Still four months to the presidential election and campaigns are going full steam. True, ratings are pretty low, even for the frontrunners, so getting voters on their side will not be easy. Worse, it is increasingly more difficult to use tried and true political strategies under the current circumstances.

Permanent political oscillation

The period of historic uncertainty that lasted throughout virtually all of Ukraine’s years of independence was very convenient for elections. At first, Ukraine swung between desovietization and the conservation of the remains of socialism. Later, it vacillated between decolonization and Russki Mir. The lack of a clear response from the government to the most fundamental questions – not just on language and history, but on the country’s basic mode of existence – fuelled tensions that fed demand for varied political solution. The political environment formed its own structure and all candidates had to do was take their place on one side or another of the ideological barricades. Without established doctrines, any and all positions were strictly opportunistic.

In 1991, Leonid Kravchuk, an ex-nomenklatura ideologue, was challenged by national democrat Viacheslav Chornovil. In 1994, Chornovil’s voters supported Kravchuk against Leonid Kuchma, who was playing up to the pro-Russian electorate. But in 1999, they changed sides again, supporting Kuchma against the radically pro-Russian Communist leader, Petro Symonenko. The 2004 and 2010 elections followed a similar course. Rival candidates grew their ratings through mere opposition to “the other guys,” not burdening themselves with developing solid platforms and filling any gaps in substance with the standard clichés of populism.

The Euromaidan began as the next stage of the perennial standoff, which should have led to the next round of scheduled elections or even a snap election, with the by-now standard candidate from the national democratic opposition running against the Party of Regions – read pro-Russian – candidate.

RELATED ARTICLE: Iryna Bekeshkina: “We’ve never had this kind of existential political crisis before”

Instead, the Yanukovych regime collapsed, taking down the Party of Regions with it. Having no strong antagonist now, yesterday’s opposition politicians were forced to compete among themselves. The annexation of Crimea and the occupation of the Donbas turned the 2014 race into competition for the role of the leader who would bring Ukraine back to peace and security.

Since then, the situation has changed again. Pro-Russian forces have recovered from their humiliating rout and can expect better results in the upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections. A complete comeback still seems far-fetched, however, although they do have an audience in southern and eastern Ukraine and could well increase it somewhat, without their base, now in occupied Crimea and ORDiLO, their chances of repeating the success of 2010 are extremely small.

Wanted: Snap solutions

All this will make it impossible to apply the standard old election battle plans, so the 2019 presidential election will be a competition among candidates with “patriotic” platforms and no obvious ideological opposition – at least in the eyes of the average voter. The two top candidates will most likely share the same position on NATO and the EU, Crimea and the Donbas, and on the status of the Ukrainian language. In short, it won’t be enough to be “one of ours.” They will have to offer more specific answers to the most problematic issues. Unfortunately, there are no easy, meaning electorally useful, answers to offer.

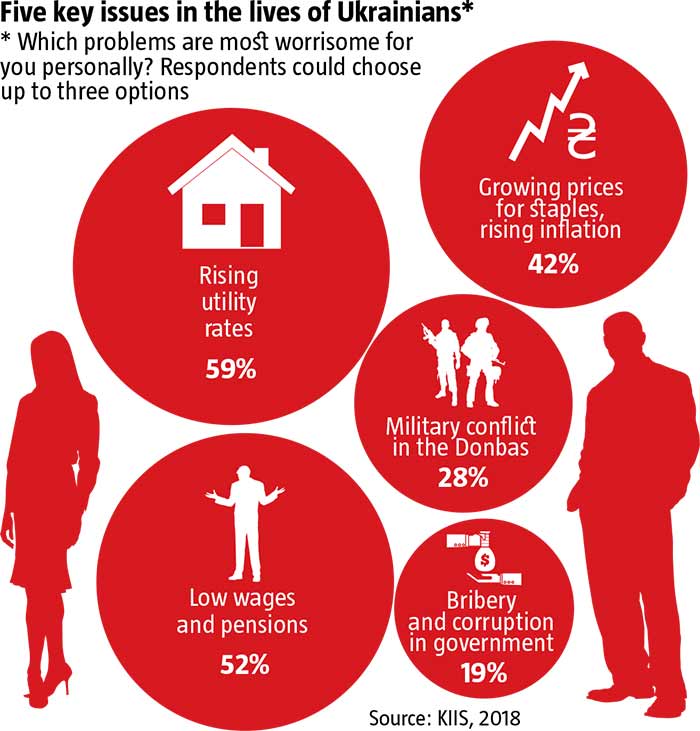

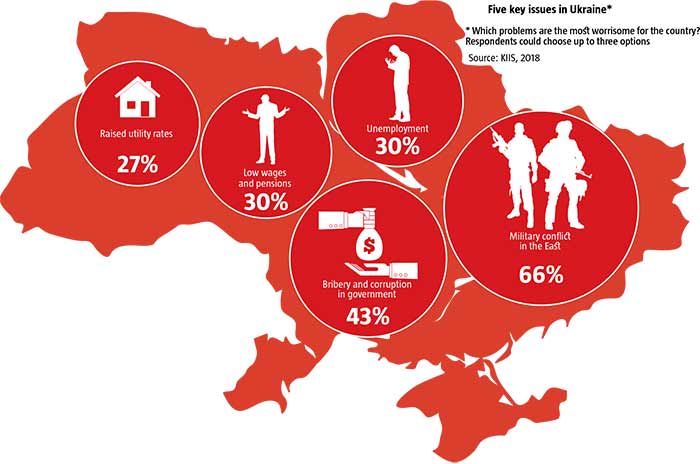

What are these issues? According to a fall 2018 Kyiv International Institute of Sociology poll, 66% of Ukrainians see the war in the Donbas as the most urgent issue, followed by corruption in government (43%), unemployment (30%), low wages and pensions (30%), and growing utility rates (27%). Among problems that affect them personally, this poll showed that 59% of Ukrainians were affected by rising utility rates, 52% by low wages and salaries, 42% by rising prices and inflation, and only 28% by the war, 19% by corruption in government and 18% by unemployment. Obviously, none of these issues has a quick, painless and effective solution. The return of Crimea and the liberation of the Donbas is a formula with too many unknowns. This makes it impossible for any candidate to guarantee a positive result here, especially something attainable within a single term in office. The switch to market energy prices is an objective necessity, although surprisingly many Ukrainians are unaware that it was also a condition for receiving IMF and other donor funds. Low pensions are a natural outcome of a nigh-bankrupt pension system – something that most developed economies have been struggling with for decades. Wages and employment reflect the domestic economy. Eliminating corruption is equally difficult, even with maximum of political will applied, because the political leadership depends on consensus with the oligarchic elite.

In theory, a strategy focused on an open, serious discussion of pressing issues could be the key to success in elections, and the candidate applying this approach would stand out among all the populists promising easy solutions and snap results. In Ukraine, however, this is likely to end in the opposite result, at least in the presidential race. When it comes to reforms, most Ukrainians want quick results. In a spring 2018 survey by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation, only 33% said they were ready to tolerate a declining quality of life for the ultimate success of reforms, and of them only 24% were prepared to tolerate this for up to a year. Most of the rest, 62%, could or would not tolerate it whatsoever. Although socio-economic matters are mostly the purview of the Government, not the president, voters don’t really distinguish between the two, simply blaming “those in power” in general, and personifying everything around the individual in the president’s seat. Since candidates for president cannot possibly avoid socio-economic issues, they have to resort to populism to hang on to their hard-won electorate. The current ratings show that this election will be a battle for every single ballot.

Moreover, candidates will have to compete both for the supporters of reforms and for its opponents – of which there are quite a few in Ukraine. This second group is being actively targeted today by ex-Party of Regions players, but pro-Ukrainian candidates will need to reach out to both groups or at least not scare away those who prefer stronger government support rather than reforms. Right now, these Ukrainian voters constitute an absolute and growing majority. A 2018 Democratic Initiatives poll showed that the number of Ukrainians expecting maximum free public services had grown from 62.7% to nearly 65% over 2017-2018. The share of those who were against this shrank from 23.5% to 22.6%. In addition to this, more progressive Ukrainians are adding pressure on those in power to ensure that Ukraine stays the European course and does not play at socialism. What makes the situation so dramatic is that nobody is likely to be elected, that is, to have the power to conduct European reforms, without being willing to play up to voters.

Ukraine thus finds itself in a paradoxical position, where to get an anti-populist platform implemented, candidates have to campaign using populist slogans. But this just scratches the surface of the problem. While effective election-time populism can bring a candidate to power, it also lays a bomb under their future ratings. The higher the bar of social expectations is raised, the faster disappointment will come, and the more vulnerable the future president will be. Those who use populism as a necessary election tool, but don’t try to carry out fantastic promises by following in the footsteps of Tsipras, Maduro or any other “champions of the people,” are likely to find themselves in the worst situation down the line.

Populism is a trap, not just for candidates for office but for the entire society as well. The electorate gets used to the idea that this is the style of communication politicians use and becomes deaf to the serious open discussion of issues. For irresponsible politicians, this works perfectly well, but Ukrainians became vulnerable to populism due to a totalitarian legacy amplified by the lack of vibrant democratic traditions. The soviet period imprinted in the Ukrainian collective mindset an image of those in power as virtually omnipotent holders of the key to life and death, not just material wealth. Because of this, the mechanisms of democracy that Ukrainians suddenly found themselves with came across, not as a way to articulate and bring to life their own interests, but as a tool for replacing the current god with someone hopefully more generous and sympathetic towards them. These unspoken illusions, rather than socialist beliefs, lie the root of Ukrainian paternalism. It is born where lack of faith in their own power meets trust in the omnipotence of those in power. Forced to fight for the votes of millions, politicians try to meet their electorate’s expectations rather than to re-educate it, by pretending to be “the one who can make life better today” with a flick of the presidential wand.

As Ukrainians develop their skills in engaging in real democracy and civic society, the appetite for populism will fade, although no nation is fully immune to it. The best-case scenario for today is: whoever comes to power in Ukraine in 2019 is prepared to play a double game: to apply populism and play on paternalistic expectations to gain power, but then to rely on the proactive minority to carry out painful reforms and maintain stability throughout the transition period. That minority is comprised of those Ukrainians who are willing to endure economic hardship for the sake of the future.

RELATED ARTICLE: Crisis of Representation

Still, the worst-case scenario seems far more likely: the newly-elected administration bases both its campaign strategy and its post-election policies on populism. This might deliver good-looking symbolic gestures and loud but empty announcements at best, and ill-considered steps such as an irresponsible increase in pensions and the minimum wage, at worst. In the worst-case scenario, the new government will try to walk back the reforms that have been launched so far, in the hopes of buying voter support. This could deliver some short-term results, but the long-term impact will be difficult – not the least because 46% of Ukrainians will think that an increase of their household income is the first signal of irreversible positive changes: the share of such people grew from 35% to 46% over 2015-2017, according to a 2017 GfK survey. Inflation is one way to deliver this “improvement.” even if short-lived. Given this gloomy prospect, one can only hope that the political forces capable of such adventurism care less about implementing their election promises than their rivals.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook