Ganna Fabre, a French-Ukrainian translator and editor, was born in Kharkiv. In this reflective piece, she offers her impressions of her hometown—a city scarred by war yet unbowed, its spirit nurtured and upheld by its resilient inhabitants.

Amidst the turmoil of war, Kharkiv has embraced the motto “Kharkiv is a reinforced concrete” (‘zalizobeton’ in Ukrainian), a powerful expression of its resilience and a nod to the city’s rich architectural legacy, where the vibrant spirit of 1920s constructivism can still be felt in its striking concrete structures.

However, by the summer of 2024, Kharkiv is shrouded in an unsettling anxiety. The sudden and unexpected Russian offensive in May sent shockwaves through the city, leaving residents reeling and deeply unsettled. After the Ukrainian counteroffensive and the liberation of parts of the region in the fall of 2022, a fragile sense of security had begun to take root, bolstered by announcements of defensive lines being erected along the border. Yet, it has become increasingly clear that these defences were either hastily built, poorly maintained, or entirely nonexistent. Were funds misallocated, insufficient, or simply siphoned off? These urgent questions weigh heavily on the community as authorities struggle to provide any sense of clarity amidst the chaos.

The Ukrainian army is determined to push back Russian forces along the Kharkiv front, with a particular focus on retaining control of the towns of Vovchansk, home to approximately 17,000 residents in 2019, and Lyptsi, situated to the north of the city. In the early hours of the war, several villages along the border fell under occupation, escaping the ravages of bombing until their liberation in the fall of 2022. However, with the onset of the second Russian offensive, relentless shelling has become a near-daily occurrence. Yet, against all odds, Vovchansk remains standing.

The mass exodus from this region has dramatically transformed the landscape of Kharkiv, now the closest refuge for those fleeing the war. Many residents have left behind not only their homes but also beloved animals and small farms, forever altering the fabric of their lives.

My sister-in-law hails from a region close to the Russian border. On February 24, 2022, her older sister woke her in the early hours of the morning, urgently saying, “They’re here.” Together with her husband and their 12-year-old son, she endured the first nine months under occupation, grappling with severe shortages of electricity, water, and internet access as Russian forces destroyed cell towers. For another year, they lived under constant bombardment.

Eventually, they made the difficult decision to leave their village. First, they took their son to Poltava, roughly 200 kilometres away, to stay with their eldest son. They returned to the village regularly to care for their animals. Days blended into one another, marked by the absence of electricity and water, punctuated only by the sounds of Russian shelling. Once a week, Olga would trek up a nearby hill to find a signal, allowing her to call her sister and provide a grim update: this house had been destroyed, another had lost its roof. “And when are you leaving?” my sister-in-law would ask, a question that lingered unanswered for far too long. It wasn’t until September 2023 that Olga made her way to Kharkiv. Her husband remained in the village, joining her only in January 2024.

It’s not easy for the residents of agricultural areas to leave their homes, as their house (along with all the buildings and the farm) is the fruit of their labour; it’s their life. Leaving everything behind means losing not only their sources of income but also years of hard work. To leave is to abandon the land, to leave the animals. Despite the danger, some refuse to leave the animals in the villages. They then have to face the difficult decision to sell them, which means transporting them, in suitable vehicles, from a village under bombardment. Before that, they need to find a buyer and negotiate with them. All of this happens under constant stress.

Leaving also means arriving somewhere… But where? With whom? Maybe with a family member, if you still have family in Kharkiv (as was the case for Olga, who stayed with us for weeks). But eventually, you need to find a job and a place to live. You’re over fifty, you’ve arrived in a city where you know only one person… How much of a chance do you think you have to make it?

Olga and her husband successfully sold their dairy cow farm, marking a significant turning point in their lives. With determination, she secured a job, and within a few months, they found a place to live. Olga made the journey to Poltava to bring her son home, while her husband eventually found work as well. Until the second offensive in May 2024, they made weekly trips back every Saturday to check on their house and feed the dog they were unable to bring with them to their new apartment.

However, since the Russian offensive, returning to their village has become impossible. They remain uncertain about the fate of their home—already stripped of its windows—or whether their beloved dog is still alive, having been left to roam freely. Yet, every Saturday without fail, they continue to travel as close to their village as they can, seeking solace in conversations with Ukrainian soldiers, yearning to remain connected to their land, and nurturing a flicker of hope.

For Olga, the need to breathe in peace has become increasingly vital. Her brother left his village near Vovchansk in May 2024, and my sister-in-law managed to secure a small apartment for him and his partner—on the seventh floor. Serhiy recounts that when he first stepped out onto the balcony for a smoke, tears streamed down his face. “You understand, the seventh floor! I’ve always lived in a one-storey house… Lived,” he corrects himself, his voice heavy with emotion.

The uprooting and displacement of individuals from their villages have not been without profound consequences. In the short term, it presents an unprecedented emotional shock wrought by the war. In the long term, it is destined to inflict even more serious damage. Will the residents of the ravaged villages ever be able to return home? Likely not. For the time being, they find refuge in student dormitories that have been vacated by those who fled the city. Yet, can the authorities provide anything more substantial than this temporary accommodation? Probably not. The displaced have little choice but to take initiative, seeking solutions independently as they strive to forge ahead. They move forward, buoyed by a network of friends, acquaintances, and acts of goodwill, with family ties at the forefront.

Family bonds have withstood many trials since the onset of the war. Families have been fragmented, with women and children departing for foreign shores, leaving many couples unable to endure the strain of enforced separation. Some families wait anxiously for their men to return from the front lines, while others mourn their losses and attempt to rebuild their lives as best they can.

Despite the looming air raid alerts, the city of Kharkiv continues to embrace new arrivals. Since May, these alerts have become increasingly prolonged, with the longest stretching a staggering 38 hours and 16 minutes on July 21. In fact, there are now only a handful of moments each day devoid of sirens. This persistent state of alarm has hampered the functioning of numerous institutions, prompting banks, large shopping centres, and administrative offices to close at the first sound of an alert.

Nonetheless, newcomers are discovering, often with a sense of wonder, the city’s central square, its imposing university, pristine parks, lively markets, and a transport system that now operates on a war-time schedule. They can be easily identified as they tend to move in groups—be it families or friends—parents clutching their children’s hands with a firm grip. Frequently, they pause to read the commemorative plaques lining the main street, which remains largely deserted at ten in the morning, coming alive only in the evening as people finish their workday.

Following the initial welcome, Kharkiv faces a pressing challenge: the integration of its new residents. Schoolchildren must be enrolled in institutions that have been operating remotely since the onset of the invasion, and accommodations need to be made for the influx of high school and college graduates.

With limited spots available in secondary schools, vocational institutions are stepping in to fill the gap. However, the question remains: how can one effectively learn a trade in a remote environment?

After two years of Covid, schools reopened from September 2021 until February 23, 2022. In that time, students endured nearly four years of continuous remote learning. The dedication of our elementary teachers, middle and high school educators, university professors, and all educational staff has been nothing short of remarkable. They have persisted in teaching online and providing vital support to children and their families. However, this approach to education is not meant to be sustainable, and the resulting lack of social interaction and practical experience in various fields poses considerable challenges.

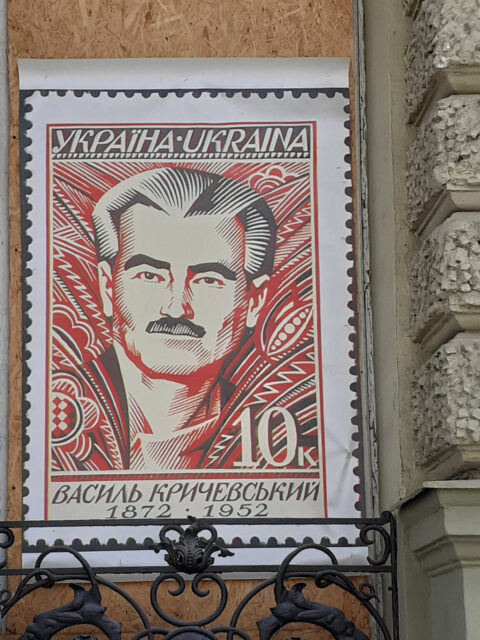

Moreover, both new and long-standing residents of the city require enhanced cultural spaces. Nearly all museums are closed, and the cultural landscape consists primarily of a handful of temporary exhibitions. One notable exhibition, launched in July 2023, focuses on the toponymy of Kharkiv. In line with Ukraine’s decolonisation efforts, street renaming initiatives are underway across the country. Thanks to the persistence of various associations and civil society figures, the municipality announced a new wave of renaming on July 26.

The “Proper Names” exhibition at the Kharkiv Literary Museum truly shows how important it is to rethink the names of places in the city. It points out the need to clean up Kharkiv’s visual landscape while emphasising the importance of connecting our history to these geographical markers. The war has forced us to rethink what we mean by “tolerance,” which often turned out to be a troubling denial of the realities we were facing.

How could we have dwelled in a city where the streets served as reminders of our colonial past? Prior to the full-scale Russian invasion, the presence of Bielinski Street—named after the Russian literary critic and revolutionary—seemed innocuous. We regarded it as merely a facet of our history, believing that history, in all its complexity, could not be altered. Yet, we possess the agency to choose which aspects of our past we wish to embrace. Do we truly wish to inherit the legacy of the Russian Empire, where Bielinski dismissed Ukraine’s right to exist and systematically belittled Ukrainian literature?

The authorities were slow to respond to the demands of civil society, which had been voiced long before the onset of the war. They consistently downplayed the importance of such concerns, arguing that there were more pressing matters at hand and that the timing was inappropriate for such discussions. In contrast, the residents of Kharkiv have decisively chosen the future they aspire to—a vision articulated by Ukrainian artists like Maïk Johansen, Mykhal Semenko, Alla Gorska, and Oleksandr Oles, whose legacies have long been overshadowed by figures like Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky in our collective consciousness.

In France, the movement to de-Russify Ukrainian culture frequently encounters resistance, as we are conditioned to “be tolerant” and “consider both sides.” I have personally attempted to embody this mindset, but to no avail. For me, erasing all remnants of Russian influence from my past serves as a tribute to the generations that fought for Ukraine’s independence.

Undoubtedly, there are residents of Kharkiv who staunchly oppose the notion of Ukraine as a sovereign state, even while residing within its borders. The most outspoken among them engage in acts of terrorism—transmitting strategic information to the Russian military, vandalising military vehicles, and disparaging our history and culture—resulting in their regular arrest and conviction. Others harbour anti-Ukrainian sentiments in their private lives. I find myself at a loss when confronted by a woman shouting on her phone in the street, “Do you understand they renamed Friendship of Peoples Street? What was wrong with that name?”

Nonetheless, I believe it is imperative to revitalise popular education and foster dialogue with such individuals. We cannot allow them to remain mired in ignorance, which only fuels their hatred. I would welcome the opportunity to discuss with her the notion of this “friendship of peoples,” which has resulted in the deaths of millions within the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. But is it worth investing politically and emotionally in the re-education of a generation that has failed to comprehend the burdensome legacy of these nations? Is this endeavour a lost cause? Once again, we find ourselves grappling with the question of education.

Another pressing issue facing Kharkiv today is the exodus of students. Higher education institutions are grappling with significant challenges, characterised by a decline in applications on one hand and a governmental reduction in the projected demand for specialists on the other. At Kharkiv National University, for instance, the Faculty of Arts boasted 100 first-year students in 1993, focusing solely on Ukrainian language and literature. By 2023, that number had dwindled to a mere thirty across five specialisations. The question looms: how many will enrol in 2024?

Many families are departing the city, driven by the reality of schools operating solely online and growing concerns about post-secondary education. My young nephew’s best friend is heading to Poland for his final year of high school to learn the language, with plans to return for university. The war is not just fracturing friendships; it is reshaping lives in the cruelest manner by stripping individuals of the freedom to choose their paths.

Yet, amidst these challenges, Kharkiv persists and even flourishes; the city continues to read. Since the onset of the war, at least three new bookstores have opened their doors, and Kharkiv, as the capital of printing, is home to more than a dozen publishing houses. Despite the recent strike on Factor Druk, one of the nation’s primary printing houses, the industry remains resilient, and booksellers continue to operate amid power outages and incessant air raid alerts. Are books expensive? I often feel uneasy when asked about the living standards of Ukrainians, particularly as I struggle to ascertain whether a specific product is deemed costly.

I am trying to establish benchmarks that render reality more comprehensible. On the regional website, the highest-paying professions reveal a stark economic landscape: a rehabilitation nurse earns a monthly salary of 50,000 hryvnias (approximately €1,100 at today’s exchange rate), followed by drivers at 27,000, management controllers at 21,000, accountants at 20,000, electricians at 19,000, mechanic-repairers at 18,000, and secondary school teachers at 16,000. To put this into perspective, a book priced at 400 hryvnias carries twice the weight in the budget of a Ukrainian teacher compared to its equivalent in France. In Kharkiv, a shared taxi ride costs 20 hryvnias (public transport is free), a bunch of parsley also costs 20 hryvnias, while a kilogram of tomatoes ranges from 20 to 50. A loaf of bread is priced at 16 hryvnias.

Amidst these economic realities, libraries invigorate cultural life, drawing readers in search of new literary works and meaningful human connections. The library at the National University of Kharkiv is open daily from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. The reading room, though sparsely populated, offers a sanctuary for the few who venture in. The librarians diligently manage cataloguing, and I relish the opportunity to hunt for old or rare titles alongside them. Each time they present me with a book for my research, I feel as exhilarated as if I were unwrapping a Christmas gift.

The Korolenko Library, the largest in the city, has taken the remarkable step of establishing a lending system—a first for this research institution. Currently, only one reading room operates on Tuesdays and Thursdays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. For those unable to work in the space, select titles can be borrowed for home reading.

As I step into this library, a familiar haunt from my student days, I am struck by a wave of nostalgia. While nothing has fundamentally changed, the entrance hall feels unrecognisably empty. I approach the front desk to renew my library card. The librarian greets me warmly, guiding me to the catalogue room.

“Would you like to consult the works in Russian?” she inquires, gesturing invitingly toward the shelves.

“No, I’m here for Ukrainian literature,” I respond, the emphasis on my heritage palpable in the air.

The question of language in Kharkiv remains unresolved as students, artists, and long-time residents depart while newcomers arrive. Many of the city’s current inhabitants navigate both languages, adapting their speech to fit the context. In 2023, a survey conducted among 1,433 members of the educational community—including 705 high school students across sixteen municipalities in the region—revealed that only 10 to 11 per cent of high school students in villages use Ukrainian outside school hours, while a mere 6 to 7 per cent of their urban counterparts do the same. Yet, an overwhelming 84 per cent still identify it as their native tongue.

This linguistic dilemma is deeply personal. I converse in Ukrainian with my older nephew, who has refrained from speaking Russian since the onset of the war, while my seventeen-year-old younger nephew and I communicate in Russian. The war has triggered distinct responses in each of them. For the elder, his rejection of the Russian language is a powerful act of resistance; for the younger, Ukrainian evokes the war, while Russian remains tethered to a world that existed before. As Kharkiv poetess Natalia Maryntchak aptly observes, “Everyone has their own war.”

I hold a deep admiration for those who have chosen to remain in Kharkiv, individuals whose resilience ensures that the city continues to thrive. They work, consume, and sustain the local economy, all while facing the reality of being living targets. The very fabric of the city endures because of these steadfast residents; one can only speculate on the depths of devastation the Russians would have inflicted had they been left unopposed.

Just like its residents, Kharkiv is undergoing a vibrant transformation, driven by the tireless efforts of municipal workers. Colourful flowers bloom throughout the city, lovingly tended to, while Shevchenko Park boasts picturesque pathways that invite leisurely strolls. The level of cleanliness is truly impressive—Kharkiv locals take great pride in their surroundings, diligently following civic norms. Pedestrians patiently wait for red lights, and cars glide by in an orderly fashion. In this carefully curated atmosphere, it feels as if time itself has paused, allowing the beauty of the city to shine through.

The walls of the city tell a story, adorned with portraits of Ukrainian artists gazing solemnly at passersby from plaques that have replaced shattered windows. Urban artist Hamlet’s graffiti offers words of encouragement to the city’s residents, and each visit reveals a new piece of art. This summer, along a street with a poignantly symbolic name—“The One That Brings Peace” (Myronositska)—I encountered a particularly meaningful work. Amid the power outages of 2023, when keeping phones charged and having an external battery known as a “power bank” became essential, the artist’s message resonated deeply: “You can be a power bank for others.” This spirit of communal support embodies the very essence of the people of Kharkiv.