collective security. On January 1, 1942, the 26 countries that fought against Hitler-led Germany and its allies supported the Atlantic Charter, signing the document as United Nations. Dozens of countries were created and fell apart over the next seven decades. But no country was successful in seizing part of another’s territory using its military prevalence despite some attempts, such as Iraq`s attempt in Kuwait.

The annexation of Crimea was conducted by the leadership of a state with nuclear weapons and a veto in the UN Security Council. Putin’s thinking that these two factors make him unaccountable under international law is wrong.

“We will get to paradise as martyrs”

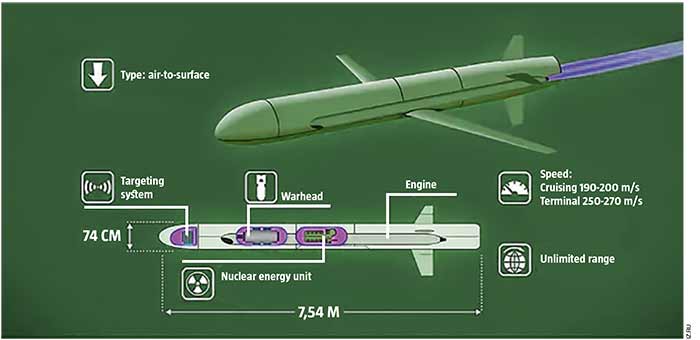

Signed in December 1987, the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) began to be diluted by the progress in the production of tactical missiles. In 2017, Novator, an air-to-air equivalent of the Kalibr surface missile that did not fall under the INF, appeared. Russia deployed it in its European part. Iskander-M tactical missiles with the range of over 500 kilometers were found in Kaliningrad Oblast and the occupied Crimea. On October 2, 2018, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg officially stated that Russia was not complying with its commitments under INF.

Putin’s reaction was similar to Khrushchev’s response in the Cuban Missile Crisis. When speaking at the Valdai club on October 18, he assured the audience that “Our concept of nuclear arms use does not envisage a preventive strike. Our concept is a response to a strike.” Then he immediately referred to the Kremlin’s talking point of an inevitable nuclear missile war. “An aggressor must know that payback is inevitable, it will be destroyed in any case. We are a victim of aggression, we will get to paradise as martyrs and they will simply die because they will not even have time to repent,” he said. Interestingly enough, a former Cheka officer added a new religious dimension to this long-present soviet statement.

On October 20, Donald Trump declared the US’ intention to withdraw from the INF which Russia violates on a regular basis. European member-states of NATO insist that America’s president should try to convince Russia to stick to the document because the whole of Europe is within the reach of Russia’s intermediate and short range missiles. NATO ministers of defense are to meet for talks on this in Brussels this December.

Time will show how things develop. One thing that is clear now is that the Putin-led Russia is training its population to expect an inevitable nuclear war while blackmailing other countries with its nuclear missiles to accomplish its aggressive goals. Whatever treaties prescribe, an aggressor should be put within certain limits via other means, such as the development of defense capabilities.

Translated by Anna Korbut

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook