As if there was ever any doubt, “I plan to run for the presidency,” Yulia Tymoshenko announced on the eve of Pokrova, October 14. “And we will win in order to put the country back on its feet. I don’t trust anyone else to do the job.”

The Batkivshchyna leader flung the comeback glove at all her one-time political allies, now her main rivals in the upcoming elections. To her disciples, it was a signal: only she could make all the prophecies of psychics, clairvoyants and other fortune-tellers that only a woman president can save Ukraine come true.

Do we have a plan?

What may have spurred Tymoshenko to such an announcement is hard to understand. It did not come across as a spur-of-the-moment statement, although one could possible see it as a Freudian slip. Until not long ago, it seemed that the Gas Princess understood her paltry chances and had pretty well stopped dreaming about the post of president.

Of course, this did not at all mean that her political ambitions had shrunk, let alone disappeared. On the contrary. Having understood where the real power lay hidden, the Batkivshchyna leader apparently began to seriously bring up the idea of being premier for the third time, although not in its present shape. It seems that she had a very clear plan for amending the Constitution to grant the Head of Government nearly unlimited power while weakening considerably the role of the president. The latter was to become a kind of figurehead while the real power would shift to the PM, who would be determined by the majority in the Verkhovna Rada.

In order to become PM, Tymoshenko would first have to control the legislature or be able to cut a deal with someone. And this looks like where her premierly ambitions probably ran aground. Cutting deals with Tymoshenko has always been fraught, as those who have been incautious enough to get involved in alliances with her can attest—“because Yulia likes to dump people.” But maybe that’s more of a slur than a fact, most likely started by those who themselves dumped Tymoshenko at one time or another and are now regretting it. In any case, it looks like this grand plan to amend the Constitution the way she wants is already being seriously developed on by an entire working group.

But Batkivshchyna will not necessarily propose this on its own: they could easily organize a cluster play, with others who stand to gain from such changes making the first move. The idea itself has been hanging around for many years now. Efforts were made to bring  it to life during the Yushchenko Administration, when PM Tymoshenko held negotiations to form a coalition with the then-president’s nemesis, Viktor Yanukovych. Talk was about amending the Constitution to shift the balance of power between the president and premier. As Yushchenko himself eventually explained, the president was going to be elected by the Verkhovna Rada and his powers greatly reduced—Yanukovych, incidentally, had no objections to that then—, while the premier was going to have greatly expanded powers and no term limits.

it to life during the Yushchenko Administration, when PM Tymoshenko held negotiations to form a coalition with the then-president’s nemesis, Viktor Yanukovych. Talk was about amending the Constitution to shift the balance of power between the president and premier. As Yushchenko himself eventually explained, the president was going to be elected by the Verkhovna Rada and his powers greatly reduced—Yanukovych, incidentally, had no objections to that then—, while the premier was going to have greatly expanded powers and no term limits.

RELATED ARTICLE: Are Ukrainians ready to protest? Sociological surveys on protest mood and confidence in institutions

Needless to say, Tymoshenko was planning to be that lucky premier, but things didn’t quite work out as plant. Yushchenko outplayed her and persuaded Yanukovych not to trust her because he would pay dearly. Yanukovych thought about it and decided to back out of the budding alliance and the expansionist initiative fell apart, but never died. Today, Tymoshenko is hardly the only politician who still would like to see such a shift. Narodniy Front (People’s Front) people say that Arseniy Yatseniuk and his pal, Interior Minister Arsen Avakov are interested in trying to shift the balance in this way so that the president won’t be able to concentrate the most power. Hence the “weak presidency, strong premiership” model that Yatseniuk has already brought up. Only Poroshenko is not exactly thrilled by the idea.

Have Batkivshchyna and Narodniy Front tried joining forces to see their common dream come true? Some meetings did take place, but even though such an alliance seems to make sense, it is very unlikely. It all comes down, once again, to trust. Both Yatseniuk and Avakov have lived in the Batkivshchyna compound and know what Tymoshenko’s promises are worth, even if an agreement were to be signed in blood. In the end, it will be easier for her to cut a deal with more minor, ideologically empty parties—certainly it will be cheaper, at any rate—that pass the threshold in the next election. These could be Oleh Liashko’s Radical Party and Vadym Rabinovych’s Za Zhyttia. But until the Rada elections roll around, why not play around with the idea of running for president? It offers additional opportunities not only to gain publicity, but also to raise her party’s profile and expand her business options. After all, why should political power be the only aim of such a powerful party?

Naked business

A few months ago a member of Batkivshchyna’s political council over 2005-2007, businessman Mykhailo Brodskiy, admitted in an interview that during his time, a “guaranteed spot on the party’s election list cost between US $3 and 5 million” and that this practice “had not changed much.” “Unfortunately, the system is designed in such a way that it’s really Big Business,” Brodskiy added. What Brodskiy revealed was hardly news to anyone. Similar stories have circulated about Batkivshchyna since the day it was launched… and at all levels, from county councils to the national legislature.

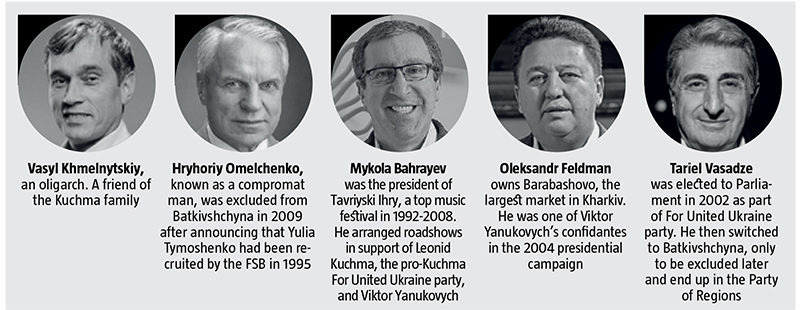

Indeed, the history of Batkivshchyna has been the story of a “transit zone” for many dubious but moneyed politicians. Just a few surnames make that amply clear: Bohdan Hubskiy, a member of SDPU(o), close ally of the odious Viktor Medvedchuk and a representative of the so-called Kyiv Clan; Yevhen Sigal, also from the SDPU(o) and a long-time member of its political council; Kuchma family friend Vasyl Khmelnytskiy; well-known banking brothers Serhiy and Oleksandr Buriak; car magnate Tariel Vasadze; and oligarchs Kostiantyn Zhevago and Oleksandr Feldman.

It’s understood that, without their direct testimony, it is be impossible to confirm certain financial relations with the party, but judging by the scale and consequences of its activities, it is equally hard to deny that this stream turned into a serious business. And the growing popularity of the party only increased the cashflow, but whenever problems arose, all the transit passengers hopped off the train. And so it was no surprise when the VI Convocation of the Verkhovna Rada saw BYT become the source of 38 tushky or party-hoppers, while in the VII Convocation, Batkivshchyna “donated” 13 more tushky to its rivals. Brodskiy described this phenomenon in a few words: “The system was such that people bought a spot on the party list, then turned around and betrayed it. They considered that they had simply paid for the right to a seat in the Rada.”

Some might expect that Batkivshchyna has changed since those long-ago days, but not at all. Of course, it’s been dropped by many big names, such as Oleksandr Turchynov, who seems to have gotten tired of playing “Yulia’s shadow” and decided to try out some headline roles on his own. Indeed, the party has grown far younger and can boast graduates from Harvard and Oxford today. But the leader has not changed, which means the basic human resource principles have also not changed. “Our girl will do everything for us,” one of the regional functionaries of Batkivshchyna responded when asked why he was so inactive.”

A motley package

With no ideological foundation whatsoever and a penchant for primitive demagoguery, Yulia Tymoshenko performed miracles to attract the hearts of uninformed voters to support her. Oozing both affective and effective populism, she attached to herself legions of fans and half-crazed grannies who did not even try to understand where she was coming from. “Our Yulia” was enough for them. It’s hard to say that she grabbed them with her intellect or her deep wisdom. She was simply personally very appealing.

And this blinded electorate was ready to take anything at face value, from fairytales about how candidates from BYT signed documents stating they rejected state apartments and immunity, to nonsense about Batkivshchyna arming itself with the ideology of solidarity. Say what you want about Yulia, but she was able to guarantee her own popularity at a very decent level—something that is still true today—, and this kept attracting “buyers,” those who wanted to gain a seat, whether in a local, county or oblast council or the Rada itself. Indeed, Tymoshenko has established a kind of multi-level marketing system that draws people with political ambitions, generally in business or offering some other interesting “resource” to her party.

The Batkivshchyna leader is good at manipulating in the international arena as well. Reputed foreign publications carried two landmark articles penned by her—or by her loyal Batkivshchyna shadow foreign minister, Hryhoriy Nemyria: a hawkish one in 2007 about the need to contain Russia, and a second one in 2009 about Ukraine’s and Russia’s common “European calling.” Nor is this the only example of cognitive dissonance: in its search for allies, Batkivshchyna has freely swung from the rightist European People’s Party to the Socialist International.

RELATED ARTICLE: The reaction of Ukrainian social media users to President Poroshenko three years into his term

What about Tymoshenko herself: did she ever believe in anything that she said or promulgate? Certainly she always had a very strong team working with her to develop the necessary messages and slogans that one could easily believe in without really getting into their essence—and no trace of an ideology. Of course, those who needed to see one there, in that ecumenical Babylonian cauldron, then that, too, was included in the package of services.

But when there was no team and Tymoshenko had to improvise, the bloopers were quite remarkable: giggling next to Putin just as he was invading Georgia. Whatever one may think of Saakashvili, but not to support Georgia in 2008 meant to side with an aggressor  who was in violation of all international rules. Nor was this incident some kind of clever political quid pro quo. She didn’t do this because she was some kind of FSB agent, beholden to Putin or out on a limb. No, that incident showed the real Yulia Tymoshenko, the inevitable paradox when an image pasted together by professional admen is diametrically opposed to the real person behind it—and how just easily that image can cloud over the minds of hundreds of thousands of people. How they can be made to believe in something that never existed because it could not have existed, and thus to love, not the person, but the packaging—and only the motley package. The real Yulia is known only to those who are closest to her, those whom she allows to see her.

who was in violation of all international rules. Nor was this incident some kind of clever political quid pro quo. She didn’t do this because she was some kind of FSB agent, beholden to Putin or out on a limb. No, that incident showed the real Yulia Tymoshenko, the inevitable paradox when an image pasted together by professional admen is diametrically opposed to the real person behind it—and how just easily that image can cloud over the minds of hundreds of thousands of people. How they can be made to believe in something that never existed because it could not have existed, and thus to love, not the person, but the packaging—and only the motley package. The real Yulia is known only to those who are closest to her, those whom she allows to see her.

Just one good example is her participation in a session of the National Security Council at the very beginning of the war in Ukraine, when she talked about the need to demonstrate peacefulness. Perhaps she was advised to do so, but it was a piece of advice that most suited Tymoshenko’s character—an iron lady who turned out not to be no warrior after all, not determined, not principled, and absolutely not “with Ukraine in her heart…” Afterwards, of course, every situation is open to interpretation or even denial. And for Tymoshenko, this has always worked beautifully. Ukraine’s own post-fact politician.

A dangerous moment

It’s hard to say who is Tymoshenko’s closest confidant today. After Turchynov left, his place seemed to be taken up by Oleksandr Abdullin, a long-time ally and business partner of Leonid Kuchma’s son-in-law, Ihor Bakai, who fled to Russia years ago, during the Orange Revolution. Prior to joining Batkivshchyna, Abdullin tried being in SDPU(o). Significantly, when Abdullin and his buddies joined BYT, the legendary parliamentarian Stepan Khmara immediately quit both the faction in the Rada and the Batkivshchyna party, where he was deputy leader, in protest. He announced that for him it was impossible to remain in the same company as an odious Kuchma man and oligarch, out of both political and moral considerations. But there was never a shortage of people like Abdullin around Tymoshenko. Of course, there were also many others, with completely positive, pro-Ukrainian credentials, but they had little influence over the business model.

Today, Batkivshchyna is entering possibly the most complicated and most interesting phase of its existence. Time inexorably ticks on and the opportunities to see dreams come true keep shrinking. If Yulia Tymoshenko fails, once more, to carry out her plans in the next while, if she flops in the 2019 cycle of elections, becoming neither president nor premier, she can say good-bye to her political dreams, once and for all. She will join the ranks of political has-beens. To prevent this, Tymoshenko appears prepared to go for broke, betting everything she has on this last throw of the dice.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook