If someone asked you to build a successful country, what would you start with? Some would decide to unite all its citizens around a common goal, because such a nation will freely wade any sea and tackle any challenge without problems. Others might try to change the mentality of their fellow citizens, because successful people make a successful nation. Someone else would firstly build an effective system of social relations that would open up the potential of every person, turning the sum of individual achievements into the success of the entire nation. Another might try to make use of the competitive advantage of the country’s soil, using this foundation to develop a powerful agricultural sector on a global scale…

Each of these ideas has some sense to it. Yet not one of them can be achieved in its pure form, as Ukraine’s experience has demonstrated. In 2014, after the Revolution of Dignity, Ukrainians were faced with the challenge of building a successful country. To do this, reforms were launched in a dozen different areas. Four years have passed and right now we can confirm that the transformations are far from what might be desired in many spheres. Only those reforms where all the necessary factors—progressive people united by a common goal and ready to change and be changed, an effective coordination system, a sector that was ready for transformations—were in place can now be called successful: when the right components are in place, even the most depressed sector can be transformed into a leading one.

RELATED ARTICLE: Russia’s Azov blockade. How the Kerch bridge built by Russia blocks and threatens the ports in Mariupol and Berdiansk

Reforming the most surprising sectors

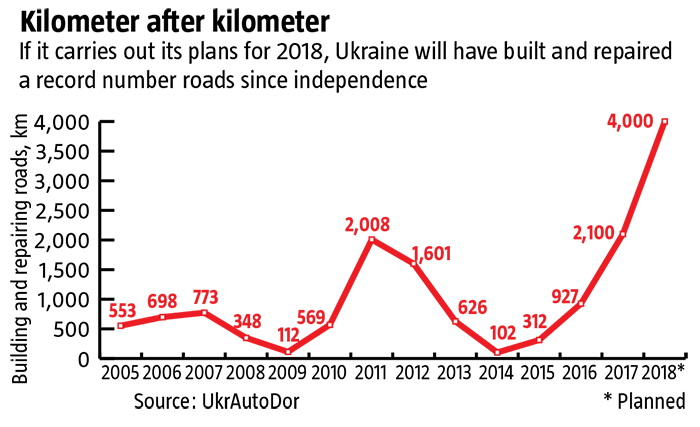

Among such sectors in Ukraine is the roadways management system. Considering where it all began, this is hard to even imagine. When the Revolution of Dignity was taking place, this sector was in a pathetic state. In 2013, UkrAvtodor, the state roadways corporation, gobbled up UAH 15.5 billion, 40% of which went to service and pay of debts that had been incurred for the Euro-2012 football championships, while the rest went to build and repair all of 626 km of roads (see Kilometer after kilometer).

Among such sectors in Ukraine is the roadways management system. Considering where it all began, this is hard to even imagine. When the Revolution of Dignity was taking place, this sector was in a pathetic state. In 2013, UkrAvtodor, the state roadways corporation, gobbled up UAH 15.5 billion, 40% of which went to service and pay of debts that had been incurred for the Euro-2012 football championships, while the rest went to build and repair all of 626 km of roads (see Kilometer after kilometer).

Four years later, in 2017, UkrAvtodor spent a larger budget, UAH 20.2bn, of which only a quarter went to cover debts while more than 2,100 km of roadways were repaired or rebuilt. Spending on road construction grew 78%, while the amount of repaired and new roads increased nearly 350%. And this was despite the fact that the dollar, to which the cost of a significant part of the materials and equipment needed for this work is tied, tripled in value compared to the hryvnia during this time. When numbers are compared, it becomes clear just how corrupt the roadways management system was and how much it has changed since then.

Indeed, the roadways corporation was so corrupt that only the blindest of the blind was not aware of how much theft was involved during the construction of roadways. Materials were stolen brazenly and at all levels: it was enough to just look at the kitschy palaces of the directors of petty county roadworks to understand where it was all going.

Analysts were predicting that, under the circumstances, it would take decades to resolve all the problems the sector was facing. They were convinced that there was no point even thinking about quality road in Ukraine at this time. Indeed, it was hard not to agree with them. Only a handful of individuals were of a different opinion, united by a common vision with a ready concept for reforming the branch, and prepared to act, the minute the right circumstances appeared. When the Revolution of Dignity took place, they saw a chance to bring out and carry out their idea. The result is evident: the situation in Ukraine’s road construction is radically different and the sector has confidently transformed itself from an outsider to a leader.

Pulling up from behind

Maybe it’s for the better that Ukraine suffered through a terrible economic crisis over 2014-2016. Its budget had almost no money at all for roads, which offered a painless opportunity to institute new principles for the sector to function, means to avoid corruption, to polish a new system based on very limited funding, and to prepare the base for a qualitative leap. According to Slavomir Novak, the acting director of the State Agency for Roadways in Ukraine or UkrAvtodor, all procurements have been handled exclusively through the ProZorro system for over a year. Thanks to this, the economies have been remarkable, and if we compare the results of roadworks in 2013 and 2017, the difference is striking: foreign companies have entered the market, competition has appeared in the sector, and the quality of the work of Ukraine’s roadworks teams has gone way up. Working in the sector has suddenly become prestigious again.

