The Verkhovna Rada passed the historic Law “On national security” in time for the July 2018 NATO Summit, where Ukraine hoped to be given its Membership Action Plan, 10 years after its original hopes were dashed. At the time, the law was referred to as a milestone of national security reform that would bring Ukraine closer to NATO. Passing the National Security Law was one of the key requirements of integration.

Drafting the bill took considerable time and effort, and had the support of NATO, EU and US experts. Still, Ukraine’s president was unable to attend the Summit as a full-fledged participant and report about the homework his country had completed because Hungary blocked the Ukrainian delegation over Ukraine’s new law on education. So Petro Poroshenko ended up visiting Brussels as a tourist. Despite productive meetings outside the Summit, the granting of the MAP was postponed indefinitely. The day will surely come, provided that the Ukrainian government completes everything it and promised its loyal partners and even included in the final provisions of the law on national security.

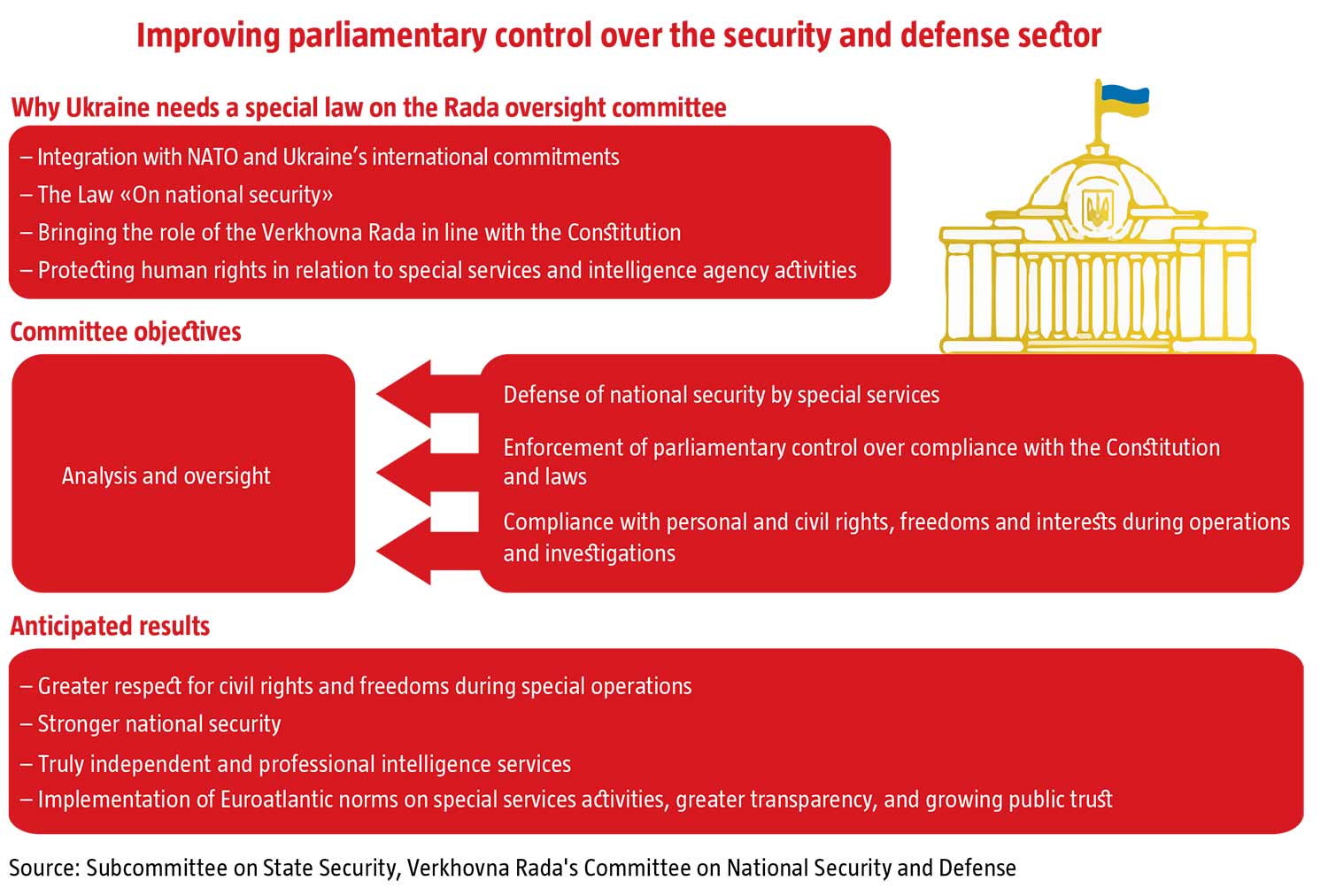

The fact is that, for the law to be implemented, the Rada needs to pass a few more bills. The Cabinet of Ministers has been given six months after this law comes into effect to draft a bill on the purpose and powers of the committee that will oversee the work of the country’s special services. The SBU, in that same timeframe, has to amend the law on the Security Bureau of Ukraine and submit it to the president who will present it to the Rada for review. Holos Ukrainy, the official Government bulletin, published the Law “On national security” on July 7, 2018, so January 8 marked end of the six-month period for preparing the bills needed for the national security law to be implemented.

According to The Ukrainian Week’s sources, neither the Cabinet nor the SBU drafted the bills by late December. Moreover, the SBU seemed suspicious about such a partnership initiative and attempted to cut it out even as the Rada was debating the national security law.

RELATED ARTICLE: NATO and Ukraine in 2019

Why the SBU dislikes the initiative is easy enough to understand. Right now, the Bureau is de factoneither accountable nor subject to oversight and faces minimal interference from officials, which makes its work a lot easier. In fact, requiring such an agency to operate transparently will simply reduce its effectiveness, especially given that Ukraine is currently at war. In fact, the SBU’s key arguments are about the war and the questionable reliability of any MPs who would exercise oversight. The Rada is full of agents, so how can they possibly be given access to state secrets? Who can guarantee that the oversight committee will be staffed with professionals who understand all the nuances of special services operations, and not a bunch of amateurs who will only use their position for self-promotion?

Still, the documents Ukraine promised will have to be passed. Firstly, a high level of secrecy for the country’s special services is not a major component of democratic values. For such agencies to preserve democracy successfully, they have to be politically neutral, unbiased and accountable, which means upholding professional ethics and working within the limits of the powers defined by law and the Constitution. Secondly, civilian and parliamentary oversight over security forces and all agencies in charge of policing and investigating is a top priority for Ukraine’s western partners, who believe that those with this kind of power need to be checked and an oversight committee will do that. This is one of the fundamental principles for NATO, whose members all have such a system and it works. Ukraine needs to also set up this kind of system if it wants to join this community.

To hope that its partners will close their eyes to this is pointless. The problem is not just the inevitable criticism, but about the possibility that Ukraine’s partners give up on the country. Since Ukraine does not have the MAP now means that NATO has no commitment to Ukraine. If Ukraine ignores one of NATO’s fundamental requirements, the Alliance will simply roll back cooperation to a minimum and no amount of diplomatic flourishes will make a difference. Besides, this is not what President Poroshenko needs if he wants to promote himself as a pro-Western candidate.

What’s more, these were not the only bills that had to be passed as part of the NATO deal. According to The Ukrainian Week’s sources, the bill on intelligence drafted by the foreign intelligence department and the Main Intelligence Directorate is ready, which is also needed in order to implement the security law. Western partners do have some qualms about it, but it has been drafted. Another important bill, #9122 on direct imports of weapons, finally passed first reading. It was not put on the agenda for a long time because MPs argued that it would be better to adopt it together with the defense procurement order so that here would be a better picture of the market situation. Only the procurement order was never completed while the chance to get far more military assistance from the US is too important to pass up.

Once the VR National Security and Defense Committee realized that the Cabinet was dragging its feet on drafting the new committee bill, it started the process on its own. According to Andriy Levus, chair of the state security subcommittee and one of the authors of the bill, the text of the bill on parliamentary oversight of special services compliance with laws is ready and had good feedback from the EU, US and NATO when the Ukrainian delegation presented it at the working group in Brussels December 14. All the stakeholders were invited to join the drafting process, which took several months. The drafters studied and adapted the practice of similar committees in NATO countries and took into account 90% of the recommendations of experts from the international advisory group. Ukraine’s intelligence agency was involved in the process as well. According to Levus, the authors were ready to hand the document over to the Government or President for submission to the Rada.

Despite the fears of the special services, the new committee should not cause them much moral or physical harm if it’s set up as prescribed. Aside from some burdens, it will also deliver some bonuses. The special services will effectively have their parliamentary body to carry out – in addition to oversight – all the functions that other committees handle: budgeting and legislating. It will review current laws, proposed legislation and international commitments. In a nutshell, it will facilitate the systemic reform and strengthening of the country’s special services – something they certainly need.

The bill contains a key measure to protect against traitors and fools in the committee: any MPs applying to the committee and its secretariat will have to get top security clearance. In addition, no official will be able to access active materials or databases on their own initiative. Access to such files will be granted or denied to a give group after the committee has been provided with a list of questions and a detailed list of documents being requested. If the committee denies access, it will have to explain its decision. Also, certain materials can be requested but without the right to disclose them. The procedural officer will have the power to decide whether MPs can see case files on national security operations, provided that they comply with the secrecy rules.

The bill also has a procedure for filing and reviewing complaints, as well as the option of inviting the leaders and participants of events to a committee meeting. The committee is to look at cases where there is evidence of crime in the actions of law enforcers that has been reported, especially in serious cases that require its intervention. Twice a year, the special services will have to report on how they have exercised their duties under law, and the committee will then report to the Rada on this. The committee is to submit a full report to the speaker, president and premier. Closed committee hearings must take place no less than twice a year to work on recommendations and proposals for removing any shortcomings that have been revealed. The committee also has to report to the public about its work at least twice a year.

RELATED ARTICLE: Where the compass points

Whether the bill from MPs and international experts is passed or not depends primarily on the position of the Presidential Administration. In theory, the Administration should be interested in getting the bill through. In practice, strengthening the role of the Rada means yet another headache. While the Constitution assigns oversight functions to the Verkhovna Rada, there is no toolkit for exercising it, nor can it oversee the executive branch that it itself forms. The Rada has even less power over the special services that are the president’s remit. Top officials are clearly happy with this set-up and would not want to change it, which means there could be efforts to dilute things by amending current laws, rather than writing a new bill, as Ukraine’s partners call for. The Cabinet of Ministers could toss in some last-minute amendments to expand the functions of the existing security committee and nothing more. The question is how Ukraine’s international partners will look at it.

Translated by Lidia Wolanskyj

Follow us at @OfficeWeek on Twitter and The Ukrainian Week on Facebook