“You shouldn’t complain about having to obtain a Schengen visa until there is visa-free travel between Ukraine and the EU, but you have every right to complain about the conditions of this procedure”, a French colleague of mine once said, commenting on a story about people having to stand for several hours in a queue in freezing cold weather in front of the Embassy of the Czech Republic in Kyiv. He had never stood in a queue like this, and even refused to travel to Russia, simply because he had to apply for a visa to do so. This episode shows that there is quite a gap in perceptions of visa regulations between Ukraine and EU countries: the former is always a passive applicant and the latter act toughly without taking local circumstances into account.

The difficult and sometimes humiliating visa procedure discourages the most dynamic and European-minded segment of Ukrainian society – journalists, students, post-grad students, representatives of creative professions and public activists – from travelling and gaining experience that differs from post-Soviet realities. They must prove to representatives of embassies and consulates that they are not potential illegal migrants from a country viewed as being at the European bottom.

PRO FORMA REQUIREMENTS

Currently, there are four sources of law regulating the issuance of Schengen visas to Ukrainians: the agreement to simplify the visa procedure for Ukrainian nationals, the EU Visa Code, the Schengen Area law and the internal instructions of embassies and consulates. Two types of paperwork are required for Schengen visas: a common list of mandatory documents to confirm the purpose of travel (available on the websites of embassies and consulates) and a list of additional documents that prove the intent to return home. In effect, this paperwork guarantees that the applicant is safe to be admitted to the country he/she intends to visit and that he/she will return home. And this is where the fun begins – there are stories about the absurd and annoying things required of Ukrainians, such as the unexpected submission of documents that are completely bizarre or very difficult to obtain in the Ukrainian reality. Few are well-versed in the nuances of Schengen bureaucracy, but they are the key to understanding the problems faced by visa applicants in Ukraine.

READ ALSO: Eurostat: Russians – top EU asylum seekers

A simple and quick poll among those who have applied for Schengen visas has revealed that there are formalities which Ukrainians follow but which do not guarantee, prove or safeguard anything. However, they take time and could require additional expenses. A typical example is the requirement for a tourist to have a certain amount of money in a bank account during a trip. In this situation, Ukrainians usually use one of two schemes: they either put money onto a card account before applying for a visa then subsequently withdraw it once their documents have been examined, or borrow money from friends or relatives and return it once the operation has been completed. They don’t do this because they are tricksters or pathological fraudsters. First of all, Ukraine’s economy is a long way from having the same extent of private payments transferred through banks as in EU countries. Secondly, the official income of a person in Ukraine is one-tenth of the average in the EU. So Ukrainians are forced to embellish the reality in the eyes of consular employees for a week or two – for as long as it takes to meet formal Schengen requirements – then restore the unvarnished version.

Another telling example is the requirement for people working in the mass media who are applying for a multiple-entry Schengen visa to be members of the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine. Following this reasoning, authors would have to prove their membership in the Union of Writers of Ukraine and film directors in the Union of Filmmakers. At present, the Union of Journalists is a Soviet legacy rather than an organization defending journalists’ rights. However, journalists are forced to join it – regardless of the existence of motivation and desire to become involved in its activities – in order to obtain a visa and be able to go abroad on assignments. A number of journalists admitted to The Ukrainian Week that they had joined the union and paid its membership fees for the express purpose of obtaining a Schengen visa. Curiously, the German Embassy once denied a multi-entry visa to Yuriy Lukanov who was, at the time, the head of the Independent Kyiv Media Trade Union. He was going to go to Germany with a delegation from his organization to exchange experience and had an invitation from the government. He had travelled to Germany many times on a multi-entry Schengen visa prior to this. Lukanov was finally granted a visa for several months, in view of the fact that he was to shoot a film in Slovakia after his trip to Germany.

READ ALSO: Edward Hugh: young population exodus from Ukraine can be lethal for the country

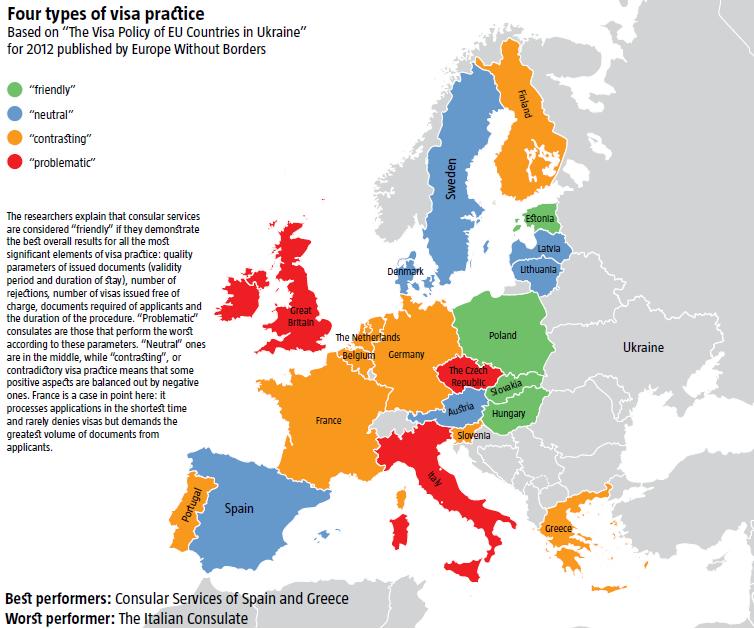

Some European embassies and consulates demand 4-6 additional documents and others demand 8-16. The officials of some states are prepared to take special Ukrainian circumstances such as unofficial salaries into account. Other bureaucrats, however, prefer not to notice the reality and stick to formal criteria and demands that only reflect the realities of their own countries. According to the estimates of the Europe Without Borders NGO, the consulates of neighbouring countries (Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) tend to have a better understanding and meet Ukrainians halfway. Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, the Czech Republic and Great Britain (a country outside the Schengen Area) are more formalistic (see Four types of visa practice).

For Ukrainians, one of the cruellest bureaucratic tactics is the requirement to present a statement issued by a tax administration body proving the applicant’s income indicated in a statement issued by his/her employer. For example, the German Embassy demanded this fiscal document from a Lviv-based journalist who was going to Germany to report on a boxing match. In other words, a situation is being created, whereby Ukrainians do not receive exclusive information from abroad, because representatives of their mass media may be denied entry for formal reasons which they cannot influence directly. The same statement may be demanded by the German Embassy from parents who want to visit their children studying or temporarily residing in Germany on an internship. Considering the employment circumstances of many Ukrainians today, this kind of “additional” requirement may put an end to their Schengen visa application. Why are Ukrainians, who work honestly at their place of employment and comply with every law that can realistically be complied with in Ukrainian realities, being stripped of the right to visit their children? This is a question that would sound absurd to Italians, the French, the British, Poles and Slovaks.

The Ukrainian Week has already written about an absurd case that took place in the Czech Embassy: a Ukrainian entrepreneur had a legal business in the Czech Republic and decided to send his 17-year-old daughter to study there. Even though he met all the requirements and had made an advance payment of more than EUR 6,000 to Charles University, she was denied a student visa under the pretext that she had demonstrated a poor knowledge of Czech realities during her interview. “A person who has experience in dealing with the consulate would have turned for help to a Tamara, Natasha or Nastia, women who loiter near the Embassy premises, asking EUR 500-700 for a visa – a miracle would have happened and the girl would have been granted the right to enter the country,” Jan Čech, a contributor to The Ukrainian Week, wrote with irony in one of his articles. Indeed, such people loiter near just about every embassy. They offer assistance in obtaining visas or, in the case of a rejection, the cherished “permit” to enter the Schengen Area, charging steep fees for their services. Their presence does not reflect well on consular and embassy employees, who often set unreasonable requirements for Ukrainians.

READ ALSO: Most legal immigrants to EU countries are from Ukraine

The latter include somewhat exotic requirements, such as notarized confirmation by the husband that he will be paying for his wife, even if they are travelling together and that they are officially married. The grounds for this requirement – to prove that both will be using the husband’s account. The Ukrainian Week knows of a similar case with the Dutch Embassy, which had such a requirement. What it means is that a Ukrainian citizen must confirm that not only he but also his wife will be using his money. However, isn’t it logical that a family has a common budget? A formal precondition for such requirements may be the fact that the applicants have no prior Schengen visas or have a new foreign passport which doesn’t have Schengen visas in it.

“Consulates prompt people to obtain separate documents. If something does not match reality, Ukrainians are accused of sins”, comments Iryna Sushko, leader of Europe Without Borders. “There is no point in demanding documents that cannot guarantee security and the intent to leave EU member-states. For example, tourists are sometimes asked to confirm not only hotel room booking but also tour programmes and programmes for their stay. This is not a document that guarantees the applicant’s security or helps a consul to judge whether such person could potentially remain on EU territory.”

BORDER SURPRISES

In addition to the two lists of documents – one to confirm the purpose of travel and the other the intent to return – there are two more stages of the Schengen visa procedure. The person undergoes the first one within the walls of the EU member-state embassy or consulate, the second is at the border crossing, a stage at which “surprises” can emerge.

A post graduate student from the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine had a Schengen visa in his passport and was on his way to visit his girlfriend, a student in Hungary. He boarded an electric train in Chop. Hungarian border guards demanded to see a document confirming that he had a place to live in Hungary. Delay, stress, threats of deportation and urgent requests to Kyiv to arrange for another invitation was the resulting scenario. Smugglers can successfully avoid these headaches, as can be seen on the Ukrainian-Polish border. “Nowhere did it say that I had to have a notarized copy or original of a document confirming my place of stay in Hungary when crossing the border. This check was performed selectively,” the young man told The Ukrainian Week. “I call it social discrimination: if you travel by plane, you are a prestigious person, but passengers on an electric train are looked at completely differently.” Hungarian border guards may not know that PhD students in EU countries also use cheaper means of transportation and that the target groups for checks (professional profiteers and small-scale smugglers) have other age and social parameters than PhD students from the National Academy of Sciences. Of course, the young man submitted all the necessary documents with his visa application, but he had no idea about what could happen at the border. Therefore, at the very least, Ukrainians must be properly informed, even at the first stage of the visa procedure, that they have to carry all invitations and confirmations of where they will be staying and bookings on their person at all times.

READ ALSO: The US Bans Visa for Prosecutor General

Dmytro, a student, experienced a similar situation but with a sad end – he was deported from the EU. The Polish Consulate issued him a multi-entry visa (category C) valid for 90 days, to visit his godfather. The young man and his father visited his godfather, then left for Spain for a vacation one day later. “When we crossed the German border, we were stopped and our papers were checked. That’s when everything started,” Dmytro says about his “adventures” near Görlitz. “They asked us where we were going and for what purpose. At one point, I showed them my course paper from my notebook to prove that I am a student at the University of Culture rather than someone intending to become an illegal migrant worker.” The vacation in Spain was the main purpose of Dmytro’s travel, but he did not have a clue that a Schengen visa issued by a Polish Consulate would not allow him to make this trip: “In court, they explained that: “In our opinion, you are abusing a visa – you obtained a Polish visa to go to Spain. You should have spent at least 70-80 per cent of your time in Poland.”

WHAT CAN BE DONE

The bureaucratic jungle of visa regulations gives rise to a logical question: can a Ukrainian citizen refer to the Agreement on Simplifying Visa Procedures as a normative-legal act with direct effect and a source of law when he/she believes that his/her rights have been violated? According to experts, it all depends on the ability of the attorney to make a good case for the plaintiff. Moreover, challenging Schengen visa rejections can be unrealistic and inaccessible for Ukrainians. For example, in June 2010, the Italian Embassy denied a visa to Hanna Protasova, a post graduate student at the Kyiv Mohyla Academy. She wanted to attend the biennial Euroscience Open Forum, where speakers included Nobel Prize laureates. The formal reason for the rejection was “inaccurate information provided with regard to the purpose and conditions for staying in the country”. It is not known whether the employees of the Italian Consular Department checked their emails in those days, but a letter from EOF President Raymond Seltz himself, confirming the purpose of Protasova’s trip was of no avail. Embassy representatives, and later the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to which Protasova applied, stated that the only possible procedure to challenge the decision was by a lawsuit, filed in a court in Lazio, where her interests could only be represented by a certified Italian attorney.

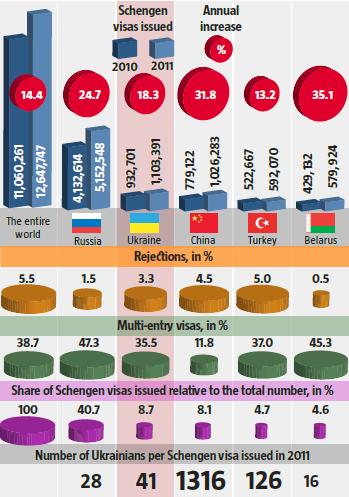

In its 2012 report, The Visa Policy of EU Countries in Ukraine, Europe Without Borders sums up as follows: “The atmosphere of political relations between the EU and third countries and the situation with democracy and human rights in these countries are a factor to which the EU is sensitive, but it has no significant impact on how liberal or strict visa policy is. This is clearly borne out by the positive dynamics in the number of visas issued by EU countries in Russia, Belarus and China.” The authors go on to say that the more liberal approaches of some EU countries to issuing visas in Russia and Belarus are “perceived as a manifestation of double standards” in Ukraine. They predict that in the next few years, “the liberalization/cancellation of visa regulations will continue to be an unpopular policy in EU countries. Therefore, the success of further efforts depends on systematic work with the target groups that shape public opinion in EU countries and have an impact on political decisions.” Thus, from now on, everything will depend on the willingness of those who could support the best intentions and aspirations of Ukrainian society to address visa issues.