At the end of March 2014, Vadym Rabinovych, president of the All-Ukrainian Jewish Congress came to the Central Electoral Commission to submit his application as a candidate for president of Ukraine. One of his goals, he said at the time, was to tear down the myth of Ukraine as an anti-semitic country.

“I’m probably the most appropriate candidates,” he said at the time. “Today, we need to join forces and I’m a unifying candidate. I don’t have a mania for power. I simply want to help the country.”

On Election Day, May 25, 2014, Rabinovych came in 7th with only 2.25% of the vote. Today, he’s still president of the Jewish Congress but now he is also head of the newly-formed Za Zhyttia or For Life party, and his ratings as a presidential candidate are 3-5%, depending on the poll, with some prospects for growing. The difference in the numbers may not seem like much, but this kind of rating given the current circumstances – a huge field of candidates, for one – means that there is some chance of making it into the second round. Still, on November 15, Rabinovych disappointed his supporters with announcement that he was leaving the race. Moreover, his reason flew in the face of his 2014 statement: he said that he did not think a Jew could be elected president of Ukraine.

“I thought long and hard about it this last night and it seems to me that, as someone who is a practicing Jew, I can not and have no moral right to be a judge over issues involving Orthodox Christianity, which is indubitably one of the duties of the future president,” he explained. “So, unfortunately, I have to announce that I am withdrawing my candidacy. I will not be running for president and will talk to our party council today to immediately nominate another person.”

Consistency seems not to be a strong point among Ukrainian politicians. At the same time, most Ukrainian voters are quite accustomed to it. A Razumkov Center poll showed that only 18% of Ukrainians can “easily” or “very easily” state their own position on political issues. Quite a large proportion of Ukrainians, according to this poll, are quite uninterested in politics and don’t think it’s worth spending time on it. Among the main trends in party building, regionalism and the politics of personality dominate. If all the parties that have registered since the Maidan are considered, their names are pretty self-evident. On one hand, there are Cherkasites, Khersonites, the Gypsy Party of Ukraine, the Georgian Party of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Halych Party, and so on. On the other, there are “Lyashko’s” Radical Party or “Poroshenko’s” Solidarnist, and this is just a very short list.

Interestingly, polls show that, while most Ukrainians favor government regulation in various spheres, around 10%, according to DIF, are against ant government funding for political forces, and another 13% don’t want to pay out of their own pockets. Instead, 49% think party leaders should finance their parties and 48% think the rank-and-file members should. Yet only about 1% of Ukrainian voters are actually members of a party as of 2018.

Given all this, it’s hard to have a serious discussion about the differences among the various platforms candidates are proposing. Only a minority of voters actually reads them. And so election campaigns turn into little more than a competition of advertising campaigns, where form matters more than content. This also makes life easier for the candidates themselves as they don’t need to be too careful about being consistent in their image, their focus or even their positions.

RELATED ARTICLE: The traps of populism

Visual evidence of this can be seen in every election campaign and the presidential election – the race that most Ukrainians consider the most important one – is no exception. Populism is being written and spoken about much these days, but in fact it has been part and parcel of every single election. The 2014 election, despite its exceptional status, was no exception. Its main uniqueness was that it lasted only three months, as is provided for in law. But most of the time, unofficial campaigning typically starts nearly a year prior to Election Day. Yet, the only place where the more-or-less substantive positions of candidates can be heard and registered is during campaign debates. The main focus is generally on the competition in the run-up to the second round of voting, where the two main candidates meet face-to-face for a verbal fight. This did not take place in 2014, as the election was decided in a single round. And so debates took place in a chopped-up format: the top candidates stood, not next to each other but next to anonymous crowds of people and responded to a wide range of questions.

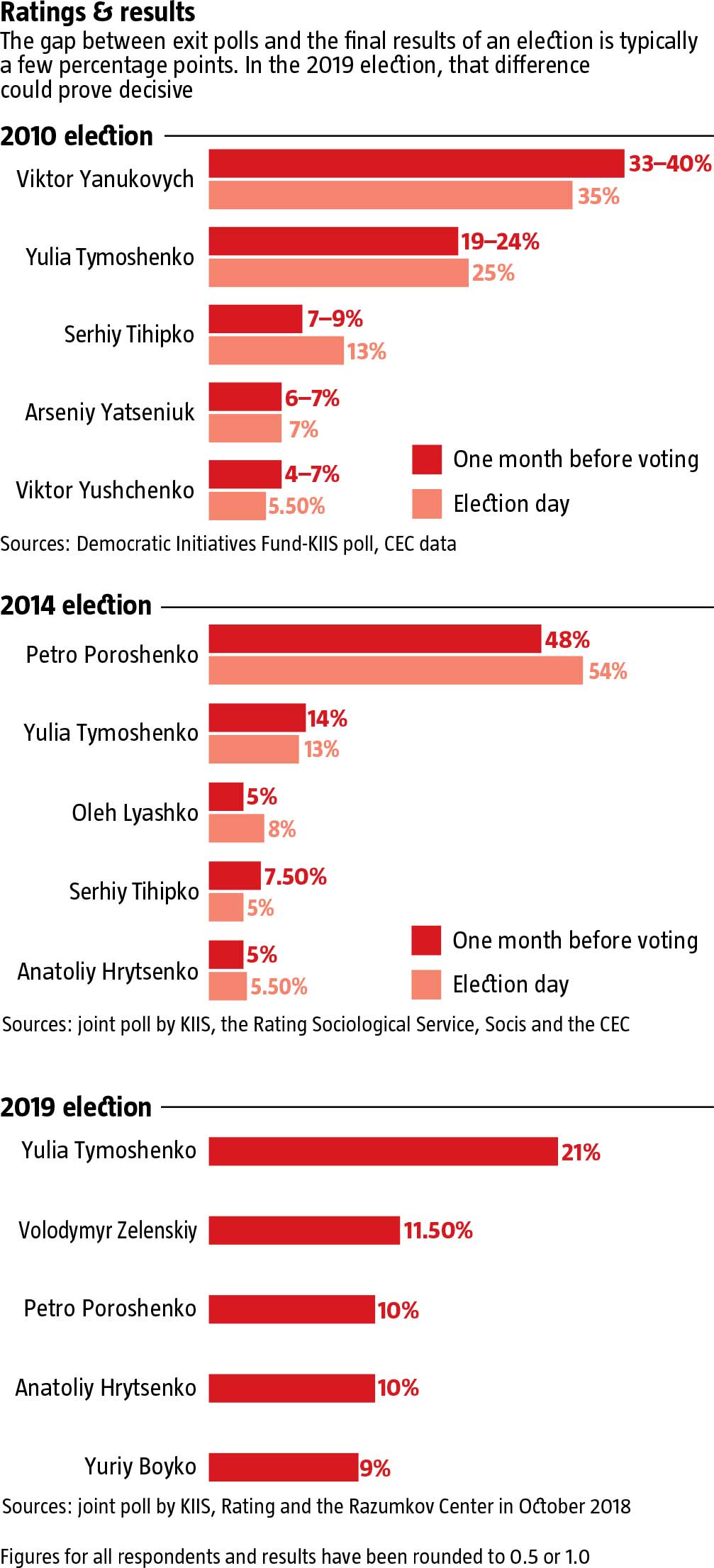

The brevity of the 2014 campaign did not change the fact that the ballot included some 20 names. A similar number has run in all other elections. Registration for the 2019 race has not yet started but it’s pretty predictable that there won’t be any fewer this time. Of the main active candidates in 2014, four of the same politicians are running this time as well: Petro Poroshenko, Yulia Tymoshenko, Oleh Lyashko, and Anatoliy Hrytsenko. Most likely Yuriy Boyko will join them, even though he was 14thin 2014. Mikhail Dobkin has also declared his intentions, after coming in 7thin 2014, when he was considered the main pro-Russian candidate. This was significant as Dobkin’s political ads suffered possibly the most from green and other spray paints. Now the Kharkiv politician is head of the Christian Socialist Party, but he hasn’t been actively campaigning so far.

One of the many questions still open regarding the 2019 elections is who will be the main pro-Russian candidate. Until recently, there were two: Boyko and Rabinovych. However, they joined forces and now Viktor Medvedchuk is involved as well. This is most likely why Rabinovych dropped out. Still, Boyko is hardly short of competitors, including Rabinovych’s one-time ally Yegeni Murayev in his new “Nashi” (Ours) project, and ex-fellow OppoBloc member Oleksandr Vilkul, who has been actively advertising himself on billboards mostly in eastern and southern Ukraine.

In fact, the herd of candidates on the pro-Russian flange is one of the key elements that distinguish this race from the 2014 campaign. Another little detail stands out in this field: in 2014, Dobkin ran as an independent, but demonstratively used symbols of the Party of the Regions in his advertisements together with the slogan “Yedyna Kraina,” echoing “Yedinaya Rossiya,” Putin’s rubber-stamping party in the Russian Duma. At the time, this could have been interpreted as an open challenge and even mockery of those Ukrainians who had supported the Euromaidan and for whom the killings in Kyiv and annexation of Crimea were still painfully fresh memories. The result was a pathetic 3% of the vote.

Even Serhiy Tihipko, who was also associated with the Yanukovych regime but chose the more subdued national colors and the simple slogan, “Let’s restore order and revive the economy,” managed to get a bit over 5%. Half a year later during the Rada elections, Tihipko was to run under the slogan, “Peace, the economy, and the future.” Although it’s unlikely to lead to success, today it’s obvious that his basic strategy beat Dobkin’s. Pro-Russian politicians, with the exception of Medvedchuk, try to avoid directly demonstrating their sabotage of the changes going on in Ukraine today and don’t promise a complete return to the past. Instead, nostalgia for the past is demonstrated in flowery greetings on every possible holiday, but mainly it comes in promises of peace – without any indication of the possible conditions involved. True, in the 2014 debates, Tihipko did manage to find the strength to acknowledge the annexation of Crimea by Russia, something that can’t be said about most of the candidates in the pro-Russian camp today.

Anatoliy Hrytsenko is from the other camp, but has also shifted the emphasis in his 2019 campaign, compared to 2014. Then, the one-time defense minister appeared on billboards in camouflage under the slogan “I guarantee security.” Now he’s in a business suit and the slogan reads, “Honest folks are in the majority.” In other aspects, Hrytsenko’s campaign is very reminiscent of the Rada campaign in 2014, when he promised to establish a broad coalition of pro-European forces. In the end, though, he only managed to join forces with Vasyl Hatsko’s Democratic Alliance. This time, Hrytsenko also negotiated actively to form a coalition, but so far, the key potential partner, Lviv Mayor Andriy Sadoviy, has decided to run separately. Indeed, Hatsko supported Sadoviy. Some changes have taken place in Hrytsenko’s views of the powers that should belong to the Head of State. During the debates in 2014, he stated that the presidency needed to have some functions removed, including the appointment of candidates in the enforcement agencies. The 2018 Hrytsenko is definitely against any reduction in the powers of the country’s top executive and is now promoting the idea of a “strong hand.”

The bronze medal in the previous presidential race, much to the surprise of many, went to Oleh Lyashko. Thank to his campaign, it’s possible to track the main issues that bother Ukrainians at various points in time at least as well as by reading opinion polls. And the country’s top radical continues to promise to fix it all. In 2014, Liashko was the only candidate to use the occupation of Crimea in his campaign advertising. When asked how to return Crimea to Ukraine, during the debates he answered: “Fight for it. In every way possible: economically, diplomatically, and militarily. We gave Crimea away without a singe shot. I was the only candidate that called on us to fight for Crimea and I was labeled a provocateur. We could even engage in partisan warfare. And, of course, the main thing is the economy. When Crimeans start to live poorly, they themselves will ask Ukraine to take them back.” He went on to say that to get Crimea back, Ukraine just has to wait 3-7 years: “Putin will leave, the government will fall apart. Chechnya and Dagestan will start asking again, ‘How come Crimea can and we can’t?’ This is what we will take advantage of, when they become weak.”

Today, the leader of the Radical Party is promising Ukrainians low utility rates, high pensions and wages, and a rejection of IMF loans. Still, Lyashko will have a hard time repeating his 2014 success in 2019 – if nothing else because plenty of rivals have appeared in his domain.

The main contenders for the presidency in the previous election were Petro Poroshenko and Yulia Tymoshenko. Chances are quite high that it will be the same this time around, although their starting positions are very different today. The incumbent won in 2014 based on an entire slew of factors. Partly it was demand for a new face, which is still the case today. Although Poroshenko had been active politically since the late 1990s, he had never been the leader of a ranking political party. He was a successful businessman who was associated with order and decisiveness. After the events on the Maidan and the start of war, this was sorely lacking in Ukraine. The third component of his successful run was the withdrawal of Vitaliy Klitschko in his favor. The result was a resounding victory in the first round of voting.

The situation today is far more difficult. Firstly, Poroshenko has to pay for unfulfilled promises from 2014, including selling his business and quickly ending the Joint Forces Operation. For the latter, he has publicly apologized to the country. But placing Roshen in a blind trust instead of selling it, because the price he was offered was a quarter of its market value, has not satisfied many Ukrainian voters. But that’s not the most important point. Poroshenko’s main slogan in 2014 was “Living a new way.” As clear and understandable as this slogan was at the time, it’s now working against Poroshenko. The slogan was so good that most Ukrainians have not forgotten it. Each of them gave the slogan their own meaning, but the main desire of most voters at the time was to reduce the level of corruption and punish the criminals sitting in the halls of power. These issues have not progressed much since then.

During the 2014 debates, Poroshenko also promised a fair judiciary within a year through lustration, but that process and the re-accreditation of judges still hasn’t been completed. On the other hand, Poroshenko said from the first that he was against the election of judges because that would not guarantee their honesty. Most of the problems with corruption and with enshrining rule of law were supposed to be resolved by the Association Agreement with the EU. At the time, Poroshenko was also skeptical of Ukraine’s ascension to NATO, but now is promoting it actively: “In its current situation, Ukraine will not be accepted into NATO because of territorial disputes,” he aid at the time. “The popularity of NATO has grown but the question of security should not divide the country. Today, we have prepared an agreement that should ensure the country’s security… I can see that, right now, the conditions necessary for joining NATO aren’t in place. Period…” What agreement Poroshenko had in mind at the time, he never explained.

The president has already listed his successes on his new billboards: “Army, language, faith.” Among his other promises from the 2014 debates are winning the Stockholm arbitration case and stopping deliveries of Russian gas, and decentralization. Given the repeated increases in gas rates, however, gas would have to be mentioned very cautiously. Poroshenko is also short of potential ranking allies. Much will depend, not only on whether short on experience, long on popularity Sviatoslav Vakarchuk and Volodymyr Zelenskiy become the “new faces” of 2019, but also whom they support in the election if they decide not to run on their own. And they are highly unlikely to plump for the incumbent right now.

RELATED ARTICLE: Crisis of Representation

The frontrunner at this point is Yulia Tymoshenko could have decided not to run in the previous election. Certainly, many in her circle tried to dissuade her in 2014. Back then, she campaigned quietly and tested the waters and only at the end did she present the slogan, “A strong leader for difficult times.” At the time, Tymoshenko argued her decision saying that politicians should not be spending money on advertising but on helping the army.

“I will speak briefly about all the platform and advertisements,” said Tymoshenko during the May 2014 debates. “Don’t bother reading them and don’t bother looking at all those ads. There have been hundreds of them. ‘I’ll listen to each of you,’ and ‘I’ll make everyone better,’” – at which someone shouted “And the Ukrainian breakthrough” – “we’ve heard it all. But just look at people’s lives and all. I mean the candidates running for president. Look what they have achieved in their lives and choose that way. Not long ago I was driving around and saw an ad for one of the candidates. It was a rotating ad and it had got stuck, so it read ‘The main goal’ and then ‘Buy a cat.’ That’s why I suggest that people not focus on this too much.”

And so the war continues, and so Tymoshenko’s billboards are everywhere. The Batkivshchyna leader keeps trying to play several fields at the same time. She’s a populist who would even make Lyashko blush, with promises that the price of gas would be halved. Her proposal to sell domestic gas to consumers is hardly new and was among her platform’s planks back in 2014. This is where the braided lady is very consistent. The high price for Russian gas in the contracts she signed in the past – that, she says, was the price of independence. As an interesting aside, when asked this awkward question back in the 2014 debates, Tymoshenko was only able to respond in her second attempt.

Today, Tymoshenko proposes a “New Course” of reform for younger voters.” The Batkivshchyna leader has managed to recover the positions and ratings she had in 2014 thanks to her never-ending criticisms of the current administration. With the other component, offering substance, things have not been quite so simple. Her “New Course” raised more jokes than support among young people. And so there are serious doubts that Tymoshenko will be able to increase her current level of support. On the other hand, given the problems faced by her main rival, maybe she has enough as it is.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook