Ukraine is widely perceived as a predominantly urban country, with the rural population constituting a minority that lives in socioeconomic backwater on subsidies from the state. In the pre-Maidan Ukraine, the share of urban population was 69%, going down to 68% after the occupation of Crimea and parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts. However, reality is very different from official statistics and reveals a more complex problem.

By the share of agriculture in GDP, the structure of employment, or the share of people living in rural areas, Ukraine is increasingly becoming an agrarian country. On the one hand, this signals that Ukraine’s prospects depend more than we believe on solving infrastructural, social and economic problems in agriculture-focused areas. On the other hand, this proves that doing so in the traditional paternalistic way, when villages and agriculture were subsidized by cities and urban industry as in the Soviet Union, or as in rich Western countries with an insignificant share of agriculture and low density of population in agricultural areas, is impossible.

Solving the problems of agricultural areas should be primarily the project of their residents financed from their own resources. The role of the central government there should be reduced to creating conditions that would stimulate and facilitate it. The success, however, will depend entirely on the ability of the residents to become more active socially and politically. This would contrast with their long-lasting traditional hibernation and exceeded expectations placed on regional and national governments to address all local problems.

Specifics of urban Ukraine

Though the share of overall urban population in Ukraine has not changed officially in the recent years, there have been significant shifts between the shares of population in cities and towns of different sizes. Out of 52 Ukrainian cities with over 100,000 citizens as of 2014, 15 are in the territories occupied by Russia (6 in Crimea and 9 in parts of Donbas). These include 5 out of 13 cities with 300,000 to 1,000,000 residents. In the rest of the Ukrainian territory, the share of residents in major cities with the population exceeding 1 million (Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odesa) has grown. So has the share of people living in towns with populations of 20,000–25,000.

Estimates based on the current official statistics from the central and regional statistics bureaus show that, as of the early May 2015, the actual population of Ukraine (excluding the occupied territories) counted 39 million. This figure did not include IDPs from the occupied parts of Donbas since their number is impossible to determine precisely at the moment.

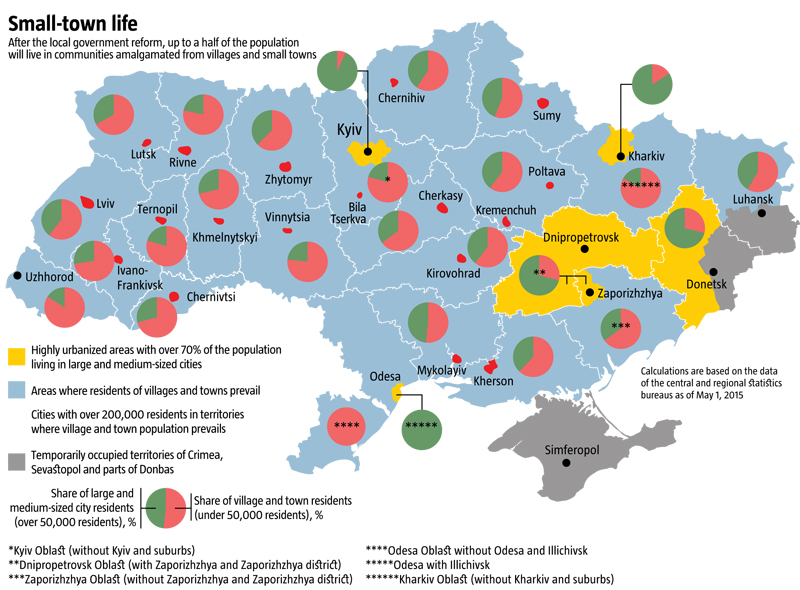

Out of these 39 million, 26.6 million officially qualify as city residents, and 12.4 million as the rural population. However, only 18.2 million of the urban population live in cities with over 50,000 residents (settlements below this mark qualify as towns). The shares of such urban population are very uneven throughout Ukraine: unlike the handful of compact hubs where urban population is concentrated more heavily, in other parts of the country its share is fairly low, ranging anywhere between 20 and 30%.

The population of these compact hubs totals 10 million. They include the “Greater Kyiv” that covers Kyiv, Brovary and Irpin and is home to 3.08 million residents; Prydniprovsky region including Dnipropetrovsk Oblast and the adjacent Zaporizhzhya and Zaporizhzhya district with 3 million; Kharkiv with 1.45 million; the “Greater Odesa" covering Odesa and Illichivsk with1.1 million, and the Ukraine-controlled part of Donetsk Oblast with 1.4 million people.

Beyond these hubs, the share of city residents (meaning cities with over 50,000 people) is a little over 28.3%. In most oblasts, this population is concentrated in oblast capitals (Vinnytsya, Ternopil, Chernivtsi and Rivne oblasts) and a couple more cities with populations of 50,000–100,000 in Zakarpatska, Khmelnytskyi, Volyn, Zhytomyr, Poltava, Ivano-Frankivsk, Kirovohrad, Mykolayiv and Kherson oblasts.

RELATED ARTICLE: Positive and negative results of austerity and painful economic reforms

Overall, with the abovementioned hubs excluded, urban population is distributed fairly evenly in the West (28.3%), South (30.9%), Center (33.1%) and East. For example, 27.5% of the population in the Ukraine-controlled part of Luhansk Oblast, live in cities with over 50,000 residents. The share for Zaporizhzhya Oblast and its suburbs adjacent to Dnipropetrovsk Oblast is 35%.

Thus, in most of Ukraine’s oblasts residents of towns with less than 50,000 populations prevail. This often distorts sociological surveys carried out by companies which focus on large cities only, even though the sentiments of residents in smaller cities in Central and Western Ukraine differ significantly from those in their oblast capitals, let alone in large and medium-sized cities concentrated in the above five hubs.

Towns and decentralization

67 of Ukrainian towns have over 20,000 residents rely on non-agricultural sectors: Ladyzhyn, Enerhodar, Netishyn and Slavutych have a well-developed energy industry; Fastiv, Kozyatyn, Zhmerynka are major transportation hubs; Myrhorod and Truskavets are popular tourist destinations. They have the total of around 2.1 million residents. The remaining 6.3 million urban residents live in standard small towns.

Back in the Soviet times, most towns had one or even two large agricultural enterprises (collective or state farms) with at least 1,000–1,500 employees. After the land reform, the employees were given land allotments that are either rented out or cultivated independently by their families today. Like the rural population, most residents of these towns have private housing and live off subsistence farming, while others earn their daily bread from farming businesses or agricultural firms established on the basis of former soviet collective farms (which often belong to agricultural holdings).

Over the past 20-25 years, however, most unsustainable local enterprises have gone out of business and towns have become increasingly similar to the large villages around them. In towns with a county center status, most jobs and gross regional product are generated by the state budget-funded public bodies and social infrastructure institutions (hospitals, cultural establishments, etc.). Today, these towns are in the best position to become centers of the newly-consolidated communities, a status that would enhance their agricultural profile and further ruralize the existing towns.

Such towns and villages today are home to over 18.7 million residents (48% of Ukraine’s total population). Cities with over 50,000 residents are home to 18.2 million (46.7%) people. Another 2.1 million or 5.3% live in the 67 cities that are in the stage of transition from towns to medium-sized cities. The latter in their majority will also become community centers integrating the surrounding villages, but they will have less of an agrarian component.

Many Ukrainians perceive the consolidation of rural communities (resulting from the decentralization reform) as merger of several former village councils into one. In reality, based on the new Government-approved Methodology for Capacities of Territorial Communities, it is current county or oblast capitals that will mostly be eligible for the status of community centers. Currently, Ukraine (except for occupied territories) has about 900 small towns and urban settlements. After decentralization, about 1,200-1,400 communities have to be established.

RELATED ARTICLE: Decentralization: The Wrong Solution to the Wrong Problem?

The infrastructure of a potential community center, in addition to secondary schools, polyclinics/outpatient departments, preschool and afterschool facilities, must include premises suitable for public and law enforcement agencies, as well as offices carrying out civil status and property titles registration, pension provision, social security, fire safety, and treasury services. According to the “accessibility criterion", community centers must be no farther than 20-25 km in paved roads from the most remote community settlement. This is comparable with the distance from the majority of current county centers to the most remote villages in the county.

According to the information obtained from the regions, at least in Central and Southern Ukraine where old administrative counties with small populations (15,000–35,000) prevail, there is a strongly marked trend to form communities based primarily on the existing counties. Splitting a county into two or more communities will most probably become an exception rather than a rule. This could be a case either in the counties with populations of or over 50,000 and/or having within them at least two or three towns or urban settlements, or in rather large counties with low population density, primarily in the steppe and forest areas, where establishing communities basing on old county structure would mean exceeding the prescribed distance to the center.

The attempts of local village heads in some counties to form small communities (five to seven in small counties) by combining only a few existing village councils are at odds with the government methodology and, not least, with the interests of the old county administrations, which could retain and even consolidate their authority over the territories they previously controlled if their county centers become the capitals of the newly-amalgamated communities. Therefore, any attempts to set up numerous smaller communities within existing counties are likely to eventually be stifled by the lack of public funding.

Challenges and opportunities

The growing share of agricultural communities in population structure and the increased size of those communities resulting from the merger of villages will bring about both new challenges and new opportunities for their residents.

On the one hand, there is a risk that large agricultural holdings and large local landowners will establish control over communities and povits, groups of communities. This can lead to the degradation of infrastructure and growing rightlessness of local residents that could be far worse than under the rule of oligarchs on the nationwide scale. If controlled by large landowners, local deputies, elected authorities and heads of executive committees, police and other bodies can bring life in rural communities much closer to feudal standards than it has ever been before. The prefect, an authority appointed by the central government and independent of local landowners, will also be very close (most today's counties will only have three or four povits) and have powers as wide as those of the present-day state administrations.

Another important aspect is that the residents of consolidated agricultural communities will gain importance as a powerful electoral resource in national and regional elections. They constitute a strong majority in most regions and provide at least half of the votes at the national level. Previously, they were traditionally used by public officials through administrative leverage. Now, especially with the growing weight of the agricultural sector and the holdings dominating it in Ukraine’s overall economy, the owners of these holdings may soon try to privatize their constituencies and, quite possibly, even create one or more agricultural political parties.

On the other hand, consolidation will boost small businesses within each community and povit (farmers, owners of small food and timber processing facilities, trade businesses, transportation and service providers). There will be at least hundreds of them in the new communities, and thousands in regions – the post-decentralization version of the current oblasts. This will provide comfortable environment for the growth of effective local economic and socio-political associations to promote their interests, solve pressing issues and exercise pressure on local authorities whom the community life will increasingly depend on.

RELATED ARTICLE: Transition from oligarch economy to EU membership for Ukraine

In particular, the alliance of communities may give a new impetus to farmers’ movement, who are primarily interested in countering the domination of agricultural holdings and landowners. This potential is particularly strong in regions with a developed farming sector. For example, Odesa Oblast has 5,200 farming enterprises, Mykolayiv Oblast has 3,900, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast has 3,300, Kirovohrad Oblast – 2,600, Kherson Oblast – 2,400, Zaporizhzhya Oblast – 2,300, Vinnytsya Oblast – 1,900, Poltava Oblast – 1,800, Zakarpattska Oblast – 1,500, Khmelnytskyi and Kyiv oblasts – 1,400, and Cherkasy Oblast has 1,300. This means that at least in these regions, each newly established povit will have at least 400–600 farms, and each community at least 50–100 of them. Such a development is especially likely if the local self-employed household farmers and entrepreneurs operating in adjacent branches of agribusiness find a common interest: their number in the communities will be at least 10-20 times higher than the number of farmers.