Despite hopes of another chance to completely reboot the country after the second revolution Ukraine is slowly entering the second round of squabbles within the once uniform Orange team. The leaders of the current presidential campaign are bringing back the groups of “Yulians” (after Yulia Tymoshenko) and “Victorians” (the former team of Victor Yushchenko, now embodied in “Petrorians” after Petro Poroshenko), almost identical to those from the post-Orange Revolution years of 2005-2009. When Viktor Yushchenko was President and Yulia Tymoshenko was Premier, they had waged a deadly struggle against each other instead of reforming and strengthening the country.

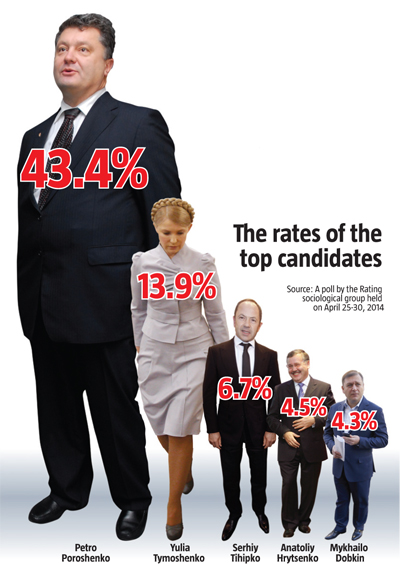

In the current campaign, the top three leaders have been unchanged for a while now. According to a survey by Rating, a sociological agency, held on April 25-30, Petro Poroshenko enjoys the support of 43.4% of those polled. Yulia Tymoshenko has 13.9%. Serhiy Tihipko, Anatoliy Hrytsenko and Mykhailo Dobkin would get 6.7%, 4.5% and 4.3% respectively. However, when GFK Ukraine held a survey on May 6-8, it revealed a surprising result where Tymoshneko’s rate was much lower and Tihipko’s was much higher. As a result, it would be Serhiy Tihipko, not Yulia Tymoshenko, with the best chance to run against Petro Poroshenko in the second round.

Two important facts to know about GFK Ukraine’s data are that the poll was held via telephone exclusively, and its predictions were always the farthest from the actual results compared to all other sociological services in Ukraine in previous elections. This is probably because GFK Ukraine does not cover the entire electorate in villages and small towns whose citizens account for nearly half of all voters in Ukraine. And Tihipko always had better rates in big and mid-sized cities, while Tymoshenko’s core electorate was in rural regions.

The names of the final pair in round two may change given the fact that only 37% of those polled claimed that they were “sure about their choice” in the latest survey by Rating. Another 33% said that they “were sure but their choice could still change”. Tymoshenko and Poroshenko have the most confident voters – 54% of their supporters were confident about their choice. 12% of those polled have not decided on their preferred candidate yet.

However, it is other figures that look worrisome. If Poroshenko and Tymoshenko get to the second round, only 14% of the Donbas citizens are prepared to vote for any of them. Two thirds insist that they will ignore the vote with these two candidates in the second round, essentially boycotting it. 22% are still contemplating their choice for the second round. No other region in Ukraine has such extreme sentiments. Only 35% will ignore the vote in Kharkiv, Dnipropetrovsk and Zaporizhia Oblasts if these two candidates make it into round two, while 47% will not vote in Southern Ukraine. This could undermine the legitimacy of the election in Donetsk region and provide tools for speculations.

RELATED ARTICLE: The National Reserve: The background, nature and threats of the Donbas identity

Despite the widespread Russian propagandist mantra about the government monopolized by Western Ukrainians, all top candidates come from Southeastern Ukraine. Petro Poroshenko was born in Odesa Oblast; Yulia Tymoshenko comes from Dnipropetrovsk Oblast; Serhiy Tihipko used to live in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast as well, and Mykhailo Dobkin comes from Kharkiv.

The common and the different in the platforms

The platforms of two top candidates in this campaign look attractive for the wide audience yet they do not fit in the scope of powers the current Constitution grants the President.

Yulia Tymoshenko openly claims her “will for power” and intentions to concentrate it in order “to break the current system”. Petro Poroshenko speaks of the opposite, pledging to “become a guarantor of the newly reinstated parliamentary system… while not claiming powers that exceed the ones I am elected for”. Meanwhile, people who talk to him in person insist that his aspirations for absolute power are identical to, if not stronger than those of Tymoshenko.

Tymoshenko’s platform offers more populism that pops up in some mutually-exclusive promises. For instance, she pledges to extend moratorium on farmland sale while ensuring the opportunity to sell state-owned farmland at the market price (which cannot be estimated without the land market). She also offers an inflated annual lease price of 10% of the farmland market price (which, again, is impossible to calculate in a non-existent farmland market).

Another pledge in her platform is to abolish special pensions and privileges for all top officials. This is, however, forbidden to do for the pensioners who are already getting them. Tymoshenko is promising to ban fines for late utility payments “until welfare rises significantly”. This will result in arbitrary debts on utilities and gas, deteriorating utility services, increasing burden on the budgets of all levels, and, eventually, a situation where disciplined pensioners will keep paying for the wealthy judges delaying payments yet confident of their impunity.

Petro Poroshenko is trying to distance himself from social populism, a trademark element in his key rival’s campaign. He claims that “all political platforms you have seen before were about pennies from heaven but they never come down” and “clearly, I support the rise of wages, pensions and student scholarships”, but “we will spend money on all this as soon as we have it once we have built a new economy”. Meanwhile, Poroshenko’s platform suggests that he expects to transfer responsibility for the social-economic situation in Ukraine on the government, the one in charge of “running economic processes” under the current version of the Constitution. As a guarantor of the Constitution, rights and freedoms, the President should only “create conditions” for social justice and innovative economy, Poroshenko believes.

If he indeed does not intend to expand his powers, he and his Administration will obviously act as expert observers who “evaluate and instruct” the government “responsible for running economic processes” and the parliament responsible for passing laws. When Yushchenko did that as President after the Orange Revolution, he faced harsh criticism from the Party of Regions, then in opposition, and from the majority of Ukrainian society that votes for the President and expects him to ensure full-scale transformations (voters don’t care how he does that), rather than to merely advise to the parliament and government which turn out to be the bad cops.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Vacuum in Luhansk Oblast

Thus, just like with Yushchenko, Ukrainian voters will soon inevitably see the President as someone responsible for the state policy. His attempts to criticize the government or the parliament for ineffectiveness will most likely fuel another round of deep disappointment: the voters will interpret this as just another series of internal squabbles in “the single democratic pro-European team”. This will discredit Poroshenko and Ukrainian statehood overall, thus playing into the hands of pro-Russian forces and the Kremlin’s policy to subordinate Ukraine.

Cognitive dissonance

Both Tymoshenko and Poroshenko support lustration and elimination of corruption in the state bodies, fair courts, honest law enforcers, lower tax pressure on the business and demonopolization of the economy. Meanwhile, both groups are being staffed with representatives of the former government. Poroshenko has been criticized multiple times for actively engaging people from the tandem of Serhiy Liovochkin, Party of Regions MP and ex-Chief of Staff under Viktor Yanukovych, and Dmytro Firtash, the gas tycoon recently arrested in Vienna on FBI warrant, in the regions. Tymoshenko’s Batkivshchyna party voted in unison with the Party of Regions on acts that were not supported by the rest of the democratic coalition in the post-Maidan parliament. Svoboda members have blamed it for attempts to provoke their exit from the coalition so that the Party of Regions could replace them. As to oligarchs, Rinat Akhmetov seems to be the most interested one in Tymoshenko’s presidency now, given his difficult record with Poroshenko in the past. So is Ihor Kolomoyskyi, the Dnipropetrovsk-based oligarch and owner of Privat Group, who is now actively gaining political weight under the rule of Tymoshenko’s allies as interim government.

The most concerning aspect is obviously the Russian trace. Poroshenko is said to engage people related to Viktor Baloha and Volodymyr Lytvyn, Andriy Derkach and Dmytro Firtash. The latter two were always the key Russian lobbyists in Ukraine. Yulia Tymoshenko on her part has always been on good terms with the agents of Russian influence in Ukraine, such as Viktor Medvedchuk, his right-hand man Nestor Shufrych, Andriy Kliuyev (ex-Chief of Staff under Yanukovych), and Tymoshenko’s one-time main advisor Andriy Portnov (ex-First Deputy Chief of Staff for Yanukovych). Acting President and Tymoshenko’s ally Oleksandr Turchynov is known to have actively negotiated with Vadym Novynsky, Putin’s “supervisor” in the Ukrainian parliament and business partner to tycoon Rinat Akhmetov. It is Tymoshenko’s allies who were mostly blamed for the lack of adequate actions to restrain Russian aggression in Crimea and the Donbas in the first month after Yanukovych fled.

The recent deadly incident in Odesa adds to the Tymoshenko controversy: MP Oleksandr Dubovyi, close to Tymoshenko and Turchynov, is said to have been involved in covering up separatist groups and making sure that police chiefs avoided responsibility for helping or doing nothing to hold back separatists. Ex-governor of Odesa Oblast Volodymyr Nemyrovskyi and ex-Interior Minister Yuriy Lutsenko have both blamed him for lobbying the appointment of the traitor police chiefs, Dmytro Fuchidzhi and Oleh Lutsiuk. On the other hand, Poroshenko raises doubts as his plants resume operations in Russia and his business operates uninhibitedly in the Russian-occupied Crimea. Some refer this to his deals with Firtash whose efforts in lobbying Putin’s interests became obvious from his clearly pro-Russian stance during the EuroMaidan.

Tied by hesitation

Both top candidates have similar approaches to the language issue, and these approaches will do nothing to consolidate the nation or overcome the regional divide. Yulia Tymoshenko promotes Ukrainian as the only state language with Russian and other languages having the official status in the regions where the dominating majority wants that. This will subsequently lead to increasing Russification of a number of regions in South-Eastern Ukraine. Petro Poroshenko pledges to preserve the current status quo on the language issue, which means that the Kolesnichenko-Kivalov language law will stay intact in its current version.

None of them is prepared to take steps to protect Ukrainian-speakers from Russification in Southern, Eastern and partly Central Ukraine, let alone facilitate the actual rather than formal use of Ukrainian as the state language. Eye-witnesses claim that both Tymoshenko, and Poroshenko, as well as their families, speak Russian at home and in private life while switching to Ukrainian in public or to talk to the people they find useful.

Both candidates promise to facilitate Ukraine’s defence capacity and European integration. Yet, none mentions NATO membership in their platforms. Poroshenko, as the most likely winner of this campaign, seems only willing to follow the crowd on the issue of NATO as the only way to guarantee Ukraine’s security in the face of continuous Russian threat, and even accept the veto of the pro-Russian fifth column in Southeastern Ukraine. Apparently, he will be the first one to lead Ukraine to NATO as soon as 70% of Ukrainians support the idea. When the share is 30%, he will not since he would thus risk losing Donetsk or Luhansk Oblasts, Kharkiv or Odesa.

Instead, both candidates offer useless options to replace NATO membership. Tymoshenko suggests an amorphous “European policy of common security”, while Poroshenko offers a reinforced version of the Budapest Memorandum. Both support elimination of any aspect in which Ukraine depends on Russia, energy being the top priority. Meanwhile, both support friendly, equal and partner relations with the “future non-Putin democratic Russia” which is hardly an option at all.

Both Tymoshenko and Poroshenko pledge to abolish local state administration and to delegate most of their functions to executive committees of local councils. In the current situation, however, this can only further fuel separatism and restrict ways for the central government to affect inefficiency in the regions. If implemented, this will hardly liberate the central government from responsibility for local problems, as Poroshenko expects in his platform, since most Ukrainians remain paternalist-minded, especially in Southeastern Ukraine. They will keep blaming the chaos in their towns and villages on the incapable central government. That will allow local authorities to fuel such sentiments via their loyal local media, while Russia will use this to aggravate pro-Russian sentiments.