On October 19, speaker Andriy Parubiy urged MPs to hurry with their speeches. Half an hour remained until the end of the allocated time and three bills on changing the system for elections to the Verkhovna Rada still needed to be voted on.

In the end, the deputies made it on time. "Dear colleagues! I would like to inform you that we have completed the first stage of the electoral reform!" announced the speaker. The chamber replied with loud laughter and some MPs started clapping. Although they finished on time, MPs rejected all three proposed projects. Which was why Parubiy's turn of phrase was considered an apt joke.

"Attention! We still have two more electoral codes to examine. In the next plenary week, we will continue to look at two codes for electoral reform, one of them authored by your respected and beloved Andriy Parubiy," continued the speaker. The chairman of the Rada flashed a smile and paused so that MPs could appreciate his new joke, then added, "And one by Pysarenko".

The tent town that remained after the Great Political Reform protest launched on October 17 had been standing outside Parliament for two days. Although the initiators of the event have different views on its future and most of them have declined all responsibility for what happens in the camp, the Rada dedicated the day to looking at two of the three demands declared by the protestors.

Among them was the "change of electoral rules". In the statements and comments of protest leaders, this topic was mostly overshadowed by the other two – the abolition of parliamentary immunity and the establishment of the Anticorruption Court. However, on the official website of the campaign, the electoral reform was on top of the list.

RELATED ARTICLE: Populism's last gasp: What political ambitions do Yulia Tymoshenko and her party hope to achieve before the 2019 elections?

"Ukraine has a mixed proportional and majoritarian electoral system, adopted in 2011 in the interests of the Yanukovych regime. This means that half of MPs are elected in majority constituencies, where they win mostly by bribing voters and using administrative leverage, and the other half from closed, proportional lists, in which places are often sold. This system is the root of political corruption in the country," read a statement on the Great Political Reform website. It was demanded that MPs approve bill No. 1068-2, authored by several deputies headed by Viktor Chumak, one of the leaders of the protest in front of the Rada.

In fact, the Chumak-sponsored bill was one of the three that the Rada rejected during the evening session on October 19. It garnered the most support out of all those submitted, but still not enough – 169 votes. However, this does not mean that the matter has been put to rest. In fact, the draft electoral code No. 3112-1 announced by the "respected and beloved" Andriy Parubiy was virtually identical to Chumak's bill in the section concerning parliamentary elections. In fact, both documents are only formally new. They duplicate the provisions set out in Yuriy Kliuchkovskyi's draft electoral code that had been registered back in 2010. Therefore, the fate of the demand for open-list elections would be decided after 6 November, when MPs returned from yet another recess.

Different models

Currently, Ukraine has a mixed system for general elections. This means that half of Parliament – 225 deputies – are elected under a proportional system with parties running with closed lists of candidates. Prior to elections, parties adopt a single national list at their conferences and candidates positioned highest on the list win seats depending on the percentage of votes cast in their constituencies for their political force. The holders of the remaining 225 seats are determined in single-member constituencies, where not only representatives of parties, but also independent candidates can stand.

On October 19, MPs could choose one of the three suggested ideas to replace this formula. The bill registered by former Party of Regions member and current representative of the Opposition Bloc Yuriy Miroshnychenko basically duplicates the electoral system that functioned in Ukraine from 2004 to 2011: parties and blocs form closed lists and then have to receive a percentage of votes that exceeds a certain threshold. However, the author was unable to conclusively decide what this limit should be: different articles of the bill refer to 1% and 3%.

Batkivshchyna party leader Yulia Tymoshenko and her allies proposed a more interesting scheme. The country would be divided into 450 constituencies (as well as an overseas constituency), in which parties nominate one candidate each. Voters choose a party and a candidate at the same time. It looks simple: one constituency, one deputy. It is more complicated in practice. The top ten candidates on each list automatically receive seats in Parliament if their party gets at least 5% of total votes around the country. The rest of the seats are distributed according to results in the constituencies.

The third idea, which still has chances of success, is included in the Chumak bill and is also set out in the code authored by Parubiy, as well as two other MPs, PPB’s Oleksandr Chernenko and People’s Front’s Leonid Yemets. In a nutshell, it proposes dividing the territory of Ukraine into 27 constituencies, which in most cases coincide with the current oblasts. There are three exceptions. One is Kyiv, which is split up into two regions (Left Bank and Right Bank, with the Pechersk and Holosiyiv districts of the city included in the Left Bank). Dnipro Oblast is divided into the Dnipro and Kryvyi Rih electoral regions, while the Southern Electoral Region would include Kherson Oblast, the Crimean autonomy and Sevastopol. Parties will put forward separate lists of candidates in each electoral region.

If this law is passed, voters will no longer be able to simply tick a box next to their chosen party. According to the authors' plans, the ballot paper will have two columns: "I support the electoral list of the political party under … number" and "I support the candidate for People's Deputy of Ukraine from this political party under … number". Next to each column, there will be a box for the numbers. If the voter supports the party number 9, for example, and regional party candidate number 3, then "09" should be written in the first box and "03" in the second.

After the voting, the Central Election Commission establishes the percentage of the votes each party received in Ukraine as a whole. This is the only disparity between the bills by Chumak and Parubiy. The first one proposes a threshold of 3%, the second one – 4%. Seats in Parliament will be divided among the parties that go over the threshold. Now, the seats go to the candidates as in the list approved at the party conference. Under the new bills, the selection of winning candidates should be based on the popularity of specific candidates in a particular region. For example, party A receives 5% of the total vote around Ukraine and party B gets 10% — these are the only political forces to have passed the threshold. Accordingly, party A will claim about 150 seats and party B will get 300. The second column on the ballot paper will determine who exactly will become the MPs for these parties. Let's suppose that A received all its votes in only two regions: 75% in one and 25% in the other. Accordingly, 113 most popular candidates from the party list in the first region and the top 37 from the second will become MPs. No candidates will be elected to Parliament in the regions where the party is unpopular, although the draft law requires the nomination of candidates in all 27 constituencies.

Counting the MPs

The current system for parliamentary elections in Ukraine virtually guarantees the victory of pro-government forces. The key reason behind this is single-member constituencies. Thanks to them, the pro-government party increases its representation by about 50%. For example, at the 2012 and 2014 elections, the parties then in power (the Party of Regions and Petro Poroshenko Bloc) won 51% and 35% respectively of all seats in single-member constituencies. These results were far from the national ratings of the parties, which was reflected by the results under the proportional electoral system – 30% and 22%, respectively.

In addition, the party in power always has one more hidden tool – independent candidates. At the 2012 and 2014 elections, these candidates received 19.5% and 48% of single-member seats respectively, getting 43 and 96 seats in Parliament. For comparison, the parliamentary faction of the most popular party at the last election, the People's Front, now only has 81 members. After winning their seats, independent candidates can either join a faction (which often turns out to be the ruling faction) or create their own associations and groups, which can be used to push through various unpopular decisions. On the other hand, other political forces in Parliament, apart from the "faction of power", cannot boast such impressive results in single-member constituencies. Not to mention the small parties, which are not represented by parliamentary factions at all. At the 2012 and 2014 elections, these political forces only won 29.5% and 17% of all seats respectively (63 and 33 MPs).

The reasons behind this situation lie in the single-member constituencies, which have long been associated with administrative pressure and various forms of voter bribery. According to Oleksiy Koshel, head of the Committee of Voters of Ukraine, majoritarian MPs are the main opponents to any changes in the electoral system: "We can already see dozens of constituencies that get massive subsidies and investments, which turns majoritarian MPs into feudal politicians that are guaranteed to win or have the right person elected. The current system is convenient for many local politicians."

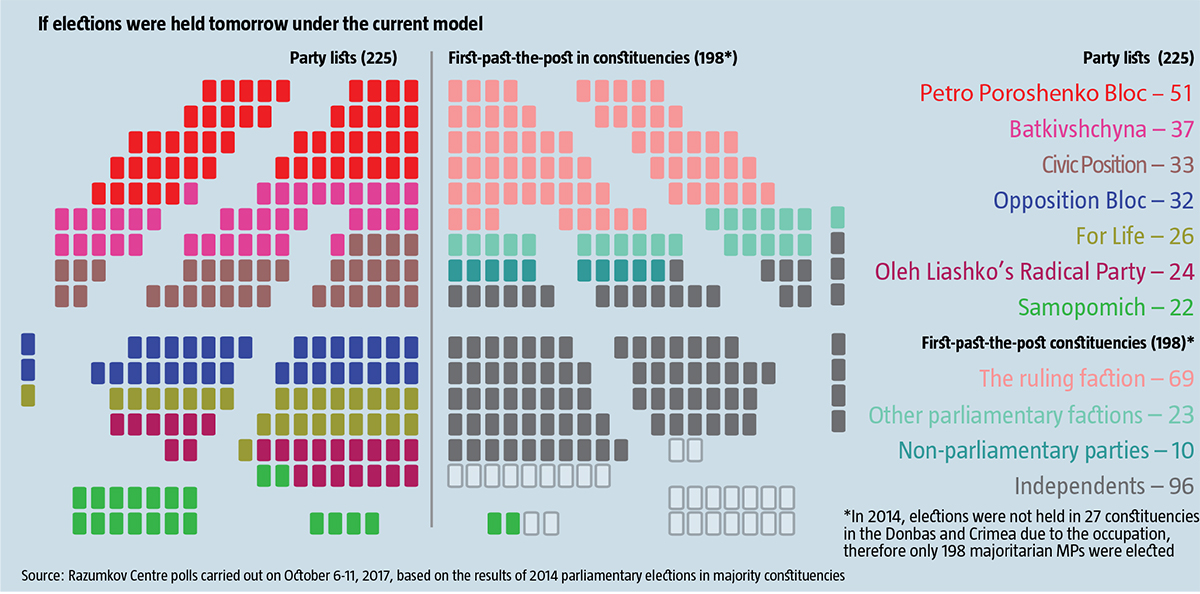

If we try to simulate future elections under the existing system, based on the latest poll data and the results from single-member constituencies in 2014 (see If elections were held tomorrow under the current model), then it is obvious that they will only be beneficial to the Petro Poroshenko Bloc and independent candidates, the latter receiving more votes as the president’s brand is losing popularity. In fact, if this system is preserved, independents in the next convocation of the Rada will not be "worth their weight in gold", but in platinum, which will be reflected in the price of their votes. Likewise, the level of populism will grow, because almost every independent MP will try to assume the role of a passionate "protector of the ordinary people". In such circumstances, any unpopular but important decisions can be forgotten about.

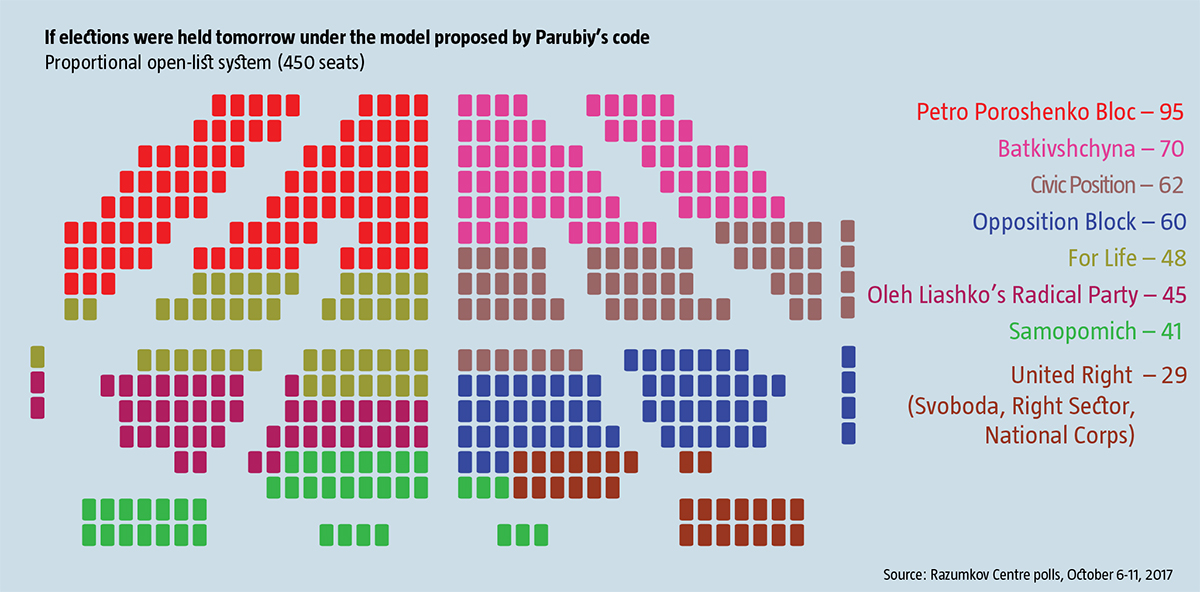

Voting in parliament for Viktor Chumak's bill to change the election system generally reflects the interests of the parties (see What about open lists?). For example, most members of the Petro Poroshenko Bloc faction and the People's Front did not vote in favour. Almost half of non-affiliated MPs ignored the vote, while members of Vidrodzhennia and Volia Narodu groups, comprised mostly of MPs elected through single-member constituencies, cast one vote between them. However, there are other things that are difficult to explain logically. For example, the voting of the Opposition Bloc faction. Simulations show that if a system with open lists is introduced, this party could almost double its number of MPs, but only one member voted for the draft law. Similarly, the Radical Party and Batkivshchyna factions did not give their 100% support either, although a change in the system should be advantageous for them (see If elections were held tomorrow under the current model and If elections were held tomorrow under the model proposed by Parubiy’s code).

Alternatively, the Petro Poroshenko Bloc party would probably not be particularly affected by the introduction of regional constituencies and open lists. Since results at the local level will be the most important, the party could recruit popular local politicians who were previously nominated as single-member candidates and gain votes thanks to them.

According to Oleksiy Koshel, most MPs did simply not understand what they were voting for. "The bill demanded by the protesters (Chumak's – Ed.) is actually convenient for current political forces and extremely convenient for corruption. Moreover, it is a very comfortable law for majoritarian MPs. After all, it's convenient for those who have support, give their voters incentives, create mini funds, build roads and take advantage of political subsidies, because under such a system the parties would have to compete for these popular majoritarians to bring them into their lists. What's more, I can't even rule out that a new political force with a neutral brand would be formed just to unite dozens of successful single-member MPs. The proposed system is a step forward, but it would only partially solve the issue of corruption," he says.

According to Koshel, at this stage it is necessary to unequivocally abandon the majoritarian system in favour of a proportional one, even with closed lists. This would reduce the probability of voter bribery, but has another problem – the sale of positions in party lists. Therefore, it would be necessary to create safeguards against this. In addition, he emphasises the need to ban political advertising, which is not required by any of the bills proposed to MPs: "This is a measure that would make elections more meaningful, because the parties would have to offer something more than 10-second videos with a catchy slogan and emotional imagery. It will also reduce the cost of elections in Ukraine three, four or five times over. On average, Ukrainian parties spend three or four times more than their Polish counterparts do during elections to the Sejm. Reducing the cost of elections is a way to give new parties a chance at success. In the current circumstances, new parties will never be able to compete with the parliamentary groups because they do not have enough money. A ban on advertising is no less important than changing the system itself."

RELATED ARTICLE: Are Ukrainians ready to protest? Protest mood and confidence in state institutions in Ukraine according to sociologists

Olha Aivazovska, chair of the board at the Opora Civic Network, is also convinced that MPs did not particularly look into what they were voting for and pointed out that any proportional system primarily frustrates the authorities because it makes it far more difficult for them to use independent candidates as a tool. In addition, the proposed open-list system makes it difficult to predict election results: "There is one nuance in the unknown number of seats assigned to each constituency. Not to a particular party, but in general. It is linked to turnout, which is always the highest in Western Ukraine. We took the parties and did another simulation based on the 2014 election results, but this time taking into account the turnout. For example, Lviv Oblast could get 34 seats – almost three times more than now. No political players would know how many seats each constituency would get – there are 27 constituencies. Looking at past turnout figures, they realise that this is dangerous, as there will be more MPs in the West due to the fact that the number of voters going to cast the ballot there is traditionally higher."

Olha Aivazovska, chair of the board at the Opora Civic Network, is also convinced that MPs did not particularly look into what they were voting for and pointed out that any proportional system primarily frustrates the authorities because it makes it far more difficult for them to use independent candidates as a tool. In addition, the proposed open-list system makes it difficult to predict election results: "There is one nuance in the unknown number of seats assigned to each constituency. Not to a particular party, but in general. It is linked to turnout, which is always the highest in Western Ukraine. We took the parties and did another simulation based on the 2014 election results, but this time taking into account the turnout. For example, Lviv Oblast could get 34 seats – almost three times more than now. No political players would know how many seats each constituency would get – there are 27 constituencies. Looking at past turnout figures, they realise that this is dangerous, as there will be more MPs in the West due to the fact that the number of voters going to cast the ballot there is traditionally higher."

She goes on to say that the proposed system does not guarantee that nobody will abuse it, but it does significantly reduce such opportunities and increases their cost. In her opinion, candidates are more likely to try to falsify the results of the vote than directly bribe voters: "This system makes it very complicated to simply divide up territory as before, prevent the nomination of strong competitors from other parties and make arrangements beforehand, as it is now often the case during elections in single-member constituencies. If we talk about bribery, it’s not the electoral system that’s supposed to fight against it, but the inevitability of punishment."

Oleksiy Koshel from the Committee of Voters agrees. In his opinion, as long as there are few precedents of prosecution for electoral crimes, there will be no incentive for a political culture to grow. He points out that as of today less than 10% of bribery cases opened after local elections in 2015 have gone to court. "For me, the case of the students in Chernivtsi who were involved in bribing voters at the last local elections is very revealing. The man behind the fraud was abroad and is free as a bird, while several students will get suspended sentences and possibly even have their lives ruined. This is a classic example of the ringleaders avoiding punishment. The reason behind this is the ineffectiveness of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in investigating electoral crimes. They should initiate legislative changes, as it is not only the fault of law enforcement, but also significant gaps in the law. The Ministry of Internal Affairs should conduct training for the investigators who deal with such crimes," he says.

Nevertheless, he believes that the political culture of voters is improving slowly but surely and that bribery techniques are no longer as effective as 10 or 15 years ago. "Recovery from this will probably last for decades, but even our western neighbours – Poland, Slovakia and Romania – also have problems with voter bribery, just on a smaller scale," the head of the Committee of Voters concludes.

It is difficult to predict whether MPs will approve any changes at all. Given the result of voting on the Chumak bill, we could assume that "Parubiy's" electoral code was 60 votes short of getting through its first reading. This number did not seem unrealistic, however, according to The Ukrainian Week's sources, the prognosis was pessimistic: either the electoral codes would be voted down in full or at best sent for another first reading, which at least left a chance that they would be examined again.

On November 8, MPs surprised many by passing the bill co-sponsored by Parubiy, Chernenko and Yemets in the first reading with 226 votes, including from the Opposition Bloc. What happens next is anyone’s guess. For now, sources in the Rada are pessimistic about chances to pass the new election code.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook