Derzhstat, Ukraine’s statistics bureau, reports that annual inflation slowed down to 3.2% in January. At first glance, this looks like good news. It’s been a long time since prices grew so slowly in Ukraine, and that not very often. Right now, the inflation rate is below that of many developed economies, including China, Brazil and Mexico. Meanwhile, Ukrainians are seeing their disposable income increase, making them feel wealthier as prices stabilize. Those with deposits at banks are also enjoying watching relatively high interest rates against low inflation and a strong hryvnia boost value.

But this is just one side of the coin – pleasant for many, yet superficial and fleeting. When looked at comprehensively, the situation reveals a slew of serious problems in Ukraine’s economy and the way it’s being managed behind the attractive façade of the low inflation rate.

Talking about prices

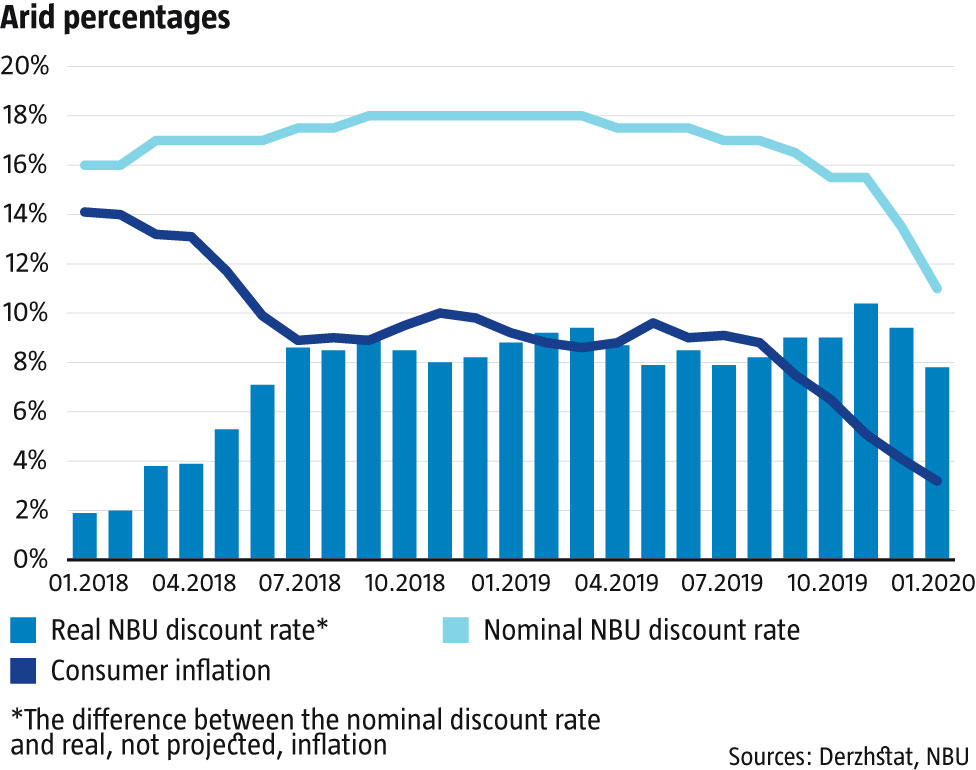

In 2019, many complained that the dollar was going down and prices were not. In September 2019, when the exchange rate was UAH 25 to the dollar, annual inflation began to really slow down (see Arid percentages), but prices were still growing month-on-month. December was an exception, when prices slipped 0.2%. Yet, two developments that took place that month offered a good explanation for what was going.

One was a meeting between President Zelenskiy and gas station operators on December 23 at which the owners agreed to lower gasoline prices. In fact, although for years the price of a liter of gasoline was typically just below a dollar in hryvnia terms, the price of a liter of A-95 gasoline had barely changed since mid-summer, remaining at an average of UAH 28.75 per liter, according to the A-95 Consulting Group. In fact, in the last few years, it had tended to be slightly above a dollar, unlike the past. Prices finally started going down when the dollar fell below UAH 24 in early December, but only by about 50 kopiykas a liter before the meeting with Zelenskiy. Over the month following that meeting, gasoline prices fell another UAH 1.60 per liter. Three days after the meeting, Premier Oleksiy Honcharuk instructed enforcement agencies to shut down all illegal gas stations within two weeks.

RELATED ARTICLE: Old and new risks

The developments around gasoline revealed three important things. Firstly, competition is poor in the Ukrainian economy and market segments are highly monopolized. Thanks to the cheap dollar and steady prices, gas stations were making windfall profits for months. This would be impossible in a developed country. When an industry starts making windfall profits there, the inflow of capital is immediately followed by lower prices for the product. Competition and the fear of losing market share quickly force even the greediest producers to adjust prices for their products. That is missing in Ukraine.

Secondly, nobody, not rivals nor the Anti-Monopoly Committee, seemed to want to solve the problem. It took an intervention from the president himself to get at least some results, illustrating for the umpteenth the power of monopolists in Ukraine and the absence of effective mechanisms against them. It also showed a revival of presidential hand-management of the economy, which is not good, regardless of the results in this particular instance.

Thirdly, the president had to make concessions to the gas station operators to reach his goal. It was most likely these operators who insisted on having illegal operators shut down, in exchange for reducing prices. This also shows the power of the legal operators. Nobody mentions the fact that illegal chains may have popped up precisely because they saw that they could compete with the monopolists by offering more reasonable prices that reflect the market more accurately. Shutting them down will help the monopolists make up whatever they lost, regardless of oil price or dollar rate.

The other development was a decline in rates for natural gas. Officially, started changing in May, but the changes were not felt until November. In December, it finally went down 11.2%, according to Derzhstat. This also did not happen without the intervention of the country’s leadership: on November 30, President Zelenskiy hosted a meeting on this issue while Premier Honcharuk actively talked it up in the press in December.

Checking monopolies and their rates

December statistics and the actions that led to these numbers deserve some consideration. In Ukraine, inflation has two important components whose prices are not determined by the market. The first is monopolist/oligopolist. Economic theory says that the law of supply and demand is undermined in monopolized markets, as monopolists can set whatever prices suit their interests. The situation with gasoline prices was just the tip of the iceberg that Zelenskiy touched.

How many more monopolized markets are there in Ukraine? A study by the NBU showed that, while car prices reflected dollar dynamics very well, as dozens of international makers and dealers compete strongly for Ukrainian buyers, prices for household appliances barely responded to the cheaper dollar although 90% of appliances in Ukraine are imported. This strongly suggests that a cartel is colluding in an attempt to make high profits on a highly concentrated market. In the past, the Anti-Monopoly Committee exposed signs of cartels among chains of supermarkets, gas stations, and others. If the Committee worked effectively, it would find a good dozen industrial sectors with signs of monopoly or oligopoly, neither of which ever lowers prices voluntarily. After all, the president cannot possibly meet with each of these business groups to persuade them to make prices more reasonable.

The second component is consumer rates. The government strongly influences rates for a wide range of goods and services, directly or indirectly. It sets natural gas rates directly and it influences the price of alcohol and tobacco through excise duties that are set in the budget very year. Meanwhile, education and healthcare seem relatively market-driven sectors, but most facilities are owned by the state, so the cost of their services depends on government decisions. Similar examples are plentiful.

All these non-market-driven components of inflation lead to serious problems. Prices for certain categories of goods hardly ever go down, but they leap up whenever there is an opportunity to do so. It’s as though they wrap Ukraine’s inflation rate in a hard shell that prevents it from properly reflecting the dynamic of supply and demand. In developed countries where the mechanisms of their economic systems are far more precise and effective, and competition is incomparably higher, the inflation rate is good at showing the temperature of the economy. Competition prevents unjustified price increases: whenever prices spike, everyone understands that something bad is happening and the economy is close to overheating. When demand is too low, competition forces producers to quickly lower prices in order to sell their goods. So, when inflation approaches zero or deflation kicks in, it’s understood that the economy is entering a crisis. Indeed, this is actually worse than rapid price growth.

Unfortunately, such mechanisms do not work properly in Ukraine. Because the two inert, non-market components are so important, Ukraine’s inflation rate is double-digit when the economy begins to overheat, yet it never manages to go down to zero when there is a crisis of effective demand. This is similar to mechanics: in a system of two balls, where one moves and another does not, the center of the system’s mass has to move at half the speed of the first ball. Overall, Ukraine’s indicators create a false impression of movement where the key component is actually standing still. And that is key.

Taking the economy’s temperature

The consequences are easy to see. Annual inflation was 3.2% in January. Taken out of context, this figure looks good. Stripped of the monopoly and rate components, however, the result is dramatically different. Yet this shows the real situation in the economy. If Zelenskiy had spoken to supermarket bosses or appliance chain owners, the January inflation rate would have been far lower. Another important fact is that the two industries where prices have grown the most are education, up 13.5% year on year, and alcohol and tobacco, up 12.6%. The state directly affects these two categories because they are part of the controlled rate component. If they are taken out of the formula, the outcome changes even more.

In short, price growth would be much lower even than what Derzhstat reported if the current inflation rate were looked at without the inert components. Indeed, it might even be deflationary, which would create serious grounds for concern rather than joy over the economy. Something similar happened in 2012-2013 under the Azarov Government, when the economy suffocated from a lack of effective demand.

It matters not where the causes of the current crisis signals – industrial layoffs, reduced budget spending or insufficient lending – come from. What matter are the consequences. The Government says that the economy is doing well, but there are reasons to doubt that. If officials are saying this strictly for public consumption, then that’s not so bad, provided that they are doing the right things to move out of the risk zone. However, if the leadership actually believes what it is saying, an economic crisis is inevitable and will arrive far sooner than expected. The “40% economic growth in five years” will end up being just another pompous bit of fakery – which the current administration seems to like to produce.

Such a line of thought is supported by a number of key indicators. The dollar has been growing against the hryvnia since December and was 2.2% higher on average in January than in December. But prices grew just 0.2% in January, even though January inflation has hardly ever gone below 1.0% in the past. How much, then, did the market component fall? With the dollar growing stronger in the last few weeks, its annual decline eased from 15.0% in December to 13.5% in January. But annual inflation has continued to decline, from 4.1% in December to 3.2% in January. There is hardly any explanation for this, other than weak demand.

Orienting the National Bank

The paradox is that this imperfect, quasi-market, inert inflation rate forms the basis for the NBU’s inflation targeting policy. The regulator has set a goal to establish a stable inflation rate in the 5±1% range. Formally, this is a sound target that should bring Ukraine closer to most progressive states. But in reality, annual price growth of 5% in Ukraine’s highly uncompetitive economy is the equivalent of 2%, 0% or even -1% in the US. The first option could well be the right one, but given the overall dynamic of macroeconomic processes, the impression is that January’s 3.2% inflation is the same as -1% in a more developed country: deflation caused by the lack of effective demand. In the US, all the economists would be lamenting by now, especially those working at the Federal Reserve. In Ukraine, too many of them keep saying that the economy is doing well, including some who seemed on the ball not that long ago.

This is leading to a very specific problem. The NBU has been building its monetary and currency policies on inflationary forecasts. For example, the higher the forecast inflation, the higher the NBU’s interest rate, with the downward dynamic the same. This should be the right mechanism, as it works in many developed economies. In Ukraine, however, the movement of prices in the inert components is not in line with market trends, so the standard extrapolation methods in the NBU’s forecasts are not actually working as they should.

In October, the National Bank predicted that inflation would be 6.3% at the end of 2019. In fact, it was only 4.1%. The 2.2% difference for such low figures is quite significant and it has left the NBU a month and a half late in its response.On February 6, it published its latest inflation report, anticipating a slowdown of price growth to 3.5% in Q1’2020 and a minimum of 3.2% in Q2. Four days later, Derzhstat reported that inflation was 3.2% in January, below any of the bank’s forecasts. This disinflation seems to not be going away anytime soon, as there are no macroeconomic reasons to support such a shift. Meanwhile, Ukraine is nowhere near the end of the first quarter, let alone in the second one.

Is all this a reflection of incompetence in the executive or flaws in the basis for NBU policy? Whatever it is, quality policies require a reliable analytical foundation. In the short run, Ukraine cannot do much about the non-competitiveness of its economy or the quality of inflation indicators, but it can apply appropriate expert adjustments that take into account the nature of its economy. Forecasts or decisions about the prime rate should be adjusted accordingly. Otherwise, the NBU will continue to come up with imperfect solutions that raise criticism, even if the regulator is doing so with the best intentions.

Flying in the comet’s tail

Even if the questionable quality of the NBU’s forecasts is overlooked, it is hard to ignore its excessive conservatism. On January 31, it set the prime rate at 11.0%, 2.5 p.p. down from the rate set on December 13. In the past few months, however, the average disinflation rate was close to 1.0pp. If the prime rate is lowered 2.5pp every six weeks in this context, the ratio between it and inflation – reflecting the real rate – will change too slowly.

RELATED ARTICLE: When the economy starts to ferment…

Economic theory says that the real interest rate is what affects effective demand and, therefore, economic growth. In Ukraine, the real interest rate, based on statistical expectations, meaning on real data about inflation, spiked to 8% in July 2019 and has barely gone down since. The NBU claims that the optimal interest rate should be 2-3pp above inflation, that is, 7-8% with 5% inflation, but in fact, it has been keeping it far higher. This policy probably made sense in early 2018, when Ukraine was facing huge uncertainty in cooperation with the IMF and badly needed foreign funding. It could have been justified even a year ago, when Ukraine was going into two elections, which tended to push non-residents to move capital out of the country.

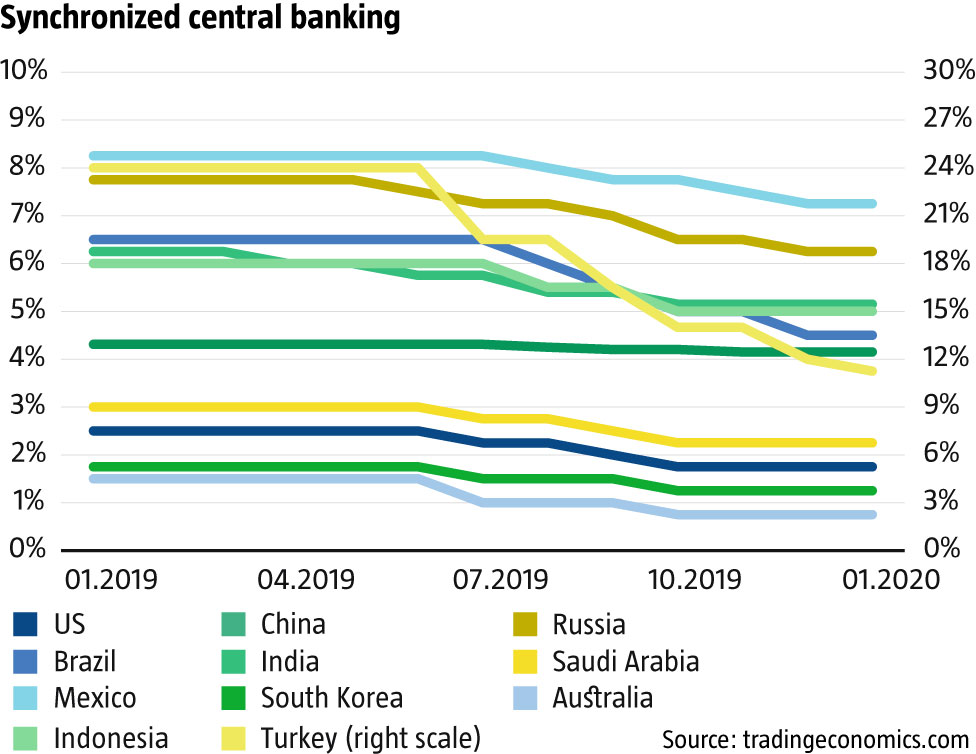

But the NBU’s overly conservative policy surfaced when the Federal Reserve started lowering interest rates in July 2019, followed by the central banks of 11 of the 20 largest economies (see Synchronized central banking). While dozens of countries were loosening their monetary policies, the NBU seemed in no hurry to do the same. Foreigners took notice and grabbed their chance: Ukraine saw an unprecedented inflow of foreign money for its government bonds. The side effects included a steep revaluation of the hryvnia and an abnormal slowdown in inflation, which has already gone below the floor of the NBU’s forecast range.

As a result, Ukraine found itself in a disinflationary nosedive. Excessive real interest rates stifle economic activity, trigger rapid disinflation and stimulate short-term financial speculative behavior. This did not raise serious threats for the economy for a while. But if the current disinflation and interest rates continue to decline, the real rate will hit a normal 3% at the end of the year, when inflation is deeply negative. This will put Ukraine into a full-blown economic crisis.

To be fair, the NBU started working more proactively on the currency market in late December. It has been buying back more foreign currency, thus injecting more hryvnia into the system and allowing the currency to support a rising dollar exchange rate. In time, this policy should support inflation and balance out the bank’s earlier overly conservative monetary policy. Still, this looks too much like giving with one hand while taking with the other.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook