The recent foreign debt saga and the looming sovereign default stole all spotlight from a series of news that may turn out to be far more important in the long run.

Crucial facts

On July 16, Agro Holdings (Ukraine) Limited, a company owned by the US-based NCH Capital, acquired 100% of Astra Bank that had been announced insolvent in March 2015. By August 13, Astra Bank received cash injections needed to bring its capital adequacy and liquidity back to normal.

On August 7, Primestar Energy FZE, a UAE-based company that is part of the Primestar group, bought 100% of UkrGazPromBank deemed insolvent in early April 2015.

On August 13, Finansy i Kredyt, one of Ukraine’s biggest banks that was put on the problem bank list in spring, registered an issue of additional securities worth slightly under UAH 2bn. According to Ukraine’s central bank, NBU, other biggest banks have also met recapitalization requirements.

RELATED ARTICLE: Government plans for public property management reform and upcoming privatization

In early August, UniCredit group announced transfer of control over UkrSotsBank to Alfa-Bank for a stake in ABH Holdings SA, the manager of Alfa Group’s banking assets. The merger of UkrSotsBank and Alfa-Bank will create the fourth biggest credit corporation in Ukraine. At the end of August, the Deposit Guarantee fund announced a purchase of 100% of PBC, a bank in transition established on the basis of the insolvent Omega Bank, by the Ukrainian Business Group.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) intends to acquire 35% of Reiffeisen Bank Aval’s shares from the additional issue scheduled for October. The decision was taken on July 23.

News of the mergers and acquisitions of Ukrainian banks are only emerging in the media, but it is obvious that they are the early signals of a wide-scale process that will have a serious impact on Ukraine’s banking system.

Banks in retrospect

Ukraine saw two major waves of bank mergers and acquisitions over its recent history. The first one took place before the 2008-2009 global financial crisis. Stakes in Ukrainian banks were mostly acquired by non-residents who hoped that Ukraine’s economy and banking system would soon begin to grow rapidly and had cheap cash to bring to Ukraine and lend out. The owners were willing to sell banks because they were offered good prices, and they were aware of the low quality of their assets, but preferred to keep investors uninformed of that. At that point, Ukraine’s banking system was a market of sellers: investors would buy banks at prices that were five to seven times above their actual value.

RELATED ARTICLE: Proposals for tax reform

The second spate came under the Yanukovych regime and was of a completely different nature. Bank owners, mostly foreigners by now, no longer believed that the banking sector and economy overall had any prospects in Ukraine under the then government. They were fleeing the country and selling assets to Ukrainian businessmen close to the government. These new buyers had much better prospects thanks to friends in power. That was the market of buyers who paid 0.5-1.0 of the bank’s capital worth for an institution. After the regime collapsed and Ukraine tumbled into a full-scale financial and economic crisis, mergers and acquisitions of banks virtually stopped. The owners were struggling to clean up the mess they had on their hands and keep what they had afloat. Potential buyers saw no sense in acquiring credit facilities with unattractive balance sheets and obscure prospects operating in an extremely difficult environment.

The fact that mergers and acquisitions resume in Ukraine’s banking sector signals that there is a number of agents (buyers) who see good prospects in the country’s economy and financial sector, or believe that benefits are far more likely than the risk of continued recession and bankruptcies. Confident of seeing the light at the end of the tunnel, they want to do deals quickly, before economic revival becomes obvious and the assets go up in price. There is also another category of agents (sellers) who do not believe in Ukraine’s prospects overall, or in the short run. As a result, the market for mergers and acquisition has acquired some balance, even if as fragile as Ukraine’s economic balance achieved recently.

Drivers of foreign interest

Foreign investors still have different motives for acquiring banks in Ukraine. NCH Capital intends to create a bank focusing on lending to agribusiness. The company has been working with agriculture in Ukraine for many years. It now hopes to benefit from a synergy of expertise it has accumulated and the bank it just acquired. The Ukrainian Week’s sources claim that NCH has long been looking for a bank to buy in Ukraine but was asked exorbitant prices under Yanukovych. Now, it sees a good opportunity to implement its plans at minimal cost. The management board headquartered in New York eyes the deal with a lot of skepticism but relies on the Kyiv office managers for this decision so far. It is to be seen how well the local team copes with the task. However, the move is undoubtedly well-justified.

The UAE investors’ deal with UkrGazPromBank is less straightforward. Many experts doubt that Primestar Energy FZE is the ultimate beneficiary of the newly-acquired bank. The company may well be acting in the interests of people who are much closer to Ukraine than the residents of the UAE. On the other hand, Arabic investors are flush with cash accumulated over the period of high oil prices. Primestar Energy FZE is in the oil trade business itself. It may be looking to acquire depreciated assets in countries like the post-crisis Ukraine since projects elsewhere are far more expensive. Moreover, Arab investors have already shown interest in the privatization campaign the Government is preparing in Ukraine.

RELATED ARTICLE: Positive and negative results of austerity and painful economic reforms

The EBRD’s motivation is clear. It is part of the pool of Ukraine’s financial donors. Therefore, its move to acquire the bank in Ukraine provides the much-needed support to the country and sends a strong positive message that Ukraine’s economy and finance are past the most dangerous stretch to the global business community. EBRD representatives have actually stated their intention to send out such a signal.

The motives of the Russian Alfa Group are quite straightforward. The Russians have been expanding into the Ukrainian financial market strategically, and crises play into their hands by helping them increase their presence at minimal cost. The pattern was similar in 2008-2009 and remains unchanged today. The only difference now is that Russia is an aggressor state.

Signaling optimism

All these deals have a number of things in common. Firstly, non-residents assume that FX risks are acceptable, i.e. further devaluation of the hryvnia is unlikely. If they assumed otherwise, the deals would hardly take place: non-residents could wait out a bit more and get the same banks for less money. This definitely sends a positive signal to Ukrainians.

Secondly, foreigners believe that Ukraine’s banking sector has passed its worst period in terms of bankruptcy risks. It is one thing when NBU chair claims that the clean-up of the banking sector is completed: theoretically, Valeria Hontareva can say this to calm down Ukrainians. It is something altogether different when a non-resident decides to invest capital in a Ukrainian bank. Clearly, such a decision sends a positive signal not only to other investors, but to average Ukrainians, too. When an asset hunt begins, the balance of payments improves, the economy fills with cash and starts to grow.

Secondly, foreigners believe that Ukraine’s banking sector has passed its worst period in terms of bankruptcy risks. It is one thing when NBU chair claims that the clean-up of the banking sector is completed: theoretically, Valeria Hontareva can say this to calm down Ukrainians. It is something altogether different when a non-resident decides to invest capital in a Ukrainian bank. Clearly, such a decision sends a positive signal not only to other investors, but to average Ukrainians, too. When an asset hunt begins, the balance of payments improves, the economy fills with cash and starts to grow.

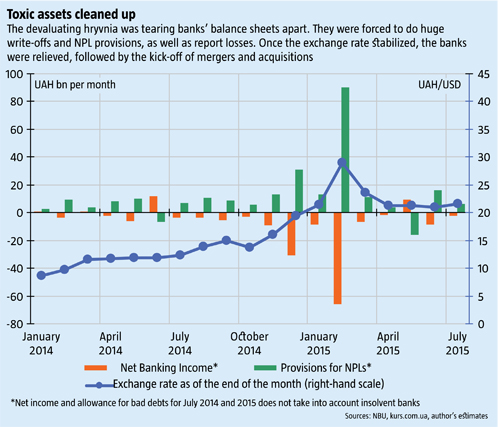

Thirdly, non-residents are confident that most of the ballast of the past years has been cleaned up. They are probably right about this. Write-offs and allocations to reserves for bad debts have peaked already, losses are accounted for. According to the NBU, total allocations to reserves for bad debts over the period from January 2014 to June 2015 amounted to UAH 222bn or over 17% of assets as of early 2014. In short, balance sheets have been cleared of all assets that had to be written off, so they now reflect the real status of banks far better than they used to and can thus be reliable indicators for a purchase. For Ukrainians, this means mass bankruptcies of banks and loss of deposits are over. Of course, some banks can still go broke, but people can now largely return to depositing their savings.

Would it not be easier to establish a new bank rather than pay for assets with an obscure balance sheet? The answer is simple: an established bank can be acquired for a sum worth half its capital and less. With it will come client base, market share, established network and a trained team. This will save investors time and money. The only risk is that banks still have residue toxic assets on their sheets after the clean-up. Since non-residents acquire banks, not merge with them, they obviously believe that the scales of write-offs reflect the amounts of remaining toxic assets. Skeptics may say that foreigners don’t know the specifics of the local market and can be mistaken about the prospects of Ukraine’s economy. However, NCH Capital, EBRD and Alfa Bank have operated in Ukraine for a long time and are very well aware of the local specifics. The fact that Ukrainian shareholders have acquired Omega Bank is evidence that local capitalists are also optimistic.

Tips for the NBU

Acquisitions of Ukrainian banks by foreign investors will benefit Ukraine: it brings in the badly needed foreign currency. Therefore, the NBU should support this wave to a certain extent and with specific recipients, and it has plenty of room to do so given two aspects.

Firstly, most Ukrainian-owned banks were until recently used as pocket banks. They took in deposits from people and lent the money to the projects of their owners. Whenever a bank was sold, all loans issued to the founder’s entities were left hanging in the air. Forum Bank was the most telling example. At a certain point, loans to the companies of his founder Leonid Yurushev reportedly amounted to half of the bank’s loan portfolio. When the bank was sold to Commerzbank before the 2008-2009 crisis, the German investor had to do huge write-offs for the next couple of years because the recipients of the loans would not pay them back. Eventually, it failed to clean up the bank’s balance sheet and sold it to oligarch Vadym Novinsky for peanuts in 2012.

Similar cases were many. With each, Ukraine lost another bit of reputation in the eyes of foreign investors. To stop this practice, the NBU decided to restrict the share of loans issued to affiliated entities legislatively. The central bank should complete this initiative. Ukrainian banks will then have an environment that will dictate them a different quality of operation. That will make them more attractive to foreign investors.

RELATED ARTICLE: IMF Resident Representative Jerome Vacher discusses the review mission and assessments of Ukraine's economic situation

Another aspect is criminal background of the capital used to found banks. Until recently, anyone who had previously earned several million dollars could set up an own bank. Many did so to launder criminal money and earn a pretty penny on helping others do so. Bank managers were often non-professionals. That caused huge risk management problems, particularly for depositors who often ended up losing their money. Whenever that happened, bank owners would get refinancing, siphon off capital and leave Ukraine to avoid responsibility and abandon defrauded depositors at the mercy of the government.

Now, the NBU should take every effort to shut out such practices in the future. Banks should be owned and run by professionals with impeccable reputation and years of experience. One way to accomplish this could be to radically raise capital requirements for banks. If current owners do not have necessary cash for recapitalization and can’t draw it because of imperfect reputation, they will sell their assets to owners that are more transparent and professional. This will create an environment where Ukrainians will trust banks more. This will also benefit the country’s financial sector by pushing small banks to consolidate into big ones that are more stable and prepared for foreign investors.

Therefore, the unfolding series of bank mergers and acquisitions sends many good signals and gives reasons for optimism. The government should seize the opportunity to increase trust for banks, draw foreign investment and make banks more transparent – and depositors happier.