RELATED ARTICLE: Light at the end of the tunnel. Where Ukraine’s banking system is moving

A new system was also set up to support the quality of execution. According to Novak, the guarantee for standard repair work is at least five years, while complete reconstruction is guaranteed for at least 10. If an expert review determines that work was not done to the necessary quality level, the contractor will have to eliminate all the flaws at its own cost according to the new contracts. This gives reason for UkrAvtodor management to feel confident in the quality of the roads that were repaired last year.

Qualitative changes in the sector have also had an impact on roadworks personnel themselves. Possibly it’s too soon to draw conclusions, but they seem to have become more confident in tomorrow’s day and have been mobilizing resources. At the end of 2017, local employees of UkrAvtodor confirm that they have enough resources accumulated to increase the scale of road repair and construction severalfold. It’s just a question of the volume and regularity of funding.

Getting smart about funding

Until not long ago, funding was not an easy question. Last year was the turning point. According to Treasury figures, the state budget allocated UAH 15.2bn for roadway infrastructure. Initially, plans were to spend over UAH 10bn more, but money from an experimental customs program, whose surplus revenues had been the main source of funding for road repairs after the Revolution, came in at a far lower rate. As a result, by mid-December 2017, plans for road repair and construction had only been fulfilled at 68%, according to the Ministry of Infrastructure. Local roadworks managers unanimously began to declare that there was not enough money and that increasing the scale of the works made no sense. The problem needed a radical solution.

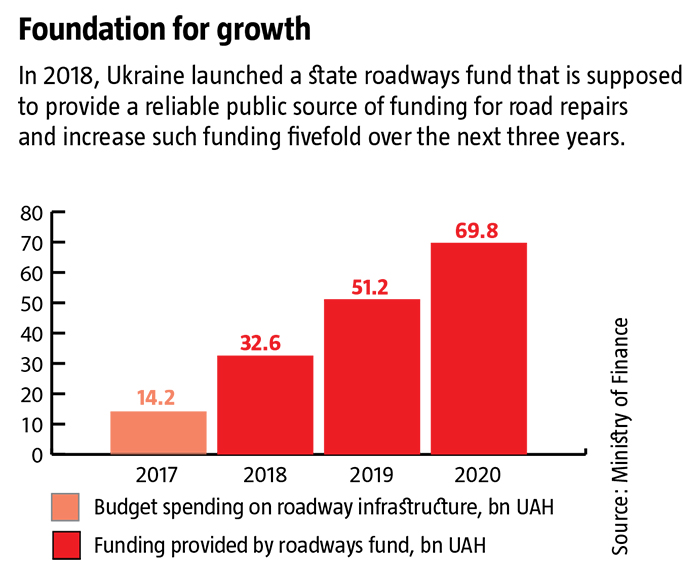

Nor was it long in coming. In early 2018, the Roads Fund began to operate. This is a budget fund that accumulates revenues to the Treasury that are related to the vehicular sector and directs them entirely at repairing and building roadways, and increasing road safety. The Fund is supposed to gradually accumulate capital. This year, 50% of revenues from excise taxes on fuels and vehicles made in Ukraine or imported from abroad, and duty on petroleum products, vehicles and tires will be directed to the Fund. In 2019, this share will increase to 75%, and in 2020, fully 100% of these budget revenues will go to the Fund. In the future, the Fund will also receive funding from international donors, tolls, and fees from transferring roads to a long-term leases or concessions.

RELATED ARTICLE: How Ukraine can prepare for a probable termination of Gazprom's gas transit through its system after 2019

The Government expects these sources of state funding for road building and repair to grow to nearly UAH 70bn by 2020 (see Foundation for growth). Even in the current year, major funding has been planned:  the Roads Fund will see around UAH 47bn come in, of which UAH 33bn will come from the budget and the remaining UAH 14bn from international donors. This kind of financial resources allow roadworks managers look confidently to the future and plan for many years ahead, something that is very much needed now, because there’s plenty of work for everyone.

the Roads Fund will see around UAH 47bn come in, of which UAH 33bn will come from the budget and the remaining UAH 14bn from international donors. This kind of financial resources allow roadworks managers look confidently to the future and plan for many years ahead, something that is very much needed now, because there’s plenty of work for everyone.

Notably, the Cabinet has established a special procedure for distributing the money in the Roads Fund: 60% of all revenues will go to maintain and build about 47,000 kilometers of national roadways, and 35% or UAH 11bn will go to local roads. 20% of the funding for local roads will go to maintain streets and roads belonging to communities within the limits of population centers—about 250,000 km—and the rest will go to local highways between population centers, about 123,000 km. This places the accent on national roadways, which means that, in the not-too-distant future, Ukraine should find itself covered with quality road connections.

Doors and corridors

The new set-up means that already this year plans include almost double the length of roads that will be repaired or rebuilt, bringing the total up to 4,000 km in 2018. This gradual accumulation of funding offers the conditions necessary not to stop at this indicator but to raise annual roadworks to 10,000 km, which means that at least half of Ukraine’s highways will be redone in the next decade. UkrAvtodor has already set an ambitious goal for itself: to connect all oblast centers with quality roadways over the next five years. If it succeeds, it will change the country visibly for the better once and for all.

Quantity is already switching to quality. Last year, the GO Highway project was presented, which plans to link Ukraine’s Black Sea ports and Poland’s Baltic Sea ports with a high-quality highway. This is actually not repair work but the massive construction of new highways. Ukraine has never seen anything like this before, but the first results should be in by 2019. This project will considerably increase Ukraine’s appeal as a transit country and fits well with the “new Silk Road” transport corridor from China to Europe, bypassing Russia.

RELATED ARTICLE: Deputy Finance Minister Oksana Markarova on 7 steps to a new bank strategy for Ukraine

But this is not all. Right now discussions are taking place in the EU over a “European Plan” for Ukraine, similar to the Marshall Plan that helped Europe recover after WWII, to provide Ukraine with up to €5bn a year for development projects. The key bottleneck, say the Europeans, is Ukraine’s poor capacity to use funding effectively. There’s some truth to this, because the Infrastructure Ministry says that last year the country took only 38% of the allocated funds proposed by IFIs for road construction. In other areas, indicators are even worse.

Once the country proves its capacity to build quality roads with a minimum of corruption involved and western funding begins to stream its way, even more funds will be available for roadworks. The Europeans are interested in this, from both a business perspective and a political one. In the last few years, there has been a stable tendency for Ukraine to be included in European production chains. Factories are being launched that manufacture, say, spare parts for German cars, and they need good links to industrial centers in Europe. Europeans understand this and so they will likely support and lobby for the building of good roads in Ukraine. So far, this only concerns western Ukraine, but the trend should continue and gradually expand to the rest of the country. EU support, especially financing, will make it possible to increase road building severalfold.

Building more than roads

Although the situation in Ukraine’s roadways management system is cardinally different from what it was prior to 2014, it’s important to understand clearly all the consequences of large-scale highway construction. Potentially, there are quite a few of them.

First of all, good roads mean that transport and transit potential can be realized, which already means considerable economic dividends. For one thing, enormous resources have to be mobilized to build roads, which means hundreds of thousands of jobs, because it affects not just the roadworks system but also related sectors, such as the production of gravel, sand and asphalt, the manufacture of heavy equipment, and fuel processing. Once the road opens, tens of thousands of other jobs are generated in eateries, hotels and motels, gas stations, shops, and so on. A country with good roads can take on considerable transit and tourist streams from neighboring countries and make considerable capital out of it.

Secondly, good roads bring people closer together. They reduce the distance from the most distant corners of a country and the most isolated social groups. Many of us have seen the statistic that most residents of Donbas had never left their region, which led to the closed mentality of the region—and the consequences are with us to this day. With good roads, travel becomes much more accessible, and Ukrainians spend more time communicating, exchanging thoughts, ideas, and life experiences with each other in various parts of the country. What is most needed to shape the Ukrainian nation if not contact with each other?

RELATED ARTICLE: Ukraine, like you’ve never seen it before. How a volunteer project explores and transforms the country

Thirdly, large-scale road-building rallies the public. Everybody needs roads, without exception, and their condition in Ukraine has bothered everybody. If roads begin to be better quality, this will lead to more upbeat conversations, positive news reports, and growing public faith and trust in the government. The wide broadcasting of the road-building process will draw the attention of millions and inspire them. This, too, could become a unifying factor for Ukraine.

Fourth, expanding networks of quality highways could be the country’s first successful national project. For Ukraine to be successful, every Ukrainian needs to learn to be successful and that means having high quality examples and models that millions can draw inspiration from. Right now, such examples are lacking, so Ukrainians need to work together to create them. Building good roads is a very good option.

And finally, good roads are a factor in civilized identity. Building good roads is a great chance for Ukrainians to show themselves, first of all, that they are different, that they are not decaying.

The way Slavomir Novak puts it, in Poland, politicians won elections based on the roads they built. In Canada and the US, mayors are often re-elected for the same reason. Perhaps this will happen in Ukraine, too. In any case, it should motivate politicians to support the processes that are already underway. Of course, no one can guarantee that populists won’t carry the day at the next election, even as they eye the juicy budget roadworks are now getting, hoping to get their hands on public money once more and keeping the country on the same track to degradation. But it won’t be as easy for them: this sector is picking up pace and transforming itself from outsider to leader.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook